82nd Airborne Division

| 82nd Division 82nd Infantry Division 82nd Airborne Division | |

|---|---|

Insignia of the 82nd Airborne Division | |

| Active | 1917–1920, 1921–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Airborne light infantry |

| Role | Airborne assault |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Bragg, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Nickname(s) | "All American Division", "82nd Division", "Eighty Deuce", "America's Guard of Honor", "The 82nd" “Division” |

| Motto(s) | "All The Way!", "Death From Above" |

| Color of berets | Maroon |

| March | "The All-American Soldier" |

| Engagements | World War I

|

| Website | https://www.army.mil/82ndairborne |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | MG Christopher C. LaNeve |

| Deputy Commanding General – Operations | BG Brandon Tegtmeier |

| Deputy Commander – Support | COL Shane Morgan |

| Deputy Commander – Plans | Brigadier Neil Den-McKay, British Army |

| Chief of Staff | COL Adam Cobb |

| Command Sergeant Major | CSM Randolph Delapena |

| Notable commanders | Complete list of commanders |

| Insignia | |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (subdued) |  |

| Combat service identification badge |  |

| Flag |  |

| Seal |  |

The 82nd Airborne Division is an airborne infantry division of the United States Army specializing in parachute assault operations into denied areas[1] with a U.S. Department of Defense requirement to "respond to crisis contingencies anywhere in the world within 18 hours".[2] Based at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the 82nd Airborne Division is part of the XVIII Airborne Corps. The 82nd Airborne Division is the U.S. Army's most strategically mobile division.[3]

The division was constituted, originally as the 82nd Division, in the National Army on 5 August 1917, shortly after the American entry into World War I. It was organized on 25 August 1917, at Camp Gordon, Georgia and later served with distinction on the Western Front in the final months of World War I. Since its initial members came from all 48 states, the division acquired the nickname All-American, which is the basis for its "AA" on the shoulder patch. The division later served in World War II where, in August 1942, it was reconstituted as the first airborne division of the U.S. Army and fought in numerous campaigns during the war.

Origins

The 82nd Division was first constituted during World War I on 5 August 1917 as an infantry division in the National Army. It was organized and formally activated on 25 August 1917 at Camp Gordon, Georgia.[4] The division consisted entirely of newly conscripted soldiers.[5] The original enlisted men assigned to the division came from Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee, but during October 1917, a large number were transferred to fill shortages in Regular Army and National Guard units preparing to move overseas, and replacements for them were received mostly from New England and the Mid-Atlantic states.[6][7] The citizens of Atlanta held a contest to give a nickname to the new division, and in April 1918, Major General Eben Swift, the commanding general, chose "All American" to reflect the unique composition of the 82nd—it had soldiers from all 48 states.[8] The bulk of the division was two infantry brigades, each commanding two regiments. The 163rd Brigade commanded the 325th Infantry Regiment and the 326th Infantry Regiment along with the 320th Machine Gun Battalion. The 164th Brigade commanded the 327th Infantry Regiment and the 328th Infantry Regiment and the 321st Machine Gun Battalion.[9] Also in the division were the 157th Field Artillery Brigade, composed of the 319th, 320th and 321st Field Artillery Regiments and the 307th Trench Mortar Battery; a divisional troops contingent, and a division train. The division sailed to Europe in May 1918 to join the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), commanded by General John Pershing, on the Western Front.[10]

World War I

Brigadier General William P. Burnham, who had previously commanded the 164th Brigade, led the division during most of its training and its movement to Europe. In early April 1918, the division embarked from the ports in Boston, New York and Brooklyn to Liverpool, England, where the division fully assembled by mid-May 1918.[11] From there, the division moved to Continental Europe, leaving Southampton and arriving at Le Havre, France,[11] and then moved to the British-held region of Somme on the front lines, where it began sending small numbers of troops and officers to the front lines to gain combat experience. On 16 June it moved by rail to Toul, France to take a position on the front lines in the French sector. Its soldiers were issued French weapons and equipment to simplify resupply.[5] The division was briefly assigned to I Corps before falling under the command of IV Corps until late August. It was then moved to the Woëvre front, in the Lagney sector, where it operated with the French 154th Infantry Division.[11]

St. Mihiel

The division relieved the 26th Division on 25 June. Though Lagney was considered a defensive sector, the 82nd Division actively patrolled and raided in the region for several weeks, before being relieved by the 89th Division.[5] From there it moved to the Marbache sector in mid-August, where it relieved the 2nd Division under the command of the newly formed US First Army.[11] There it trained until 12 September, when the division joined the St. Mihiel offensive.[5]

Once the First Army jumped off on the offensive, the 82nd Division engaged in a holding mission to prevent Imperial German Army forces from attacking the right flank of the First Army. On 13 September, the 163rd Brigade and 327th Infantry Regiment raided and patrolled to the northeast of Port-sur-Seille, toward Eply, in the Bois de Cheminot, Bois de la Voivrotte, Bois de la Tête-d'Or, and Bois Fréhaut. Meanwhile, the 328th Infantry Regiment, in connection with the attack of the 90th Division against the Bois-le-Prêtre, advanced on the west of the Moselle River, and, in contact with the 90th Division, entered Norroy, advancing to the heights just north of that town where it consolidated its position. On 15 September, the 328th Infantry, in order to protect the 90th Division's flank, resumed the advance, and reached Vandières, but withdrew on the following day to the high ground north of Norroy.[11]

On 17 September, the St-Mihiel Operation stabilized, and the 90th Division relieved the 82nd's troops west of the Moselle River. On 20 September, the 82nd was relieved by the French 69th Infantry Division, and moved to the vicinity of Marbache and Belleville, then to stations near Triaucourt and Rarécourt in the area of the First Army.[11] During this operation, the division suffered heavy casualties from enemy artillery. The operation cost the division over 800 men. Among them was Colonel Emory Jenison Pike of the 321st Machine Gun Battalion, the first member of the 82nd to be awarded the Medal of Honor.[5] The division was then moved into reserve until 3 October, when it assembled near Varennes-en-Argonne prior to returning to the line.[11] During this time, the division trained and prepared for the war's final major offensive at Meuse-Argonne.[5]

Meuse-Argonne

The division was next moved to the Clermont area, located west of Verdun on 24 September. They were stationed there to act as a reserve for the US First Army.[12] On 3 October there was a change in command of the division as Major General George B. Duncan, former commander of the 77th Division, relieved Burnham. Burnham, who had been with the division since its activation, subsequently served as military attaché in Athens, Greece. On the night of 6/7 October 1918, the 164th Brigade relieved troops of the 28th Division, which were holding the front line from south of Fléville to La Forge, along the eastern bank of the Aire River. The 163rd Brigade remained in reserve. On 7 October the division, minus the 163rd Brigade, attacked the northeastern edge of the Argonne Forest, making some progress toward Cornay, and occupied Hill 180 and Hill 223. The next day it resumed the attack. Elements of the division's right flank entered Cornay but later withdrew to the east and south. The division's left flank reached the southeastern slope of the high ground northwest of Châtel-Chéhéry. On 9 October, the division continued its attack, and advanced its left flank to a line from south of Pylône to the Rau de la Louvière.[11]

For the rest of the month, the division turned to the north and advanced astride the Aire River to the region east of St-Juvin. On 10 October, it relieved troops of 1st Division on the right, north of Fléville, as far as a new boundary extending north and south through Sommerance. It then attacked and captured Cornay and Marcq, and established the front just to their south. On 11 October, the right flank of the division occupied Sommerance and the high ground north of la Rance Rau while the left advanced to the railroad south of the Aire. The next day, the 42nd Division relieved the 82nd's troops in and near Sommerance, allowing it to resume the attack. The 82nd passed through part of the Hindenburg defensive position and reached a line just north of the road from St-Georges to St-Juvin.[11]

On 18 October, the division relieved elements of the 78th as far to the left as Marcq and Champigneulle. Three days later it advanced to the Ravin aux Pierres. On 31 October, the 82nd, except the artillery, was relieved by the 77th Division and the 80th Division, and assembled in the Argonne Forest near Champ-Mahaut. On 2 November, the division concentrated near La Chalade and Les Islettes, and, on 4 November, moved to training areas in Vaucouleurs. On 10 November, it moved again to training areas in Bourmont, where it remained until the Armistice of 11 November 1918.[11] During this campaign the division suffered another 7,000 killed and wounded. A second 82nd soldier, Alvin York, received the Medal of Honor for his actions during this campaign,[5] which involved rushing a German machine gun nest capturing over a hundred German soldiers and killing 23 soldiers.

