Skegness

| Skegness | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Skegness clock tower and seafront amusements | |

The beach with the pier in the background | |

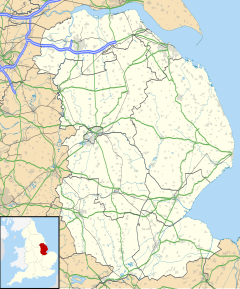

Location within Lincolnshire | |

| Population | 21,128 (2021 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TF5663 |

| • London | 115 mi (185 km) S |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SKEGNESS |

| Postcode district | PE24, PE25 |

| Dialling code | 01754 |

| Police | Lincolnshire |

| Fire | Lincolnshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Skegness (/ˌskɛɡˈnɛs/ skeg-NESS) is a seaside town and civil parish in the East Lindsey District of Lincolnshire, England. On the Lincolnshire coast of the North Sea, the town is 43 miles (69 km) east of Lincoln and 22 miles (35 km) north-east of Boston. With a population of 19,579 as of 2011, it is the largest settlement in East Lindsey. It also incorporates Winthorpe and Seacroft, and forms a larger built-up area with the resorts of Ingoldmells and Chapel St Leonards to the north. The town is on the A52 and A158 roads, connecting it with Boston and the East Midlands, and Lincoln respectively. Skegness railway station is on the Nottingham to Skegness (via Grantham) line.

The original Skegness was situated farther east at the mouth of The Wash. Its Norse name refers to a headland which sat near the settlement. By the 14th century, it was a locally important port for coastal trade. The natural sea defences which protected the harbour eroded in the later Middle Ages, and it was lost to the sea after a storm in the 1520s. Rebuilt along the new shoreline, early modern Skegness was a small fishing and farming village, but from the late 18th century members of the local gentry visited for holidays. The arrival of the railways in 1873 transformed it into a popular seaside resort. This was the intention of The 9th Earl of Scarbrough, who owned most of the land in the vicinity; he built the infrastructure of the town and laid out plots, which he leased to speculative developers. This new Skegness quickly became a popular destination for holiday-makers and day trippers from the East Midlands factory towns. By the interwar years the town was established as one of the most popular seaside resorts in Britain. The layout of the modern seafront dates to this time and holiday camps were built around the town, including the first Butlin's holiday resort which opened in Ingoldmells in 1936.

The package holiday abroad became an increasingly popular and affordable option for many British holiday-makers during the 1970s; this trend combined with declining industrial employment in the East Midlands to harm Skegness's visitor economy in the late 20th century. Nevertheless, the resort retains a loyal visitor base and has increasingly attracted people visiting for a short holiday alongside their trip abroad. Tourism increased following the recession of 2007–09 owing to the resort's affordability. In 2011, the town was England's fourth most popular holiday destination for UK residents, and in 2015 it received over 1.4 million visitors. It has a reputation as a traditional English seaside resort owing to its long, sandy beach and seafront attractions which include amusement arcades, eateries, Botton's fairground, the pier, nightclubs and bars. Other visitor attractions include Natureland Seal Sanctuary, a museum, an aquarium, a heritage railway, an annual carnival, a yearly arts festival, and Gibraltar Point nature reserve to the south of the town.

Despite the arrival of several manufacturing firms since the 1950s and Skegness's prominence as a local commercial centre, the tourism industry remains very important for the economy and employment. But the tourism service economy's low wages and seasonal nature, along with the town's aging population, have contributed towards high levels of relative deprivation among the resident population. Poor transport and communication links are barriers to economic diversification. Residents are served by five state primary schools and a preparatory school, two state secondary schools (one of which is selective), several colleges, a community hospital, several churches and two local newspapers. The town is home to a police station, a magistrates court and a lifeboat station.

Geography

Topography and geology

The civil parish of Skegness includes most of the linear settlement of Seacroft to the south and the village of Winthorpe and the suburban area of Seathorne to the north, all of which have been absorbed into the town's urban area. The neighbouring parishes are: Ingoldmells to the north, Addlethorpe to the north-west, Burgh le Marsh to the west and Croft to the south.[2] The town is approximately 22 miles (35 km) north-east of Boston and 43 miles (69 km) east of Lincoln.[3][4]

Skegness fronts the North Sea. It is located on a low-lying flat region called Lincoln Marsh, which runs along the coast between Skegness and the Humber and separates the coast from the upland Wolds.[5] Much of the parish's elevation is close to sea level, although a narrow band along the seafront is 4–5 m (13–16 ft) above peaking at 6 m (20 ft) on North Parade; the A52 road is elevated at 4 m (13 ft); and there is also a short narrow bank parallel to the shoreline between the North Shore Golf Club and Seathorne which is 10 m (33 ft) above sea level.[6]

The bedrock under the town is part of the Ferriby Chalk Formation, a sedimentary layer formed around 100 million years ago during the Cretaceous period; it runs north-west from Skegness in a narrow band to Fotherby and Utterby north of Louth in the Wolds. The surface layers are tidal-flat deposits of clay and silt, deposited since the end of the last ice age and during the Holocene epoch (the last 11,800 years). The shoreline consists of blown sand and beach deposits in the form of clay, silt and sand.[7][8]

Coastal erosion

There has been coastal erosion in the area for thousands of years,[9] though it was relatively sheltered until the Middle Ages by a series of offshore barrier islands or shoals made up of boulder clay. Rising sea levels and more intense sea storms from the 13th century onward very likely eroded these islands, increasingly exposing the Skegness coast to the tides.[10] Records from the Middle Ages show that local people maintained sand banks as a form of sea defence; fines were levied for grazing animals on the dunes, which could weaken the defences. Skegness was flooded in 1525 or 1526, requiring the village to be rebuilt inland, and loss of land continued during the century. A clay embankment, Roman Bank, was built in the late 16th century and was followed in c. 1670 by another closer to the sea (Green Bank), running from what is now North Shore Road to Cow Bank, following a line from St Andrew's Drive to Drummond Road.[11] By the late 19th century, sands were accreting at Skegness; the retaining sea wall erected in 1878 was designed to support the resort town's seafront development rather than to protect it from the sea.[12] Nevertheless, this wall largely saved the town during the 1953 flood, when only gardens, the amusements and part of the pier were damaged.[13]

In the early 21st century, Longshore drift carries particles of sediment southwards along the Lincolnshire coast.[14][9] At Skegness, the sand settles out in banks which run at a slight south-west angle to the coast.[9] Sand continues to accrete at the southern end of the town's shore, but coastal erosion continues immediately north of the settlement.[15] Modern sea defences have been built along a 15-mile (24 km) stretch of coast between Mablethorpe (to the north) and Skegness to prevent erosion, but currents remove sediment and the defences hinder dune development; a nourishment scheme began operation in 1994 to replace lost sand.[14][9]

Climate

The British Isles experience a temperate, maritime climate with warm summers and cool winters.[16] Lincolnshire's position on the east of the British Isles allows for a sunnier and warmer climate relative to the national average, and it is one of the driest counties in the United Kingdom.[17] In Skegness, the average daily high temperature peaks in August at 20.4 °C (68.7 °F) and a peak average daily mean of 16.7 °C (62.1 °F) occurs in July and August. The lowest daily mean temperature is 4.4 °C (39.9 °F) in January; the average daily high for that month is 7.0 °C (44.6 °F) and the daily low is 1.9 °C (35.4 °F).[18]

| Climate data for Skegness,[a] elevation: 6 m (20 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1904–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.8 (58.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

27.1 (80.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.4 (90.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.6 (12.9) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52.3 (2.06) |

40.4 (1.59) |

37.6 (1.48) |

37.1 (1.46) |

45.0 (1.77) |

52.4 (2.06) |

57.5 (2.26) |

62.2 (2.45) |

50.6 (1.99) |

63.3 (2.49) |

58.3 (2.30) |

55.5 (2.19) |

612.2 (24.10) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.2 | 9.6 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 115.0 |

| Source: European Climate Assessment and Dataset.[18] | |||||||||||||

- ^ Weather station is located 0.5 miles (0.8 km) from the Skegness town centre.

