Pumapunku

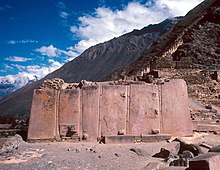

View at the ruins of Pumapunku | |

| Alternative name | Puma Punku |

|---|---|

| Altitude | 3,850 m (12,631 ft) |

| Type | an alignment of plazas and ramps centered on a man-made terraced platform mound with a sunken court and monumental complex on top |

| Part of | Tiwanaku Site |

| Length | 116.7 metres |

| Width | 167.4 metres |

| Area | at least 14 hectares |

| History | |

| Material | sifted and layered soils (mound), andesite (superstructure), sandstone (foundation and internal channels), ternary Cu–As–Ni bronze alloy (cramps), mortar of lime and sand with ground-up malachite (turquoise green plaster floor), clay (red floor) |

| Founded | 536–600 |

| Cultures | Tiwanaku empire |

| Site notes | |

| Discovered | 1549 by Pedro Cieza de León (first European visitor) |

| Excavation dates | Vranich |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Pumapunku Style architecture |

16°33′42″S 68°40′48″W / 16.56169°S 68.67993°W

Pumapunku or Puma Punku (Aymara and Quechua which literally means 'Gate of the Puma') is a 6th-century T-shaped and strategically aligned man-made terraced platform mound with a sunken court and monumental structure on top that is part of the Pumapunku complex, at the Tiwanaku Site near Tiwanacu, in western Bolivia. The Pumapunku complex is an alignment of plazas and ramps centered on the Pumapunku platform mound. Today the monumental complex on top of the platform mound lies in ruins.

It is believed to date to AD 536. After Akapana, which is believed to be "Pumapunku's twin", Pumapunku was the second most important construction in Tiwanaku. Among all the names for the areas in Tiwanaku only the names "Akapana" and "Pumapunku" have historical relevance. At Pumapunku several miniature gates which are perfect replicas of once standing full-size gateways were found. Additionally to these miniature gateways, likely, at least five gateways (and several blind miniature gateways) were once (or were intended to be) integrated into the Pumapunku monumental complex. The foundation platform of Pumapunku supported as many as eight andesite gateways. The fragments of five andesite gateways with similar characteristics to the Gateway of the Sun were found.

Tiwanaku is significant in Inca traditions because it is believed to be the site where the world was created.[1] In Aymara, Puma Punku's name means "Gate of the Puma". The Pumapunku complex consists of an unwalled western court, a central unwalled esplanade, a terraced platform mound that is faced with stone, and a walled eastern court.[2][3][4]

At its peak, Pumapunku is thought to have been "unimaginably wondrous,"[3] adorned with polished metal plaques, brightly colored ceramic and fabric ornamentation, and visited by costumed citizens, elaborately dressed priests, and elites decked in exotic jewelry. Current understanding of this complex is limited due to its age, the lack of a written record, and the current deteriorated state of the structures due to treasure hunting, looting, stone mining for building stone and railroad ballast, and natural weathering.[2][3][5]

History

When the Spanish arrived at Tiwanaku there was still standing architecture at Pumapunku. Bernabé Cobo reports that one Gateway and one "window" was still standing on one of the platforms.[6]

Description

The Pumapunku is a terraced earthen mound faced with blocks. It is 167.4 metres (549 feet) wide along its north–south axis and 116.7 metres (383 feet) long along its east–west axis. On the northeast and southeast corners of the Pumapunku, it has 20-metre (66-foot) wide projections extending 27.6 metres (91 feet) north and south from the rectangular mound.

The eastern edge of the Pumapunku is occupied by the Plataforma Lítica. This structure consists of a stone terrace 6.8 by 38.7 metres (22 by 127 feet) in dimension. This terrace is paved with multiple enormous stone blocks. It contains the largest stone slab in the Pumapunku and Tiwanaku Site, measuring 7.8 metres (26 feet) long, 5.2 metres (17 feet) wide and averages 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) thick. Based on the specific gravity of the red sandstone from which it was carved, this stone slab is estimated to weigh 131 tonnes (144 short tons).[5] The remarkable aspects of the sandstone slabs, including their size and smooth surfaces have drawn comments for several centuries.[7]