Post-war

The division suffered 995 killed and 7,082 wounded, for a total of 8,077 casualties.[13] Following the war's end, the division moved to training areas near Prauthoy, where it remained through February 1919.[11] It returned to the United States in April and May, and was demobilized and deactivated at Camp Mills, New York, on 27 May.[4]

Interwar period

For the next two years, the 82nd Division existed as a unit of the Organized Reserve.[14] It was reconstituted on 24 June 1921 establishing headquarters at Columbia, South Carolina, in January 1922. Elements of the division were located in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.[5]

World War II

Initial training and conversion

The 82nd Division was redesignated on 13 February 1942 during World War II, just two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the German declaration of war, as Division Headquarters, 82nd Division. It was ordered into active service on 25 March 1942, and reorganized at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, under the command of Major General Omar Bradley. During this training period, the division brought together three officers who would ultimately steer the U.S. Army during the following two decades: Matthew Ridgway, James M. Gavin, and Maxwell D. Taylor.[15] Under Major General Bradley, the 82nd Division's Chief of Staff was George Van Pope.[16]

On 15 August 1942, the 82nd Infantry Division, now commanded by Major General Ridgway, became the first airborne division in the history of the U.S. Army, and was redesignated as the 82nd Airborne Division. The 82nd was selected after deliberations by the U.S. Army General Staff because of a number of factors; it was not a Regular Army or National Guard unit ("many traditionalists in those components wanted nothing to do with such an experimental force"), its personnel had all completed basic training, and it was stationed in an area that had good weather and flying facilities.[17] The division initially consisted of the 325th, 326th and 327th Infantry Regiments, and supporting units. The 327th was soon transferred to help form the 101st Airborne Division and was replaced by the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, leaving the division with two regiments of glider infantry and one of parachute infantry. In February 1943 the division received another change when the 326th was transferred to the 13th Airborne Division, being replaced by the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, under James M. Gavin, then a colonel, who was later to command the division.

Sicily and Italy

In April 1943, after several months of tough training, its troopers deployed to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, under the command of Major General Ridgway to take part in the campaign to invade Sicily. The division's first two combat operations were parachute assaults into Sicily on 9 July and Salerno on 13 September 1943. The initial assault on Sicily, by the 505th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, under Colonel Gavin, was the first regimental-sized combat parachute assault conducted by the United States Army. The first glider assault did not occur until Operation Neptune as part of the D-Day landings of 6 June 1944. Glider troopers of the 319th and 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalions and the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (and the 3rd Battalion of the 504th PIR) instead arrived in Italy by landing craft at Maiori (319th) and Salerno (320th, 325th).

In January 1944, the 504th, commanded by Colonel Reuben Tucker, which was temporarily detached to fight at Anzio, adopted the nickname "Devils in Baggy Pants", taken from an entry in a German officer's diary. The 504th was replaced in the division by the inexperienced 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel George V. Millet Jr. While the 504th was detached, the remainder of the 82nd Airborne Division moved to the United Kingdom in November 1943 to prepare for the liberation of Europe. See RAF North Witham and RAF Folkingham.

Normandy

With two combat drops under its belt, the 82nd Airborne Division was now ready for the most ambitious airborne operation of the war so far, as part of Operation Neptune, the Allied invasion of Normandy. The division conducted Mission Boston, part of the airborne assault phase of the Operation Overlord plan.

In preparation for the operation, the division was significantly reorganized. To ease the integration of replacement troops, rest, and refitting following the fighting in Italy, the 504th PIR did not rejoin the division for the invasion. Two new parachute infantry regiments (PIRs), the 507th and the 508th, provided it, along with the veteran 505th, a three-parachute infantry regiment punch. The 325th was also reinforced by the addition of the 3rd Battalion of the 401st GIR, bringing it up to a strength of three battalions.

On 5 and 6 June these paratroopers, parachute artillery elements, and the 319th and 320th, boarded hundreds of transport planes and gliders to begin history's largest airborne assault at the time (only Operation Market Garden later that year would be larger). During the 6 June assault, a 508th platoon leader, First Lieutenant Robert P. Mathias, would be the first U.S. Army officer killed by German fire on D-Day.[18] On 7 June, after this first wave of attack, the 325th GIR would arrive by glider to provide a division reserve.

In Normandy, the 82nd gained its first Medal of Honor of the war, belonging to Private First Class Charles N. DeGlopper of the 325th GIR.[19] By the time the division was relieved, in early July, the 82nd had seen 33 days of severe combat and casualties had been heavy. Losses included 5,245 troopers killed, wounded, or missing, for a total of 46% casualties. Major General Ridgway's post-battle report stated in part, "... 33 days of action without relief, without replacements. Every mission accomplished. No ground gained was ever relinquished."[14]

Following Normandy, the 82nd Airborne Division returned to England to rest and refit for future airborne operations. The 82nd became part of the newly organized XVIII Airborne Corps, which consisted of the 17th, 82nd, and 101st Airborne Divisions. Ridgway was given command of the corps but was not promoted to lieutenant general until 1945. His recommendation for succession as division commander was Brigadier General James M. Gavin, previously the 82nd's ADC. Ridgway's recommendation met with approval, and upon promotion Gavin became the youngest general since the Civil War to command a U.S. Army division.[20]

Market Garden

On 2 August 1944 the division became part of the First Allied Airborne Army. In September, the 82nd began planning for Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands. The operation called for three-plus airborne divisions to seize and hold key bridges and roads deep behind German lines. The 504th PIR, now back at full strength, was reassigned to the 82nd, while the 507th was assigned to the 17th Airborne Division, at the time training in England.

On 17 September, the "All American" Division conducted its fourth (and final) combat jump of World War II. Fighting off German counterattacks, the division captured its objectives between Grave, and Nijmegen. The division failed to capture Nijmegen Bridge when the opportunity presented itself early in the battle. When the British XXX Corps arrived in Nijmegen, six hours ahead of schedule, they found themselves having to fight to take a bridge that should have already been in allied hands. In the afternoon of Wednesday 20 September 1944, the 82nd Airborne Division successfully conducted an opposed assault crossing of the Waal river. War correspondent Bill Downs, who witnessed the assault, described it as "a single, isolated battle that ranks in magnificence and courage with Guam, Tarawa, Omaha Beach. A story that should be told to the blowing of bugles and the beating of drums for the men whose bravery made the capture of this crossing over the Waal possible."[21]

The Market Garden salient was held in a defensive operation for several weeks until the 82nd was relieved by Canadian troops, and sent into reserve in France. During the operation, 19-year-old Private John R. Towle of the 504th PIR was posthumously awarded the 82nd Airborne Division's second Medal of Honor of World War II.

The Bulge

On 16 December 1944, the Germans launched a surprise offensive through the Ardennes Forest, which became known as the Battle of the Bulge. In SHAEF reserve, the 82nd was committed on the northern face of the bulge near Elsenborn Ridge.

On 20 December 1944, the 82nd Airborne Division was assigned to take Cheneux which had been captured by Kampfgruppe Peiper. On 21–22 December 1944, the 82nd Airborne faced counterattacks from two Waffen SS divisions which included the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler and the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen. The Waffen SS efforts to relieve Kampfgruppe Peiper failed due to the stubborn defense of the 82nd Airborne, the 30th ID, 2nd ID, and other units.[22]

On 23 December, the Germans attacked from the south and overran the 325th GIR holding the Baraque- Fraiture crossroads on the 82nd's southern flank, endangering the entire 82nd Airborne division. The 2nd SS Panzers objective was to outflank the 82nd Airborne. It was not an attack designed to reach Peiper, but it was his last chance, nonetheless. If it did outflank the 82nd, it could have opened a corridor and reached the stranded yet still powerful Kampfgruppe. But the attack came too late.[citation needed]

On 24 December 1944, the 82nd Airborne Division with an official strength of 8,520 men was facing off against a vastly superior combined force of 43,000 men and over 1,200 armored fighting and artillery vehicles and pieces.[23] Due to these circumstances, the 82nd Airborne Division was forced to withdrawal for the first time in its combat history.[24] The Germans pursued their retreat with the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions. The 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich engaged the 82nd until 28 December when it and what was left of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte were ordered to move south to meet General George Patton's forces attacking in the area of Bastogne.[25] Some units of the 9th SS Panzer including the 19th Panzer Grenadier Regiment stayed and fought the 82nd. They were joined by the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division. The 9th SS Panzer tried to breakthrough by attacking the 508 and 504 PIR positions, but ultimately failed.[26] The failure of the 9th and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions to break through the 82nd lines marked the end of the German offensive in the northern shoulder of the Bulge. The German objective now became one of defense.

