Tom Thomson

Tom Thomson | |

|---|---|

Thomson, c. 1910–1917 | |

| Born | Thomas John Thomson August 5, 1877 Claremont, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | July 8, 1917 (aged 39) Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Leith United Church Cemetery, Grey County, Ontario, Canada 44°37′N 80°53′W / 44.62°N 80.88°W |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Education | Self-taught[note 1] |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | |

Thomas John Thomson (August 5, 1877 – July 8, 1917) was a Canadian artist active in the early 20th century. During his short career, he produced roughly 400 oil sketches on small wood panels and approximately 50 larger works on canvas. His works consist almost entirely of landscapes, depicting trees, skies, lakes, and rivers. He used broad brush strokes and a liberal application of paint to capture the beauty and colour of the Ontario landscape. Thomson's accidental death by drowning at 39 shortly before the founding of the Group of Seven is seen as a tragedy for Canadian art.

Raised in rural Ontario, Thomson was born into a large family of farmers and displayed no immediate artistic talent. He worked several jobs before attending a business college, eventually developing skills in penmanship and copperplate writing. At the turn of the 20th century, he was employed in Seattle and Toronto as a pen artist at several different photoengraving firms, including Grip Ltd. There he met those who eventually formed the Group of Seven, including J. E. H. MacDonald, Lawren Harris, Frederick Varley, Franklin Carmichael and Arthur Lismer. In May 1912, he visited Algonquin Park—a major public park and forest reservation in Central Ontario—for the first time. It was there that he acquired his first sketching equipment and, following MacDonald's advice, began to capture nature scenes. He became enraptured with the area and repeatedly returned, typically spending his winters in Toronto and the rest of the year in the Park. His earliest paintings were not outstanding technically, but showed a good grasp of composition and colour handling. His later paintings vary in composition and contain vivid colours and thickly applied paint. His later work has had a great influence on Canadian art—paintings such as The Jack Pine and The West Wind have taken a prominent place in the culture of Canada and are some of the country's most iconic works.

Thomson developed a reputation during his lifetime as a veritable outdoorsman, talented in both fishing and canoeing, although his skills in the latter have been contested. The circumstances of his drowning on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park, linked with his image as a master canoeist, led to unsubstantiated but persistent rumours that he had been murdered or committed suicide.

Although he died before the formal establishment of the Group of Seven, Thomson is often considered an unofficial member. His art is typically exhibited with the rest of the Group's, nearly all of which remains in Canada—mainly at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg and the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound.

Life

Early years

Thomas John "Tom" Thomson was born on August 5, 1877, in Claremont, Ontario,[6] the sixth of John and Margaret Thomson's ten children.[7] He was raised in Leith, Ontario, near Owen Sound, in the municipality of Meaford.[8] Thomson and his siblings enjoyed both drawing and painting, although he did not immediately display any major talents.[7] He was eventually taken out of school for a year because of ill health, including a respiratory problem variously described as "weak lungs" or "inflammatory rheumatism".[8][9] This gave him free time to explore the woods near his home and develop an appreciation of nature.[7]

The family were unsuccessful as farmers; both Thomson and his father often abandoned their chores to go hiking, hunting and fishing.[10] Thomson regularly went on walks in Toronto with Dr. William Brodie (1831–1909), his grandmother's first cousin.[11][12] Brodie was a well-known entomologist, ornithologist and botanist, and Thomson's sister Margaret later recounted that they collected specimens on long walks together.[13][14]

Thomson was also enthusiastic about sports, once breaking his toe while playing football.[8] He was an excellent swimmer and fisherman, inheriting his passion for the latter from his grandfather and father.[15] Like most of those in his community, he regularly attended church. Some stories say that he sketched in the hymn books during services and entertained his sisters with caricatures of their neighbours. His sisters later said that they had fun "guessing who they were", indicating that he was not necessarily adept at capturing people's likeness.[8]

Each of Thomson's nine siblings received an inheritance from their paternal grandfather.[15] Thomson received $2000 in 1898 but seems to have spent it quickly.[16] A year later, he entered a machine shop apprenticeship at an iron foundry owned by William Kennedy, a close friend of his father, but left only eight months later.[15][17] Also in 1899, he volunteered to fight in the Second Boer War, but was turned down because of a medical condition.[18] He tried to enlist for the Boer War three times in all, but was denied each time.[8]

In 1901, Thomson enrolled at Canada Business College in Chatham, Ontario. The school advertised instruction in stenography, bookkeeping, business correspondence and "plain and ornamental penmanship".[15] There, he developed abilities in penmanship and copperplate—necessary skills for a clerk.[19] After graduating at the end of 1901, he travelled briefly to Winnipeg before leaving for Seattle in January 1902, joining his older brother, George Thomson.[15][19][16] George and cousin F. R. McLaren had established the Acme Business School in Seattle, listed as the 11th largest business school in the United States.[15][20] Thomson worked briefly as an elevator operator at The Diller Hotel. By 1902, two more of his brothers, Ralph and Henry, had moved west to join the family's new school.[17]

Graphic design work

Seattle (1901–04)

After studying at the business school for six months, Thomson was hired at Maring & Ladd as a pen artist, draftsman and etcher.[15][19][21] He mainly produced business cards, brochures and posters, as well as three-colour printing.[19][21] Having previously learned calligraphy, he specialized in lettering, drawing and painting.[21] While working at Maring & Ladd, he was known to be stubbornly independent; his brother Fraser wrote that, instead of completing his work according to the direction provided, he would use his own design ideas, which angered his boss.[22] Thomson may have also worked as a freelance commercial designer, but there are no extant examples of such work.[23]

He eventually moved on to a local engraving company. Despite a good salary he left by the end of 1904. He quickly returned to Leith, possibly prompted by a rejected marriage proposal after his brief summer romance with Alice Elinor Lambert.[24][21] Lambert, who never married, later became a writer;[25] in one of her stories, she describes a young girl who refuses an artist's proposal and later regrets her decision.[21]

Toronto (1905–12)

Thomson moved to Toronto in the summer of 1905.[26] His first job upon his return to Canada was at the photo-engraving firm Legg Brothers, earning $11 a week.[24][27] He spent his free time reading poetry and going to concerts, the theatre and sporting events.[28] In a letter to an aunt, he wrote, "I love poetry best."[29] Friends described him during this time as "periodically erratic and sensitive, with fits of unreasonable despondency". Apart from buying art supplies, he spent his money on expensive clothes, fine dining and tobacco.[27] Around this time, he may have studied briefly with William Cruikshank, a British artist who taught at the Ontario College of Art.[1] Cruikshank was likely Thomson's only formal art instructor.[3]

In 1908 or 1909, Thomson joined Grip Ltd., a firm in Toronto that specialized in design and lettering work.[note 4] Grip was the leading graphic-design company in the country and introduced Art Nouveau, metal engraving and the four-colour process to Canada.[35] Albert Robson, then the art director at Grip, recalled that Thomson's early work at the firm was mostly in lettering and decorative designs for booklets and labels.[36] He wrote that Thomson made friends slowly but eventually found similar interests to his coworkers.[37] Several of the employees at Grip had been members of the Toronto Art Students' League, a group of newspaper artists, illustrators and commercial artists active between 1886 and 1904.[38] The members sketched in parts of eastern Canada and published an annual calendar with illustrations depicting Canadian history and rural life.[39]

The senior artist at Grip, J. E. H. MacDonald, encouraged his staff to paint outside in their spare time to better hone their skills.[40] It was at Grip that many of the eventual members of the Group of Seven would meet. In December 1910, artist William Smithson Broadhead was hired, joined by Arthur Lismer in February 1911.[41] Robson eventually hired Frederick Varley, followed by Franklin Carmichael in April 1911.[32][42] Although Thomson was not himself a member,[43][44] it was at the Arts and Letters Club that MacDonald introduced Thomson to Lawren Harris.[42] The club was considered the "centre of living culture in Toronto", providing an informal environment for the artistic community.[45] Every member of what would become the original Group of Seven had now met.[3] MacDonald left Grip in November 1911 to do freelance work and spend more time painting,[46] after the Ontario government purchased his canvas By the River (Early Spring) (1911).[41]

-

Design for a Stained Glass Window, c. 1905–08. 34.2 x 17.1 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Decorative Landscape: Quotation from Maurice Maeterlinck, c. 1908. 32.6 x 19.5 cm. Ink on paper. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Decorative Illustration: "Blessing" by Robert Burns, 1909. 34.9 x 24.1 cm. Watercolour, graphite and ink on paper. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Painting career

Exploring Algonquin Park (1912–13)