History

Prehistoric and medieval

There is evidence of late Iron-Age and early Roman saltmaking activity in the Skegness area.[19] Place names and a report of a castle in the medieval settlement have been interpreted as evidence that a Roman fort existed in the town before being lost to the sea in the late Middle Ages.[20] The archaeologist Charles Phillips suggested that Skegness was the terminus of a Roman road running from Lincoln through Burgh le Marsh and was also the location of a Roman ferry which crossed The Wash to Norfolk.[21] If the Roman fortifications indeed existed, it is likely that the Anglo-Saxons used them as a coastal shore fort. Later, the Vikings settled in Lincolnshire and their influence is detected in many local place names.[22] Skegness's name combines the Old Norse words Skeggi and ness, and means either "Skeggi's headland" or "beard-shaped headland";[23] Skeggi (meaning "bearded one") may be the name of a Viking settler or it could derive from the Old Norse word skegg "beard" and have been used to describe the shape of the landform.[24] Skegness was not named in the Domesday Book of 1086. It is usually identified with the Domesday settlement called Tric.[25][n 1] The historian Arthur Owen and the linguist Richard Coates have argued that Tric derived its name from Traiectus, Latin for "crossing", referring to the Roman ferry that Phillips argues launched from Skegness.[33][n 2] The name Skegness appears in the 12th century,[35] and further references are known from the 13th.[34]

Natural sea defences (including a promontory or cape, as the place name suggests, and barrier shoals and dunes) protected a harbour at Skegness in the Middle Ages.[36] It was relatively small and its trade in the 14th century was predominantly coastal; its economic fortunes were probably closely related to those of nearby coastal ports, such as Wainfleet, which in turn depended on the larger port at Boston which was heavily involved in the wool trade.[37] It was also an important fishing port.[38] During the medieval period the offshore barrier islands which sheltered the coast were destroyed, very likely in the 13th century during a period of exceptionally stormy weather. This left the coast exposed to the sea and in a constant state of change; later in the Middle Ages, frequent storms and floods eroded sea defences.[39] Between the 14th and 16th centuries, Skegness was one of several coastal settlements to incur major loss of land to the sea. Local people attempted to make artificial banks, but they were costly.[40] Rising sea levels further threatened the coast[41] and in 1525 or 1526 Skegness was largely washed away in a storm, along with the hamlets of East and West Meales.[42][43][n 3]

Later fishing and farming village

After the flooding, Skegness was rebuilt along the new coastline.[45] By 1543, when the antiquarian John Leland visited the town, he noted that "For old Skegnes is now buildid a pore new thing";[42] the settlement was principally a small farming and fishing village throughout the early modern period,[46] with the marshland providing good summer pasture for sheep.[47] Over the course of the 16th century, the sea continued to encroach into the land at Skegness, while depositing sand banks further south, leading to the creation of Gibraltar Point.[48][47] Roman Bank, a clay sea defence upon which the A52 road now runs through Skegness, was built in the latter part of the century.[49][50][51] Much of the land in and around Skegness came into the hands of Nicholas Saunderson, 1st Viscount Castleton,[52] who enclosed 400 acres (160 hectares) of saltmarsh in 1627 and later in the 17th century reclaimed more marshland which had emerged from the sea, sheltered behind the growing Gibraltar Point.[53] His descendant was responsible for erecting Green Bank between Roman Bank and the shore in c. 1670, allowing more lands to be converted to agricultural use.[54] The Lords Castleton had enclosed a large portion of the land around Skegness by 1740,[55] over 800 acres (320 hectares).[56] The Castleton estate passed through the male line which became extinct in 1723 on the death of the 5th Viscount, who bequeathed his estate to his cousin Thomas Lumley; in 1739 Lumley became 3rd Earl of Scarbrough. By 1845, the Scarbrough estate comprised 1,219 acres (493 hectares) at Skegness.[53][n 4] Although the population rose above 300 by 1851,[59] the settlement "was still very much an undeveloped village of fishermen, farmers and farm hands" in the early 1870s.[60]

Early resort

Local gentry began visiting the village for leisure reasons from the late 18th century.[n 5] The sea air was thought to have health-giving qualities.[61] To capitalise on this trend, the Skegness Hotel opened in 1770; visitors could reach it by omnibus from Boston, which was the terminus of several stagecoaches.[63] The first reference to bathing machines on Skegness's shores dates to 1784 though they are thought to have been present earlier.[60] Private houses also opened their doors to lodgers,[60] and other hotels opened.[64][65] Born and raised at Somersby, the poet Alfred Tennyson (later Lord Tennyson) holidayed at Skegness as a young man, often taking walks along the shore from his lodgings at Mary Walls' Moat House on the sea bank;[66] some scholars have drawn parallels between his poetry and the landscape he encountered on these visits.[67][68]

The railways and the modern resort

The East Lincolnshire Railway, running along the coast between Boston and Grimsby, opened in 1848. In 1871, a branch line was built to Wainfleet All Saints with rolling stock operated by the Great Northern Railway; an extension to Skegness was approved by GNR shareholders that year[69] and the railways arrived at Skegness in 1873.[70] The line was designed to bring day trippers to the seaside.[60][71] Rising wages and better holiday provision meant that some working-class people from the East Midlands factory towns like Nottingham, Derby and Leicester could afford to have a holiday for the first time.[71][72] With agriculture in depression, the major landowner Richard Lumley, 9th Earl of Scarbrough had seen his local rental income decline; his agent, H. V. Tippet, decided that the earl's fortunes might be revived if he turned Skegness into a seaside resort.[73][n 6] A road plan was developed and the earl took out a mortgage of £120,000 to fund developments. In 1878, the full plan laid out plots for 787 houses in a grid-aligned settlement on 96 acres (39 hectares) of land between the shoreline and Roman Bank north of the High Street.[73][76] Scarbrough Avenue would run inland from the centre of the Parade and was bisected by Lumley Avenue, with a new church in the roundabout. At the end of Scarbrough Avenue would be a pier.[77]

The earl spent thousands of pounds on laying roads and the sewerage system, and building the sea wall (the latter of which was finished in 1878).[78][79] He provided or invested in other amenities, including the gas and water supply, Skegness Pier (opened in 1881), the pleasure gardens (finished in 1881), the steamboats (launched by 1883) and bathing pools (1883).[80][81] He donated land and money towards the building of St Matthew's Church, two Methodist chapels, a school and the cricket ground.[82][83] Housebuilding was left to speculative builders; the earliest development was concentrated along Lumley Road, which offered a direct route from the train station to the seafront. Newspapers across the Midlands advertised properties, and shops began opening.[84] By 1881 almost a thousand people had moved into the town.[85] According to the local historian Winston Kime, Skegness had become known as a "trippers' paradise" by 1880.[65] The August bank holiday in 1882 saw 20,000 descend on the town; they came to enjoy the beach and the sea, the many games and amusements that had popped up in the town, the pleasure boat trips that had just started launching from the pier, and the donkey rides.[86] Building contracted after the 1883 season,[87] although in 1888 the accreted sands in front of the sea wall south of the pier were converted into the Marine Gardens,[88] a lawn with trees and hedges.[89] The undeveloped lands north of Scarbrough Avenue were fenced in and planted with trees in a space called The Park.[88][90] This stagnation coincided with a declining number of day-trippers, which fell from a peak of 230,277 in 1882 to 118,473 in 1885.[88] The local historian Richard Gurnham could not find a clear explanation for this decline in contemporary reports, though one newspaper article from 1884 blamed "the depression of trade" in Nottingham for a fall in visitor numbers compared with the previous year.[88]

1890s to 1945: boom years

Fortunes changed during the 1890s;[91][92] in the words of the historian Susan Barton, "Skegness and other 'lower' status resorts provided cheap amusements, beach entertainers, street traders and, by the end of the nineteenth century, spectacular entertainment for a mass market".[93] Convalescent homes began opening in the town, the earliest being the Nottinghamshire Convalescent Home for Men (1891). Holiday homes or camps for the poor opened in 1891 and 1907.[94][95] The town became an urban district in 1895.[96] In 1908 the famous "Jolly Fisherman" poster was used by GNR to advertise day trips from King's Cross in London.[97] By 1913 more than 750,000 people made excursions to the town.[97] Aside from bathing and enjoying the sands, visitors to Skegness found entertainment in the pier, which had a concert hall, saloon and theatre. Other theatres and picture houses opened in the early 20th century.[98][99] Britain's first switchback railway had opened in the town in 1885 or 1887.[n 7] A fairground operated on the central beach before the First World War and the Figure 8 roller coaster replaced the switchback in 1908.[102][89] By 1911, the population had reached 3,775.[103]