On 3 January 1945, the 82nd Airborne Division conducted a counterattack. On the first day's fighting the Division overran the 62nd Volksgrenadiers and the 9th SS Panzer's positions capturing 2,400 prisoners.[27] The 82nd Airborne suffered high casualties in the process. The attached 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion was all but destroyed during these attacks. Of the 826 men who went into the Ardennes, only 110 came out. Having lost its charismatic leader Lt. Colonel Joerg, and almost all its men either wounded, killed, or frostbitten, the 551 was never reconstituted. The few soldiers who remained were later absorbed into units of the 82nd Airborne.[28]

After several days of fighting, the destruction of the 62nd Volksgrenadiers, and what had been left of the 9th SS Panzer Division was complete. For the 82nd Airborne Division the first part of the Battle of the Bulge had ended.[29]

Into Germany

After helping to secure the Ruhr, the 82nd Airborne Division ended the war at Ludwigslust past the Elbe River, accepting the surrender of over 150,000 men of Lieutenant General Kurt von Tippelskirch's 21st Army on 2 May 1945. General Omar Bradley, commanding the U.S. 12th Army Group, stated in a 1975 interview with Gavin that Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, commanding the Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group, had told him that German opposition was too great to cross the Elbe. When Gavin's 82nd crossed the river, in company with the British 6th Airborne Division, the 82nd Airborne Division moved 36 miles in one day and captured over 100,000 troops, causing great laughter in Bradley's 12th Army Group headquarters.[30]

Following Germany's surrender, the 82nd Airborne Division entered Berlin for occupation duty, replacing the 2nd Armored Division in August 1945.[31]: 94 The division was relieved by the 78th Infantry Division early in November 1945.[31]: 131 In Berlin General George S. Patton was so impressed with the 82nd's honor guard he said, "In all my years in the Army and all the honor guards I have ever seen, the 82nd's honor guard is undoubtedly the best." Hence the "All-American" became also known as "America's Guard of Honor".[32] The war ended before their scheduled participation in the Allied invasion of Japan, Operation Downfall. During the invasion of Italy, Ridgway considered Will Lang Jr. of TIME magazine an honorary member of the division.

Composition

During WWII the division was composed of the following units:[33]

- 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (received the 2nd Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment 101st Airborne Division on 1 March 1945, which was reflagged 3rd Battalion 325th GIR)

- 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (assigned 15 August 1942; replaced 327th Infantry Regiment relieved that same date)

- 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (assigned 10 February 1943; replaced 326th Infantry Regiment which departed on 4 February 1943)

- 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion

- 80th Airborne Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion

- 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company (assigned 1 March 45)

- 307th Airborne Medical Company

- 82nd Airborne Division Artillery

- 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion (75 mm)

- 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm)

- 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (75 mm)

- 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (75 mm)

- Special Troops (Headquarters activated 1 Mar 45)

- Headquarters Company, 82nd Airborne Division

- 82nd Airborne Signal Company

- 407th Airborne Quartermaster Company

- 782nd Airborne Ordnance Company

- Reconnaissance Platoon (assigned 1 March 45)

- Military Police Platoon

- Band (assigned 1 March 45)

Attached paratrooper units:

- 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment (attached 14 June 1944 – 27 August 1944)

- 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment (attached 14 June 1944 – 21 June 1944; 23 January 1945 through 9 May 1945)

- 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment (attached 1–11 January 1945; 23–26 January 1945; 3–5 February 1945; 9–10 February 1945)

- 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion (attached 26 December 1944 – 13 January 1945; 21–27 January 1945)

Casualties

- Total battle casualties: 9,073[34]

- Killed in action: 1,619[34]

- Wounded in action: 6,560[34]

- Missing in action: 279[34]

- Prisoner of war: 615[34]

Awards

During World War II the division and its members were awarded the following awards:[35]

- Distinguished Unit Citations: 15

- Medal of Honor: 4

- Private John R. Towle(KIA)

- Private First Class Charles N. Deglopper(KIA)

- First Sergeant Leonard A. Funk Jr.

- Private Joe Gandara(KIA) (issued 18 March 2014)

- Distinguished Service Cross: 37

- Distinguished Service Medal: 2

- Silver Star: 898

- Legion of Merit: 29

- Soldier's Medal: 49

- Bronze Star Medal: 1,894

- Air Medal: 15

Cold War

Post–World War II

The division returned to the United States on 3 January 1946 on the RMS Queen Mary. The division initially was staged at Camp Shanks, New York, where they drilled for the coming Victory Parade. In New York City it led a big Victory Parade, 12 January 1946. In 1947 the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was assigned to the 82nd and was reflagged as the 3d Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (redesignated as the 505th Airborne Infantry Regiment effective 15 December 1947).[36] Instead of being demobilized, the 82nd found a permanent home at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, designated a Regular Army division on 15 November 1948. The 82nd was not sent to the Korean War, as both Presidents Truman and Eisenhower chose to keep it in strategic reserve in the event of a Soviet ground attack anywhere in the world. Life in the 82nd during the 1950s and 1960s consisted of intensive training exercises in all environments and locations, including Panama, the Far East, and the continental United States.

Pentomic organization

In 1957, the division implemented the pentomic organization (officially Reorganization of the Airborne Division (ROTAD)) in order to better prepare for tactical nuclear war in Europe. Five battle groups (each with a headquarters and service company, five rifle companies and a mortar battery) replaced the division's three regiments of three battalions each. The division's battle groups were:[37]

- 1st Airborne Battle Group (ABG), 187th Infantry (reassigned from the 24th Infantry Division on 8 February 1959)(1)[38]

- 1st ABG, 325th Infantry

- 2nd ABG, 501st Infantry

- 1st ABG, 503d Infantry (reassigned from the 24th Infantry Division on 1 July 1958)(2)[39]

- 2nd ABG, 503rd Infantry (reassigned to the 25th Infantry Division on 24 June 1960)[39]

- 1st ABG, 504th Infantry (reassigned to the 8th Infantry Division on 11 December 1958)[40]

- 2nd ABG, 504th Infantry (assigned effective 9 May 1960)(1)[41]

- 1st ABG, 505th Infantry (reassigned to the 8th Infantry Division on 15 January 1959)[42]

- (1) 1st ABG, 504th Infantry and 1st ABG, 505th Infantry were reassigned to the 8th Infantry Division in central West Germany to provide airborne capability in Germany; in turn, 1–187th and 1-503d were reassigned from the 24th Infantry Division in southern Germany to the 82nd Airborne Division

- (2) 2nd ABG, 503rd Infantry was reassigned to the 25th Infantry Division and stationed in Okinawa to provide airborne capability in the Pacific on 24 June 1960. This ABG was reassigned to the 173d Airborne Brigade on 26 March 1963.[39]

- the Division Artillery consisted of:

- Battery A, 319th Artillery

- Battery B, 319th Artillery

- Battery C, 319th Artillery (Battery C, 320th Artillery after 1960; C-319th accompanied the 2d ABG, 503d Infantry on its assignment to the 25th Infantry Division)[43]

- Battery D, 320th Artillery

- Battery E, 320th Artillery

- Battery B, 377th Artillery

- additional division elements consisted of:

- 82nd Medical Company

- 82nd Signal Battalion

- 82nd Aviation Company

- Troop A, 17th Cavalry

- 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion

- 407th Supply and Transportation Battalion (The 82nd Quartermaster Parachute Supply and Maintenance Company [activated 1 March 1945] was reorganized and redesignated as Company B, 407th S&T Battalion.)[44]

- 782nd Maintenance Battalion

The pentomic organization was unsuccessful, and the division reorganized into three brigades of three battalions (the Reorganization Objective Army Division (ROAD) organization) in 1964.

Dominican Republic and Vietnam deployments

In April 1965, the "All-Americans" entered the civil war in the Dominican Republic. Spearheaded by the 3rd Brigade, the 82nd deployed in Operation Power Pack.

During the Tet Offensive, which swept across South Vietnam in January/February 1968, the 3rd Brigade was en route to Chu Lai within 24 hours of receiving its orders. The 3rd Brigade performed combat duties in the Huế – Phu Bai area of the I Corps sector. Later the brigade moved south to Saigon, and fought in the Mekong Delta, the Iron Triangle and along the Cambodian border, serving nearly 22 months. While the 3rd Brigade was deployed, the division created a provisional 4th Brigade, consisting of 4th Battalion, 325th Infantry; 3d Battalion, 504th Infantry; and 3d Battalion, 505th Infantry. An additional unit, the 3d Battalion, 320th Artillery, was activated under Division Artillery to support the 4th Brigade.