Algonquin Park was established in 1893 by Oliver Mowat and the Ontario Legislature. Covering eighteen rectangular townships in Central Ontario, the Park was created to provide a space dedicated to recreation, wildlife and watershed protection, though logging operations continued to be permitted.[47] Thomson learned of the Park from fellow artist Tom McLean.[48][49] In May 1912, aged 34, he first visited the Park, venturing through the area on a canoe trip with his Grip colleague H. B. (Ben) Jackson.[50] Together, they took the Grand Trunk Railway from Toronto to Scotia Junction, then transferred to the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway, arriving at Canoe Lake Station.[49] McLean introduced Thomson to the Park superintendent, G. W. Barlett.[48][51] Thomson and Jackson later met ranger Harry (Bud) Callighen while they camped nearby on Smoke Lake.[48][52]

It was also at this time that Thomson acquired his first sketching equipment.[48][53] He did not yet take painting seriously. According to Jackson, Thomson did not think "his work would ever be taken seriously; in fact, he used to chuckle over the idea".[54] Instead, they spent most of their time fishing,[54] except for "a few notes, skylines and colour effects".[48]

During the same trip, Thomson read Izaak Walton's 1653 fishing guide The Compleat Angler.[55] Primarily a fisherman's bible, the book also provided a philosophy of how to live, similar to the one described in Henry David Thoreau's 1854 book Walden, or Life in the Woods, a reflection on simple living in natural surroundings.[55] His time in Algonquin Park gave him an ideal setting to imitate Walton's "contemplative" life.[56] Ben Jackson wrote:

Tom was never understood by lots of people, was very quiet, modest and, as a friend of mine spoke of him, a gentle soul. He cared nothing for social life, but with one or two companions on a sketching and fishing trip with his pipe and Hudson Bay tobacco going, he was a delightful companion. If a party or the boys got a little loud or rough Tom would get his sketching kit and wander off alone. At times he liked to be that way, wanted to be by himself commune [sic] with nature.[56]

Upon returning to Toronto, Jackson published an article about his and Thomson's experience in the Park in the Toronto Sunday World, included in which were several illustrations.[48] After this initial experience, Thomson and another colleague, William Broadhead, went on a two-month expedition, going up the Spanish River and into Mississagi Forest Reserve (today Mississagi Provincial Park).[56] Thomson's transition from commercial art towards his own original style of painting became apparent around this time.[57][58] Much of his artwork from this trip, mainly oil sketches and photographs, was lost during two canoe spills;[57] the first was on Green Lake in a rain squall and the second in a series of rapids.[59][note 5]

In fall 1912, Albert Robson, Grip's art director, moved to the design firm Rous & Mann.[3] A month after returning to Toronto, Thomson followed Robson and left Grip to join Rous & Mann too.[47][40][61] They were soon joined by Varley, Carmichael and Lismer.[59] Robson later spoke favourably of Thomson's loyalty, calling him "a most diligent, reliable and capable craftsman".[36] Robson's success in attracting great talent was well understood.[62] Employee Leonard Rossell believed that the key to Robson's success "was that the artists felt that he was interested in them personally and did all he could to further their progress. Those who worked there were all allowed time off to pursue their studies ... Tom Thomson, so far as I know, never took definite lessons from anyone, yet he progressed quicker than any of us. But what he did was probably of more advantage to him. He took several months off in the summer and spent them in Algonquin Park."[63]

In October, MacDonald introduced Thomson to James MacCallum.[59] A frequent visitor to the Ontario Society of Artists' (OSA) exhibitions, MacCallum was admitted to the Arts and Letters Club in January 1912. There, he met artists such as John William Beatty, Arthur Heming, MacDonald and Harris.[59] MacCallum eventually persuaded Thomson to leave Rous and Mann and start a painting career.[47] In October 1913, MacCallum introduced Thomson to A. Y. Jackson, later a founder of the Group of Seven.[64] MacCallum recognized Thomson's and Jackson's talents and offered to cover their expenses for one year if they committed themselves to painting full time.[65][66] MacCallum and Jackson both encouraged Thomson to "take up painting seriously, [but] he showed no enthusiasm. The chances of earning a livelihood by it did not appear to him promising. He was sensitive and independent, and feared he might become an object of patronage."[64] MacCallum wrote that when he first saw Thomson's sketches, he recognized their "truthfulness, their feeling and their sympathy with the grim fascinating northland ... they made me feel that the North had gripped Thomson as it had gripped me since I was eleven when I first sailed and paddled through its silent places." He described Thomson's paintings as "dark, muddy in colour, tight and not wanting in technical defects".[67] After Thomson's death, MacCallum helped preserve and advocated for his work.[66]

Thomson accepted MacCallum's offer under the same terms offered to Jackson.[64] He travelled around Ontario with his colleagues, especially to the wilderness of Ontario, which was to become a major source of inspiration. Regarding Algonquin Park, he wrote in a letter to MacCallum: "The best I can do does not do the place much justice in the way of beauty."[68] He ventured to rural areas near Toronto and tried to capture the surrounding nature. He may have worked as a fire ranger on the Mattagami reserve.[69] Addison and Little suggest that he guided fishing tours,[70][71] although Hill finds this unlikely since Thomson had only spent a few weeks in the Park the previous year.[72] Thomson became as familiar with logging scenes as with nature in the Park and painted them both.[73]

While returning to Toronto in November 1912, Thomson stopped in Huntsville.[72][74] The visit was possibly to meet with Winifred Trainor, a woman whose family owned a cottage on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. Trainor was later rumoured to have been engaged to Thomson with a wedding planned for the late 1917, although little is known about their relationship.[75][76][note 6]

Thomson first exhibited with the OSA in March 1913, selling his painting Northern Lake (1912–13) to the Ontario Government for $250 (equivalent to CAD$6,500 in 2023).[77][78] The sale afforded him time to paint and sketch through the summer and fall of 1913.[79]

"Sketch" indicates that the work is a smaller oil work, generally on wood panel. The dimensions are often close to 21.6 × 26.7 cm (8½ x 10½ in.) but sometimes as small as 12.8 x 18.2 cm (51⁄16 x 73⁄16 in.).

-

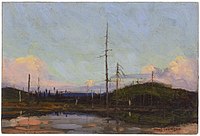

Old Lumber Dam, Algonquin Park, Spring 1912. Sketch. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

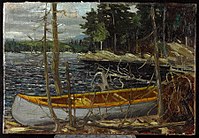

The Canoe, Spring or fall 1912. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Mississagi, 1912. Sketch. Private collection

-

Evening, Fall 1913. Sketch. Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Early recognition (1914–15)

Thomson often experienced self-doubt. A. Y. Jackson recalled that in the fall of 1914, Thomson threw his sketch box into the woods out of frustration,[80] and was "so shy he could hardly be induced to show his sketches".[43] Harris expressed similar sentiments, writing that Thomson "had no opinion of his own work", and would even throw burnt matches at his paintings.[81] Several of the canvases he sent to exhibitions remained unsigned.[note 7] If someone praised one of his sketches, he immediately gave it to them as a gift.[43] A turning point in his career came in 1914, when the National Gallery of Canada, under the directorship of Eric Brown, began to acquire his paintings. Although the money was not enough to live on, the recognition was unheard of for an unknown artist.[83]

For several years he shared a studio and living quarters with fellow artists, initially living in the Studio Building with Jackson in January 1914. Jackson described the Studio Building as "a lively centre for new ideas, experiments, discussions, plans for the future and visions of an art inspired by the Canadian countryside".[84] It was there that Thomson, "after much self-deprecation, finally submitted to becoming a full-time artist".[85] They split the rent—$22 a month—on the ground floor while construction on the rest of the building was finished.[28] After Jackson moved out in December to go to Montreal, Carmichael took his place.[28][86][87] Thomson and Carmichael shared a studio space through the winter.[88] On March 3, 1914, Thomson was nominated as a member of the OSA by Lismer and T. G. Greene. He was elected on the 17th. He did not participate in any of their activities beyond sending paintings for annual exhibitions.[43] Harris described Thomson's strange working hours years later:

When he was in Toronto, Tom rarely left the shack in the daytime and then only when it was absolutely necessary. He took his exercise at night. He would put on his snowshoes and tramp the length of the Rosedale ravine and out into the country, and return before dawn.[89]

In late April 1914, Thomson arrived in Algonquin Park, where he was joined by Lismer on May 9. They camped on Molly's Island in Smoke Lake, travelling to Canoe, Smoke, Ragged, Crown and Wolf Lakes.[90] He spent his spring and summer divided between Georgian Bay and Algonquin Park, visiting James MacCallum by canoe. His travels during this time have proved difficult to discern, with such a large amount of ground covered in such a short time, painting the French River, Byng Inlet, Parry Sound and Go-Home Bay from May 24 through August 10.[91] H. A. Callighen, a park ranger, wrote in his journal that Thomson and Lismer left Algonquin Park on May 24.[92] By May 30, Thomson was at Parry Sound and on June 1 was camped at the French River with MacCallum.[92][93]