Seventy-one local servicemen who died in the First World War are commemorated on the town's war memorial.[104] Aside from a seaplane base briefly established by the town in 1914, the conflict brought little change to the fabric of Skegness.[105] Its popularity as a tourist destination grew in the interwar years and boomed during the 1930s.[106][107] The urban district council purchased the seafront in 1922 and its surveyor R. H. Jenkins oversaw the construction of Tower Esplanade (1923), the boating lake (1924, extended in 1932), the Fairy Dell paddling pool, and the Embassy Ballroom and an outdoor pool in 1928, and remodelled the foreshore north of the pier in 1931. Billy Butlin (who had been a stall holder on the beach since 1925) built permanent amusements south of the pier in 1929.[89][108] In 1932 the first illuminations were turned on and the following year Butlin launched a carnival. Cinemas and casinos joined the theatres of the Edwardian period as popular attractions, while some of the apartments and houses by the seafront were converted into shops, cafés and arcades. In 1936, Butlin built his own all-in holiday camp in Ingoldmells, providing constant entertainment and facilities for guests.[109] It was joined in 1939 by The Derbyshire Miners' Holiday Camp.[110] This coincided with growth in the residential area, mostly speculative developments and some council housing;[n 8] North Parade was built up with hotels in the 1930s[89] and the Seathorne Estate was also laid out in 1925.[113] By 1931, the town's population had reached 9,122.[114]

During the Second World War, the Royal Air Force billeted thousands of trainees in the town for its No. 11 Recruit Centre. The Butlin's camp was occupied by the Royal Navy, who called it HMS Royal Arthur and used it for training seamen. Aerial bombing of the town began in 1940; there were fatalities on several occasions, the greatest being on 24 October 1941 when twelve residents were killed during a bombing raid.[115] Fifty-seven local servicemen died in the conflict and are named on the town's war memorial.[104]

Since the Second World War

Since the Second World War, self-catered holidays have become popular, prompting the growth of caravan parks and chalet accommodation. By 1981, 20 caravan sites were in operation and five years later there were over 100,000 holiday caravans and chalets in Skegness and Ingoldmells.[116][117] Increasingly the lodging accommodation in the town centre closed as a result, or was converted into flats or shops.[116] The 1970s also witnessed the advent of the cheap package airline holiday abroad, which took visitors away from British seaside towns.[118] The decline in coal mining in the East Midlands in the 1980s caused what the BBC described as a "damaging dip in trade".[119] Nevertheless, holiday-makers continued to visit the town and, in the 1980s and 1990s, people ventured to Skegness for their second holiday alongside trips abroad;[118] it also proved popular among the elderly in the winter months.[119] The resort's popularity grew during the late 2000s Great Recession, as it offered a cheaper alternative to holidays abroad.[120] Between 2006 and 2008, 870,000 people made overnight trips to Skegness; this figure had risen to 1,030,000 for 2010–12.[121]

The fabric of the town centre has also changed. North and South Bracing were built in 1948–49. Butlin's left the main amusement park and it was extensively refurbished by Botton Bros in 1966; the switchback on North Parade was demolished in 1970.[117] Residential development has included council estates near St Clement's Church and Winthorpe,[122] as well as private developments in various locations around the town.[123] The seafront was fully developed in the 1970s and the last of The Park built on in 1982.[124] In 1971, the pier entrance was remodelled;[98] seven years later, a large section was swept away in a storm.[125] The Embassy Ballroom and the swimming baths were replaced in 1999 with the Embassy Theatre Complex, which includes a theatre, indoor swimming pool, leisure centre and car park.[89] By 2001, European Union grants had provided millions of pounds towards regeneration schemes.[119] Since the war, most of the seafront's hotels, cinemas and theatres have been turned into amusement arcades, nightclubs, shops and bingo halls.[126] What remained of Frederica Terrace, one of Skegness's oldest buildings, had been converted into entertainment bars and arcades before it was destroyed in a fire in 2007.[127][128]

Economy

According to VisitEngland, in 2011 Skegness was the fourth most popular holiday destination in England among UK residents.[129] In 2015, Skegness and Ingoldmells received 1,484,000 visitors, of which 649,000 were day visitors; this brought in £212.83 million in direct expenditure, with an estimated economic impact of £289.60 million.[130] The town council has described local employment as "heavily reliant" on tourism.[131] One estimate suggested that in 2015 2,846 jobs were supported directly by the visitor economy (accounting for around a third of the town's employed residents), with tourism indirectly supporting nearly 900 more.[130][132] Over half of these jobs were in accommodation and food and drink, with a further 18.1% in retail.[130] Skegness's visitor economy has been described by the district council as "counter-cyclical"; while continuing to serve a loyal client base, it provides a cheap alternative to holidays abroad and has therefore proven popular when the economy has been slower for the rest of the region.[120] The seafront is a hub for the tourism industry, much of which is geared towards the provision of food (most famously fish and chips), amusement arcades and other attractions, including the Botton's Pleasure Beach funfair with various rides. The pubs, bars and nightclubs, and neon-lit amusements have earned it the popular nickname "Skegvegas" (after Las Vegas).[133]

Before the 1950s, the only major manufacturing interest in Skegness was Alfred Hayward's rock factory which had opened in the 1920s. After the Second World War, some other light industry arrived, including Murphy Radio and the nylon makers Stiebels;[122] in 1954 the bearings and packaging systems manufacturer Rose Brothers (Gainsborough) Ltd opened a factory in the town, on Church Road in a former laundry.[134][135] The urban district council opened an industrial estate off Wainfleet Road in 1956 which Murphy and Stiebels moved to. Murphy's successor left the town in the 1970s, but Stiebels and the ride manufacturer R. G. Mitchell were still operating on the estate in the late 1980s, while Rose-Forgrove (which had opened a larger factory in 1977) and Sanderson Forklifts had factories elsewhere in the town.[122][134] The latter went into administration in 1990,[136] and the Rose Bearings factory was sold to NMB-Minebea in 1992;[137] they closed it in 2010.[138] The ride manufacturer R. G. Mitchell was purchased in 2005 by Photo-Me International; operation resumed under the name Jolly Roger Amusement Rides,[139] which continues to operate on the industrial estate as of 2020.[140] According to Google Maps, in 2020 there were three other manufacturers operating on the industrial estate: Unique Car Mats (UK) Ltd (founded in 1989), Windale Furnishings Ltd (a caravan seating maker founded in 1993), and Parragon Rubber Company.[140][141][142][143] A range of services have outlets on the estate, including a medical practice, two skilled trades, a solicitor, five vehicle repair garages, three other repair services and a mobile disco service. There is also a recycling centre and driving test centre; 16 shops ranging from a cheesemonger to tyre dealers; 12 wholesalers operating in electrics, building materials, plumbing and hardware supply, and 11 other wholesalers in fields including clothing, restaurant equipment, meat and plastic sheeting.[140] The district council have proposed extending the estate as of 2016. The council also opened the Aura Skegness Business Centre there in 2004.[144]

Along with Louth, Skegness is "one of the main shopping and commercial centres" in East Lindsey, most likely due to it being the closest service hub for a large part of the surrounding rural area.[145] Management Horizon Europe's 2008 UK shopping index measured the presence of national suppliers; Skegness was the highest ranked shopping destination in the district. It also ranked highest in the 2013–14 Venuescore survey.[146] The High Street and Lumley Road are key retail areas,[147] along with the Hildreds Centre (a small shopping mall which opened in 1988),[148] Skegness Retail Park (developed between 2000 and 2005),[149] and the Quora Retail Park on Burgh Road which opened in 2017 and includes several supermarkets;[150][151] other supermarkets operate elsewhere.[152][n 9] Occupancy rates are relatively high: in 2015, 4% of ground-floor retail units were vacant, which is less than half the national average and down from 9% in 2009.[157] Nevertheless, Skegness is relatively weak at offering higher value comparison goods, with Lincoln and Grimsby being key destinations for high-value shopping.[145]

Demography

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: [158] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Population change

The poll tax returns for 1377 recorded 140 people living in Skegness over the age of 14; in 1563 there were 14 households, and in the late 17th century there were ten families.[159] The first census of the parish was conducted in 1801 and recorded a population of 134. It had risen above 300 by 1841 and reached 366 ten years later, before dropping back to 349 in 1871. Following the initial development of the seaside resort, the population rose rapidly,[59] contracted in the 1880s[88] and then rose sharply so that by 1921 the resident population was over 9,000. This figure reached 12,539 in 1951, and continued to rise at varying rates over the course of the century. It had reached 18,910 in 2001 and 19,579 in the most recent census, taken in 2011.[158] As designated by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the Skegness built-up area incorporates the contiguous conurbation extending north through Ingoldmells to Chapel St Leonards; this had a population of 24,876 in 2011 which makes it the largest settlement in the East Lindsey district (followed by Louth)[160] and represents about 18% of the district's population.[161]