The other stonework and facing of the Pumapunku consists of a mixture of andesite and red sandstone. Pumapunku's core consists of clay, while the fill under parts of its edge consists of river sand and cobbles instead of clay. Excavations documented "three major building epochs plus repairs and re-modeling".[2][3][4][5][8]

The area within the kilometer separating the Pumapunku and Kalasasaya complexes was surveyed using ground-penetrating radar, magnetometry, induced electrical conductivity, and magnetic susceptibility. The geophysical data collected from these surveys and excavations indicate the presence of numerous man-made structures in the area between the Pumapunku and Kalasasaya complexes. These structures include the wall foundations of buildings and compounds, water conduits, pool-like features, revetments, terraces, residential compounds, and widespread gravel pavements, all of which are buried and hidden beneath the modern ground surface.[9][10]

After the area was mapped with a drone in 2016, the results showed the site has a size of seventeen hectares of which only two hectares are unearthed. There are two additional platforms still underground.[11]

Age

Noted by Andean specialist, W. H. Isbell, professor at Binghamton University,[2] a radiocarbon date was obtained by Vranich[3] from organic material from the deepest and oldest layer of mound-fill forming the Pumapunku. This layer was deposited during the first of three construction epochs, and dates the initial construction of the Pumapunku to AD 536–600 (1510 ±25 B.P. C14, calibrated date). Since the radiocarbon date came from the deepest and oldest layer of mound-fill under the andesite and sandstone stonework, the stonework was probably constructed sometime after AD 536–600. The excavation trenches of Vranich show the clay, sand, and gravel fill of the Pumapunku complex were laid directly on the sterile middle Pleistocene sediments. These excavation trenches also demonstrated the lack of any pre-Andean Middle Horizon cultural deposits within the area of the Tiwanaku Site adjacent to the Pumapunku complex.[3]

Engineering

The largest of Pumapunku's stone blocks is 7.81 metres (25.6 feet) long, 5.17 metres (17.0 feet) wide, averages 1.07 metres (3 feet 6 inches) thick, and is estimated to weigh about 131 tonnes (144 short tons). The second largest stone block found within the complex is 7.90 metres (25.9 feet) long, 2.50 metres (8 feet 2 inches) wide, and averages 1.86 metres (6 feet 1 inch) thick. Its weight is estimated to be 85.21 tonnes (93.93 short tons). Both of these stone blocks are part of the Plataforma Lítica, and are red sandstone.[5] Based on detailed petrographic and chemical analyses of samples from individual stones and known quarry sites, archaeologists concluded these and other red sandstone blocks were transported up a steep incline from a quarry near Lake Titicaca roughly 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) away. Smaller andesite blocks for stone facing and carvings came from quarries within the Copacabana Peninsula about 90 kilometres (56 miles) away from and across Lake Titicaca from the Pumapunku and the rest of the Tiwanaku Site.[3][5]

Archaeologists dispute the transport of these stones was by the large labor force of ancient Tiwanaku. Several conflicting theories attempt to imagine the ways this labor force transported the stones, although these theories remain speculative. Two common proposals involve the use of llama skin ropes, and the use of ramps and inclined planes.[12]

In assembling the walls of Pumapunku, each stone interlocked with the surrounding stones. The blocks were fit together like a puzzle, forming load-bearing joints. Jean-Pierre Protzen and Stella Nair identified a 1 to 1.5 millimeters thick thin coat of whiteish material covering some of the stones as a possible layer of mortar.[12] One common engineering technique involves cutting the top of the lower stone at a certain angle, and placing another stone on top of it which was cut at the same angle.[4] The precision with which these angles create flush joints is indicative of sophisticated knowledge of stone-cutting and a thorough understanding of descriptive geometry.[8] Many of the joints are so precise, a razor blade cannot fit between the stones.[13] Much of the masonry is characterized by accurately cut rectilinear blocks of such uniformity, they could be interchanged for one another while maintaining a level surface and even joints. Although similar, the blocks do not have the same dimensions.[12] The precise cuts suggest the possibility of pre-fabrication and mass production, technologies far in advance of the Tiwanaku’s Inca successors hundreds of years later.[12] Some of the stones are in an unfinished state, showing some of the techniques used to shape them. The architectural historians Jean-Pierre and Stella Nair who conducted the first professional field study on the stones of Tiwanaku/Pumapunku conclude:

[…] to obtain the smooth finishes, the perfectly planar faces and exact interior and exterior right angles on the finely dressed stones, they resorted to techniques unknown to the Incas and to us at this time. […] The sharp and precise 90° interior angles observed on various decorative motifs most likely were not made with hammerstones. No matter how fine the hammerstone's point, it could never produce the crisp right interior angles seen on Tiahuanaco stonework. Comparable cuts in Inca masonry all have rounded interior angles typical of the pounding technique […]. The construction tools of the Tiahuanacans, with perhaps the possible exception of hammerstones, remain essentially unknown and have yet to be discovered.[12]

According to Protzen and Nair, tools have never in history been excavated or identified that were used in the construction of Tiwanaku.[14] According to the art historian Jessica Joyce Christie, the experiments of Jean-Pierre Protzen and Stella Nair showed that the Tiwanaku artisans may have possessed additional tools which facilitated the creation of exact geometric cuts and forms and of which archeology has no record at this time.[15]

Tiwanaku engineers were also adept at developing a civic infrastructure at this complex, constructing functional irrigation systems, hydraulic mechanisms, and waterproof sewage lines.

Architecture

Pumapunku was a large earthen platform mound with three levels of stone retaining walls.[16] Its layout is not square in plan, but rather T-shaped.[17] To sustain the weight of these massive structures, Tiwanaku architects were meticulous in creating foundations, often fitting stones directly to bedrock or digging precise trenches and carefully filling them with layered sedimentary stones to support large stone blocks.[12] Modern engineers argue that base of Pumapunku was constructed using a technique called layering and depositing. By alternating layers of sand from the interior and layers of composite from the exterior, the fills overlap at the joints, grading the contact points to create a sturdy base.[4][12]

Use of cramps

Notable features at Pumapunku are I-shaped architectural cramps, composed of a unique copper-arsenic-nickel bronze alloy. These I-shaped cramps were also used on a section of canal found at the base of the terraced platform mound Akapana at Tiwanaku. These cramps hold the blocks comprising the walls and bottom of stone-lined canals to drain sunken courts. In the south canal of the Pumapunku, the I-shaped cramps were cast in place. In sharp contrast, the cramps used at the Akapana canal were fashioned by the cold hammering of copper-arsenic-nickel bronze ingots.[12][18] The unique copper-arsenic-nickel bronze alloy is also found in metal artifacts within the region between Tiwanaku and San Pedro de Atacama during the late Middle Horizon around 600–900.[19] Within Peru T-shaped sockets can also be found at the Qorikancha and Ollantaytambo.[20] The cramp technique can also be found at buildings of Ancient Egypt (e. g. at the temple of Khnum) and Ancient Greece (e. g. at the Erechtheion).[21] According to Stübel and Uhle the cramp sockets of Olympia and the Erechtheum in Athens are of the same shape that the ones of Tiwanaku. They call it "strikingly consistent choice of technical means" ("auffallend übereinstimmenden Wahl der technischen Mittel") which they think is due to "similar patterns in human way of thinking" ("Gesetzmässigkeit der menschlichen Denkentwickelung").[22]

-

cramp sockets in the foundation platforms of Pumapunku

-

cramp sockets in the foundation platforms of Pumapunku

-

Ornamental stone with I-cramp sockets which suggests that more stones were added to this block

-

T-shaped sockets at Ollantaytambo that are similar to those found at Pumapunku

-

Comparison of the Tiwanaku cramp technique (left) with that in Delphi (right)

Possible connection to Ollantaytambo

The architectural historian Jean-Pierre Protzen from University of California, Berkeley states that in the past it often has been argued that among the buildings at Ollantaytambo the monumental structures (e. g. the Wall of the six monoliths) were the work of the earlier Tiwanaku culture and have been reused by the Incas:

An argument persists that the Wall of the six monoliths and the vanished structures from which the blocks have been recycled predate the Incas and were work of the earlier Tiahuanaco culture. Support for the argument is found in the step motif carved on the fourth monolith and the T-shape sockets cut into several blocks, both believed to be hallmarks of Tiahuanaco-style architecture. […] A variant of this argument is that Tiahuanacoid elements were brought to Ollantaytambo by […] stonemasons from Lake Titicaca. […] The only question here is why stonesmasons from Lake Titicaca should have remembered anything Tiahaunacoid when for several centuries nothing like it had been built. If anything remembers me of Tiahuanaco it is […] the T-shaped sockets and the regularly coursed masonry of strongly altered andesite. […] Many T-shaped sockets are indeed found at Tiahuanaco in particular at the site of Puma Punku […].[23]

However, according to Protzen, in Ollantaytambo only T-shaped sockets are found,[24] whereas in Tiwanaku cramp sockets of a wide range of shapes — L, T, double-T or ‡, U, Y, Z — and dimensions are found.[25] Similarities between Ollantaytambo and Tiwanaku were also noticed by Heinrich Ubbelohde-Doering, Alphons Stübel and Max Uhle.[26]

Gateways of Pumapunku

Full-sized gateways

At least five gateways (and several blind miniature gateways) were once (or were intended to be) integrated into the Pumapunku monumental complex. The foundation platform of Pumapunku supported as many as eight andesite gateways. The fragments of five andesite gateways with similar characteristics to the Gateway of the Sun were found.[27]

Miniature gateways

There also exist miniature gateways at Pumapunku which are perfect replicas of once standing monumental full-sized gateways.[30] When reducing the full-sized monumental architecture to miniature architecture the Tiahuanacans applied a specific formula.[31] There also exist replicas of larger monumental structures. For example it has been shown that the much-admired carved block known as the "Escritorio del Inca" is an accurate and reduced-scale model of full-scale architecture.[32] Some of these "model stones" like "little Pumapunku" are not isolated stones but, rather, seem to fit in the context of other stones and stone fragments.[33] According to Protzen and Nair the fact that many of these "model stones" were executed in multiple exemplars bespeaks mass production.[34]

Doubly curved lintels

At Pumapunku and other areals of Tiwanaku such as Kantatayita doubly curved lintels with complicated surfaces were found. Jean-Pierre Protzen and Stella Nair point out that the "steep parabolic curve" of the doubly curved lintels (like the one of the Kantatayita lintel) would be difficult to replicate for modern stonemasons ("would tax any stonemason's skills today").[35][36]

Sculptures

There are at least two monoliths associated with the Pumapunku platform mound. One of these monoliths is the Pumapunku monolith (or Pumapunku stela). It was discovered west of the Pumapunku campus and first documented in photographs in 1876.[37][38] There is evidence that like in the case of Akapana sculptures known as Chachapumas once were guarding the entrance to Pumapunku. Chachapumas usually were placed on andesite pedestals on either side of the entrance. These sculptures show fearsome traits of predatory animals, they crouch or kneel while clutching a human head in one hand and an axe in the other. Some authors believe that the Chachapumas demanded a "sacrifice" of humans when entering the monumental structures.[39][40] Some authors believe, because of certain markings on stones found at Puma Punku, the Gate of the Sun was part of Puma Punku.[41] According to Alan Kolata the terraced platform mound depicted on the gateway of the sun is actually a stylized depiction of Pumapunku.[42] The backside of the gateway of the sun has patterns which can be found on the stone slabs and gates of Pumapunku. Therefore some assume that the gateway of the sun once formed the main entrance to Pumapunku.[43]

Roofs

The roofs of the entrance to Pumapunku were most likely out of Totora-reed stones. At the west entrance of Pumapunku Totora-reed stones were found.[44] Early visitors who saw standing architecture at Tiwanaku reported about stones which resemble "straw":

[…] [T]he roof of the hall, on the outside, looks like straw, although it is of stone. Because the Indians cover their houses with straw, and for this [room] to look like the others [houses], they dressed the stone and incised it so that it would appear like a cover of straw.[45]

Large Totora-reed stones can be found in the museum at Tiwanaku.