Art historian Joan Murray noted that Thomson was at Go-Home Bay for the next two months, or at least until August 10 when he was seen again in Algonquin Park by Callighan.[94] According to Wadland, if this timeline is correct, it would require "an extraordinary canoeist ... The difficulty is augmented by the fact of stopping to sketch at intervals along the way."[93] Wadland suggested that Thomson may have travelled by train at some point and by steamship thereafter.[91] Addison and Harwood instead said that Thomson had found much of the inland "monotonously flat" and the rapids "ordinary".[95] Wadland found this characterization unhelpful, pointing out that the rapids Thomson had faced were hardly "ordinary".[93]

MacCallum provided specific dates for two of Thomson's paintings—May 30 and June 1 for Parry Sound Harbour and Spring, French River, respectively.[92][96] These are some of the only instances of precise dating for his work.[97] Cottage on a Rocky Shore is a depiction of MacCallum's cottage contrasted with the vast expanse of sky and water. Evening, Pine Island is of a nearby island MacCallum took Thomson to visit.[98] He continued to paint around the islands until he departed, probably because he found MacCallum's cottage too demanding socially, writing to Varley that it was "too much like north Rosedale".[98][99]

Thomson continued canoeing alone until he met with A. Y. Jackson at Canoe Lake in mid-September. Though World War I had erupted that year, he and Jackson went on a canoe trip, in October meeting up with Varley and his wife Maud, as well as Lismer and his wife Esther, and daughter Marjorie.[98] This marked the first time three Group of Seven members painted together, and the only time they worked with Thomson.[58][83] In his 1958 autobiography, A Painter's Country, A. Y. Jackson wrote that, "Had it not been for the war, the Group [of Seven] would have formed several years earlier and it would have included Thomson."[100]

Why Thomson did not serve in the war has been debated.[101] Mark Robinson and Thomson's family said that he was turned down after multiple attempts to enlist, likely due to his poor health and age but also possibly because he had flat feet.[8][18][83] Blodwen Davies wrote that Thomson's artist friends tried to convince him to not risk his life, but he decided to secretly volunteer anyway.[102] Andrew Hunter has found this scenario to be improbable, especially given that other artist friends did volunteer for the war, such as A. Y. Jackson.[101] Thomson's sister suggested that he was a pacifist and that "he hated war and said simply in 1914 that he never would kill anyone but would like to help in a hospital, if accepted".[103] William Colgate wrote that Thomson "brooded much upon" the war and that "he himself did not enlist. Rumour has it that he tried, and failed to pass the doctor. This is doubtful."[104] Edward Godin, a companion, said "We had many discussions on the war. As I remember it he did not think that Canada should be involved. He was very outspoken in his opposition to Government patronage. Especially in the Militia. I do not think that he would offer himself for service. I know up until that time he had not tried to enlist."[101] There is only one verifiable example of Thomson's opinion on the war, taken from a letter he wrote to J. E. H. MacDonald in 1915:

As with yourself, I can't get used to the idea of [A. Y.] Jackson being in the machine and it is rotten that in this so-called civilized age that such things can exist, but since this war has started it will have to go on until one side wins out, and of course there is no doubt which side it will be, and we will see Jackson back on the job once more.[105][106]

With MacCallum's year of financial support over, Thomson's financial future became uncertain.[87] He briefly looked into applying for a position as a park ranger, but balked after seeing that it could take months for the application to go through. Instead, he considered working in an engraving shop over the winter.[98] He made little effort to sell his paintings, preferring to give them away, though he brought in some money from the paintings he sold.[107] In mid-November, he donated In Algonquin Park to an exhibition organized to raise money for the Canadian Patriotic Fund. It was sold to Marion Long for $50 (equivalent to CAD$1,300 in 2023).[87]

In the spring of 1915, Thomson returned to Algonquin Park earlier than he had in any previous year and had already painted twenty-eight sketches by April 22. From April through July, he spent much of his time fishing, assisting groups on several different lakes, and sketching when he had time.[108] In July, he was invited to send paintings to the Nova Scotia Provincial Exhibition in September. Because he was in Algonquin Park, his friends selected three works to send—two unidentified works from 1914 and the sketch Canadian Wildflowers.[109] From the end of September to mid-October, he spent his time at Mowat, a village on the north end of Canoe Lake.[110] By November, he was at Round Lake with Tom Wattie and Robert McComb.[111][112] In late November, he returned to Toronto and moved into a shack behind the Studio Building that Harris and MacCallum fixed up for him,[113][114] renting it for $1 a month.[115][note 8]

In 1915, MacCallum commissioned MacDonald, Lismer and Thomson to paint decorative panels for his cottage on Go-Home Bay. In October of that year, MacDonald went up to take dimensions.[119][120] Thomson produced four panels which were probably meant to go over the windows. In April 1916, when MacDonald and Lismer went to install them, they found that MacDonald's measurements were incorrect and the panels did not fit.[121][122][note 9]

-

Canoe Lake, Spring 1914. Sketch. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

-

Smoke Lake, Summer 1915. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

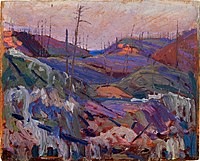

Fire-Swept Hills, Summer or fall 1915. Sketch. Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Autumn Foliage, Fall or winter 1915. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

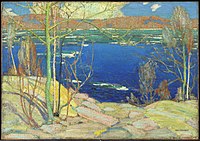

Spring Ice, Winter 1915–16. 72.0 × 102.3 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Artistic peak (1916–17)

In March 1916, Thomson exhibited four canvases with the OSA: In the Northland (at that time titled The Birches), Spring Ice, Moonlight and October (then titled The Hardwoods), all of which were painted over the winter of 1915–16. Sir Edmund Walker and Eric Brown of the National Gallery of Canada wanted to purchase In the Northland, but Montreal trustee Francis Shepherd convinced them to purchase Spring Ice instead.[119] The reception of Thomson's paintings at this time was mixed. Margaret Fairbairn of the Toronto Daily Star wrote, "Mr. Tom Thomson's 'The Birches' and 'The Hardwoods' show a fondness for intense yellows and orange and strong blue, altogether a fearless use of violent colour which can scarcely be called pleasing, and yet which seems an exaggeration of a truthful feeling that time will temper."[125] A more favourable take came from artist Wyly Grier in The Christian Science Monitor:

Tom Thomson again reveals his capacity to be modern and remain individual. His early pictures—in which the quality of naivete had all the genuineness of the effort of the tyro and was not the counterfeit of it which is so much in evidence in the intensely rejuvenated works of the highly sophisticated—showed the faculty for affectionate and truthful record by a receptive eye and faithful hand; but his work today has reached higher levels of technical accomplishment. His Moonlight, Spring Ice and The Birches are among his best.[127]

In The Canadian Courier, painter Estelle Kerr also spoke positively, describing Thomson as "one of the most promising of Canadian painters who follows the impressionist movement and his work reveals himself to be a fine colourist, a clever technician, and a truthful interpreter of the north land in its various aspects".[128]

In 1916, Thomson left for Algonquin Park earlier than any previous year, evidenced by the many snow studies he produced at this time.[129] In April or early May, MacCallum, Harris and his cousin Chester Harris joined Thomson at Cauchon Lake for a canoe trip.[129][130] After MacCallum and Chester left, Harris and Thomson paddled together to Aura Lee Lake.[131] Thomson produced many sketches which varied in composition, although they all had vivid colour and thickly-applied paint.[130] MacCallum was present when he painted his Sketch for "The Jack Pine", writing that the tree fell over onto Thomson before the sketch was completed. He added that Harris thought the tree killed Thomson, "but he sprang up and continued painting".[129]

At the end of May, Thomson took a job as a fire ranger stationed at Achray on Grand Lake with Ed Godin. He followed the Booth Lumber Company's log drive down the Petawawa River to the north end of the park.[132] He found that fire ranging and painting did not mix well together,[133] writing, "[I] have done very little sketching this summer as the two jobs don't fit in ... When we are travelling two go together, one for canoe and the other the pack. And there's no place for a sketch outfit when your [sic] fire ranging. We are not fired yet but I am hoping to get put off right away."[134] He likely returned to Toronto in late October or early November.[133]

Over the following winter, encouragement from Harris, MacDonald and MacCallum saw Thomson move into the most productive portion of his career,[135] with Thomson writing in a letter that he "got quite a lot done".[136] Despite this, he did not submit any paintings to the OSA exhibition in the spring of 1917.[126] It was during this time that he produced many of his most famous works, including The Jack Pine and The West Wind.[137] MacCallum suggested that several canvas works were unfinished, including Woodland Waterfall, The Pointers and The Drive.[138] Barker Fairley similarly described The West Wind as unfinished.[139] Charles Hill has written that there are no reasons to believe Woodland Waterfall was unfinished.[126] Similarly, while it has sometimes been suggested that The Drive was modified after Thomson's death,[140] a reproduction from 1918 displays no discernible differences.[141]

