Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi | |

|---|---|

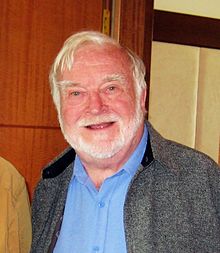

Csikszentmihalyi in 2010 | |

| Born | Mihaly Robert Csikszentmihalyi 29 September 1934 |

| Died | 20 October 2021 (aged 87) Claremont, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago |

| Occupation(s) | Psychologist, academic |

| Known for | Flow (psychology) Positive psychology Autotelic activities |

| Spouse |

Isabella Selega (m. 1961) |

| Children | 2; including Christopher |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology |

| Institutions | Claremont Graduate University University of Chicago Lake Forest College |

| Thesis | Artistic problems and their solutions; an exploration of creativity in the arts. (1965) |

| Doctoral advisor | Jacob W. Getzels |

| Doctoral students | Keith Sawyer |

Mihaly Robert Csikszentmihalyi (/ˈmiːhaɪ ˈtʃiːksɛntmiːˌhɑːjiː/, Template:Lang-hu, pronounced [ˈt͡ʃiːksɛntmihaːji ˈmihaːj] ⓘ; 29 September 1934 – 20 October 2021) was a Hungarian-American psychologist. He recognized and named the psychological concept of "flow", a highly focused mental state conducive to productivity.[1][2] He was the Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University. He was also the former head of the department of psychology at the University of Chicago and of the department of sociology and anthropology at Lake Forest College.[3]

Early life

Mihaly Robert Csikszentmihalyi was born on 29 September 1934 in Fiume,[4] now known as Rijeka,[5] then part of the Kingdom of Italy. His family name derives from the village of Csíkszentmihály in Transylvania.[6] He was the third son of a career diplomat at the Hungarian Consulate in Fiume.[5][7] His two older half-brothers died when Csikszentmihalyi was still young; one was an engineering student who was killed in the Siege of Budapest, and the other was sent to labor camps in Siberia by the Soviets.[7]

His father was appointed Hungarian Ambassador to Italy shortly after the Second World War, moving the family to Rome.[7][8] When Communists took over Hungary in 1949, Csikszentmihalyi's father resigned rather than choosing to work for the regime. The Communist regime responded by expelling his father and stripping the family of their Hungarian citizenship.[7] To earn a living, his father opened a restaurant in Rome, and Csikszentmihalyi dropped out of school to help with the family income.[5][7] At this time, the young Csikszentmihalyi, then travelling in Switzerland, saw Carl Jung give a talk on the psychology of UFO sightings.[7]

Csikszentmihalyi emigrated to the United States at the age of 22, working nights to support himself while studying at the University of Chicago.[7] He received a B.A. in 1959 and a Ph.D. in 1965, both from the University of Chicago.[7][9] He then taught at Lake Forest College, before becoming a professor at the University of Chicago in 1969.[7]

Work

Csikszentmihalyi was noted for his work in the study of happiness and creativity, but is best known as the architect of the notion of flow and for his years of research and writing on the topic.[10] Martin Seligman, former president of the American Psychological Association, described Csikszentmihalyi as the world's leading researcher on positive psychology.[11] Csikszentmihalyi once said: "Repression is not the way to virtue. When people restrain themselves out of fear, their lives are by necessity diminished. Only through freely chosen discipline can life be enjoyed and still kept within the bounds of reason."[12] His works are influential and are widely cited.[13]

Flow

In his seminal work, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Csíkszentmihályi outlined his theory that people are happiest when they are in a state of flow—a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation.[15] It is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter.[15] The flow state is colloquially known as being in the zone or in the groove.[16] It is an optimal state of intrinsic motivation, where the person is fully immersed in what they are doing.[16] This is a feeling everyone has at times, characterized by a feeling of great absorption, engagement, fulfillment, and skill—and during which temporal concerns (time, food, ego-self, etc.) are typically ignored.[16]