Cultural and spiritual significance

According to some theories, the Pumapunku complex and surrounding monumental structures like Akapana, Kalasasaya, Putuni, and Kerikala functioned as spiritual and ritual centers for the Tiwanaku. This area might be the center of the Andean world, attracting pilgrims from far away to marvel in its beauty. These structures transformed the local landscape; Pumapunku was integrated with Illimani mountain. The spiritual significance and the sense of wonder might be amplified into a "mind-altering and life-changing experience"[46] through the use of hallucinogenic plants. Examinations of hair samples exhibit remnants of psychoactive substances in many mummies found in Tiwanaku culture from Northern Chile, including babies as young as one year of age, demonstrating the importance of these substances to the Tiwanaku.[47]

Peak and decline

The Tiwanaku civilization and the use of these enclosures and platform mounds appears to peak from AD 700 to 1000, by which point, the city core and surrounding area could house 400,000 residents. An extensive infrastructure was developed, including a complex irrigation system extending more than 30 square miles (80 km2) to support cultivation of potatoes, quinoa, corn, and other various crops. During their peak centuries, the Tiwanaku culture dominated the Lake Titicaca basin as well as portions of Bolivia and Chile.[48][49]

Apparently, this culture dissolved abruptly some time around AD 1000, and researchers can only guess the reasons. A likely scenario involves rapid onset extended drought. Unable to produce the massive crop yields necessary for their large population, the Tiwanaku apparently scattered into the local mountain ranges, then disappeared shortly thereafter.[48][49] Apparently, Puma Punku was abandoned before its builders could complete it.[50][page needed]

Atlantis and aliens enthusiasts

Pumapunku is subject of pseudoscience theories on lost continents and extraterrestrial interventions. Thousands of websites and references which refer to pseudoscientific theories of alien and Atlantis enthusiasts exist.[51] The archeologist Jeb J. Card notes that Pumapunku is a fixture of books and television programs on alternative archeology and especially ancient aliens. According to Card, Atlantis and aliens enthusiasts point to the fine-cut masonry and the location of Pumapunku in the high Altiplano as mysteries.[52] The archeologist Alexei Vranich counters the ancient alien enthusiasts that well-preserved local precursors regarding the monumental complex of Pumapunku are now known (some monumental structures at Pukara and Chiripa). This fact is in his view "a solid piece of evidence" against the claims by ancient alien enthusiasts that hold Pumapunku as a best example of extraterrestrial technology, based in part on the idea that the form and design of the monumental complex of Pumapunku has no local precursors.[53] The buildings at Chiripa (which are similar to buildings of Pumapunku) were identified as "storage bins" because impressions of baskets and remains of food were found.[54] Vranich notes that generations of amateur, fringe and pseudo-archeologist claimed that the "apparent geometric perfection of Tiwanaku architecture" is a result of extraterrestrial intervention or a lost super civilization instead attributing the ruins to the inhabitants of the Titicaca basin.[55] In the 2019 issue of Public Archaeology, Franco D. Rossi of Johns Hopkins University criticizes that ancient alien theorists have called the Aymara "stone age people" who could not have built Pumapunku.[56]

Gallery

-

"nested square" symbol inside one "H-block". Identical "nested square" symbols can be found on stone stelas in the museum at Pukara."

-

One gateway at Pumapunku with similar iconography to the Gateway of the Sun

-

Fragment of one gateway at Pumapunku

-

Ornamental stones at Pumapunku

-

Ornamental stone with

I-cramp sockets which suggests that more stones were added to this block -

Detail of one of the andesite blocks

-

Nested structures which are typical for Pumapunku Style architecture

Bibliography

- Alphons Stübel, Max Uhle: Die Ruinenstätte von Tiahuanaco im Hochlande des alten Peru. Breslau (1892), p. 25–28

- Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: Who taught the Inca stonemasons their skills? A comparison of Tiahuanaco and Inca cut-stone masonry. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (1997). Volume 56, Nr. 2

- Alexei Vranich: Interpreting the meaning of ritual spaces: the temple complex of Pumapunku, Tiwanaku, Bolivia. University of Pennsylvania, 1999.

- Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (2000) Vol. 59

- Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Gateways of Tiwanaku. Symbols or passages? In: Andean Archaeology II: Art, landscape and society. Helaine Silverman and William H. Isbell (ed.) Springer, Boston, MA, 2002. pages 189–223.

- Alexei Vranich: The construction and reconstruction of ritual space at Tiwanaku, Bolivia (AD 500–1000). Journal of Field Archaeology 31.2 (2006): 121–136.

- Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013)

- Alexei Vranich, Charles Stanish: Advances in Titicaca Basin Archaeology-2. (2013), p. 140 ff.

- Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing. Heritage Science 6.1 (2018): 1–20.

References

- ^ Birx, H. James (2006). Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781412952453. ISBN 9780761930297.

- ^ a b c d Isbell, William H. (2004), "Palaces and Politics in the Andean Middle Horizon", in Evans, Susan Toby; Pillsbury, Joanne (eds.), Palaces of the Ancient New World, Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 191–246, ISBN 0-88402-300-1, archived from the original on 7 Jan 2013, retrieved 2010-04-26

- ^ a b c d e f g Vranich, A., 1999, Interpreting the Meaning of Ritual Spaces: The Temple Complex of Pumapunku, Tiwanaku, Bolivia. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b c d Vranich, A., 2006, "The Construction and Reconstruction of Ritual Space at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: A.D. 500-1000. ," Journal of Field Archaeology 31(2): 121–136.

- ^ a b c d e Ponce Sanginés, C. and G. M. Terrazas, 1970, Acerca De La Procedencia Del Material Lítico De Los Monumentos De Tiwanaku. Publication no. 21. Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013). p. 151.

- ^ Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing. p. 5.

- ^ a b Protzen, J.-P., and S.E.. Nair, 2000, "On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture:" The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 358–371.

- ^ Ernenweini, E. G., and M. L. Konns, 2007, Subsurface Imaging in Tiwanaku’s Monumental Core. Technology and Archaeology Workshop. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Williams, P. R., N. C. Couture and D. Blom, 2007 Urban Structure at Tiwanaku: Geophysical Investigations in the Andean Altiplano. In J. Wiseman and F. El-Baz, eds., pp. 423–441. Remote Sensing in Archaeology. Springer, New York.

- ^ "The secrets of Tiwanaku, revealed by a drone".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Protzen, Jean-Pierre; Stella Nair, 1997, Who Taught the Inca Stonemasons Their Skills? A Comparison of Tiahuanaco and Inca Cut-Stone Masonry: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 146–167.

- ^ Robinson, Eugene (1990). 'In Bolivia, Great Excavations; Tiwanaku Digs Unearthing New History of the New World', The Washington Post. Dec 11, 1990: d.01.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Band 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013), p. 154.

- ^ Jessica Joyce Christie: Memory landscapes of the Inka carved outcrops. Lexington Books (2015), p. 41.

- ^ Young-Sánchez, Margaret (2004). . Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca. Denver, CO: Denver Art Museum.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Band 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013), p. 59.

- ^ Lechtman, H.N., 1998, 'Architectural cramps at Tiwanaku: copper-arsenic-nickel bronze.' In Metallurgica Andina: In Honour of Hans-Gert Bachmann and Robert Maddin, edited by T. Rehren, A. Hauptmann, and J. D. Muhly, pp. 77-92. Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, Bochum, Germany.

- ^ Lechtman, H.N., 1997, El bronce arsenical y el Horizonte Medio. En Arqueología, antropología e historia en los Andes. in Homenaje a María Rostworowski, edited by R. Varón and J. Flores, pp. 153–186. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Lima.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen: Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 259. ISBN 0-19-507069-0

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013). p. 193.

- ^ Alfons Stübel, Max Uhle: Die Ruinenstätte von Tiahuanaco im Hochlande des alten Peru. Breslau (1892), p. 37.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen: Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 258 f. ISBN 0-19-507069-0

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen: Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 258 f. ISBN 0-19-507069-0

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013), p. 192.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013), p. 12.

- ^ Kevin J. Vaughn, Nicholas Tripcevich: An introduction to mining and quarrying in the ancient Andes: sociopolitical, economic and symbolic dimensions." Mining and Quarrying in the Ancient Andes. Springer, New York, NY, 2013, p. 71.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William H. Isbell: Andean Archaeology II: Art, Landscape, and Society. Springer, 2015, p. 210.

- ^ Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing. p. 6.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William H. Isbell: Andean Archaeology II: Art, Landscape, and Society. Springer, 2015, p. 210–213.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William H. Isbell: Andean Archaeology II: Art, Landscape, and Society. Springer, 2015, p. 213.