The units assigned and attached to the 3d Brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division were as follows:[45]

- Brigade Infantry:

- 1st Battalion (Airborne), 505th Infantry

- 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 505th Infantry

- 1st Battalion (Airborne), 508th Infantry

- Brigade Artillery:

- 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 321st Artillery (105mm)

- Brigade Aviation:

- Company A, 82nd Aviation Battalion

- Brigade Reconnaissance:

- Troop B, 1st Squadron (Armored), 17th Cavalry

- Company O (Ranger), 75th Infantry

- Brigade Support:

- 82nd Support Battalion

- 58th Signal Company

- Company C, 307th Engineer Battalion (Airborne)

- 408th Army Security Agency Detachment

- 52nd Chemical Detachment

- 518th Military Intelligence Detachment

- 307th Medical (Airborne) Headquarters and Alpha Company

The deployment of the 3rd Brigade took place with significant problems and controversy. In The Rise and Fall of an American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam, 1965–1973, author Shelby L. Stanton describes how, other than the 82nd, only two under-strength Marine and four skeletonized Army divisions were left stateside by the beginning of 1968. MACV, desperate for additional manpower, wanted the division to deploy to Vietnam, and the Department of the Army, wishing to retain its "sole readily deployable strategic reserve, the last real vestige of actual Army divisional combat potency in the United States left to the Pentagon," compromised by sending the 3d Brigade. As Stanton wrote:

The division had been so rushed to get this brigade to the battlefront that it ignored individual deployment criteria. Paratroopers who had just returned from Vietnam now found themselves suddenly going back. The howl of soldier complaints was so vehement that the Department of the Army was soon forced to give each trooper who had deployed to Vietnam with the 3d Brigade the option of returning to Fort Bragg or remaining with the unit. To compensate for the abrupt departures from home for those who elected to stay with the unit, the Army authorized a month leave at the soldiers' own expense or a two-week leave with government aircraft provided for special flights back to North Carolina. Of the 3,650 paratroopers who had deployed from Fort Bragg, 2,513 elected to return to the United States at once. MACV had no paratroopers to replace them, and overnight the brigade was transformed into a separate light infantry brigade, airborne in name only.

Urban riots in 1967–68

1967 Detroit Riot

On 24 July 1967, shortly before midnight, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered the U.S. military into Detroit to boost the Detroit Police Department, the Michigan State Police, the Wayne County Sheriff, and the Michigan Army National Guard in curtailing the city's ongoing major civil disorder.[46] At 1:10 am, 4,700 paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, under the command of Lieutenant General John L. Throckmorton, arrived in Detroit[47] and began working in the streets, coordinating refuse removal, tracing persons who had disappeared in the confusion, and carrying out routine military functions, such as the establishment of mobile patrols, guard posts, and roadblocks.[48]

Later that night, rioting peaked in high intensity, and the 82nd worked alongside the 101st to secure east of Woodward, while the National Guard took to the west of Woodward. Incidents began to decline, as the paratroopers constantly patrolled the perimeter with M16 rifles, M60 machine guns, and M48 tanks, and the police began making arrests on those violating curfew regulations or who were caught looting. On 27 July, with a sense of normalcy returned to the city, in part due to the presence of Army and National Guard troops, the riot was officially declared over. The Army began to scale down in order to return to their normal duties, leaving the control back to local authorities.[49]

Although Army paratroopers exercised great restraint on firepower due to being racially integrated as well as their combat experience in Vietnam (as opposed to the mainly white and inexperienced National Guard troops), the 82nd was responsible for one death and the only riot fatality associated with federal troops. On 29 July, two days after the riot officially ended, 82nd Captain Randolph Smith fatally shot a 19-year-old black man, Ernest Roquemore,[50] who inadvertently strayed into the line of fire east of the alley, as the paratroopers and the police were firing at a man allegedly armed with a gun (it was later found out to be a transistor radio). Three other individuals were injured by shotgun fire from police in the same incident. The Army and Detroit Police were on a joint patrol in order to recover looted items within the vicinity where the shooting took place.[51]

On 30 July, the 82nd and the 101st completely left Detroit and moved back to Selfridge for redeployment to their home stations, a process that continued gradually until 2 August.[48]

1968 riots in Washington, D.C. and Baltimore

The 82nd was called in to tackle civil disturbances in Washington, D.C. and Baltimore in the wake of the nationwide riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on 4 April 1968. In Washington, D.C., the first of 21 aircraft carrying the 1st Brigade Combat Team of the 82nd landed at Andrews Air Force Base on 6 April, with the 82nd's 2nd Brigade Combat Team joining up later.[52] In total, more than 2,000 82nd paratroopers were among the 11,850 federal troops to assist the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia and the D.C. Army National Guard in Washington. By then, the rioting had largely ended, but isolated looting and arson continued for a few more days. On 8 April, when D.C. was considered pacified, the 1st Brigade was later moved to Baltimore in assisting the Maryland National Guard and the Baltimore Police Department because of the ongoing city's disorder there, leaving the 2nd Brigade the only 82nd unit in Washington.[52]

The 82nd brigades in D.C. and Baltimore worked with other federal, state, and local forces in maintaining order, detaining looters, clearing any signs of trouble, assisting crews clearing debris from the main traffic arteries, and helping sanitation, food store, and public utility employees to restore essential services within devastated areas.[53] On 12 April, orders were issued for federal troops and National Guardsmen stationed in both cities to return to their home stations. The 1st Brigade was among the federal forces that left Baltimore by midnight the same day and three days later, the 2nd Brigade went into an assembly area at Bolling Air Force Base, where they eventually departed back to Fort Bragg sometime later.[54]

Post-Vietnam Operations

From 1969 into the 1970s, the 82nd deployed paratroopers to South Korea and Vietnam on more than 180DBT (Days Bad Time) for exercises in potential future battlegrounds. The division received three alerts. One was for Black September 1970. Paratroopers were on their way to Amman, Jordan when the mission was aborted. In May 1971 they were used to help national guard and Washington DC police to round up and arrest protestors.[55][56] Nine years later in August 1980, the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 504th Infantry was alerted and deployed to conduct civil disturbance duty at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, during the Cuban refugee internment. War in the Middle East in the fall of 1973 brought the 82nd to full alert. President Gerald Ford put the unit on high alert in case the administration decided to intervene in the Boston desegregation busing crisis.[57] In May 1978, the division was alerted to a possible drop into Zaire. In November 1979, the division was alerted for a possible operation to rescue the American hostages in Iran. The division formed the nucleus of the newly created Rapid Deployment Forces (RDF), a mobile force at a permanently high state of readiness.[citation needed]

Invasion of Grenada – Operation Urgent Fury

On 25 October 1983, elements of the 82nd conducted an Airland Operation to secure Point Salines Airport following an airborne assault by the 1st and 2nd Ranger Battalions who conducted the airfield seizure just hours prior. The first 82nd unit to deploy was a task force of the 2d and 3d Battalions (Airborne), 325th Infantry. On 26 October and 27, the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 505th Infantry, and the 1st and 2nd Battalions (Airborne), 508th Infantry, deployed to Grenada with support units. 2-505 deployed as well. Military operations ended in early November (Note: that C/2-325 did not deploy due to being a newly formed COHORT unit, in its place B/2-505 deployed, landing at Point Salines. The 82nd expanded its missions from the airhead at Salines to weed out Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces and Grenadan People's Revolutionary Army soldiers Each proceeding battalion pushed a single company forward with A/2-504 deploying only one company out of the entire brigade. The operation was flawed in several areas and identified areas needing attention to enhance the United States RDF doctrine. Newly issued Battledress Uniforms (BDUs) were not designed for the tropical environment; communication between Army ground forces and Navy and Air Force aircraft lacked interoperability and even food and other logistic support to ground forces were hampered due to communication issues between the services. The operation proved the division's ability to act as a rapid deployment force. The first aircraft carrying troopers from the 2–325th touched down at Point Salines 17 hours after H-Hour notification.[citation needed]

In March 1988, a brigade task force made up of two battalions from the 504th Infantry and 3d Battalion (Airborne), 505th Infantry, conducted a parachute insertion and air/land operation into Honduras as part of Operation Golden Pheasant. The deployment was billed as a joint training exercise, but the paratroopers were ready to fight. The deployment caused the Sandinistas to withdraw to Nicaragua. Operation Golden Pheasant prepared the paratroopers for future combat in an increasingly unstable world.[citation needed]