Ethnicity and religion

According to the 2011 census, Skegness's population was 97.6% white; 1% Asian or British Asian; 0.4% Black, African, Caribbean or Black British; and 0.9% mixed or mutli-ethnic; and 0.1% other. The population is therefore less ethnically diverse than England as a whole, which is 85.4% white; 7.8% Asian or Asian British; 3.5% Black, African, Caribbean or Black British; 2.3% mixed ethnicities; and 1% other. 94.2% of the town's population were born in the United Kingdom, compared with 86.2% nationally; 3.5% were born in European Union countries other than the UK and Ireland, of which more than three quarters (2.7% of the total) were born in post-2001 accession states; for England, the figures were 3.7% and 2.0% respectively. 1.8% of the population was born outside the EU, whereas the total for England was 9.4%.[162][163]

In the 2011 census, 68.2% of Skegness's population said they were religious and 24.9% said they did not follow a religion, very similar to England as a whole (68.1% and 24.7% respectively). However, compared to England's population, Christians were a higher proportion of the Skegness population (66.8%), and all other groups were present at a lower proportion than the national rates. There were 8 Sikhs in Skegness, making up a negligible proportion of the population compared with 0.8% nationally; Hindus composed 0.1% (compared with 1.5% in England), Muslims 0.5% against 5% nationally, Jewish people 0.1% compared with 0.5% for all of England, and Buddhists 0.2% of the town's population, contrasting with 0.5% nationally.[162][163]

| Ethnicity, nationality and religious affiliation of residents (2011)[162][163] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Asian or British Asian | Black, African, Caribbean or Black British | Mixed or multi-ethnic | Other ethnicity | Born in UK | Born in EU (except UK and Ireland) | Born outside EU | Religious | Did not follow a religion | Christian | Muslim | Other religions | |

| Skegness | 97.6% | 1.0% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 0.1% | 94.2% | 3.5% | 1.8% | 68.2% | 24.9% | 66.8% | 0.5% | 0.4% |

| England | 85.4% | 7.8% | 3.5% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 86.2% | 3.7% | 9.4% | 68.1% | 24.7% | 59.4% | 5.0% | 2.5% |

Household composition, age, health and housing

| Gender, age, health and household characteristics (2011)[162][163] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Skegness | England |

| Male | 47.8% | 49.2% |

| Female | 52.2% | 50.8% |

| Married[n 11] | 45.3% | 46.6% |

| Single[n 11] | 28.8% | 34.6% |

| Divorced[n 11] | 12.8% | 9.0% |

| Widowed[n 11] | 10.3% | 6.9% |

| One-person households | 35.9% | 30.2% |

| One-family households | 58.1% | 61.8% |

| Mean age | 44.3 | 39.3 |

| Median age | 46.0 | 39.0 |

| Population under 20 | 21.0% | 24.0% |

| Population over 60 | 32.2% | 22.0% |

| Residents in good health | 69.6% | 81.4% |

| Owner-occupiers[n 12] | 54.7% | 63.3% |

| Private renters[n 12] | 27.5% | 16.8% |

| Social renters[n 12] | 15.7% | 17.7% |

| Living in a detached house[n 12] | 32.4% | 22.3% |

In the 2011 census, 47.8% of the population were male and 52.2% female. Of the population over 16, 45.3% were married, compared to 46.6% in England; 28.8% were single (a smaller proportion than in England where it is 34.6%), 12.8% divorced (compared with 9% in England), 10.3% widowed (higher than the 6.9% for all of England), 2.6% separated and 0.2% in same-sex civil partnerships (2.7% and 0.2% respectively in England). In 2011, there were 9,003 households in Skegness civil parish. It has a slightly higher than average proportion of one-person households (35.9% compared with England's figure of 30.2%); most other households consist of one family (58.1% of the total, compared with 61.8% in England). There are higher than average rates of one-person (16.8%) and one-family (10.8%) households aged over 65 (the figures for England are 12.4% and 8.1% respectively).[162][163] In 2016, East Lindsey had Lincolnshire's second-highest rate of conception among females aged 15 to 17 (28.7 per 1,000).[164]

East Lindsey has a high proportion of elderly people living in the district, driven partly by high in-migration and by the out-migration of younger residents; the local authority has described this as a "demographic imbalance".[165] A 2005 study by the town council reported that for every two people aged 16–24 who left the town, three people aged 60 or above moved in.[131] The 2011 census showed Skegness's population to be older than the national average; the mean age was 44.3 and the median 46 years, compared with 39.3 and 39 for England. 21% of the population was under 20, versus 24% of England's, and 32.2% of Skegness's population was aged over 60, compared with 22% of England's population.[162][163] This high proportion of elderly residents has increased the proportion of infirm people in the district.[165] In 2011, 69.6% of the population were in good or very good health, compared to 81.4% in England, and 9.9% in very bad or bad health, against 5.4% for England. 28.6% of people (12.8% in 16–64 year-olds) also reported having their day-to-day activities limited, compared with 17.6% in England (8.2% in 16–64 year-olds).[162][163]

As of 2011, Skegness has a lower proportion of people who own their homes with or without a mortgage (54.7%) than in England (63.3%), a greater proportion of people who privately rent (27.5% compared with 16.8%) and a slightly smaller proportion of social renters (15.7% compared with 17.7% nationally). The proportion of household spaces which are detached houses is higher than average (32.4% compared with 22.3%), as is the proportion which are apartments in a converted house (9.8% compared with 4.3%) and flats in a commercial building (2.2% compared with 1.1%). The proportion of terraced household spaces is much lower (8.9% against 24.5% nationally), while the proportion of purpose-built flats is also lower (14% versus 16.7%). 2.3% of household spaces are caravans or other mobile structures, compared with 0.4% nationally.[162][163] Since the end the 20th century, a growing number of people have opted to live in static caravans for a large part of the year; a 2011 report estimated that 6,600 people (mostly older and from former factory cities in the Midlands) were living in such properties in Skegness.[166]

Workforce and deprivation

| Economic characteristics of residents aged 16 to 74 (2011)[162][163] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Skegness | England |

| Economic activity | ||

| Economically active | 60.0% | 69.9% |

| Employed | 51.7% | 62.1% |

| Full-time employed | 27.7% | 38.6% |

| Retirees | 21.7% | 13.7% |

| Long-term sick or disabled | 7.9% | 4.0% |

| Long-term unemployed | 2.3% | 1.7% |

| Industry | ||

| Manufacturing | 7.1% | 8.8% |

| Construction | 6.9% | 7.7% |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of vehicles | 21.2% | 15.9% |

| Transport and storage | 4.3% | 5.0% |

| Accommodation and food services | 17.3% | 5.6% |

| Information and communication | 0.6% | 4.1% |

| Financial and insurance | 0.8% | 4.4% |

| Professional, scientific and technical | 2.8% | 6.7% |

| Public administration and defence | 3.6% | 5.9% |

| Education | 7.3% | 9.9% |

| Health and social work | 11.7% | 12.4% |

| Occupation | ||

| Managers and directors | 12.9% | 10.9% |

| Professionals; associate professionals | 13.9% | 30.3% |

| Administrative and secretarial | 8.4% | 11.5% |

| Sales and customer services | 12.1% | 8.4% |

| Caring, leisure and other services | 12.2% | 9.3% |

| Skilled trades | 12.9% | 11.4% |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 8.9% | 7.2% |

| Elementary occupations | 18.9% | 11.1% |

| Qualifications | ||

| No qualifications | 40.8% | 22.5% |

| Level 4 or higher | 10.7% | 27.4% |

In 2011, 60% of Skegness's residents aged between 16 and 74 were economically active, compared with 69.9% for all of England. 51.7% were in employment, compared with 62.1% nationally. The proportion in full-time employment is also comparatively low, at 27.7% (against 38.6% for England). The proportion of retirees is higher, at 21.7% compared with 13.7% for England. The proportion of long-term sick or disabled is 7.9%, nearly double England's 4%; 2.3% of people were long-term unemployed, compared with 1.7% in all of England. The 2011 census revealed that the most common industry residents worked in were: wholesale and retail trade and repair of motor vehicles (21.2%), accommodation and food services (17.3%), and human health and social work (11.7%). The proportion of people employed in accommodation and food services was over three times the national figure (5.6%), while the proportion working in wholesale and retail trade and vehicle repair was also higher than in England as a whole (15.9%). Most other industries were under-represented comparatively, with both financial services (0.8% versus 4.4% nationally) and information and communication (0.6% against 4.1% nationally) especially so.[162][163]