Thomson returned to Canoe Lake at the beginning of April, arriving early enough to paint the remaining snow and the ice breaking up on the surrounding lakes. He had little money but wrote that he could manage for about a year. On April 28, 1917, he received a guide's licence. Unlike previous years, he remained at Mowat with Lieutenant Crombine and his wife, Daphne. Thomson invited Daphne Crombie to select something from his spring sketches as a gift, and she selected Path Behind Mowat Lodge.[142]

Besides the deep love he had come to develop for Algonquin Park, Thomson was beginning to show an eagerness to depict areas beyond the park and explore other northern subjects.[143] In an April 1917 letter to his brother-in-law, he wrote that he was considering taking the Canadian Northern Railway west so he could paint the Canadian Rockies in July and August.[144][145] A. Y. Jackson suggested Thomson would have travelled even further north, just as the other members of the Group of Seven eventually did.[144]

-

Petawawa Gorges, Fall 1916. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Wild Geese: Sketch for "Chill November", Fall 1916. Sketch. Museum London, London

-

Woodland Waterfall, Winter 1916–17. 121.9 x 132.5 cm. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

The Pointers, Winter 1916–17. 101 x 114.6 cm. Hart House, University of Toronto

-

Open Water, Joe Creek, Spring 1917. Sketch. Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Death

On July 8, 1917, Thomson disappeared during a canoeing trip on Canoe Lake.[146] His upturned canoe was spotted later in the afternoon, and his body was discovered in the lake eight days later.[146][147] It was noted that he had a four-inch cut on his right temple and had bled from his right ear. The cause of death was officially determined to be "accidental drowning".[146][148][149] The day after the body was discovered, it was interred in Mowat Cemetery near Canoe Lake.[146][150][note 11] Under the direction of Thomson's older brother George, the body was exhumed two days later, and re-interred on July 21 in the family plot beside the Leith Presbyterian Church in what is now the Municipality of Meaford, Ontario.[151][152][153]

In September 1917, J. E. H. MacDonald and John William Beatty erected a memorial cairn at Hayhurst Point on Canoe Lake, to honour Thomson where he died.[151][154][155]

There has been much speculation about the circumstances of Thomson's death, including that he was murdered or committed suicide. Though these ideas lack substance, they have continued to persist in the popular culture.[146][156] Andrew Hunter has pointed to Park ranger Mark Robinson as being largely responsible for the suggestion that there was more to his death than accidental drowning. Hunter expands on this thought, writing, "I am convinced that people's desire to believe the Thomson murder mystery/soap opera is rooted in the firmly fixed idea that he was an expert woodsman, intimate with nature. Such figures aren't supposed to die by 'accident.' If they do, it is like Grey Owl's being exposed as an Englishman."[157]

Art and technique

Artistic development

Thomson was largely self-taught. His experiences as a graphic designer with Toronto's Grip Ltd. honed his draughtsmanship.[3] Although he began painting and drawing at an early age, it was only in 1912, when he was well into his thirties, that he began to paint seriously.[57][58] His first trips to Algonquin Park inspired him to follow the lead of fellow artists in producing oil sketches of natural scenes on small, rectangular panels for easy portability while travelling. Between 1912 and his death in 1917, Thomson produced hundreds of these small sketches, many of which are now considered works in their own right, and are mostly found in the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg and the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound.[158]

Thomson produced nearly all of his works between 1912 and 1917. Most of his large canvases were completed in his most productive period, from late 1916 to early 1917.[158] The patronage of James MacCallum enabled Thomson's transition from graphic designer to professional painter.[65][66] Although the Group of Seven was not founded until after his death, his work was sympathetic to that of group members A. Y. Jackson, Frederick Varley, and Arthur Lismer. These artists shared an appreciation for rugged, unkempt natural scenery, and all used broad brush strokes and a liberal application of paint to capture the beauty and colour of the Ontario landscape.[159][160] Thomson's art also bears some stylistic resemblance to the work of European post-impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh.[161] Other key influences were the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, styles with which he became familiar while working in the graphic arts.[162]

Thomson's artwork is typically divided into two bodies: the first are the small oil sketches on wood panels, of which there are around 400, and the second is of around 50 larger works on canvas.[158] The smaller sketches were typically done en plein air in "the North", primarily Algonquin Park, in the spring, summer and fall.[163] Mark Robinson later recounted that Thomson usually had a particular motif he wanted to depict before going into nature to find a comparison.[164][165] The larger canvases were instead completed over the winter in Thomson's studio—an old utility shack with a wood-burning stove on the grounds of the Studio Building, an artist's enclave in Rosedale, Toronto.[28][166][167] About a dozen of the major canvases were derived directly from smaller sketches.[note 12] Paintings like Northern River, Spring Ice, The Jack Pine and The West Wind were only later expanded into larger oil paintings.[158]

Sketches from 1913 and earlier use a variety of supports, including canvas laid down on paperboard, canvas laid down on wood and commercial canvas-board. In 1914, he began to favour the larger birch wood panels used by A. Y. Jackson, typically measuring around 21.6 × 26.7 cm (8½ × 10½ in.). From late 1914 on, Thomson alternated between painting on these inexpensive pieces of wood—some from crates, bookbinder's board, and other assorted sources—and composite wood-pulp boards.[169]

Although the sketches were produced quickly, the canvases were developed over weeks or even months. Compared to the panels, they display an "inherent formality",[170] and lack much of the "energy, spontaneity, and immediacy" of the original sketches.[168] The transition from small to large required a reinvention or elaboration of the original details; by comparing sketches with their respective canvases, one can see the changes Thomson made in colour, detail and background textural patterns.[170][171] Although few of the larger paintings were sold during his lifetime, they formed the basis of posthumous exhibitions, including one at Wembley in London in 1924, that eventually brought his work to international attention.[172][173][174]

Described as having an "idiosyncratic palette", Thomson had exceptional control of colour.[175] He often mixed available pigments to create new, unusual colours that, along with his brushwork, made his art instantly recognizable regardless of its subject.[176] His painting style and the atmosphere, colours and forms of his work influenced the work of his colleagues and friends, especially Jackson, Lismer, MacDonald, Harris and Carmichael.[177]

Series and themes

Trees

Thomson's most famous paintings are his depictions of pine trees, particularly The Jack Pine and The West Wind. David Silcox has described these paintings as "the visual equivalent of a national anthem, for they have come to represent the spirit of the whole country, notwithstanding the fact that vast tracts of Canada have no pine trees",[178] and as "so majestic and memorable that nearly everyone knows them".[179] Arthur Lismer described them similarly, saying that the tree in The West Wind was a symbol of the Canadian character, unyielding to the wind and emblematic of steadfastness and resolution.[180]

Thomson had a great enthusiasm for trees and worked to capture their forms, their surrounding locations, and the effect of the seasons on them. He normally depicted trees as amalgamated masses, giving "form structure and colour by dragging paint in bold strokes over an underlying tone".[181] His favourite motif was of a slight hill next to a body of water.[182] His enthusiasm is especially apparent in an anecdote from Ernest Freure, who invited Thomson to camp on an island on Georgian Bay:

One day while we were together on my island, I was talking to Tom about my plans for cleaning up the dead wood and trees and I said I was going to cut down all the trees but he said, "No, don't do that, they are beautiful."[183]

The theme of the single tree is common in Art Nouveau,[184] while the motif of the lone, heroic tree goes back even further to at least Caspar David Friedrich and early German Romanticism.[185] Thomson may also have been influenced by the work of MacDonald while working at Grip Limited. MacDonald in turn was influenced by the landscape art of John Constable, whose work he likely saw while in England from 1903 to 1906.[184] Constable's art influenced Thomson's as well, something apparent when Constable's Stoke-by-Nayland (c. 1810–11) is compared with Thomson's Poplars by a Lake.[186]

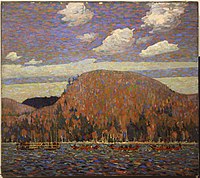

Thomson's earlier paintings were closer to literal renderings of the trees in front of him, and as he progressed the trees became more expressive as Thomson amplified their individual qualities.[187] Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay shows the broken, high-keyed colour that Thomson and his colleagues experimented with later in his career, and is similar to Lismer's Sunglow. While Lismer only applied the technique to the water, Thomson applied it throughout the composition.[188] According to MacCallum, Thomson worked on Pine Island, Georgian Bay over an extended period.[188] He wrote that this painting had "more emotion and feeling than any other of [Thomson's] canvases".[188] In contrast, MacDonald found it "rather commonplace in color & composition & not representative of Thomson at his best".[189]

-

Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay, Winter 1914-1915. 71.5 × 76.3 cm. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Pine Trees at Sunset, Summer 1915. Sketch. Private collection, Toronto