Panama: Operation Just Cause

On 20 December 1989, the "All-American", as part of the United States invasion of Panama, conducted their first combat jump since World War II onto Torrijos International Airport, Panama. The goal of the 1st Brigade task force, which was made up of the 1–504th and 2–504th INF as well as 4–325th INF and Company A, 3–505th INF, and 3–319th FAR, was to oust Manuel Noriega from power. They were joined on the ground by 3–504th INF, which was already in Panama. The invasion was initiated with a night combat jump and airfield seizures; the 82nd conducted follow-on combat air assault missions in Panama City and the surrounding areas of the Gatun Locks. The operation continued with an assault of multiple strategic installations, such as the Punta Paitilla Airport in Panama City and a Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF) garrison and airfield at Rio Hato, where Noriega also maintained a residence. The attack on La Comandancia (PDF HQ) touched off several fires, one of which destroyed most of the adjoining and heavily populated El Chorrillo neighborhood in downtown Panama City. The 82nd Airborne Division secured several other key objectives such as Madden Dam, El Ranacer Prison, Gatun Locks, Gamboa and Fort Cimarron. Overall, the operation involved 27,684 U.S. troops and over 300 aircraft, including C-130 Hercules, AC-130 Spectre gunship, OA-37B Dragonfly observation, and attack aircraft, C-141 and C-5 strategic transports, F-117A Nighthawk stealth aircraft and AH-64 Apache attack helicopters. The invasion of Panama was the first combat deployment for the AH-64, the HMMWV, and the F-117A. In the short six years since the Invasion of Grenada, Operation Just Cause demonstrated how quickly the US Armed Forces could adapt and overcome the mistakes and equipment interoperability issues to conduct a quick and decisive victory. In all, the 82nd Airborne Division suffered six of the 23 fatalities of the operation. The paratroopers began redeployment to Fort Bragg on 12 January 1990. Operation Just Cause concluded on 31 Jan 1990, just 42 days (D+42) since the invasion started.[citation needed]

Organization 1989

At the end of the Cold War the division was organized as follows:

- 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, North Carolina[58]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 1st Brigade[58]

- 2nd Brigade[58]

- 3rd Brigade[58]

- Aviation Brigade[67]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 1st Squadron, 17th Cavalry (Reconnaissance)[68]

- 1st Battalion, 82nd Aviation (Attack)[69]

- 2nd Battalion, 82nd Aviation (General Support)[70]

- Division Artillery[71][72][73]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Battery

- 1st Battalion, 319th Field Artillery (18 × M102 105mm towed howitzer)[74][75][71][73][58]

- 2nd Battalion, 319th Field Artillery (18 × M102 105mm towed howitzer)[76][74][71][73][58]

- 3rd Battalion, 319th Field Artillery (18 × M102 105mm towed howitzer)[77][74][71][73][58]

- Division Support Command

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 307th Medical Battalion

- 407th Supply & Transportation Battalion

- 782nd Maintenance Battalion[58]

- Company D, 82nd Aviation (Aviation Intermediate Maintenance)[78]

- 3rd Battalion, 73rd Armor[79]

- 3rd Battalion, 4th Air Defense Artillery[80]

- 307th Engineer Battalion[81][58]

- 82nd Signal Battalion[82][83][58]

- 313th Military Intelligence Battalion[84]

- 82nd Military Police Company

- 21st Chemical Company[85]

- 82nd Airborne Division Band[86]

Post–Cold War

Persian Gulf War

Seven months later the paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division were again called to war. Four days after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on 2 August 1990, the 4th Battalion (Airborne), 325th Infantry was the Division Ready Force 1 (DRF-1) and the initial ground force,[87] as President George Bush's "Line in the Sand"[88] speech to Saddam Hussein part of the largest deployment of American troops since Vietnam as part of Operation Desert Shield. The 4–325th INF immediately deployed to Riyadh and Thummim, Saudi Arabia. Their role was to guard the royal family as part of the agreement with King Fahd to station troops in and around the kingdom. The DRF 2 and 3 (1–325 and 2-325 INF, respectively) began drawing the "line in the sand" near al Jubail by building defenses for possible retrograde operations. Soon after, the rest of the division followed. There, intensive training began in anticipation of desert fighting against the heavily armored Iraqi Army.[citation needed]

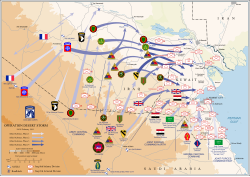

On 16 January 1991, Operation Desert Storm began when Allied warplanes attacked Iraqi targets. As the air war began, 2nd Brigade of the 82nd initially deployed near an airfield in the vicinity of the ARAMCO oil facilities outside Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia. While 1st Brigade and 3d Brigade consolidated at the Division HQ (CHAMPION Main) near Dhahran in Coinciding with the start of the air war, three National Guard Light-Medium Truck companies, the 253d (NJARNG), 1122d (AKARNG), and the 1058th (MAARNG) joined 2d Brigade of the 82nd. In the coming weeks using primarily the 5-Ton cargo trucks of these NG truck companies, the 1st Brigade moved north to "tap line road" in the vicinity of Rafha, Saudi Arabia. Eventually, these National Guard truck units effectively "motorized" the 325th Infantry, providing the troop ground transportation required for them to keep pace with the French Division Daguet during the incursion. The ground war began almost six weeks later. The 2–325th INF was the division's spearhead for the ground war who actually took positions over the Iraqi border 24 hours in advance of coalition forces at 0800hrs on 22 February 1991 on Objectives Tin Man and Rochambeau. On 23 February, 82nd Airborne Division paratroopers protected the XVIII Airborne Corps flank as fast-moving armor and mechanized units moved deep inside south-western Iraq. After the second day, the 1st Brigade moved forward to extend the Corps flank along with 3d Brigade. In the short 100-hour ground war, the 82nd drove deep into Iraq and captured thousands of Iraqi soldiers and tons of equipment, weapons, and ammunition. During that time, the 82nd's band and MP company processed 2,721 prisoners. After the liberation of Kuwait and the surrender of the Iraqi Army, the 82nd redeployed to Fort Bragg between 18 March and 22 April after being deployed for a period of seven months.[citation needed]

Hurricane Andrew

In August 1992, the division deployed a task force to the hurricane-ravaged area of South Florida to provide humanitarian assistance following Hurricane Andrew. For more than 30 days, troopers provided food, shelter and medical attention to the Florida population as part of the U.S. military Domestic Emergency Planning System. The 82nd was part of over 20,000 Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine, Coast Guard and an additional 6200 National Guard troops deployed for the disaster.[89]

They also provided security and a sense of safety for the victims of the storm who were without power, doors, windows and in many cases roofs. There were, as with all disasters, criminals trying to take advantage of the situation, in this case looters and thieves. The presence of the 82nd quickly eliminated that factor from the equation.[90]

Operation Restore Democracy: Haiti

On 16 September 1994, the 82nd Airborne Division joined Operation Restore Democracy. The 82nd was scheduled to make combat parachute jumps into Pegasus Drop Zone and PAPIAP Drop Zone (Port-au-Prince Airport), in order to help oust the military dictatorship of Raoul Cédras, and to restore the democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. At the same time, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell were negotiating with Cédras to restore Aristide to power, the 82nd's first wave was in the air, with paratroopers waiting at Green Ramp to air-land in Haïti once the airfields there had been seized. When the Haitian military verified from sources outside Pope Air Force Base that the 82nd was on the way, Cédras stepped down, averting the invasion.[citation needed]

Former Vice President Al Gore would later travel to Fort Bragg to personally thank the paratroopers of the 82nd for their actions, noting in a speech on 19 September 1994, that the 82nd's reputation was enough to change Cédras' mind:

But it did get a little close there for a while. As you may know, there were 61 planes in the air headed toward Haïti at the time they finally agreed. And at one point General Biamby came in and told General Cédras that he had just gotten word on his telephone that the airplanes had taken off from Pope Air Force Base, with soldiers from Fort Bragg, and that both disconcerted them and caused them to be suspicious of the intent of the negotiations, but it also created a situation where immediately after that, the key points they had been refusing to agree to were agreed to, a date certain, other matters that I won't go into in detail here.[citation needed]