In an interview with Wired magazine, Csíkszentmihályi described flow as "being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost."[17]

Csikszentmihályi characterized nine component states of achieving flow, including "challenge-skill balance, merging of action and awareness, clarity of goals, immediate and unambiguous feedback, concentration on the task at hand, paradox of control, transformation of time, loss of self-consciousness, and autotelic experience".[18] To achieve a flow state, a balance must be struck between the challenge of the task and the skill of the performer.[19] If the task is too easy or too difficult, flow cannot occur as both skill level and challenge level must be matched and high; if skill and challenge are low and matched, apathy results.[19]

One state that Csikszentmihalyi researched was that of the autotelic personality.[18] The autotelic personality is one in which a person performs acts because they are intrinsically rewarding, rather than to achieve external goals.[20] Csikszentmihalyi described the autotelic personality as a trait possessed by people who can learn to enjoy situations that most others would find miserable.[21] Research has shown that aspects associated with the autotelic personality include curiosity, persistence, and humility.[22]

Motivation

Most of Csikszentmihalyi's final works focused on the idea of motivation and the factors that contribute to motivation, challenge, and overall success.[23] One personality characteristic that Csikszentmihalyi researched in detail was that of intrinsic motivation.[24] He and his colleagues found that intrinsically motivated people were more likely to be goal-directed and enjoy challenges that would lead to an increase in overall happiness.[23]

Csikszentmihalyi identified intrinsic motivation as a powerful trait to optimize and enhance positive experience, feelings, and overall well-being as a result of challenging experiences.[25] The results indicated a new personality construct, which he called work orientation, characterized by "achievement, endurance, cognitive structure, order, play, and low impulsivity".[25] A high level of work orientation in students is said to be a better predictor of grades and fulfillment of long-term goals than any school or household environmental influence.[25]

Personal life

Csikszentmihalyi married Isabella Selega in 1961.[26] He was the father of artist and professor Christopher Csíkszentmihályi, and University of California, Berkeley professor of philosophical and religious traditions of China and East Asia Mark Csikszentmihalyi.[27]

In 2009, Csikszentmihalyi was awarded the Clifton Strengths Prize.[28] He received the Széchenyi Prize at a ceremony in Budapest in 2011.[29] He was awarded the Grand Cross Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary in 2014.[8] He was a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a member of both the National Academy of Education and the Academy of Leisure Sciences.[7]

Csikszentmihalyi died on 20 October 2021 of cardiac arrest, at his home in Claremont, California, at the age of 87.[30][31]

Publications

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1975). Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-87589-261-2

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1978) "Intrinsic Rewards and Emergent Motivation" in The Hidden Costs of Reward: New Perspectives on the Psychology of Human Motivation eds Lepper, Mark R; Greene, David, Erlbaum: Hillsdale: N.Y. 205–216[32]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly and Halton, Eugene (1981). The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28774-X

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly and Larson, Reed (1984). Being Adolescent: Conflict and Growth in the Teenage Years. New York: Basic Books, Inc. ISBN 0-465-00646-9

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly and Csikszentmihalyi, Isabella Selega, eds. (1988). Optimal Experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34288-0

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-092043-2

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1994). The Evolving Self, New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092192-7

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092820-4

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1998). Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement With Everyday Life. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02411-4

- Gardner, Howard, Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Damon, William (2001). Good Work: When Excellence and Ethics Meet. New York, Basic Books.[33]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2003). Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning. Basic Books, Inc. ISBN 0-465-02608-7

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2014). The Systems Model of Creativity: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014. ISBN 978-94-017-9084-0

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2014). Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014. ISBN 978-94-017-9087-1

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2014). Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014. ISBN 978-94-017-9093-2

See also

- Attention

- Cognitive science

- Creativity

- Experience sampling method

- John Neulinger

- Motivation

- Psychology

References

- ^ O'Keefe, Paul A. (4 September 2014). "Liking Work Really Matters". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060162535.

