Multimodal pedagogy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

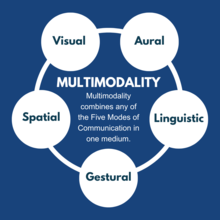

Multimodal pedagogy is an approach to the teaching of writing that implements different modes of communication.[1][2] Multimodality refers to the use of visual, aural, linguistic, spatial, and gestural modes in differing pieces of media, each necessary to properly convey the information it presents.[3][4]

The visual mode conveys meaning via images and the visible elements of a text such as typography and color. The aural mode refers to sound in the form of music, sound effects, silence, etc. The linguistic mode includes written and spoken language. The spatial mode focuses on the physical arrangement of elements in a text. The gestural mode refers to physical movements such facial expressions and how these are interpreted. A multimodal text is characterized by the combination of any two or more modes to express meaning.[5]

Multimodality as a term was coined in the late 20th century,[6] but its use predates its naming, with it being used as early as Egyptian hieroglyphs and classical rhetoric.[7] Compositionists and writing theorists have been exploring how the five modes of communication interact with each other and how multimodality can be used in the teaching of writing since the 20th century.[8]

Multimodal pedagogy encourages the use of these modes as teaching tools in the classroom to facilitate learning. Although lack of experience with new technologies and limited access to resources can make multimodal instruction difficult for teachers,[9] it is important for students to learn to interpret and create meaning across multiple modes of communication in order to navigate a multimodal world.[10]

Background

Some compositionists, such as Jason Palmeri, have suggested that writing has always been multimodal, with writing always containing different modes, such as visual, aural, spatial, and gestural.[8] Multimodal pedagogy in that sense has existed since before multimodality was properly named in the mid-1990s.[6]

Rhetoric began as the art of oral persuasion, and classical rhetoric was always meant to be delivered via voice.[11] In the 1960s, auditory art as it related to writing pedagogy began to be studied by compositionists.[8] In his article “What Do We Mean When We Talk about Voice in Texts?” Peter Elbow introduced his audible voice theory. Elbow’s theory posits that words are multimodal and that readers experience sound in their heads even as they read silently. Audible voice theory argues that reading out loud lets writers understand how voice plays a part in writing and how text sounds to others. This understanding of speech can then improve understanding of communication and writing.[12]

In the 1970s, the Process Theory of Composition focused on writing as a process. Linda Flower and John Hayes studied problem finding and solving, and argued this was a creative cognitive activity that writing and art had in common.[13] Flower and Hayes also argue that writing is multimodal thinking, because writers don’t think in just words. Writing includes the forming of ideas, creation of organization and rhetorical goals, and experiencing the world through our senses.[13]

Kathleen Blake Yancey contends that literacy “is in the midst of tectonic change” and that technology has resulted in an increase in multimodal genres in writing.[14] In one of the National Council of Teachers of English's position statements, they state that all texts are multimodal, and that composing as a whole has changed as a result of technology and its advances.[15] The NCTE asserts that multimodality should be part of definitions for composition and that excluding multimodality is outdated.[15]

Currently, print based literacy has undergone a transformation into hyphenated, plural or multiple literacies, acknowledging the diversity of media and information sources. Both technology and literacy are not mutually exclusive, now existing as a merged vocabulary used in current educational debates.[16] Instructional practices, reading, learning, writing and literacy practices as a whole are being transformed, causing concern amongst teachers and educational educators, to be mediated by microcomputers, the Internet and educational software. The process of reading and writing has shifted, even though the core principles have not, going from print text into multimodal text-image information.[16]

Teachers understand that multimodality composition assignments provide students with valuable opportunities to build their rhetoric skills. An example is an assignment that challenges students to "translate" a text based ethnography to a photo essay, which can cause a change to research ethics.[17] In various scenarios are students able to build the following skills: to properly consider the forms of communication required in every given circumstance, to select resources and materials that will aid in the creation of an effective text, must consider the audience and meet the objectives in correspondence to them, have the finished text be and avenue for improved communication, and to have the text influence positive action.[17]