The tourism industry in Skegness is dominated by low-paid, low-skilled and seasonal work.[167] Compared with the whole of England, the workforce has a relatively high proportion of people in elementary occupations (18.9%), sales and customer service occupations (12.1%), caring, leisure and other service occupations (12.2%), as well as skilled trades (12.9%), managers and directors (12.9%) and process plant and machine operatives (8.7%). There is a much lower proportion of people in professional, associate professional, technical, administrative and secretarial occupations than in England as a whole (combined 22.3% versus 41.7% of England's population aged 16–74).[162][163]

A lack of more varied, higher skilled and better paid work and further education opportunities leads many more skilled, ambitious or qualified young people to leave. There is a chronic difficulty in attracting professionals to the area, including teachers and doctors; this is partly due to the perceived remoteness of the area, seasonality and social exclusion.[131][167] Skegess's poor transport links with other towns and limited public transport have also been identified by consultants as a "barrier" to economic growth, diversification, investment and commutability. While the digital nature of the information technology sector could provide opportunities for growth, weak broadband has stymied this sector's development in the town.[168] Employers also find it difficult to attract higher skilled workers, including chefs; a report prepared for the town council cites a lack of "work readiness" among young people as a common problem facing employers.[169] The proportion of residents aged 16 to 74 with no qualifications was 40.8%, much higher than the national figure (22.5%); the proportion of residents whose highest qualification is at Level 1, 2 or 3 (equivalent to GCSEs or A-Levels) is lower in each category than the national population; 10.7% of the population have a qualification at Level 4 (Certificate of Higher Education) or above, compared with 27.4% nationally.[162][163]

In a 2013 ONS study of 57 English seaside resorts, Skegness and Ingoldmells (combined) was the most deprived seaside town; 61.5% of their statistical areas (LSOAs) were in the most deprived quintile nationally; only 7.7% fell in the least-deprived three quintiles.[170] The government's Indices of Multiple Deprivation (2019) place large parts of Skegness among the 10% most deprived parts of England;[171] two of its neighbourhoods were ranked among the ten most deprived areas in Lincolnshire.[172] There is limited research into the causes of deprivation in the town.[167] A local official quoted by The Guardian in 2013 attributed high levels of deprivation to the seasonal and low-paid nature of work in the tourism industry, which constitutes a large part of Skegness's economy; and also the tendency for retirees (often in variable health) from former industrial areas in the East Midlands to move to the town and spend most of the year living there in caravans.[173] In 2019, the town council listed several key challenges: the low-paid, low-skilled and seasonal nature of work in the tourism industry; a consequential dependency on benefits and a reduced tax base; the under-funding of public services; poor infrastructure; a lack of training for and consequent out-migration of talented young people; and difficulty attracting skilled workers.[167]

Transport

Road

The A52 road from Newcastle-under-Lyme to Mablethorpe passes through Skegness via Nottingham, Grantham and Boston. The A158 from Lincoln terminates in the town. The A1028 connects Skegness with the A16, which runs from Grimsby to Peterborough via Louth.[174]

Bus

Omnibus services reached the village from Boston before the development of the resort;[63] by the 1840s, Brown's omnibus made the journey from Boston three days a week.[175] As of 2020, Stagecoach Lincolnshire is the main bus operator in the town with regular services on routes to Ingoldmells and Chapel St Leonards;[176] there are Lincolnshire InterConnect services up the coast as far as Mablethorpe and inland to Boston and Lincoln.[177]

Railway

Skegness railway station is the terminus for the Grantham to Skegness ("Poacher") line which runs hourly services from Nottingham via Grantham.[178] Opened in 1873, it was the final station on the Firsby–Skegness branch of the East Lincolnshire Railway.[179] The number of people travelling by car and coach probably overtook the number using the train in the 1930s, a trend solidified in the post-war years. The station was earmarked for closure in the Beeching cuts in the 1960s, but a third of the summer visitors still used it and lobbying by the urban district council preserved passenger services. The line was nevertheless closed to freight traffic in 1966 and the main interconnecting line, the East Lincolnshire Railway, was dismantled from Firsby to Grimsby in 1970. The passenger timetable was reduced to save costs in 1977, but a full timetable returned in 1989 and improvement works were carried out in 2001 and 2011; the latter seeing the old station master's house demolished.[180] As of 2020, trains run the full length of the Poacher Line and the Nottingham to Grantham Line to give connections to the East Midlands; Nottingham, Grantham, Boston and Sleaford have direct connections, while Leicester, Derby and Kettering require a change at Nottingham.[181][182]

Air

Skegness Water Leisure Park, north of the town, has its own light aircraft airfield named Skegness Airfield (ICAO: EGNI), operated by Skegness Aerofield Club. It is equipped with two runways, and PPR (Prior Permission Required) is required for landing.[183] The main international airport serving Skegness is East Midlands Airport at Castle Donington, 14 miles (23 km) south of Nottingham and approximately 90 miles (140 km) from Skegness. Humberside Airport, near Immingham in North Lincolnshire, is approximately 48 miles (77 km) away, but operates a much smaller range of passenger services.

Government and politics

Local government

Lying within the historic county boundaries of Lincolnshire since the Middle Ages, the ancient parish of Skegness was in the Marsh division of the ancient wapentake of Candleshoe in the Parts of Lindsey.[184][185] In 1875, it was placed in the Spilsby Poor Law Union, but in 1885 Skegness became a local board of health and urban sanitary district. In 1894, Skegness Urban District was created in its place.[184][186] The civil parish of Winthorpe – which had previously been part of the Spilsby union, rural sanitary district and, from 1894, rural district – was abolished in 1926; most of it was merged into Skegness Urban District and a portion into Addlethorpe civil parish.[187][188] In 1974, the urban district was merged with the municipal borough of Louth, the Alford, Horncastle, Mablethorpe and Sutton, and Woodhall Spa urban districts, and the rural districts of Horncastle, Louth and Spilsby to create East Lindsey, a district of Lincolnshire;[189] by statutory instrument Skegness civil parish became the urban district's successor.[190]

Skegness Town Council, the parish-level government body beneath the district council, is composed of 21 councillors from four wards: Clock Tower (1 seat), St Clements (7 seats), Winthorpe (5 seats) and Woodlands (8 seats). There are seven representatives for Skegness on East Lindsey District Council, which uses different wards: three councillors are returned for Scarbrough and Seacroft ward, and two each from St Clements and Winthorpe wards. Skegness sends two councillors to Lincolnshire County Council, one each for Skegness North and Skegness South divisions.[191]

Skegness Urban District Council meetings were held at 23 Algitha Road until 1920, when the authority purchased the Earl of Scarbrough's estate office at Roman Bank for £3,000 and used those as offices; these burned down in 1928; a new town hall opened in 1931 and was later extended. In the 1950s, the council acquired for £50,000 the former convalescent home run by the National Deposit Friendly Society on North Parade (this had been built in 1927); this was converted into offices, which were opened in 1964.[192] The town council took over the building and it continues as the town hall as of 2019.[193]

National and European politics

In national politics, Skegness fell within the Lincolnshire parliamentary constituency until 1832; in 1818 four residents were entitled to vote, and in 1832 there were seven electors.[194] That year the county was divided up and the village was included (with all of Lindsey) in North Lincolnshire.[195] In 1867, it was transferred to the new Mid Lincolnshire constituency, which was abolished in 1885, after which Skegness was placed in the Horncastle constituency.[196] Another reorganisation saw the parish incorporated into the East Lindsey seat in 1983;[197] this was abolished in 1995 and Skegness was transferred into the new constituency of Boston and Skegness.[198] The current constituency has been held by Conservative members of parliament since it was created;[n 13] the incumbent is Matt Warman, who has held it since 2015.[201] Between 1999 and the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union (EU) in 2020, Skegness was represented in the European Parliament by the East Midlands constituency.[202]

At the first election after it was created (1997), the current seat was highly marginal,[203] with the Conservatives receiving 42.4% of the vote and Labour 41.0%.[204] By 2019 the Conservatives had increased their vote share to 76.7% (their second-highest nationally),[205] while Labour's share had fallen to 14.0%.[206]

