Juvenile fish

Fish go through various life stages between fertilization and adulthood. The life of a fish start as spawned eggs which hatch into immotile larvae. These larval hatchlings are not yet capable of feeding themselves and carry a yolk sac which provides stored nutrition. Before the yolk sac completely disappears, the young fish must mature enough to be able to forage independently. When they have developed to the point where they are capable of feeding by themselves, the fish are called fry. When, in addition, they have developed scales and working fins, the transition to a juvenile fish is complete and it is called a fingerling, so called as they are typically about the size of human fingers. The juvenile stage lasts until the fish is fully grown, sexually mature and interacting with other adult fish.

Growth stages

Ichthyoplankton (planktonic or drifting fish) are the eggs and larvae of fish. They are usually found in the sunlit zone of the water column, less than 200 metres deep, sometimes called the epipelagic or photic zone. Ichthyoplankton are planktonic, meaning they cannot swim effectively under their own power, but must drift with ocean currents. Fish eggs cannot swim at all, and are unambiguously planktonic. Early stage larvae swim poorly, but later stage larvae swim better and cease to be planktonic as they grow into juveniles. Fish larvae are part of the zooplankton that eat smaller plankton, while fish eggs carry their own food supply. Both eggs and larvae are themselves eaten by larger animals.[1][2]

According to Kendall et al. 1984[2][3] there are three main developmental stages of fish:

- Egg stage: From spawning to hatching. This stage is named so, instead of being called an embryonic stage, because there are aspects, such as those to do with the egg envelope, that are not just embryonic aspects.

- Larval stage: From the eggs hatching till to when fin rays are present and the growth of protective scales has started (squamation). A key event is when the notochord associated with the tail fin on the ventral side of the spinal cord develops and becomes flexible. A transitional stage known as the sac larval stage, lasts from hatching to the complete resorption of the yolk sac.

- Juvenile stage: Starts when the morphological transformation or metamorphosis from larva to juvenile is complete, that is, when the larva develops the features of a functional fish. These features are that all the fin rays are present and that scale growth is under way. The stage completes when the juvenile becomes adult, that is, when it becomes sexually mature or starts interacting with other adults.

This article is about the larval and juvenile stage.

- Hatchling – refers to a recently hatched fish larva that is still too immature to achieve motility, and therefore not yet capable of active feeding. A hatchling still possesses a yolk sac upon which it depends for nutrition, and are thus also known as a sac fry.

- Fry – refers to a more developed hatchling whose yolk sac has almost disappeared, and its swim bladder is functional to the point where the fish can move around and perform limited foraging to nourish itself.[4] At this stage, the fish usually filter-feeds on planktons as it is still too small and slow to venture away from covers without being consumed by predators.

- Fingerling – refers to a fish that has reached the stage where the fins can be extended and protective scales have covered the body.[4] At this stage, the fish is typically about the size of a human finger,[5] hence the name. Once reaching this stage, the fish can be considered a juvenile, and is usually active enough to move around a large area. The feeding diet also changes from planktons to invertebrates and algae, occasionally other fish. The fish also starts to morphologically resemble adult fish gradually (though still smaller), although it is not yet achieved sexual maturity.

Juvenile salmon

Fry and fingerling are generic terms that can be applied to the juveniles of most fish species, but some groups of fishes have juvenile development stages particular to the group. This section details the stages and the particular names used for juvenile salmon.

- Sac fry or alevin – The life cycle of salmon begins and usually also ends in the backwaters of streams and rivers. These are their spawning grounds, where salmon eggs are deposited for among the gravels of stream beds. The salmon spawning grounds are also the salmon nurseries, providing a more protected environment than the ocean usually offers. After 2 to 6 months the eggs hatch into tiny salmon larvae called sac fry or alevin. These hatchlings have a yolk sac containing the remainder of the yolk and they stay hidden in the gravels for a few more days, as they are still largely immobile and rely on the remaining nutrients stored in the sac for survival.

- Fry – When the larvae develop further, their yolk sac gets depleted. Once the sac is almost completely gone the larvae must begin foraging for food by themselves, so they leave the protection of the gravel bed and start using their now-stronger tails to swim around feeding on plankton. At this point these mobile alevins become fries.