Operations Safe Haven and Safe Passage

On 12 December 1994, the 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 505th Infantry, with the 2nd Platoon of Company C, 307th Engineer Battalion, deployed as part of Operations Safe Haven and Safe Passage. The battalion deployed from Fort Bragg while on Division Ready Force 1 to restore order against thousands of Cuban refugees who had attacked and injured a number of Air Force personnel and one marine while protesting their detainment at Empire Range along the Panama Canal. The battalion participated in the safeguarding of the Cuban refugees, a camp cordon and reorganization, and the active patrolling in and around the refugee camps in and around the Panamanian jungle along the Panama canal for two months. General Engineering support in the area of camp establishment/improvement operations was provided by the Sappers of the habitually associated Task Force Panther Engineer platoon, 2/C-307th. (Task Force Panther was commanded by LTC Lloyd J. Austin III, who would later be the first African American General to commander of U.S. Central Command and U.S. Secretary of Defense.) This support included the planning of camp power requirements, pouring of 78 concrete pads, three-foot bridges, a set of "mock doors" for airborne pre-jump training, and a system of decks for the muddy camp. During the deployment, the paratroopers experienced a 92-degree Christmas Day and returned to Fort Bragg on 14 February 1995.[citation needed]

Operation Joint Endeavor: Bosnia

Battalions of the 82nd prepared for a possible parachute jump to support elements of the 1st Armored Division which had been ordered to Bosnia-Herzegovina as part of Operation Joint Endeavor. Only after engineers of the 1st Armored Division bridged the Sava River on 31 December 1995 without hostilities did the 82nd begin to draw down against plans for a possible airborne operation there. The 82nd's 49th Public Affairs Detachment was deployed in support of the 1st Armored Division and air-landed in Tuzla with the 1AD TAC CP and began PA operations to include establishing the first communications in print and radio and covering the crossing of the Sava River by the main forces.[citation needed]

Centrazbat '97

In September 1997 the 82nd traveled to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan for CENTRAZBAT '97. Paratroopers from Ft. Bragg, NC flew 8000 miles on U.S. Air Force C-17s and jumped into an airfield in Shimkent, Kazakhstan. Forty soldiers from the three republics joined 500 paratroopers on the exercise-opening jump. Marine Gen. John Sheehan, then-commander in chief of the Atlantic Command, was first out of the aircraft. The 82nd joined units from Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, and Russia in the two-week-long, NATO peacekeeping training mission. Members of the international press and local reporters from WRAL-TV and the Fayetteville Observer were also embedded with the 82nd Airborne.[91]

Operation Allied Force: Kosovo

In March 1999 the TF 2–505th INF deployed to Albania and forward-deployed along the Albania/Kosovo border in support of Operation Allied Force, NATO's bombing campaign against Serbian forces in the Former Yugoslav Republic. In September 1999, TF 3–504th INF deployed in support of Operation Joint Guardian, replacing TF 2–505th INF. TF 3–504th INF was replaced in March 2000 by elements of the 101st Airborne Division. On 1 October 1999, the 1–508th ABCT (SETAF) made a combat jump in "Operation Rapid Guardian": 500-foot altitude jump near Pristina.[citation needed]

Global War on Terror

Operation Enduring Freedom II & III, 2002–2003

After 11 September attacks on the United States, the 82nd's 49th Public Affairs Detachment deployed to Afghanistan in October 2001 in support of Operation Enduring Freedom along with several individual 82nd soldiers who deployed to the Central Command area of responsibility to support combat operations.

In June 2002, elements of the division headquarters and TF Panther (HQ 3d Brigade; 1–504th INF, 1–505th INF, 3–505th INF, 1–319th FA) deployed to Afghanistan. In January 2003, TF Devil (HQ 1st Brigade, 2–504th INF, 3–504th INF, 2–505th INF, 3–319th FA) relieved TF Panther.[citation needed]

Operation Iraqi Freedom I, 2003–2004

In March 2003, 2–325 of the 2nd BCT was attached to the 75th Ranger Regiment as part of a special operations task force to conduct a parachute assault to seize Saddam International Airport in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. On 21 March 2003, Company D, 2-325 crossed the Saudi Arabia–Iraq border as part of Task Force Hunter to escort HIMARS artillery systems to destroy Iraqi artillery batteries in the western Iraqi desert. Upon cancellation of the parachute assault to seize the airport, the battalion returned to its parent 2nd Brigade at Talil Airfield near An Nasariyah, Iraq. The 2nd Brigade then conducted operations in Samawah, Fallujah, and Baghdad. The brigade returned to the United States by the end of February 2004.[92]

The early days of the 82nd Airborne's participation in the deployment were chronicled by embedded journalist Karl Zinsmeister in his 2003 book Boots on the Ground: A Month with the 82nd Airborne in the Battle for Iraq.

In April 2003, according to Human Rights Watch, soldiers from a subordinate unit, the 325th Infantry, allegedly fired indiscriminately into a crowd of Iraqi civilians protesting their presence in the city of Fallujah. They killed and wounded many civilians. The battalion suffered no casualties.[93]

The 3rd Brigade deployed to Iraq in the summer, redeploying to the U.S. in spring 2004. The 1st Brigade deployed in January 2004. The last units of the division left by the end of April 2004. The 2nd Brigade deployed on 7 December 2004 to support the free elections and returned on Easter Sunday in 2005. During this initial deployment, 36 soldiers from the division were killed and about 400 were wounded, out of about 12,000 deployed. On 21 July 2006, the 1st Battalion, 325th Infantry Regiment, along with a platoon from Battery A, 2nd Battalion, 319th Field Artillery Regiment and a troop from 1st Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment deployed to Tikrit, Iraq, returning in December 2006. Just days after returning home, the battalion joined the rest of the 2nd Brigade in another deployment scheduled for the beginning of January 2007.[citation needed]

Rapid deployment operations

Afghanistan

In late September 2004 the National Command Authority alerted TF 1–505th INF for an emergency deployment to Afghanistan in support of that October's (first free) elections.[citation needed]

Iraq

In December 2004, the task forces based on 2–325th AIR and 3–325th AIR deployed to Iraq to provide a safe and secure environment for the country's first-ever free national elections. Thanks in part to the efforts of 2d Brigade paratroopers, more than eight million Iraqis were able to cast their first meaningful ballots.[citation needed]

Operation Enduring Freedom VI, 2005–2008

The 1st Brigade of the 82nd deployed in April 2005 in support of OEF 6, and returned in April 2006. 1st Battalion, 325th Infantry Regiment deployed in support of OEF 6 from July through November 2005.[citation needed]

In March 2006, 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne) and Security Forces (SECFOR) consisting of mostly Rangers, deployed as part of a special operations task force to conduct various operations and security. 2007 February 18, seven soldiers from the task force died in a helicopter crash. The deployment would end a month later (March 2007).[94]

In January 2007, then Maj. Gen. David M. Rodriguez deployed the division headquarters to Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan, accompanied by 4th BCT and the Aviation Brigade, as Commander, Combined Joint Task Force-82 (CJTF-82)and Regional Command – East for Operation Enduring Freedom VIII. The 3d BCT, 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) was extended for 120 days to increase the troop strength against the Taliban spring offensive. Extended to 15-month deployment, 4th BCT, which included 1–508th Infantry Regiment, 2–508th Infantry Regiment, and 4–73rd Cavalry Regiment, 2–321st Field Artillery, and 782nd Brigade Support Battalion, was commanded by then Col. Martin P. Schweitzer and remained in Khowst Province from January 2007 until April 2008. The 2–508th IR worked to establish and maintain firebases in and around the Ghazni province while actively patrolling their operational area. The 1–508 PIR served in Regional Command-South. Working mostly out of Kandahar province as the theater tactical force, they mentored the Afghan National Security Force (ANSF), conducting combined operations with both ANSF and NATO partners in the Helmand province.[95] Supporting the division were the 36th Engineer Brigade, and the 43d Area Support Group.