The same period saw support for the Eurosceptic UK Independence Party (UKIP) grow, reaching a peak in 2015, when it polled second and secured UKIP's second-highest vote share in any constituency in that election.[207] The constituency is estimated to have had the highest vote share in favour of leaving the EU in the 2016 EU referendum, at 75.6%.[208] In the aftermath the town became the focus of international media attention,[209][210] with Reuters labelling it "Brexit-on-Sea" and suggesting that many of its residents were "more nostalgic and more socially conservative" than those in diverse, liberal, urban areas, and keen to see state funds paid to the EU redirected into supporting the town.[211] Afterwards support for UKIP fell and the party did not stand in 2019,[206] although support for leaving the EU remained high.[211] The Brexit Party did not contest the parliamentary seat in 2019,[206] but in the European Parliament elections held earlier that year, it has been estimated that Boston and Skegness probably had the third-highest vote share for the Brexit Party of any constituency.[212]

Public services

Utilities and communications

As part of the Earl of Scarbrough's scheme, gas works were opened in the town in 1877 and were lighting the streets the following year.[90] The urban district council (UDC) declined to purchase the gas company in 1902; the UDC attempted to take it over in 1911, and (after much dispute with the company) purchased it in 1914.[213] The works were extended in the 1920s.[214] The UDC's gas company was nationalised in 1949 and its functions taken over by the East Midlands Gas Board,[213] which merged into British Gas Corporation in 1973 and was privatised in 1986.[215]

The town's water works opened in 1879[216] and were extended in the 1920s.[214] To meet growing demand, Lord Scarbrough had a new borehole sunk at Welton le Marsh in 1904, with a pumping station and pipes which transported fresh water to the town; the water company was purchased by Skegness Urban District Council in 1909.[217][218] The first sewerage disposal system was designed by D. Balfour as part of the Earl of Scarbrough's development scheme; a sewerage farm and works were erected at Seacroft. The development was principally funded by the Earl, with a quarter of the funds contributed by the Spilsby Sanitary Authority.[90] A sewerage disposal works opened at Burgh Le Marsh in 1936.[214] Responsibility for water was later taken over by the East Lincolnshire Water Board; in 1973 this merged into the Anglian Water Authority,[219] which was privatised as Anglian Water in 1989.[220]

The Mid-Lincolnshire Electricity Supply Company brought electricity to the town in 1932.[221] The company was nationalised in 1948 and its function taken over by the East Midlands Electricity Board.[222] Street lighting was electrified in the late 1950s.[221] Electricity supply was privatised in 1990.[223]

Skegness's first post office opened in 1870; it moved premises in 1888 and 1905, before moving to Roman Bank in 1929.[111] As of 2020, Royal Mail's Skegness Delivery Office operates there;[224] Post Offices also operate on Burgh Road and Drummond Road in Skegness, and at Winthorpe Avenue in Seathorne.[225] A wireless telegraph station operated at Winthorpe from 1926 to 1939.[111] Lincolnshire County Library Service opened a branch in 1929 which was run by volunteers. In the 1930s, the council purchased a former shop on Roman Bank and converted it into the current library, run by full-time staff.[214] As of 2020[update], it opens every day except Sunday.[226]

Emergency services and justice

In 1827 the village was afforded its first police constable, which it shared with Ingoldmells.[227] The town's first police station opened in 1883 on Roman Bank.[228] In 1932, Skegness became a divisional police headquarters. Its current building opened in 1975. Criminal cases were heard in Spilsby until Skegness was granted its own petty sessions in 1908; these operated only during summer until 1929, when cases were heard there year-round; a court opened on Roman Bank that year. The building was replaced in 1975 and the Spilsby magistrates court closed in 1980, transferring all cases to Skegness.[111] By 1913, the town had a fire brigade.[229] A station was added to the Town Hall on the corner of Roman Bank and Algitha Road in the late 1920s. A new station was built on Churchill Avenue in 1973.[194] It continues to operate as of 2020.

Skegness had a signal station by 1812 and four years later a mortar-fired brass lifeline was put in place in the village. In 1825, a lifeboat was purchased for Wainfleet Haven and first launched from Gibraltar Point in 1827; it moved to Skegness in 1830. A new boathouse was built in 1864 on South Parade and rebuilt in 1892. Motorised tractors were used to pull the boats after 1926 and the last sailing boat was retired four years later.[230] The current lifeboat station was built in 1990.[231]

Healthcare

Skegness and District General Hospital opened in 1913 as a cottage hospital; it underwent major redevelopment works in 1939, was taken over by the National Health Service nine years later and extended in 1985.[232] As of June 2020, it is a community hospital run by the Lincolnshire Community Health Services NHS Trust;[233] some of its services are provided by the United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust (ULH). It contains two in-patient wards, with 39 beds (including three in palliative care) and its services include a 24-hour, walk-in Urgent Care Centre.[234] ULH runs Accident and Emergency departments at Lincoln County Hospital and Pilgrim Hospital in Boston.[235] As of 2020, the town has two GP practices (on Hawthorn Road and Churchill Avenue),[236] four dental practices (three on Algitha Road and one on Ida Road),[237] and three opticians.[238] There are community mental health services provided at Holly Lodge.[239] There is a health centre on Cecil Avenue[240] and the hospital includes a contraception and general health advice centre.[241]

Education

Skegness's first elementary school was established in 1839. Winthorpe's first schoolhouse opened in 1865.[242] As part of Lord Scarbrough's town plan, Skegness National School opened on Roman Bank in 1880; in 1932 it was replaced with another elementary school, Skegness Senior Council School, which existed until it became a secondary modern school in the 1940s.[243][244] The county-council run Infants' School was founded on Cavendish Road in 1908, followed by Skegness County Junior School in 1935 (renamed Skegness Junior School in 1999), the Seathorne Junior School in 1951 (replacing the Winthorpe School which closed) and Richmond Junior School in 1976.[243][245][246][247] As of 2020, the town is served by five coeducational state primary schools, four of which are academies: the Skegness Infant Academy (established when the infant school became an academy in 2012);[248] Skegness Junior Academy (which replaced the Junior School in 2012);[249] Seathorne Primary Academy (which replaced Seathorne Primary School in 2019);[250] The Richmond School;[251] and Beacon Primary Academy (opened as a new school in 2014).[252] As of 2020, one private primary school operates in the town: The Viking School, which opened in 1982.[253]

Before 1933, the only secondary education available to Skegness's children was at Magdalen College School, a grammar school in Wainfleet. In 1933, it closed and was replaced by the coeducational Skegness Grammar School, which opened in the town[243] and continues to select pupils using the eleven-plus examination; it provides boarding facilities for pupils who do not live locally. Having previously been grant-maintained and a foundation status school, Skegness Grammar School converted to an academy in 2012. At its last Ofsted inspection report in 2017, it was assessed as "requiring improvement". As of 2020, there are 456 pupils on the roll, out of a capacity of 898.[254][255][256] The passage of the Education Act 1944 made secondary education compulsory for pupils aged 11–15 from 1945.[257] The Skegness Secondary Modern School opened as a result; it was renamed the Lumley Secondary Modern School in 1956. Another school, the Morris Secondary Modern, opened in 1955. They merged in 1986 to form the Earl of Scarbrough School,[244] which closed in 2004 and reopened as St Clements College, a community school which converted into Skegness Academy in 2010.[258][259] It is coeducational and has a sixth form; at its 2020 Ofsted inspection, it was assessed as "requiring improvement". There were 893 pupils on roll in that year, out of a capacity of 1,340.[260]

Both of the secondary schools provide education for pupils aged 16–18.[255][260] Other providers of further education include the Skegness College of Vocational Training (a private centre founded in 1975);[261][262] First College, which formed in 2000 following a merger of the East Lindsey Information Technology Centre (East Lindsey ITeC) which had opened in Skegness in 1984;[263][264] and the Skegness TEC, which in 2017 replaced the Lincolnshire Regional College in Skegness (founded in 2009).[265]

Religious sites

The three Anglican places of worship are the churches of St Clement and St Matthew in Skegness, and St Mary's Church in Winthorpe. St Clement's and St Mary's have medieval origins. When the seaside resort was being planned in the 1870s, St Clement's was too small and far from the new town so the much larger St Matthew's Church was built on Scarbrough Avenue and consecrated in 1885.[266][n 14] As of 2020, services are usually held every Sunday in St Matthew's, and in St Mary's and St Clement's on all but the first Sunday of the month.[270] The parishes of Skegness and Winthorpe were united in 1978;[269] its legal name is Skegness with Winthorpe.[271] The parish forms part of the Skegness Group, which includes the parishes of Ingoldmells and Addlethorpe.[272] It is in the Calcewaithe and Candleshoe rural deanery in the archdeaconry and diocese of Lincoln.[271][273][n 15]

Skegness also has a Roman Catholic church, the Church of the Sacred Heart on Grosvenor Road;[274] it has been based there since 1950, having previously occupied the town's first purpose-built Catholic church since 1898.[275]