- ^ "Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi". Claremont Graduate University. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ Risen, Clay (27 October 2021). "Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the Father of 'Flow,' Dies at 87". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Cooper, Andrew (1 September 1998). "The Man Who Found the Flow". Lion's Roar. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (8 August 2014). Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. ISBN 9789401790949.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kawamura, Kristine Marin (2014). "Kristine Marin Kawamura, PhD interviews Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, PhD". Cross Cultural Management. 21 (4). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/CCM-08-2014-0094.

- ^ a b Pontifex, Trevor (6 February 2015). "Q&A: CGU Professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi Receives Hungarian National Award". The Student Life. Claremont, California: Claremont Colleges. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi". Claremont, Calif.: Claremont Graduate University, Division of Behavorial and Organizational Sciences. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

B.A., University of Chicago, 1960

- ^ "The Pursuit of 'Flow' Is Overrated". Forge. 4 October 2021.

- ^ Thinker of the Year Award

- ^ "Virtue Quotes & Quotations". focusdep.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Nigel King & Neil Anderson (2002). Managing Innovation and Change. Cengage Learning EMEA. p. 82. (ISBN 1861527837)

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi M (1997). Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life (1st ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-465-02411-7.

- ^ a b Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row. p. 15 ISBN 0-06-092043-2

- ^ a b c Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. p. 27.

- ^ Geirland, John (1996). "Go With The Flow". Wired, September, Issue 4.09.

- ^ a b Fullagar, Clive J.; Kelloway, E. Kevin (2009). "Flow at work: an experience sampling approach". Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 82 (3): 595–615. doi:10.1348/096317908x357903.

- ^ a b "The elasticity of time in 'flow state'". Bend Bulletin. 24 September 2021.

- ^ Car, A. Positive psychology. The Science of happiness and human strengths. Hove, 2004.

- ^ "What Does It Mean To Be A Complex Person? 7 Traits To Look For". Scary Mommy. 3 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Nakamura, J. (2011). Positive psychology: Where did it come from, where is it going? In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology (pp. 2–9). New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Abuhamdeh, Sami; Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2012). "The importance of challenge for the enjoyment of intrinsically motivated, goal-directed activities". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 38 (3): 317–30. doi:10.1177/0146167211427147. PMID 22067510. S2CID 11916899.

- ^ "Why Team Flow Is a Unique Brain State". Psychology Today. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Wong, Maria; Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1991). "Motivation and academic achievement: The effects of personality traits and the quality of experience". Journal of Personality. 59 (3): 539–574. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00259.x. PMID 1960642.

- ^ "Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi". Investigating Psychology. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "Mark Csikszentmihalyi". ieas.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Nakamura, Jeanne. "2009 Clifton Strength Prize Laureate". Clifton Strengths School. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "President of Hungary honors SBOS Prof. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi with national science prize". Claremont Graduate University. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Meghalt Csíkszentmihályi Mihály, a flow elmélet atyja (in Hungarian)

- ^ Risen, Clay (27 October 2021). "Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the Father of 'Flow,' Dies at 87". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "INTRINSIC REWARDS AND EMERGENT MOTIVATIONMihaly Csikszentmihalyi". The Hidden Costs of Reward. Taylor Francis. 2015. pp. 223–234. doi:10.4324/9781315666983-19. ISBN 9781315666983. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "Good Work: When Excellence and Ethics Meet". HBSWK.edu. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

External links

- 1934 births

- 2021 deaths

- American people of Hungarian descent

- 21st-century American psychologists

- American science writers

- Claremont Graduate University faculty

- Creativity researchers

- Hungarian psychologists

- Hungarian scientists

- Members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

- Positive psychologists

- Psychology educators

- Scientists from Rijeka

- University of Chicago alumni

- University of Chicago faculty

- Yugoslav emigrants to the United States