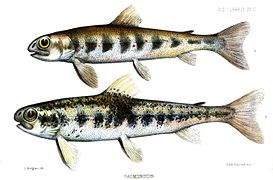

- Parr – When a fry has grown to roughly the size of a human finger, it develops protective scales and sufficiently strong fins, and is thus colloquially known as a fingerling. Fingerlings will start moving to a more carnivorous diet and quickly gain body mass, and at the end of the summer they develop into juvenile salmon called parr. Parr feed on small invertebrates and are camouflaged with a pattern of spots and vertical bars. They remain in this stage for up to three years.[6][7] Some older male parr are even already able to fertilize adult females' eggs in the spawning season, without having passed through the subsequent stages of development, and compete to do so with much larger anadromous adult males returning from the sea.[8]

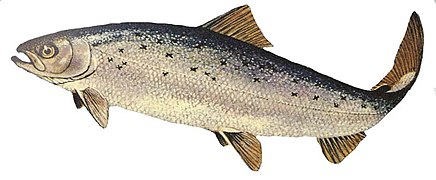

- Smolt – As they approach the time when they are ready to migrate out to the sea, the parr lose their camouflage bars and undergo a process of physiological changes that allows them to survive a shift from freshwater to saltwater environments. At this point these young salmon are called smolt. Smolt spend time in the brackish waters of the estuaries while their body chemistry adjusts (osmoregulation) to the higher salt levels they will encounter in the ocean.[9] Smolt also grow silvery scales with countershading, which visually confuse ocean predators.

- Post-smolt – When they have matured sufficiently in late spring and are about 15 to 20 centimetres long, the smolt swim out of the rivers and into the sea. There they spend their first year as post-smolt. Post-smolt form schools with other post-smolt and set off to find deep-sea feeding grounds. They then spend up to four more years as adult ocean salmon while their full swimming and reproductive capacity develops.[6][7][9]

-

Salmon eggs. The growing larvae can be seen through the transparent egg envelope. The black spots are the eyes.

-

Salmon egg hatching into a sac fry. In a few days, the sac fry will absorb the yolk sac and become a salmon fry

-

Sac fry remain in the gravel habitat of their redd (nest) while their yolk sac, or "lunch box" is depleted (click to enlarge)

-

The juvenile salmon, parr, grow up in the relatively protected natal river

-

The parr lose their camouflage bars and become smolt as they become ready for the transition to the ocean

-

Salmon enter the ocean as post-smolt and mature into adult salmon. They gain most of their weight in the ocean

Protection from predators

Juvenile fish need protection from predators. Juvenile species, as with small species in general, can achieve some safety in numbers by schooling together.[10] Juvenile coastal fish are drawn to turbid shallow waters and to mangrove structures, where they have better protection from predators.[11][12] As the fish grow, their foraging ability increases and their vulnerability to predators decreases, and they tend to shift from mangroves to mudflats.[13] In the open sea juvenile species often aggregate around floating objects such as jellyfish and Sargassum seaweed. This can significantly increase their survival rates.[14][15]

As human food

Juvenile fish are marketed as food.

- Whitebait is a marketing term for the fry of fish, typically between 25 and 50 millimetres long. Such juvenile fish often travel together in schools along the coast, and move into estuaries and sometimes up rivers where they can be easily caught with fine meshed fishing nets. Whitebaiting is the activity of catching whitebait. Whitebait are tender and edible, and can be regarded as a delicacy. The entire fish is eaten including head, fins and gut. Some species make better eating than others, and the particular species that are marketed as "whitebait" varies in different parts of the world. As whitebait consists of fry of many important food species (such as herring, sprat, sardines, mackerel, bass and many others) it is not an ecologically viable foodstuff and in several countries strict controls on harvesting exist.