-

Pine Island, Georgian Bay, Winter 1914–16. 153.2 x 127.7 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

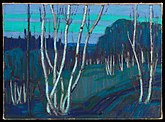

The Birch Grove, Autumn, Winter 1915–16. 101.6 × 116.8 cm. Art Gallery of Hamilton, Hamilton

-

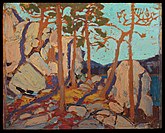

Pine Cleft Rocks, Spring 1916. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

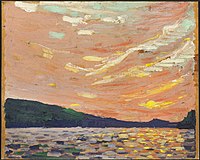

Skies

Thomson was preoccupied with capturing the sky, especially near the end of his career from 1915 onward. Paintings like Sunset—which was painted at water level in a canoe—illustrate his excited brushstrokes in capturing the lake's reflection.[190] The painting was done over a grey-green ground, adding depth to both the light of the sky and the reflecting water.[117] Paintings from 1913 and on consistently utilize the perspective of the canoe, with a narrow foreground of water, a distant shoreline and a dominating sky.[191][192]

The 1915 volcanic eruption of Lassen Peak in California provided dramatic sunrises and sunsets in the northern hemisphere for the year. These skies provided artistic inspiration for Thomson and other artists in the same way that the eruption of Krakatoa in the previous century had inspired Edvard Munch.[192][193] Sky effects were one of Thomson's main interests for the entire year, indicated by his heightened use of colour.[117]

Harold Town has compared Sky (The Light That Never Was) to the works of J. M. W. Turner. In particular, he notes the way that the sky "[creeps] into the landscape, big rhythms supplanting small movement". The horizon disappears and pure movement is left behind.[194]

-

Sky (The Light that Never Was), Summer 1913. Sketch. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

Sketch for Morning Cloud, Fall 1913. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Wild Cherries, Spring, Spring 1915. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Summer Day, Summer 1915. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Round Lake, Mud Bay, Fall 1915. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

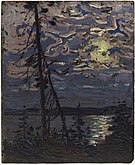

Nocturnes

Thomson produced more nocturnes than the rest of the Group of Seven combined—roughly two dozen.[195][196] MacCallum recalled that Thomson often spent his nights lying in his canoe in the middle of the lake, stargazing and avoiding mosquitoes.[195][197] Besides capturing the nighttime sky, he also captured silhouettes of spruce and birch trees, lumber camps, two moose emerging from water and the northern lights, painting five different sketches of the aurora.[196][198]

Mark Robinson recounted that Thomson stood and contemplated the aurora for an extended period of time before going back into his cabin to paint by lamplight.[199] He sometimes completed nocturnes this way, going back and forth between painting indoors and looking at the subject outside until he completed the sketch.[200] Other times, given the difficulty of painting by moonlight, many of the nocturnes were painted entirely from memory. MacCallum confirmed that the sketch Moose at Night was completed in this way, writing on the back "Winter 1916—at studio",[142] implying it was probably painted in Toronto.[201] His moonlight paintings use a "dreamy, pale-toned style", applying the techniques of Impressionism in his observations of light, reflection and atmosphere.[200]

-

Moonlight, Winter 1913–14. 52.9 × 77.1 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

Moonlight, Fall 1915. Sketch. Private collection, Toronto

-

Silver Birches, Winter 1915–16. 40.9 × 56.0 cm. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Moose at Night, Winter 1916. Sketch. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

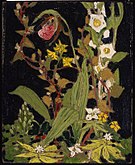

Flowers

As was typical for painters of the early twentieth century, Thomson produced still lifes of flowers,[202] all of which appear in the form of sketches. His love of flowers may have developed from his father who, as a neighbour noted, had "a permanent half acre of a really good garden which was always worth going to see".[203] Thomson's time spent as a child collecting samples with his naturalist relative William Brodie may have similarly influenced him, though his interest in painting flowers seems to have been more focused on patterning and decoration than on the horticultural specifics of the subject.[204]

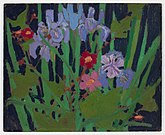

These paintings, especially Marguerites, Wood Lilies and Vetch and Wildflowers, are particularly powerful examples of the genre.[202] J. E. H. MacDonald—himself deeply invested in floral imagery—was so captured by Marguerites, Wood Lilies and Vetch that he kept it for himself, writing "Not For Sale" on the back.[205][206] Thomson's work is contrasted from MacDonald's by what Joan Murray calls, "its elegant, slightly funky form and throwaway spontaneity."[207] Lawren Harris instead noted Wildflowers as a favourite, writing "1st class" on the verso. The colour of the sketch is less brilliant, but has superb brushwork and is well coordinated, setting blues against yellows and reds against whites.[208]

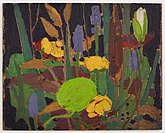

Responding to his subject with improvization,[209] every painting is different in its colour scheme and arrangement.[210] In all the sketches, he redirected emphasis from the delicacy of the flowers towards simple broad strokes of colour, something Harold Town thought "[imparted] a toughness of design sometimes missing in his harder themes of rock and bracken".[211] In Water Flowers particularly, the shapes are handled so summarily that the focus moves entirely to the colour of the flowers.[212] This, combined with the black background, produces a more abstract effect.[213][214] The black backdrop also causes the colours of the flowers to appear more vivid.[206][215]

-

Canadian Wildflower, Summer 1915. Sketch. National Gallery on Canada, Ottawa

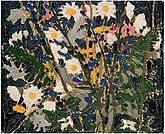

-

Marguerites, Wood Lilies and Vetch, Summer 1915. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Water Flowers, Summer 1915. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Wild Flowers, Summer 1915. Sketch. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

-

Moccasin Flower (Orchids, Algonquin Park), Spring 1916. Sketch. Private collection

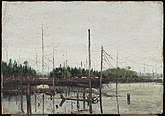

Industry in nature

During Thomson's time in Algonquin Park, logging and the lumber industry were a constant presence.[216][note 13] He often painted the machinery left behind by lumber companies; Lismer, MacDonald and he were especially drawn to the subject. A. Y. Jackson wrote,

It was a ragged country; a lumber company had slashed it up, and fire had run through it ... Thomson was much indebted to the lumber companies. They had built dams and log chutes, and had made clearings for camps. But for them, the landscape would have been just bush, difficult to travel in and with nothing to paint.[217]

Around 1916, Thomson followed the drive of logs down the Madawaska River, painting the subject in The Drive. MacDonald similarly expressed the drive in his 1915 painting Logs on the Gatineau.[218] Besides the dams, pointer and alligator boats and log drives that appear in Thomson's work, other less obvious depictions of the lumber industry are evident. For example, areas cleared out due to logging appear in early sketches, such as Canoe Lake (1913) and Red Forest. The painting Drowned Land similarly displays the damage caused by logging operations and flooding due to damming.[47] As well, the white birches present in many paintings only thrive in "sunny, open areas whose previous tree cover had been removed",[219] meaning that logging was in some way necessary for them to flourish.[216]

Thomson's and the Group of Seven's work reflects the typical Canadian attitudes of the time, namely that the available natural resources were meant to be exploited.[73][220][note 14] Harold Town has argued that, while Thomson was not directly critical of industry, mining and logging, he "did not glorify industry in the bush."[223] Paul Walton of McMaster University noted that Thomson occasionally referenced both the lumbering and tourism practices of Algonquin Park and "did not entirely ignore the damaging effects of logging on the environment ... but for the most part he concentrated on newly opened vista of sky and water or on finding decorative patterns of colour, form, and texture in the tangle of underbrush, smaller trees, and bared rock, the 'bush' that was often the remnant of the original forest."[224] Jackson first noted these distinctions in Thomson's works, from those "showing a low shore line and a big sky" and those "finding happy color motives amid [the] tangle and confusion" of "his waste of rock and swamp."[225]

-

Drowned Land, Fall 1912. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Logging, Spring, Algonquin Park, Spring 1916. Sketch. Private collection

-

Bateaux, Summer 1916. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

The Drive, Winter 1916–17. 120 × 137.5 cm. University of Guelph Collection, Art Gallery of Guelph, Guelph

People

Thomson, like most of the members of the Group of Seven, rarely painted people.[226][227][note 15] When he did, the human subject was usually someone close to him personally, such as the depiction of Shannon Fraser In the Sugar Bush. Harold Town observed that both Thomson and Canadian artist David Milne "shared in common a similar inability to draw the human figure",[229] something professor John Wadland thought was "embarrassingly evident" in several of Thomson's portraits.[229] Thomson's most successful attempts at capturing people typically feature figures far off in the distance, allowing them to blend in to the scene. This is apparent in paintings like Little Cauchon Lake, Bateaux, The Drive, The Pointers and Tea Lake Dam.[226]

