Theoretical key

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2018) |

In music theory, a theoretical key is a key whose key signature would have at least one double-flat (![]() ) or double-sharp (

) or double-sharp (![]() ).

).

Some musical keys are not normally used because they would require a double sharp or double flat in the key signature. For example, G♯ major requires eight sharps, and, since there are only seven scale tones, one tone requires a double sharp. The enharmonically equivalent key of A♭ only requires four flats, making it clearer to read.

Enharmonic equivalence

|

|

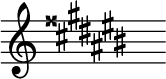

| G♯ major, a key signature with a double-sharp | A♭ major, equivalent key |

| G♯ major: | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F |

| A♭ major: | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G |

The key of G♯ major is a theoretical key because its key signature has an F![]() , giving it eight sharps. An equal-tempered scale in G♯ major contains the same pitches as the A♭ major scale, making the two keys enharmonically equivalent. In the absence of other factors, this key would generally be notated as A♭ major.

, giving it eight sharps. An equal-tempered scale in G♯ major contains the same pitches as the A♭ major scale, making the two keys enharmonically equivalent. In the absence of other factors, this key would generally be notated as A♭ major.

Modulation

While a piece of Western music generally has a home key, a passage within it may modulate to another key, which is usually closely related to the home key (in the Baroque and early Classical eras), that is, close to the original in the circle of fifths. When the key has zero or few sharps or flats, the notation of both keys is straightforward. But if the home key has many sharps or flats, particularly if the new key is on the opposite side, double sharps or flats may be necessary, or an enharmonically equivalent key may be used to avoid double sharps or flats.

In the bottom three places on the circle of fifths the enharmonic equivalents can be notated with single sharps or flats and so are not theoretical keys:

| Major (minor) | Key signature | Major (minor) | Key signature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (g♯) | 5 sharps | C♭ (a♭) | 7 flats | |

| F♯ (d♯) | 6 sharps | G♭ (e♭) | 6 flats | |

| C♯ (a♯) | 7 sharps | D♭ (b♭) | 5 flats |

The need to consider theoretical keys

When a parallel key ascends the opposite side of the circle from its home key, theory suggests that double-sharps and double-flats would have to be incorporated into the notated key signature. The following theoretical keys would require up to seven double-sharps or double-flats. Six of these are the parallel major/minor keys of those above.

| Major | Key signature | Minor |

|---|---|---|

| F♭ major (E major) | 8 flats (4 sharps) | D♭ minor (C♯ minor) |

| B |

9 flats (3 sharps) | G♭ minor (F♯ minor) |

| E |

10 flats (2 sharps) | C♭ minor (B minor) |

| A |

11 flats (1 sharp) | F♭ minor (E minor) |

| D |

12 flats (no flats or sharps) | B |

| G |

13 flats (1 flat) | E |

| C |

14 flat (2 flats) | A |

| G♯ major (A♭ major) | 8 sharps (4 flats) | E♯ minor (F minor) |

| D♯ major (E♭ major) | 9 sharp (3 flats) | B♯ minor (C minor) |

| A♯ major (B♭ major) | 10 sharps (2 flats) | F |

| E♯ major (F major) | 11 sharps (1 flat) | C |

| B♯ major (C major) | 12 sharps (no flats or sharps) | G |

| F |

13 sharps (1 sharp) | D |

| C |

14 sharps (2 sharps) | A |

A piece in a major key might modulate up a fifth to the dominant (a common occurrence in Western music), resulting in a new key signature with an additional sharp. If the original key was C-sharp, such a modulation would lead to the theoretical key of G-sharp major (with eight sharps) requiring an F![]() in place of the F♯. This section could be written using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A-flat major instead. Claude Debussy's Suite bergamasque does this: in the third movement "Clair de lune" the key shifts from D-flat major to D-flat minor (eight flats) for a few measures but the passage is notated in C-sharp minor (four sharps); the same happens in the final movement, "Passepied", in which a G-sharp major section is written as A-flat major.

in place of the F♯. This section could be written using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A-flat major instead. Claude Debussy's Suite bergamasque does this: in the third movement "Clair de lune" the key shifts from D-flat major to D-flat minor (eight flats) for a few measures but the passage is notated in C-sharp minor (four sharps); the same happens in the final movement, "Passepied", in which a G-sharp major section is written as A-flat major.