- Elvers are young eels. Traditionally, fishermen consumed elvers as a cheap dish, but environmental changes have greatly reduced eel populations and the European eel is now critically endangered.[16] Glass eels are even younger eels than elvers, the stage in the Eel life history when eels first arrive in rivers and swim upstream from the sea in which they hatched. Because the eel cannot be farmed, eels have instead been caught from the wild as juveniles and reared in captivity for human consumption, reducing the wild population further.[17] Like whitebait, elvers are now considered a delicacy and are priced at up to 1000 euro per kilogram. A small serving of Spanish angulas, (literally: 'eels') for example, can cost the equivalent of US$100, and other species which can be purchased cheaply are prepared and eaten as "angulas" instead.[18][19] Glass eels are regularly smuggled out of Europe having been harvested illegally for Asian and Russian consumers; smugglers can earn millions of pounds sterling.[20][21][22] Elvers reach a higher price in China than does beluga caviar.[23] The Marine Conservation Society advises against buying European eels.[17]

See also

- Fish development

- LarvalBase – global online database on fish eggs and juvenile fish

- Spawning

Notes

- ^ What are Ichthyoplankton? Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA. Modified 3 September 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ a b Moser HG and Watson W (2006) "Ichthyoplankton" Pages 269–319. In: Allen LG, Pondella DJ and Horn MH, Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24653-9.

- ^ Kendall Jr AW, Ahlstrom EH and Moser HG (1984) "Early life history stages of fishes and their characters"[permanent dead link] American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Special publication 1: 11–22.

- ^ a b Guo Z, Xie Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhang D and Sugiyama S (2008) Review of fishery information and data collection systems in China[permanent dead link] Page 38. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture, Circular 1029. FAO, Rome. ISBN 978-92-5-105979-1.

- ^ fingerling Oxford dictionary. See: Origin. Accessed: 11 February 2020.

- ^ a b Bley 1988

- ^ a b Lindberg 2011

- ^ Jones, Matthew W.; Hutchings, Jeffrey A. (June 2001). "The influence of male parr body size and mate competition on fertilization success and effective population size in Atlantic salmon". Heredity. 86 (6): 675–684. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00880.x. ISSN 1365-2540. PMID 11595048.

- ^ a b Atlantic Salmon Trust 2011

- ^ Bone Q and Moore RH (2008) Biology of Fishes pp. 418–422, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-37562-7

- ^ Blaber SJM and Blaber TG (2006) "Factors affecting the distribution of juvenile estuarine and inshore fish" Journal of Fish Biology, 17 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1980.tb02749.x

- ^ Boehlert GW and Mundy BC (1988) "Roles of behavioral and physical factors in larval and juvenile fish recruitment to estuarine nursery areas" American Fisheries Society Symposium, 3 (5): 1–67.

- ^ Laegdsgaard P and Johnson C (2000) "Why do juvenile fish utilise mangrove habitats?" Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 257: 229–253.

- ^ Hunter, JR and Mitchell CT (1966) "Association of fishes with flotsam in the offshore waters of Central America". US Fishery Bulletin, 66: 13–29.

- ^ Kingsford MJ (1993) "Biotic and abiotic structure in the pelagic environment: Importance to small fishes" Bulletin of Marine Science, 53(2):393-415.

- ^ Jacoby, D. & Gollock, M. 2014. Anguilla anguilla . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T60344A45833138. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T60344A45833138.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/pdf/45833138

- ^ a b "European Eel - Anguilla anguilla | Marine Conservation Society". www.mcsuk.org. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Basque food: Angulas Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Randolph, Mike. "Why baby eels are one of Spain's most expensive foods". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "Illegal eel exporters exposed by Countryfile". 15 June 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Bryce, Emma (9 February 2016). "Illegal eel: black market continues to taint Europe's eel fishery". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Salesman smuggled £53m worth of live eels". BBC News. 6 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Gregory-Kumar, David (12 April 2017). "Illegal elvers worth more than caviar". BBC News. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

References

- Atlantic Salmon Trust Salmon Facts Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Bley, Patrick W and Moring, John R (1988) Freshwater and Ocean Survival of Atlantic Salmon and Steelhead: A Synopsis" US Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Lindberg, Dan-Erik (2011) Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) migration behavior and preferences in smolts, spawners and kelts Introductory Research Essay, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.