Town described paintings like Man with Axe (Lowery Dixon) Splitting Wood as stiff, yet still held together in a cohesive crudity. He described Figure of a Lady, Laura differently, interpreting it as a tender work, "well-designed and plainly expressed, this loving picture is so secure in intention that it survives, indeed triumphs, over the severe cracking of the paint".[228] The figure in The Poacher is recorded deliberately, including his hat, hunting vest and blue shirt. The hot coal grill in front of him is drying his poach—likely venison.[230]

-

Man with Axe (Lowery Dickson) Splitting Wood, Fall 1915. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Figure of a Lady, Laura, Fall 1915. Sketch. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

-

Little Cauchon Lake, Spring 1916. Sketch. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

In the Sugar Bush (Shannon Fraser), Spring 1916. Sketch. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

The Fisherman, Winter 1916–17. 51.3 x 56.5 cm. Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton

Legacy and influence

Since his death, Thomson's work has grown in value and popularity. Group of Seven member Arthur Lismer wrote that he "is the manifestation of the Canadian character".[231] Another contemporaneous Canadian painter, David Milne, wrote to National Gallery of Canada Director H. O. McCurry in 1930, "Your Canadian art apparently, for now at least, went down in Canoe Lake. Tom Thomson still stands as the Canadian painter, harsh, brilliant, brittle, uncouth, not only most Canadian but most creative. How the few things of his stick in one's mind."[232] Murray notes that Thomson's influence can be seen in the work of later Canadian artists, including Rae Johnson, Joyce Wieland, Gordon Rayner and Michael Snow.[233] Sherrill Grace wrote that for Roy Kiyooka and Dennis Lee, he "is a haunting presence" and "embodies the Canadian artistic identity".[234]

As of 2015, the highest price achieved by a Thomson sketch was Early Spring, Canoe Lake, which sold in 2009 for CAD$2,749,500. Few major canvases remain in private collections, making the record unlikely to be broken.[235] One example of the demand his work has achieved is the previously lost Sketch for Lake in Algonquin Park; discovered in an Edmonton basement in 2018, it sold for nearly half a million dollars at a Toronto auction.[236][237] The increased value of his work has led to the discovery of numerous forgeries on the market,[238] such as those produced by convicted forger William Firth MacGregor.[239][note 16] Art historian Joan Murray assembled a catalogue raisonné of Thomson works until her retirement in 2016.[241]

In 1967, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery opened in Owen Sound.[242] In 1968, Thomson's shack from behind the Studio Building was moved to the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg.[243] Many of his works are also on display at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario.[158] In 2004, another historical marker honouring Thomson was moved from its previous location near the centre of Leith to the graveyard in which he is now buried. The gravesite has become a popular spot for visitors to the area with many fans of his work leaving pennies or art supplies behind as tribute.[244]

Though best known for his painting, Thomson is often mythologized as a veritable outdoorsman. James MacCallum contributed stories to this image. He has often been remembered as an expert canoeist, though David Silcox has argued that this image is romanticized.[245] In the case of fishing, he was no doubt proficient. He had a deep love of fishing for his entire life, so much so that his reputation through Algonquin Park was equally divided between art and angling. Most who visited the Park were led by hired guides, but he travelled through the park on his own. Many of his fishing locations appear in his work.[246]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Thomson may have briefly studied under British artist William Cruikshank around 1905.[1] It is also possible that he read John Ruskin's 1857 handbook The Elements of Drawing while learning to draw.[2] Besides these instances it is clear that he had no other art instruction.[3] Refer to Death and legacy of Tom Thomson § An "untainted" artist.

- ^ Though he died before the Group of Seven's founding in 1920, Thomson's connection to the artists and the art they created is unquestionable.[4] In his 1964 book The Story of the Group of Seven, Lawren Harris wrote,

I have, in my story of the Group, included Tom Thomson as a working member, although the name of the group did not originate until after his death. Tom Thomson was, nevertheless, as vital to the movement, as much a part of its formation and development, as any other member.[5]

- ^ "Sketch" indicates that the work is a smaller oil work, generally on wood panel. The dimensions are often close to 21.6 × 26.7 cm (8½ × 10½ in.) but sometimes as small as 12.8 × 18.2 cm (51⁄16 x 73⁄16 in.).

- ^ Sources disagree on the timing of Thomson's hiring. Grip supervisor Albert H. Robson wrote in 1932 that he was hired in 1907,[30] but by 1937 Robson was instead writing that he was hired in 1908.[31] Robert Stacey has suggested December 1908;[19] David Silcox the beginning of 1909;[3] Art historians Joan Murray and Gregory Humeniuk each suggest December 1908 or January 1909.[32][33] Curator Charles Hill noted that Thomson is listed in the Toronto City Directory between 1906 and 1909 as working with Legg Bros. Photo Engravers; in 1910 merely as an artist living at 99 Gerrard E.; and in 1911 as at Grip Ltd. Hill supposes that Thomson therefore likely began at Grip in late 1909, after the information for the 1910 directory was collected.[34]

- ^ Thomson wrote in a letter to his friend M. J. (John) McRuer:

We started in at Bisco and took a long trip on the lakes around there going up the Spanish River and over into the Mississauga [Mississagi] water we got a great many good snapshots of game—mostly moose and some sketches, but we had a dump in the forty-mile rapids which is near the end of our trip and lost most of our stuff—we only saved 2 rolls of film out of about 14 dozen. Outside of that we had a peach of a time as the Mississauga is considered the finest canoe trip in the world.[60]

- ^ For more regarding Thomson's possible romantic relationship with Trainor, refer to MacGregor (2010).

- ^ Unsigned paintings exhibited during Thomson's lifetime include: Northern Lake (1912–13); Morning Cloud; Moonlight (1913–14); Split Rock, Georgian Bay; Canadian Wildflowers; Moonlight (1915); and October.[82]

- ^ In his 1959 piece, "My Memories of Tom Thomson", Thoreau MacDonald cited November 1915 as when Thomson moved into the shack behind the Studio Building.[116] Most sources agree with this, including Charles Hill,[117] William Little[114] and Addison & Harwood.[113] David Silcox has written that the move happened in either late 1914[28] or early 1915.[28][118]

- ^ MacDonald's measurements were 44½ × 37", but the panels installed were 27 × 37". The panels Thomson produced were 47½ × 38".[123][124]

- ^ In the Northland was originally titled The Birches.[119] All of Thomson's canvases from the winter of 1916–17 were titled after his death.[126]

- ^ Mowat Cemetery was located at 45°33′47″N 78°43′42″W / 45.56306°N 78.72833°W.

- ^ Silcox & Town report that "barely a dozen" of the canvases were developed directly from the sketches,[158] while Joan Murray puts the number at eight.[168]

- ^ For more regarding the industrialization of Algonquin Park, refer to Edwards (1976), Lloyd (2000), and McKenna (1976).

- ^ An article in the Owen Sound Sun describing Thomson's 1912 visit to the Mississagi Forest Reserve wrote that "technology gave value to the landscape"[221] and placed emphasis on the mineral, forest, water-power, and fish and game resources rather than on any scenic beauty the land possessed.[222]

- ^ Notable exceptions are Frederick Varley and Frank Johnston, Varley's main interest being people, faces and figures.[227][228] At the beginning of his career, Lawren Harris captured people in nearly all of his depictions of Toronto and did several portraits, but later moved on to only depicting landscapes. Edwin Holgate painted the female figure and completed several nudes.[227]

- ^ Murray identifies two Thomson forgeries in her 1994 book, Tom Thomson: The Last Spring, each of which feature "ill-defined [landscapes], half-hidden by the smeary paint handling and heavy impasto."[240] In 2021–22, the Art Gallery of Hamilton and Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario held an exhibition comparing known Thomson forgeries to authentic works, alongside paintings with uncertain origins.[241]

Citations

- ^ a b

- Murray (1986), p. 6

- Hill (2002), pp. 113, 113n18

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 43

- ^ Murray (1999), p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Silcox (2015), p. 9.

- ^ Waddington & Waddington (2016), p. 29.

- ^ Harris (1964), p. 7.

- ^ Klages (2016), p. 10.

- ^ a b c Silcox (2015), p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Silcox & Town (2017), p. 41.

- ^ MacDonald (1917), p. 47, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 113.

- ^ Murray (1998), pp. 14–15, 22–25.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 57.

- ^ Murray (1999), p. 5.

- ^ Murray (1999), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Wadland (2002), p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hill (2002), p. 113.

- ^ a b Silcox & Town (2017), p. 42.

- ^ a b Silcox (2015), p. 6.

- ^ a b Silcox (2006), pp. 107–08.

- ^ a b c d e Stacey (2002), p. 50.

- ^ Murray (1971), p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Silcox (2015), p. 7.

- ^ Stacey (2002), pp. 50–51.

- ^ Stacey (2002), p. 51.