Such passages may instead be notated with the use of double-sharp or double-flat accidentals, as in this example from Johann Sebastian Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, which has this passage in G-sharp major in measures 10-12.

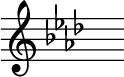

In very few cases, theoretical keys are used directly, with the necessary double-accidentals in the key signature. The final pages of John Foulds' A World Requiem are written in G♯ major (with F![]() in the key signature), No. 18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele is written in B♯ major, and the third movement of Victor Ewald's Brass Quintet Op. 8 is written in F♭ major (with B

in the key signature), No. 18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele is written in B♯ major, and the third movement of Victor Ewald's Brass Quintet Op. 8 is written in F♭ major (with B![]() in the key signature).[1][2] Examples of theoretical key signatures are pictured below:

in the key signature).[1][2] Examples of theoretical key signatures are pictured below:

There does not appear to be a standard on how to notate theoretical key signatures:

- The default behaviour of LilyPond (pictured above) writes all single signs in the circle-of-fifths order, before proceeding to the double signs. This is the format used in John Foulds' A World Requiem, Op. 60, which ends with the key signature of G♯ major exactly as displayed above.[3] The sharps in the key signature of G♯ major here proceed C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, F

. This likely makes more sense than the last example because the notes represented in the key signature increase by a perfect fifth (or decrease by a perfect fourth) from left to right.

. This likely makes more sense than the last example because the notes represented in the key signature increase by a perfect fifth (or decrease by a perfect fourth) from left to right. - The single signs at the beginning are sometimes repeated as a courtesy, e.g. Max Reger's Supplement to the Theory of Modulation, which contains D♭ minor key signatures on pp. 42–45.[4] These have a B♭ at the start and also a B

at the end (with a double-flat symbol), going B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B

at the end (with a double-flat symbol), going B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B .

. - Sometimes the double signs are written at the beginning of the key signature, followed by the single signs. For example, the F♭ key signature is notated as B

, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭. This convention is used by Victor Ewald[5] and by some theoretical works.

, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭. This convention is used by Victor Ewald[5] and by some theoretical works. - However, no. 18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele in B♯ major,[1] it was written as B♯, E♯, A

, D

, D , G

, G , C

, C , F

, F .

.

Tunings other than twelve-tone equal-temperament

In a different tuning system (such as 19 tone equal temperament or any tuning where the number of notes per octave is not a multiple of 12) there will be keys that do require double-sharps or double-flats in the key signature, and no longer have conventional equivalents. For example, in 19 tone equal temperament, the key of B![]() major (9 flats) is equivalent to A♯ major (10 sharps). Thus in non-12-tone tuning systems, keys that are enharmonic in 12-tone equal temperament and its multiples (such as A♭ major vs. G♯ major) must be notated completely differently.

major (9 flats) is equivalent to A♯ major (10 sharps). Thus in non-12-tone tuning systems, keys that are enharmonic in 12-tone equal temperament and its multiples (such as A♭ major vs. G♯ major) must be notated completely differently.

See also

- Closely related key – Musical keys sharing many common tones

- Diatonic function – Musical term

References

- ^ a b Anton Reicha: Practische Beispiele, pp. 52-53.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ "Ewald, Victor: Quintet No 4 in A♭, op 8". imslp. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ John Foulds: A World Requiem, pp. 153ff.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ Max Reger (1904). Supplement to the Theory of Modulation. Translated by John Bernhoff. Leipzig: C. F. Kahnt Nachfolger. pp. 42–45.

- ^ "Ewald, Victor: Quintet No 4 in A♭, op 8", Hickey's Music Center