Hurricane Katrina

The 82nd Airborne's 3rd Brigade, 505th Infantry Regiment, and the division's 319th Field Artillery Regiment along with supporting units deployed to support search-and-rescue and security operations in New Orleans, Louisiana after the city was flooded by Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. About 5,000 paratroopers commanded by Major General William B. Caldwell IV, operated out of New Orleans International Airport.[citation needed]

Reorganization

In January 2006, the division began reorganizing from a division based organization to a brigade combat team-based organization. Activated elements include a 4th Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division (1–508th INF, 2–508th INF, 4–73rd Cav (RSTA), 2–321st FA, 782nd BSB, and STB, 4th BCT) and the inactivation of the Division Artillery, 82nd Signal Battalion, 307th Engineer Battalion, and 313th Military Intelligence Battalion. The 82nd Division Support Command (DISCOM) was redesignated as the 82nd Sustainment Brigade. A pathfinder unit was reactivated within the 82nd when the Long Range Surveillance Detachment of the inactivating 313th Military Intelligence Battalion was transferred to the 2d Battalion, 82nd Aviation Regiment and converted to a pathfinder role as the battalion's Company F.[citation needed]

Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2006–2009, "The Surge"

In December 2006, 2nd BCT deployed once again to Iraq in support of OIF. On 4 January 2007, 2nd Brigade deployed to northern Bagdad in the Sumer and Talbiyah district, returning 8 March 2008. On 4 June 2007, 1st Brigade deployed to Southern Iraq, returning 15 July 2008. Since the deployment began, the division has lost 37 paratroopers. Since 11 September 2001, the division has lost 20 paratroopers in Afghanistan and 101 paratroopers in Iraq.[citation needed]

Operation Enduring Freedom, 2007–2008

In January 2007, then Maj. Gen. David M. Rodriguez deployed the division headquarters to Bagram, Afghanistan, accompanied by 4th BCT and the Aviation Brigade, as Commander, Combined Joint Task Force-82 (CJTF-82)and Regional Command – East for Operation Enduring Freedom VIII. The 3d BCT, 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) was extended for 120 days to increase the troop strength against the Taliban spring offensive. Extended to 15-month deployment, 4th BCT, which included 1–508th Infantry Regiment, 2–508th Infantry Regiment, and 4–73rd Cavalry Regiment, 2–321st Field Artillery, and 782nd Brigade Support Battalion, was commanded by then Col. Martin P. Schweitzer and remained in Khowst Province from January 2007 until April 2008. The 2–508th IR worked to establish and maintain firebases in and around the Ghazni province while actively patrolling their operational area. The 1–508 PIR served in Regional Command-South. Working mostly out of Kandahar province as the theater tactical force, they mentored the Afghan National Security Force (ANSF), conducting combined operations with both ANSF and NATO partners in the Helmand province.[95] Supporting the division were the 36th Engineer Brigade, and the 43d Area Support Group.

Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom and New Dawn, 2008–2011

In December 2008, the 3d BCT deployed to Baghdad, Iraq and redeployed to Ft. Bragg in November 2009. In August 2009, 1st BCT deployed once again to Iraq and redeployed late July 2010.

During the months of August and September 2009, 4th BCT deployed again to Afghanistan and returned in August 2010 having lost 38 soldiers.[citation needed]

In May 2011 1–505 (Task Force 1 Panther) deployed to Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Dispersed throughout the country, 1st battalion was attached to various Special Operations elements. 1st battalion redeployed to Fort Bragg, NC in February 2012 having lost two paratroopers.

The 2d Brigade deployed to the Anbar Province in Iraq in May 2011 for the last time in support of Operation New Dawn with the mission to advise, train and assist the Iraqi Security Forces and lead the responsible withdrawal of U.S. Forces - Iraq. Elements of 2d Brigade were among the last US combat units to withdraw from Baghdad. The brigade suffered the loss of the last American service member in Iraq, SPC. David E. Hickman, on 14 November 2011. They were part of the long convoy of equipment and troops who exited Iraq into Kuwait as OIF came to an end.[96]

2010 Haiti earthquake – Operation Unified Response

As part of Operation Unified Response, the 2d BCT, on rotation as the division's Global Response Force, was alerted and deployed forces to Haiti later that same day for the mission to provide humanitarian assistance following the devastating earthquake in Haiti.[96] Paratroopers distributed water and food during the 2010 Haiti earthquake relief.[97]

Just two months following redeployment from Haiti in 2010, elements of 2d BCT (Red Falcons) deployed to Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom to serve as trainers for the Afghan National Security Forces.[98] In October 2011, the Division Headquarters returned to Afghanistan, where they relieved the 10th Mountain Division as the Headquarters of Regional Command-South.

In February 2012, 4th BCT deployed to Kandahar province. Taliban commander Mullah Dadullah, formed an overwhelming force in Kandahar. Zhari district in southern Kandahar is where Dadullah was recruiting a high number of jihadists. 4th BCT of the 82nd held the 5-month siege from March 2012 to the end of July, witnessing some of the most intense combat since the initial deployments since 2001, 4th BCT inflicted massive casualties among the Taliban. Performing with an almost perfect strategic plan, 4th BCT drove Dadullah and his men out of Kandahar to the Northeastern province of Kunar, where Dadullah was killed by airstrikes.[citation needed]

As of April 2012, the 1st BCT was deployed to Afghanistan, operating in Ghazni Province, Regional Command-East. The paratroopers took control of Ghazni from the Polish Armed Forces, allowing the Polish Task Force White Eagle (pl:Polski Kontyngent Wojskowy w Afganistanie) to consolidate around the provincial seat in northern Ghazni.[99]

In June 2012, the 3rd Brigade Combat Team deployed as part of the Global Response Force (GRF) in support of heavy combat operations conducted by the 1st Infantry Division. The Brigade was spread across much of RC-East Afghanistan.

In December 2013, elements of the 4th Brigade deployed again to Afghanistan and they were joined by the 1st Brigade in spring 2014.[100] Since 11 September 2001, the division has lost 106 paratroopers in Afghanistan and 139 paratroopers in Iraq.[citation needed]

Operation Inherent Resolve

On 19 December 2014, Stars & Stripes announced 1,000 soldiers from the 82nd Airborne's 3rd Brigade Combat Team would deploy to Iraq to train, advise, and assist Iraq's Security Forces.[101]

On 3 November 2016, it was reported that 1,700 soldiers from the 2d Brigade Combat Team will deploy to the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility in Iraq, to take part in Operation Inherent Resolve. They will replace the 2d Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division and will advise and assist Iraqi Security Forces currently trying to retake Mosul from ISIS fighters.[102]

On 27 March 2017, it was reported that 300 paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne's 2nd Brigade Combat Team will temporarily deploy to northern Iraq to provide additional advise-and-assist combating ISIS, particularly to speed up the offensive against ISIS in Mosul.[103][104]

On 31 December 2019, approximately 750 soldiers from the 82nd Airborne's Immediate Response Force were authorized to be deployed to Iraq in response to recent events which saw the United States' embassy in the country stormed.[105]

From the start of January 2017 to September 2017, the division suffered the loss of five paratroopers killed in action.[106][107][108][109][110]

Syria intervention

It was confirmed in July 2020 that the 82nd Airborne Division did in fact have combat deployments in Syria.[111][112]

Operation Freedom's Sentinel

The 1st BCT deployed to Afghanistan in support of Operation Freedom's Sentinel from June 2017 to March 2018.[113][114][115] Two soldiers were killed in action when their convoy was purposefully hit by a vehicle filled with explosives.[116]

The 3rd BCT deployed to Afghanistan in support of Operation Freedom's Sentinel from July 2019 to March 2020. In February 2020 soldiers from the 1st BCT, 10th Mountain Division were deployed to Afghanistan to replace the 3rd BCT as part of a unit rotation.[117]

Iranian threat in Iraq

The 82nd Airborne rapid response capabilities were called upon after rioters outside of the U.S. embassy in Baghdad, Iraq breached the outer gates. The rioters were identified as Iranian-backed militias operating in Iraq. On 1 January 2020, the first 750 troops began mobilizing to Kuwait and bases in the Baghdad area. During this mobilization the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani was killed in a U.S. airstrike at the Baghdad airport. The Iranian military influence on Iraqi militia groups was believed to be behind the rioting at the U.S. embassy and was also believed to be planning further action against U.S. diplomats and citizens in Iraq. The actions by the Iranians and the U.S. have increased tensions in the region not seen since before the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The 82nd airborne was among the first military units to be mobilized in response to this escalation and tensions. An additional 3,500 to 4,000 troops were ordered to deploy to Kuwait in response to Iranian threats in the region.[118][119]

Evacuation of Kabul

In August 2021, elements of the 82nd Airborne Division, particularly the Immediate Response Force, deployed to Afghanistan to secure the evacuation of American diplomats and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa applicants as the Taliban seized much of the country and converged on Kabul. Throughout Operation Allies Refuge, the 82nd Airborne Division served as the Operational Command, Task Force 82.