- ^ a b Stacey (2002), p. 52.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 43.

- ^ Wadland (2002), p. 92.

- ^ a b Silcox (2015), p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Silcox (2006), p. 127.

- ^ Murray (1999), p. viii.

- ^ Robson (1932), p. 138, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 113n16.

- ^ Robson (1937), p. 5, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 113n16.

- ^ a b Murray (2002b), p. 310.

- ^ Humeniuk (2020), p. 315.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 113n16.

- ^ King (2010), p. 14.

- ^ a b Robson (1932), p. 138, quoted in Stacey (2002), p. 53.

- ^ Robson (1937), p. 6, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 114.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 115.

- ^ Stacey (1998), p. 96n9.

- ^ a b Stacey (2002), p. 58.

- ^ a b Hill (2002), p. 114.

- ^ a b Murray (2004), p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Hill (2002), p. 117.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 9n2.

- ^ Reid (1970), p. 28.

- ^ Stacey & Bishop (1996), p. 118.

- ^ a b c d Wadland (2002), p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e f Hill (2002), p. 118.

- ^ a b Wadland (2002), p. 94.

- ^

- Hunter (2002), p. 25

- Klages (2016), p. 21

- Silcox (2006), p. 20

- Silcox (2015), p. 10

- Stacey (2002), p. 57

- ^ Addison & Harwood (1969), p. 88n4.

- ^ Addison (1974), p. 75.

- ^ Murray (2011), p. 3.

- ^ a b Hunter (2002), pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Hunter (2002), p. 26.

- ^ a b c Hunter (2002), p. 27.

- ^ a b c Silcox (2015), p. 10.

- ^ a b c Silcox (2006), p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Hill (2002), p. 119.

- ^ Murray (2002a), p. 297.

- ^ Klages (2016), p. 23.

- ^ Stacey (2002), pp. 57–58.

- ^ Rossell (c. 1951), p. 3, quoted in Stacey (2002), p. 58.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 122.

- ^ a b Silcox (2006), p. 21.

- ^ a b c Silcox (2015), p. 11.

- ^ MacCallum (1918), p. 376.

- ^ Murray (2002a), p. 298.

- ^ Murray (2002b), p. 312.

- ^ Addison (1974), p. 18.

- ^ Little (1970), p. 13.

- ^ a b Hill (2002), p. 121.

- ^ a b Silcox (2015), p. 58.

- ^ Addison (1974), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 12.

- ^ King (2010), pp. 169–70.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 120.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 12.

- ^ Stacey (2002), p. 60.

- ^ Jackson (1958), p. 31.

- ^ Hill (2002), pp. 117, 117n36.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 117n35.

- ^ a b c Silcox (2015), p. 13.

- ^ Jackson (1958), p. 27.

- ^ Jackson (1933), p. 138, quoted in Roza (1997), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Murray (2006), p. 17.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 128.

- ^ King (2010), pp. 154–59.

- ^ Harris (1964), quoted in Silcox (2006), p. 127.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 124.

- ^ a b Wadland (2002), p. 105.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 125.

- ^ a b c Wadland (2002), p. 105n70.

- ^ Murray (2002b), p. 313.

- ^ Addison & Harwood (1969), p. 32.

- ^ Murray (2004), p. 108.

- ^ Hill (2002), pp. 125–26.

- ^ a b c d Hill (2002), p. 126.

- ^ Waddington & Waddington (2016), p. 131.

- ^ Jackson (1958), pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c Hunter (2002), p. 40.

- ^ Davies (1930), pp. 29–31, quoted in Hunter (2002), p. 40.

- ^ Thomson (1956), pp. 21–24, quoted in Hunter (2002), p. 40.

- ^ Colgate (1946), p. 15, quoted in Hunter (2002), p. 40.

- ^ Murray (2002a), p. 300–01.

- ^ Hunter (2002), p. 41.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 14.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 131.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 133.

- ^ Wadland (2002), p. 102.

- ^ Ghent (1949), quoted in Hill (2002), p. 131.

- ^ Addison & Harwood (1969), p. 46.

- ^ a b Addison & Harwood (1969), p. 84.

- ^ a b Little (1970), p. 179.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 13.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 132n119.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 132.

- ^ Silcox (2015), pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 136.

- ^ Landry (1990), p. 26.

- ^ Reid (1970), p. 93.

- ^ Stacey & Bishop (1996), p. 119.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 136n134.

- ^ Reid (1969), pp. 49, 69.

- ^ Fairbairn (1916), quoted in Hill (2002), p. 136.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 139.

- ^ Hill (2002), pp. 136–37.

- ^ Kerr (1916), p. 13, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 137.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 137.

- ^ a b Silcox (2015), p. 16.

- ^ Reid (1970), p. 126.

- ^ Hill (2002), pp. 137–38.

- ^ a b Hill (2002), p. 138.

- ^ Murray (2002a), pp. 302–03.

- ^ Silcox (2006), p. 20.

- ^ Murray (2002a), pp. 303–04.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 17.

- ^ MacCallum (1918), pp. 375–85, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 139.

- ^ Fairley (1920), p. 246, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 139.

- ^ Forsey (1975), p. 188, quoted in Hill (2002), p. 139.

- ^ Hill (2002), pp. 140, 140n167.

- ^ a b Hill (2002), p. 141.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 18.

- ^ a b Murray (1999), p. 122.

- ^ Murray (2002a), pp. 304–05.

- ^ a b c d e Silcox & Town (2017), p. 49.

- ^ Robinson (1917), quoted in Hill (2002), p. 142, 333n182

- ^ Howland (1917).

- ^ Ranney (1931).

- ^ Fraser (1917), quoted in Hill (2002), p. 142, 333n184

- ^ a b Hill (2002), p. 142.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 49–50.

- ^ "Historic Leith Church". www.meaford.ca. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Silcox (2006), p. 213.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 240.

- ^ Klages (2016).

- ^ Hunter (2002), p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f Silcox & Town (2017), p. 181.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 40.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 140.

- ^ Silcox (2015), pp. 30, 48.

- ^

- Hill (2002), p. 113

- Murray (1999), p. 7

- Silcox (2015), pp. 22, 47, 68, 71

- Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 94, 210

- ^ Silcox (2015), pp. 59–60.

- ^ Davies (1935), pp. 108–09, quoted in Hill (2002), pp. 133–34.

- ^ Little (1970), pp. 187–89.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 181–85.

- ^ Brown (1998), pp. 151, 158.

- ^ a b Murray (2011), p. 6.

- ^ Webster-Cook & Ruggles (2002), pp. 146–47.

- ^ a b Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 181–82.

- ^ Murray (2006), p. 92.

- ^ Jessup (2007), p. 188.

- ^ Dawn (2007), p. 193.

- ^ Dejardin (2011).

- ^ Silcox (2015), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 73.

- ^ Silcox (2006), p. 212: "[Thomson's sketches] directly inspired and informed the work of his colleagues, particularly Jackson, Lismer, MacDonald and Lawren Harris ..."

Murray (1990), p. 155: "... Thomson's way of painting strongly influenced Carmichael." - ^ Silcox (2006), p. 50.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 19.

- ^ Lismer (1934), pp. 163–64, quoted in Murray (1999), p. 114.

- ^ MacCallum (1918), pp. 379–80.

- ^ Murray (1999), p. 8.

- ^ Murray (1999), p. v.

- ^ a b Murray (1999), p. 7.

- ^ Halkes (2003), p. 99.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 69.

- ^ Murray (1999), p. 15.

- ^ a b c Hill (2002), p. 129.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 129n106.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 27.

- ^ Silcox (2006), p. 211.

- ^ a b Silcox (2015), p. 28.

- ^ King (2010), pp. 182–83.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 58.

- ^ a b Silcox (2015), p. 38.

- ^ a b Silcox & Town (2017), p. 221.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 221, 236.

- ^ Silcox (2015), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Little (1970), p. 198.

- ^ a b Murray (2011), p. 70.

- ^ Hill (2002), p. 134n127.

- ^ a b Silcox (2006), p. 75.

- ^ Murray (1986), p. 41.

- ^ King (2010), p. 182.

- ^ Murray (2002c), pp. 12, 102.

- ^ a b Murray (2011), p. 50.

- ^ Murray (2002c), p. 12.

- ^ Murray (2011), p. 52.

- ^ Murray (2002c), p. 100.

- ^ Murray (2002c), p. 98.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 96.

- ^ Murray (1986), p. 58.

- ^ Murray (2002c), pp. 14, 106.

- ^ Murray (2011), p. 54.

- ^ Murray (2002c), pp. 13, 98.

- ^ a b Hunter (2002), p. 30.

- ^ Jackson (1958), quoted in Sloan (2010), pp. 70–71 & Silcox (2006), p. 211.

- ^ Silcox (2006), pp. 211, 255–56.