- ^ Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing. p. 6.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William H. Isbell: Andean Archaeology II: Art, Landscape, and Society. Springer, 2015, p. 212.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013), p. 151.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Gateways of Tiwanaku. Symbols or Passages? In: Andean Archaeology II: Art, Landscape and Society. Helaine Silverman and William H. Isbell (ed.) Springer, Boston, MA, 2002. p. 205 f.

- ^ John Wayne Janusek: Ancient Tiwanaku. Vol. 9. Cambridge University Press (2008), p. 135.

- ^ Anna Guengerich, John W. Janusek: The Suñawa Monolith and a Genre of Extended-Arm Sculptures at Tiwanaku, Bolivia. Ñawpa Pacha, 2020, p. 4.

- ^ Visual History – Online-Nachschlagewerk für die historische Bildforschung: Historische Fotobestände aus Südamerika im Archiv für Geographie (Leipzig), accessed on April 11, 2021; Fig. 3 shows the Pumapunku monolith; Picture note: Im Jahre 1877 umgeworfen und zerbrochen (knocked over and broken in year 1877).

- ^ Anna Guengerich, John W. Janusek: The Suñawa Monolith and a Genre of Extended-Arm Sculptures at Tiwanaku, Bolivia. Ñawpa Pacha, 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Susan Alt, Timothy R. Pauketat: New Materialisms Ancient Urbanisms. Routledge, 2019, p. 119.

- ^ Young-Sanchez, Margaret (2004). . Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca. Denver, CO: Denver Art Museum. ISBN 9780803249219.

- ^ Alan Kolata: The Tiwanaku: portrait of an Andean civilization. Cambridge: Blackwell (1993), ISBN 1-55786-183-8, p. 148.

- ^ Margaret Young-Sánchez: Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca. (2004), p. 37.

- ^ Nicholas Tripcevich, Kevin J. Vaughn: Mining and Quarrying in the Ancient Andes: Sociopolitical, Economic, and Symbolic Dimensions. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. p. 73.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Protzen, Stella Nair: The Stones of Tiahuanaco: A Study of Architecture and Construction. Vol. 75. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles (2013), p. 198; translation by Jean-Pierre Protzen and Stella Nair

- ^ Morell, Virginia (2002). Empires Across the Andes National Geographic. Vol. 201, Iss. 6: 106

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. "Drugs Found in Hair of Ancient Andean Mummies", National Geographic News, Oct. 22, 2008. Accessed Nov. 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Kolata, A.L. (1993) The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell, New York. 256 pp. ISBN 978-1-55786-183-2

- ^ a b Janusek, J.W. (2008). Ancient Tiwanaku, Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK. 362 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-01662-9

- ^ Young-Sánchez, Margaret (2004). Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca. Denver, CO: Denver Art Museum.

- ^ Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing., p. 18.

- ^ Jeb J. Card: Spooky archaeology: Myth and the science of the past. University of New Mexico Press, 2018, p. 123.

- ^ Alexei Vranich: Reconstructing ancient architecture at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the potential and promise of 3D printing., p. 15.

- ^ Margaret Young-Sánchez: Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca. (2004), p. 75.

- ^ Alexei Vranich: The Construction and Reconstruction of Ritual Space at Tiwanaku, Bolivia (AD 500–1000). Journal of Field Archaeology 31.2 (2006): 121-136, p. 133.

- ^ Rossi, Franco D. (2019-07-03). "Reckoning with the Popular Uptake of Alien Archaeology". Public Archaeology. 18 (3): 162–183. doi:10.1080/14655187.2021.1920795. ISSN 1465-5187. S2CID 237124510.

External links

- Interactive Archaeological Investigation at Pumapunku Temple – Archaeological Institute of America

- Dunning, Brian (April 20, 2010). "Skeptoid #202: The Non-Mystery of Puma Punku". Skeptoid.

- Archaeological sites in Bolivia

- Buildings and structures in La Paz Department (Bolivia)

- Indigenous topics of the Andes

- Pre-Columbian architecture

- Ruins in Bolivia

- Tourist attractions in La Paz Department (Bolivia)

- 6th-century establishments in South America

- 11th-century disestablishments in South America

- Tiwanaku culture