Operation Allies Refuge, led by Major General Chris Donahue, is a combined and joint ongoing NATO command post composed of forces representing NATO allied Nations, 1st Brigade Combat Team "Devil", aviation capabilities from the 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade "Pegasus", medical capabilities from the 44th Medical Brigade, riot control capabilities from the 16th Military Police Brigade, 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit, and the 3rd Expeditionary Sustainment Command who oversaw sustainment in the joint operational area from a command post in Kuwait.[120][121]

Meetings

The Center for Additive Manufacturing and Logistics (CAMAL) met with Den-McKay and other 82nd Airborne Division members on June 3, 2021. They were both looking to collaborate with each other by “providing a system to solicit, collect, and assess innovative ideas”. 2 projects were called in for proposition, the first being the engineering of lighter and more efficient weaponry to increase military capability. The other would fix the malfunctioning of equipment machinery dropped from an airplane. They wanted to establish these features while trying not to increase the weight.[122]

Representative member Richard Hudson delivers a speech on Fort Bragg on May 19, 2022. He is there to “discuss two critical Military Construction needs” in the fort, stating that there has been a “lack of attention conventional forces have received.”. The first of these needs is a Multipurpose Training Range (MPTR), specifically 4 as per its requirement, but lacking none thereof. Units therefore must leave to find other alternative locations for training. This allegedly creates a loss in combat readiness. A Child Development Center was requested as the 2nd need for Fort Bragg. Childcare services in the fort are said to be lacking as the centers at the time of this speech can take months to register. These changes are on the FY23 MilCon/VA bill and are pending as of today.[123] [needs update]

Structure

82nd Airborne Division consists of a division headquarters and headquarters battalion, three infantry brigade combat teams, a division artillery, a combat aviation brigade, and a sustainment brigade.[124][125]

Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion

Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion

- 82nd Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

- Operations Company (Company A)

- Intelligence and Sustainment Company (Company B)

- Division Signal Company (Company C)

- 82nd Airborne Division Band

US Army Advanced Airborne School

US Army Advanced Airborne School

49th Public Affairs Detachment

49th Public Affairs Detachment

1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team (BCT) "Devil Brigade"

1st BCT's HHC

1st Battalion, 504th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 504th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment

3rd Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment

3rd Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment

3rd Battalion, 319th Airborne Field Artillery Regiment (AFAR)

3rd Battalion, 319th Airborne Field Artillery Regiment (AFAR)

127th Brigade Engineer Battalion (BEB)

127th Brigade Engineer Battalion (BEB)

307th Brigade Support Battalion (BSB)

307th Brigade Support Battalion (BSB)

2nd Infantry BCT "Falcon Brigade"[126]

2nd BCT's HHC

2nd BCT's HHC

1st Battalion, 325th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 325th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 508th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 508th Infantry Regiment

1st Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment

1st Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 319th AFAR

2nd Battalion, 319th AFAR

37th BEB

37th BEB

407th BSB

407th BSB

3rd Infantry BCT "Panther Brigade"

3rd BCT's HHC

3rd BCT's HHC

1st Battalion, 505th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 505th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 505th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 505th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 508th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 508th Infantry Regiment

5th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment

5th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment

1st Battalion, 319th AFAR

1st Battalion, 319th AFAR

307th BEB

307th BEB

82nd BSB

82nd BSB

82nd Airborne Division Artillery (Has training and readiness oversight of field artillery battalions, which remain organic to their brigade combat teams)

Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 82nd Airborne Division Artillery[127]

Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 82nd Airborne Division Artillery[127]

Combat Aviation Brigade (CAB), 82nd Airborne Division "Pegasus Brigade"[128]

HHC, CAB, 82nd Airborne Division[67]

HHC, CAB, 82nd Airborne Division[67]

Company D, 82nd Aviation Regiment, MQ-1C Gray Eagle (Activated as a separate MQ-1C Gray Eagle UAV unit on 16 February 2017. It is not assigned to any of the existing helicopter battalions of the division's CAB.)[129]

Company D, 82nd Aviation Regiment, MQ-1C Gray Eagle (Activated as a separate MQ-1C Gray Eagle UAV unit on 16 February 2017. It is not assigned to any of the existing helicopter battalions of the division's CAB.)[129]

1st Squadron (Heavy Attack/Reconnaissance), 17th Cavalry Regiment, AH-64E Apache[130]

1st Squadron (Heavy Attack/Reconnaissance), 17th Cavalry Regiment, AH-64E Apache[130]

1st Battalion (Attack), 82nd Aviation Regiment, AH-64E Apache[131]

1st Battalion (Attack), 82nd Aviation Regiment, AH-64E Apache[131]

2nd Battalion (Assault), 82nd Aviation Regiment, UH-60M Black Hawk[132]

2nd Battalion (Assault), 82nd Aviation Regiment, UH-60M Black Hawk[132]

3rd Battalion (General Support), 82nd Aviation Regiment, CH-47 Chinook and UH-60 Black Hawk

3rd Battalion (General Support), 82nd Aviation Regiment, CH-47 Chinook and UH-60 Black Hawk

122nd Aviation Support Battalion

122nd Aviation Support Battalion

82nd Airborne Division Sustainment Brigade[133]

The division's 3rd Brigade was known as the Golden Brigade, 1970–2000. The division's 4th Brigade Combat Team inactivated in fall of 2013: the Special Troops Battalion, 4th BCT;[134] the 2nd Battalion, 321st Field Artillery Regiment; and the 782nd Brigade Support Battalion were inactivated with some of the companies of the 782nd used to augment support battalions in the remaining three brigades. The 4th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry joined the 1st Brigade Combat Team and formed the core of the newly activated 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment. The 2nd Battalion, 508th Infantry Regiment joined the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, while the 1st Battalion, 508th Infantry Regiment joined the 3rd Brigade Combat Team.[citation needed]

Traditions

To commemorate the 1944 Waal assault river crossing made by the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 307th Engineer Battalion (Airborne) during Operation Market Garden, an annual Crossing of the Waal competition is staged on the anniversary of the operation at McKellar's Lake near Fort Bragg. The winning company receives a paddle.[135] The paddle signifies that in the original crossing, many paratroopers had to row with their weapons because the canvas boats lacked sufficient paddles.[citation needed]

Honors

Campaign participation credit

- World War I

- St. Mihiel

- Meuse-Argonne

- Lorraine 1918

- World War II

- Sicily

- Naples-Foggia

- Normandy (with arrowhead)

- Rhineland (with arrowhead)

- Ardennes-Alsace

- Central Europe

- Armed Forces Expeditions

- Dominican Republic

- Grenada

- Panama

- Southwest Asia

- Defense of Saudi Arabia

- Liberation and Defense of Kuwait

- Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)

- Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)

- Operation New Dawn (OND)

- Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR)

Medal of Honor recipients

World War I

- Lt. Col. Emory J. Pike

- Corp. Alvin C. York

World War II

- Pvt. John R. Towle

- Pfc. Charles N. Deglopper

- 1st Sgt. Leonard A. Funk Jr.

- Pvt. Joe Gandara[136]

Vietnam War

- SSG Felix M. Conde-Falcon[136]

- Master Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez[137][138]

Decorations

Presidential Unit Citation (Army) for Sainte-Mère-Église.

Presidential Unit Citation (Army) for Sainte-Mère-Église.- Presidential Unit Citation (Army) for Operation Market Garden.

- Presidential Unit Citation (Army) for Chiunzi Pass/Naples/Foggia awarded to the following units of the 82nd Airborne: 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, 307th Engineer Battalion (2nd), 80th Anti-aircraft Battalion and Company H, 504 PIR

- Presidential Unit Citation (Army) for the Battle of Samawah, April 2003, awarded to the following unit of the 82nd Airborne: 2nd Brigade Combat Team (325th Airborne Infantry Regiment)

- Presidential Unit Citation (Army) for Operation Turki Bowl, OIF, November 2007, awarded to the following unit of the 82nd Airborne: 5th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry, 3rd Brigade, 505th PIR

Valorous Unit Citation (Army) for Operation Iraqi Freedom (3rd Brigade Combat Team, OIF 1)

Valorous Unit Citation (Army) for Operation Iraqi Freedom (3rd Brigade Combat Team, OIF 1)- Valorous Unit Citation (Army) for actions on the objective in the Baghdad neighborhood of Ghazaliya. While attached to the 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division. Cited in Department of the Army General Order 2009–10

Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) for Southwest Asia.

Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) for Southwest Asia. Superior Unit Award (Army) US Army Garrison, Ft Bragg 11 September 2001 – 15 April 2006 Cited in DAGO 2009–29

Superior Unit Award (Army) US Army Garrison, Ft Bragg 11 September 2001 – 15 April 2006 Cited in DAGO 2009–29 French Croix de Guerre with Palm, World War II for Sainte-Mère-Église.

French Croix de Guerre with Palm, World War II for Sainte-Mère-Église.- French Croix de Guerre with Palm, World War II for Cotentin.

- French Croix de Guerre, World War II, Fourragère

- Belgian Fourragere 1940

- Cited in the Order of the Day of the Belgian Army for action in the Ardennes