There are several non-conformist places of worship. As of 2020, Skegness Methodist Chapel on Algitha Road holds services on Sundays and mid-morning prayers on Mondays.[276][n 16] St Paul's Baptist Church also holds regular Sunday services.[279][n 17] The Salvation Army has had a unit in the town since 1913 and built its citadel on the High Street in 1929;[281] it remains in use as of 2020.[282] The Assemblies of God Pentecostal Church was registered as a charity in 1996; it later changed its name to the New Day Christian Centre[283] and moved to new premises in 2011;[284] as of 2020 it operates on North Parade as The Storehouse Church and, as well as running church services, provides Skegness's only food bank.[283][285] As of 2020, there is a seventh-day adventist church on Philip Grove.[286]

In 2019, East Lindsey Council approved plans for a mosque and community centre on Roman Bank.[287]

Culture

Visitor attractions

The Rough Guides describe Skegness as "every inch the traditional English seaside town".[288] Its long, wide, sandy beach is a main attraction for visitors;[288] described as "sparklingly clean" by Rough Guides,[288] in 2019 it was re-awarded the Foundation for Environmental Education's Blue Flag award which recognises the beach's high-quality water, facilities, beach safety, management and environmental education facilities.[289] Between 1 May and 30 September, dogs are banned from the beach.[290] Donkey rides are offered for children there.[291]

The seafront includes Skegness Pier, which houses amusements;[292] to the south, Botton's Pleasure Beach is a funfair with roller coasters and other rides.[133] Further south still is the Jubilee Clock Tower and the boating lake and Fairy Dell paddling pool.[293] The western side of Grand Parade houses amusements and eateries,[288][133] punctuated by the entrance to Tower Gardens, a park; its pavilion, which dated to 1879, was demolished in 2019–20 and a community centre and café built on its site.[294] Opposite the gardens is the Embassy Theatre.[293] The town's nightlife includes bars, pubs and nightclubs.[133]

Natureland Seal Sanctuary, on North Parade, rescues and houses distressed seals; it also features penguins, aquariums, and other animals.[295] The town has an aquarium (Skegness Aquarium), which opened on Tower Esplanade in 2015.[296] Further into the town, The Village Church Farm (formerly Church Farm Museum) contains exhibitions about historical farming life.[297] A volunteer-run heritage railway, the Lincolnshire Coast Light Railway, moved to Skegness in 1990 and opened to fare-paying members of the public in 2009; it operates along a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) length of track.[298]

To the south of Skegness is Gibraltar Point, a national nature reserve, consisting of unspoilt marshland. It was among England's earliest bird observatories when it was established in 1949 and, as of 2020, is open to the public. Alongside walkways and paths, it has a visitor centre, café and toilet facilities.[299]

Arts and music

Skegness Carnival normally operates as an annual event (in August) as of 2020;[300] the town hosted its first carnival in 1898, but the modern event dates to 1933.[106] Since 2009, Skegness has held a music, art and cultural event, the SO Festival;[301] in 2013 the district council estimated that it generated £1m for the area.[302] In 1928, as part of the local authority's foreshore development, the Embassy Ballroom was built on Grand Parade. It was remodelled in 1982 and completely rebuilt in 1999 as the Embassy Theatre Complex,[89] which is Skegness's only theatre as of 2020.[303][n 18] The town has two cinemas: the Tower Cinema (opened in 1922) and an ABC Cinema (opened in 1936), as of 2020.[307][308][n 19]

The Skegness Boys' Brigade Band started in 1908; it was disbanded on the outbreak of the First World War. A new band was formed in 1923 or 1928, as Skegness Town Band, which later changed its name to Skegness Silver Band.[312][313] The band continues to operate as of 2020.[314] The Skegness Excelsior Band also operated in the interwar period.[106] The town's amateur dramatic society, the Skegness Playgoers, was founded in 1937. As of 2020, they aim to put on two productions a year at the Embassy Theatre.[315]

Sport

Skegness is home to Skegness Town A.F.C., which plays at the Vertigo Stadium on Wainfleet Road; known as The Lilywhites, the club was founded in 1947 and has been in the Northern Counties East Football League since 2018.[316] Another team, Skegness United F.C., folded in 2018.[317] The town has a rugby club, Skegness R.U.F.C., which plays in the Midlands 4 East (North) division of the Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Derbyshire Rugby Football Union, and has a clubhouse on Wainfleet Road.[318] Skegness Cricket Club traces its origins to at least 1877 and has its ground on Richmond Drive.[319] There is also the Skegness Yacht Club, Indoor Bowls Club and Skegness Town Bowls Club.[320] Skegness Stadium, just outside the town, hosts stock car racing.[321]

Seacroft golf course is a traditional links course at the southern end of Skegness. It is a private members club but is open to the public upon request. Much of the course is part of a SSSI. The course has been used for various amateur championship events. It was designed by Willie Fernie and the course opened in 1900. It replaced an earlier course built in 1895.

Media

In 1922, the proprietors of the Lincolnshire Standard group of newspapers established a local version for the town, the Skegness Standard; it switched to tabloid in 1981;[214] the Standard continues as a weekly as of 2020.[322] Founded in 2001, the East Lindsey Target became the East Coast and The Wolds Target in 2017, and continues as of 2020.[323] Former newspapers include the Skegness Herald (1882–1917) and the Skegness News (1909–1964; revived in 1985 but merged into the Skegness Standard in 2007).[214][324]

Skegness is covered by BBC Yorkshire and Lincolnshire/ITV Yorkshire.[325][326] The public broadcaster BBC Radio Lincolnshire operates across the county, as does the commercial radio station Lincs FM.[327][328] Coastal Sound radio (founded in 2016) is a community radio service broadcasting from Skegness to the area and beyond by way of the internet.[329]

Historic buildings

Skegness's oldest buildings are the medieval churches of St Clement, in Skegness, and St Mary, in Winthorpe. St Clement's has a 13th-century tower; the rest of the building may be medieval, but probably dates to the mid-16th century when it is thought to have been rebuilt. There were restorations in 1884 and the 20th-century and it is grade-II* listed.[330][103] St Mary's is grade-I listed and is mostly 15th-century, with some late 12th-century elements. There are some 16th-century monumental brasses,[331] and a medieval standing cross in the churchyard, which is a scheduled monument.[332] Other buildings which predate the modern resort town include the Ivy House Farmhouse on Burgh Road, which dates to the mid or late 18th century,[333] Church Farmhouse on Church Road, which dates to the early 18th century and hosts the Church Farm Museum,[334] the 18th-century Church Farmhouse on Church End, Winthorpe,[335] and the early-19th-century Burnside Farmhouse.[336] The houses at 1–5 St Andrew's Drive are mid- to late-19th-century cottages and thought to have been built to house coastguards.[337]

Parts of the Victorian development have been recognised for their special interest. These include the Church of St Matthew[338] and the war memorial in its churchyard,[104] the Jubilee Clock Tower (built in 1898 and a landmark in the town),[339] and portions of original railings dating from the 1870s which are situated to the south and north of the clock tower;[340][341] these are all grade-II listed structures. A large portion of the later esplanade, boating lake, land north of the pier and tower gardens is also grade-II listed.[89] South Parade and Grand Parade contain 19th- and 20th-century boarding houses in the Queen Anne revival style. Modern buildings of note include the Sun Castle (1932), County Hotel (1935)[342] and The Ship Hotel (c. 1935).[343]

Notable people

Skegness has been home to several people associated with the entertainment industry. Billy Butlin (1899–1980) first set up his amusements stall on the seafront in the 1920s, opened the fairground rides south of the pier in 1929 and then established the first of his all-in holiday camps at Ingoldmells in 1936.[344] Among performers connected with the town was the comedian Arthur Lucan (1885–1954), who grew up in the Boston area and busked in Skegness after leaving home.[345] The actress Elizabeth Allan (1910–1990) was born in the town.[346][347] The rock singer and songwriter Graham Bonnet was born in Skegness in 1947.[348] The comedian Dave Allen (1936–2005) worked as a redcoat at Butlins early in his career.[349] The disgraced clergyman Harold Davidson (born 1875) performed in a circus act in the amusement park in 1937 (while campaigning for his reinstatement to the priesthood), but died that year in the town after being mauled by one of his lions.[350] The clown Jacko Fossett (1922–2004) retired to Skegness.[351]