- ^ Strickland (1996), p. 19, quoted in Hunter (2002), p. 30.

- ^ Silcox (2006), pp. 210–11.

- ^ Nelles (1974), p. 51, quoted in Walton (2007), p. 142, 142n9

- ^ Murray (1971), p. 23, quoted in Walton (2007), p. 142, 142n10

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 72.

- ^ Walton (2007), p. 143.

- ^ Jackson (1919), p. 2, quoted in Walton (2007), p. 143n19

- ^ a b Hunter (2002), p. 32.

- ^ a b c Silcox (2006), p. 76.

- ^ a b Silcox & Town (2017), p. 124.

- ^ a b Wadland (2002), p. 99.

- ^ Murray (2011), p. 96.

- ^ Lismer (1934), pp. 163–64, quoted in Hunter (2002), p. 35.

- ^ Dejardin (2018), pp. 17, 194.

- ^ Murray (1998), pp. 98–101, quoted in Grace (2004a), p. 81

- ^ Grace (2004a), p. 96.

- ^ Silcox (2015), p. 66.

- ^ Vikander (2018).

- ^ The Canadian Press (2018).

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), p. 182; Silcox (2015), p. 74.

- ^ Dellandrea (2017).

- ^ Murray (1994a), pp. 3, 4.

- ^ a b Lederman (2021).

- ^ "Tom Thomson Art Gallery". City of Owen Sound. June 2018.

- ^ Dexter (1968).

- ^ "Leith United Church | Heritage Meaford". www.heritagemeaford.com. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 236–37.

- ^ Hunter (2002), pp. 28–29.

Sources

Books

- Addison, Ottelyn; Harwood, Elizabeth (1969). Tom Thomson: The Algonquin Years. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- Addison, Ottelyn (1974). Early Days in Algonquin Park. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 978-0-07077-786-6.

- Brown, W. Douglas (1998). "The Arts and Crafts Architecture of Eden Smith". In Latham, David (ed.). Scarlet Hunters: Pre-Raphaelitism in Canada. Toronto: Archives of Canadian Art. ISBN 978-1-89423-400-9.

- Colgate, William, ed. (1946). Two Letters of Tom Thomson, 1915 and 1916. Weston: Old Rectory Press.

- Davies, Blodwen (1930). Paddle & Palette: The Story of Tom Thomson. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- ——————— (1935). A Study of Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness. Toronto: Discuss Press.

- Dawn, Leslie (2007). "The Britishness of Canadian Art". In O'Brian, John; White, Peter (eds.). Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-77353-244-1.

- Dejardin, Ian A. C. (2011). Painting Canada: Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery. ISBN 978-0-85667-686-4.

- ———————— (2018). "Dazzle and Kick: The Life of David Milne". In Milroy, Sarah; Dejardin, Ian A. C. (eds.). David Milne: Modern Painting. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-1-78130-061-9.

- Edwards, Ron (1976). Petawawa River Survey Sites: A History. Algonquin Region: Ministry of Natural Resources.

- Forsey, William C. (1975). The Ontario Community Collects: A Survey of Canadian Painting from 1766 to the Present. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario. ISBN 9780919876125.

- Grace, Sherrill (2004a). Inventing Tom Thomson: From Biographical Fictions to Fictional Autobiographies and Reproductions. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-77352-752-2.

- Harris, Lawren S. (1964). The Story of the Group of Seven. Toronto: Rous and Mann Press.

- Hill, Charles (2002). "Tom Thomson, Painter". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 111–43. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Humeniuk, Gregory (2020). "Chronology". In Dejardin, Ian A. C.; Milroy, Sarah (eds.). A Like Vision: The Group of Seven & Tom Thomson. Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions. pp. 314–21. ISBN 978-1-77310-205-4.

- Hunter, Andrew (2002). "Mapping Tom". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 19–46. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Jackson, A. Y. (1958). A Painter's Country. Toronto: Clarke Irwin.

- Jessup, Lynda (2007). "Art for a Nation". In O'Brian, John; White, Peter (eds.). Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-77353-244-1.

- King, Ross (2010). Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-807-8.

- Klages, Gregory (2016). The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-45973-196-7.

- Landry, Pierre (1990). The MacCallum-Jackman Cottage Mural Paintings. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada. ISBN 978-0-888-84598-6.

- Little, William T. (1970). The Tom Thomson Mystery. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd.

- Lloyd, Donald L. (2000). Canoeing Algonquin Park. Toronto: Donald L. Lloyd. ISBN 978-0-96865-560-3.

- MacGregor, Roy (2010). Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0-30735-739-7.

- McKenna, Ed (1976). A Systematic Approach to the History of the Forest Industry in Algonquin Park, 1835–1913, with an Evaluation of Algonquin Park's Historical Resources and an Assessment of Algonquin Park's Historical Zone System. Algonquin Region: Ministry of Natural Resources.

- Murray, Joan (1971). The Art of Tom Thomson. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario.

- —————— (1986). The Best of Tom Thomson. Edmonton: Hurtig. ISBN 978-0-88830-299-1.

- —————— (1994a). Tom Thomson: The Last Spring. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55002-218-6.

- —————— (1998). Tom Thomson: Design for A Canadian Hero. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55002-315-2.

- —————— (1999). Tom Thomson: Trees. Toronto: McArthur & Co. ISBN 978-1-55278-092-3.

- —————— (2002a). "Tom Thomson's Letters". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 297–306. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- —————— (2002b). "Chronology". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 307–17. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- —————— (2002c). Flowers: J. E. H. MacDonald, Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. Toronto: McArthur & Co. ISBN 978-1-55278-326-9.

- —————— (2004). Water: Lawren Harris and the Group of Seven. Toronto: McArthur & Co. pp. 108–15. ISBN 978-1-55278-457-0.

- —————— (2006). Rocks: Franklin Carmichael, Arthur Lismer, and the Group of Seven. Toronto: McArthur & Co. pp. 92–97. ISBN 978-1-55278-616-1.

- —————— (2011). A Treasury of Tom Thomson. Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-886-3.

- Nelles, H. V. (1974). The Politics of Development: Forests, Mines and Hydro-Electric Power in Ontario, 1849-1941. Toronto.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Reid, Dennis (1969). The MacCallum Bequest. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada.

- —————— (1970). The Group of Seven. Ottawa: The National Gallery of Canada.

- Robson, Albert H. (1932). Canadian Landscape Painters. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- ———————— (1937). Tom Thomson: Painter of Our North Country, 1877–1917. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- Roza, Alexandra M. (1997). Towards a Modern Canadian Art 1910–1936: The Group of Seven, A. J. M. Smith and F. R. Scott (PDF) (Thesis). McGill University.

- Silcox, David P. (2006). The Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. Richmond Hill: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-154-8.

- ——————— (2015). Tom Thomson: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-48710-075-9.

- ———————; Town, Harold (2017). Tom Thomson: The Silence and the Storm (Revised, Expanded ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 978-1-44344-234-3.

- Sloan, Johanne (2010). Joyce Wieland's the Far Shore. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-44261-060-6.

- Stacey, Robert; Bishop, Hunter (1996). J. E. H. MacDonald, Designer: An Anthology of Graphic Design, Illustration and Lettering. Ottawa: Archives of Canadian Art, Carleton University Press. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Stacey, Robert (1998). "Making Us See the Light: Franklin Brownell's 'Middle Passage'". North by South: The Art of Peleg Franklin Brownell (1857–1946). Ottawa: Ottawa Art Gallery. ISBN 978-1-89510-847-7.

- ——————— (2002). "Tom Thomson as Applied Artist". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 47–63. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Strickland, Dan (1996). Trees of Algonquin Provincial Park. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. ISBN 978-1-89570-920-9.

- Waddington, Jim; Waddington, Sue (2016). In the Footsteps of the Group of Seven (paperback ed.). Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 978-0-86492-891-7.

- Wadland, John (2002). "Tom Thomson's Places". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 85–109. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Walton, Paul H. (2007). "The Group of Seven and Northern Development". In O'Brian, John; White, Peter (eds.). Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-77353-244-1.

- Webster-Cook, Sandra; Ruggles, Anne (2002). "Technical Studies on Thomson's Materials and Working Methods". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 145–51. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

Articles

- Canadian Press, The (May 30, 2018). "Tom Thomson sketch discovered in Edmonton basement sells for $481K at auction". Toronto Star. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- Dellandrea, Jon S. (July–August 2017). "Brush with Infamy". Literary Review of Canada. Vol. 26, no. 6. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- Dexter, Gail (June 1, 1968). "Tom Thomson's dollar-a-month shack becomes a Group of Seven shrine". Toronto Star.

- Fairbairn, Margaret (March 11, 1916). "Some Pictures at the Art Gallery". Toronto Daily Star.

- Fairley, Barker (March 1920). "Tom Thomson and Others". The Rebel. 3 (6): 244–48.