Several notable religious figures either lived in the town or served it in some capacity: Edward Steere (1828–1882) was curate from 1858 to 1862,[352] George William Clarkson (1897–1977) was rector from 1944 to 1948,[353] Roderick Wells (born 1936) was rector from 1971 to 1978,[354] and Kenneth Thompson (1909–1975) lived in the town.[355]

Local sportspeople include Anne Pashley (died 2016), the Olympic athlete and (latterly) opera singer, who was born at Wallace's holiday camp in Skegness in 1935.[356] The footballer Ray Clemence was born in Skegness in 1948.[357] The cricketer Ray Frearson (1904–1991) played for the Skegness team and died in the town.[358][359] Among golfers, Mark Seymour died in Skegness in 1952,[360] and Helen Dobson was born there in 1971.[361]

Others with links to Skegness include the poet and art critic William Cosmo Monkhouse (born 1840), who died in the town in 1901,[362] and the novelist Vernon Scannell (died 2007), who was born there in 1922.[363] The former tabloid editor Neil Wallis started his journalistic career at the Skegness Standard in the 1960s.[364] Reginald J. G. Dutton (1886–1970), who created the shorthand Dutton Speedwords, for some time chaired Skegness Urban District Council.[365] The naval officer Sir Guy Grantham was born in the town in 1900,[366] as was the seaman Jesse Handsley, who served on Scott's first Antarctic Expedition;[367] Kingsmill Bates (1916–2006) retired to Skegness.[368] The chess champion and educator John Littlewood (1931–2009) taught at the grammar school.[369]

References

Notes

- ^ The geographer Ian Simmons says Skegness was "probably reckoned" with Ingoldmells in the Domesday Book, and that Tric was a separate vill,[26] but this view is not shared by most other authors.[25]

In Domesday there are four entries for Tric: Alan of Brittany had an estate there which was sokeland of his manor of Drayton; Eudo of Tattershall had two estates there, sokeland of his manors of Burgh Le Marsh and Addlethorpe respectively; and Robert Despenser had sokeland belonging to his manor of "Guldelsmere" which is normally identified with Ingoldmells.[27]

According to the local historian W. O. Massingberd, there was no manor of Skegness, the "greater part" (including the township, the banks, dykes, port and shore) being under the jurisdiction of the manor of Ingoldmells (though the Bishop of Lincoln had a small manor in Skegness and some land was held in the parish as a parcel of the manor of Croft).[28] The manor of Ingoldmells was Despencer's Domesday estate. It passed to his brother Urse d'Abetot probably in the late 1090s; Urse exchanged them with Robert de Lacy, lord of Pontefract.[29][30] After a period of forfeiture in the 12th century (when they were held by Hugh de Leval and probably his son Guy), the de Lacy estates in England were settled on Robert's granddaughter and heiress Albreda de Lisours, who gave them to her own grandson Roger de Lacy by agreement in 1194. The Ingoldmells property then descended with the Honour of Pontefract through the de Lacy family until Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln entailed them to his daughter Alice and her husband Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster and their descendants, with a remainder to the heirs of Thomas. After Thomas and Alice died childless, the manor was inherited in 1348 by Thomas's nephew Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster (died 1360); it passed to John of Gaunt (died 1399), the husband of the duke's daughter and eventual sole heiress Blanche, and then to their son Henry of Bolingbroke, who became Henry IV, after which the lordship of the manor merged in the crown.[31] Charles I sold it to trustees for the City of London Corporation in 1628, who disposed of it in 1657; the following year, it was acquired by Sir Drayner Massingberd, whose direct descendant possessed the manor of Ingoldmells-cum-Addlethorpe in 1902.[32] - ^ In a dissertation on Lindsey place names, Irene Bower speculates that it may have been an abbreviated form of "treow-wic", meaning "places where there are trees" and referencing submerged Neolithic forests found in this part of the coast.[34]

- ^ A "meale" was a sand dune; it comes from the Old Norse "melr", meaning "a sand bank" or "sand hill";[44] West Meles has also been recorded as Westmells.[41]

- ^ The Drake family of Shardeloes Park and the Tyrwhitts of Stainfield also had estates at Seacroft and Croft Marsh in the 17th and 18th centuries (Sir Edward Tyrwhitt had been involved in costly disputes with the first Lord Castleton over lands in Skegness). The Tyrwhitt portion was inherited by the Drakes in 1776 and included a large warren south of Skegness; the family's holdings covered 3,000 acres (1,200 hectares) and extended from Seacroft to Wainfleet.[57] A large part of this land was purchased by speculative developers in the 1920s and 1930s, but the major developer went into liquidation in 1934 and the proposed housing estates were not developed; it was purchased by the county council soon afterwards and was designated as Gibraltar Point nature reserve in 1952.[58]

- ^ The local historian Richard Gurnham describes the clientele as "local gentry", without specifying further.[60] The local historian Winston Kime also does not specify how far people travelled to holiday in the village, but quotes Canon Drummond Rawnsley as describing the visitors as "local gentry", including members of the Rawnsley, Maddison, Tennyson, Allington, Massingberd, Brackenbury and Wall families.[61] Thomas Hawkes, a resident of Spalding, recorded in the 1790s that the Fenland town was "much frequented" by visitors from Leicestershire and elsewhere on their way to bathe in the sea at Freiston, Skegness or Cleethorpes.[62]

- ^ Henry Vivian Tippet was born in Bristol on 8 November 1833 and became agent to Lord Scarbrough in 1861. He moved to Skegness in 1882 and died there on 9 February 1902.[74] The historian P. J. Waller calls him "the prime mover" behind Skegness's transformation into a modern resort.[75]

- ^ Historic England give 1885,[100] but the amusement ride historian Martin Easdown says the first switchback in Britain was installed in 1887 and that by the end of the year one was in place at Skegness.[101] It was on the sands north of the pier.

- ^ Speculative housing was put up north of Scarbrough Avenue from the 1920s by T. L. Kirk and J. H. Canning,[79] and after Castleton Boulevard was built in 1934 the original plan area was largely filled in.[111] A hundred houses were built in the Richmond Drive area under the Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1919,[106] and private developments took place around Wainfleet Road and Lincoln Road in the 1930s.[112]

- ^ Safeway was given permission to build a supermarket off Wainfleet Road in 1992; it was subsequently acquired by Morrisons.[153][154] Lidl opened a supermarket on Richmond Drive in c. 2000[155] and Tesco was granted permission to build its supermarket nearby in 2002.[156]

- ^ This was an unofficial census carried out locally.[88]

- ^ a b c d Residents aged 16 and over

- ^ a b c d Households

- ^ The previous MPs were Sir Richard Body (1997–2001)[199] and Mark Simmonds (2001–15).[200]

- ^ The earliest record of a priest at Skegness dates to 1291. The church belonged to Holy Trinity College at Tattershall in the late Middle Ages and, in 1548, the patronage was held by the Duchess of Suffolk; by 1641 the patron was Nicholas Saunderson, 1st Viscount Castleton, and the advowson passed to his eventual heirs, the Earls of Scarbrough.[267][268] Winthorpe's church was possessed by Bullington Priory in the Middle Ages. The vicarage was united with Burgh Le Marsh in 1729, but they were separated in 1914.[269]

- ^ It was in the Candleshoe Rural Deanery until 1866, when it was placed in the Candleshoe No. 2 Rural Deanery; reorganised into the Candleshoe Rural Deanery in 1910, it was placed in the Calcewaithe and Candleshoe Rural Deanery in 1968.[273]

- ^ Methodism arrived in Skegness in the early 19th century. A Wesleyan preacher visited once a month before the Wesleyans built a chapel on the High Street in 1837, which was replaced in 1848 and again in 1876; as the resort developed they were allocated a new site on Algitha Road where a chapel was built in 1881.[277] The Primitive Methodists built a chapel (Bank Chapel) on land on Roman Bank purchased in 1836; as it was closer to Winthorpe, worshippers from Skegness raised money to build their own chapel closer to the growing town in 1881; they replaced this in 1899. In 1979, the Skegness Primitive Methodists' chapel closed, with the Wesleyan chapel taking over a united congregation. The original Bank Chapel was used by people from Winthorpe until it was replaced by Seathorne Methodist Church in 1910;[277] this closed in 2009.[278]

- ^ The Baptists also held services on the beaches of Skegness from 1893, forming a branch of the church the next year; temporary accommodation was built soon afterwards which sufficed until St Paul's Baptist Church opened in 1911; it was named for the short-lived St Paul's Free Church group of worshippers which had split from the Anglican congregation in the 1890s and whose accommodation on Beresford Avenue the Baptists used before they built their own chapel.[280]