Goals

Multimodal pedagogy aims to help students express themselves more accurately within their work. This approach allows students to engage deeply with their learning process, possibly increasing their investment in their work by identifying the modes that best suit their subject or personal preferences.[18] With the different kinds of multimodal texts, it allows students to look at other forms of media with the thought of multimodality. Students' individual processing of texts shows different ways of understanding and using multimodality in learning.[18]

Students have four primary learning styles: visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic, each with specific sources of learning.[19] Visual learners are those that get their learning from anything that stimulates their eyes. They primarily use infographics, videos, and illustrations as their source of learning. Aural learners like to use anything they can simply listen to in order to take in information. Their sources of learning mainly come from podcasts, an audiobook, and group discussions. Reading and writing is the most traditional form of multimodal learning. These learners use documents, books, and PDF’s as their primary sources. Lastly, kinesthetic learning is one that gets its learners active. It commonly uses multiple learning types together at once. The main ways of learning are through demonstrations and multimedia presentations.[19]

Multimodal pedagogy aids in enhancing students' comprehension of topics and issues by allowing them to explore information from various perspectives through different modes.[18]

Application to the college writing classroom

Multimodal pedagogy can be applied in many different areas within the college writing classroom. Assignments that incorporate the multimodal modes of communication (visual, spatial, gestural, audio, and linguistic)[3][4] encourage students to think about which method communicates ideas and information in the most efficient way.[20] Technological advances have facilitated access to and creation of new learning materials for students, and multimodal pedagogy makes use of these innovations.[20]

Students who have a harder time engaging with traditional teaching methods may engage better with multimodal materials. Assignments that use multiple modes of communication increase learning and comprehension skills.[20] In addition, multimodal pedagogy allows for the development of multiliteracy skills and modal adaptability using a creative approach.[4]

Multimodal pedagogy can be implemented into required and supplementary learning materials in the form of podcasts, video essays, infographics, or graphic novels (to name a few).[21]

Podcasts help the students learn the importance is lingual communication, which incorporates word choice, tone of delivery, and organization of phrases and ideas.[22] It also teaches the importance of audio — music, sound effects, ambient noise, silence, and volume — when it comes to conveying information.[22]

Graphic novels exemplify the use of the visual communication mode, utilizing color, layout, style, size, and perspective to convey a story or message.[23] The use of visual and graphic novels in the college writing classroom can increase engagement in the material whilst promoting Visual Literacy.[23] Illustrations strengthen information by depicting its content or supplementing it, as seen in The Fragile Framework, an academic comic book published by The International Weekly Journal of Science 'NATURE'.[24]

Zines allow students to engage in multimodal text creation in way that is accessible and inexpensive. Students are able to cut and paste images and text into pamphlet pages requiring that they make choices regarding the visual, linguistic, and spatial aspects of the text and examine these modes in relation to another.[25]

Educational institutions have implemented multimodal pedagogy directly through curriculum design.[10] Universities such as Iowa State and Georgia Tech use a WOVE curriculum in their composition courses. The acronym stands for written, oral, visual, and electronic communication. This curriculum recognizes the interconnectedness of these communicative modes and is designed to prepare students with a range of literacy skills that extends across multiple modes and media.[26]

Challenges

Inexperience with new media poses a challenge for teachers in multimodal classrooms.[9] Some teachers, such as Bremen Vance of Iowa State University, express anxiety and discomfort in incorporating new modes and technologies as they lack the skills to confidently engage with these, let alone guide students in their engagement.[26] The rapid development of new media available to teachers further complicates the task of staying up to date and equipped with the skills to utilize these. While the multimodal pedagogical approach has expanded what qualifies as writing and how teachers can go about its instruction, thorough knowledge and planning is required in order to be effectively implemented.[10] Writing instructors need to be able to contextualize their use of multimodal texts and lead students to rhetorically analyze how these create meaning.[9]

Lack of resources has limited the ability of public school teachers to integrate new technologies that facilitate multimodal learning in their classrooms. Often times, they are forced to resort to older technologies and poorly functioning equipment such as overhead projectors and art supplies.[10]

References

- ^ Sanders, Jennifer; Albers, Peggy (2010). "Multimodal Literacies: An Introduction". Literacies, the Arts, and Multimodality. NCTE. ISBN 978-0814132142.

- ^ Halliday, M.A.K. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar (3rd ed.). Hodder Education Publishers. ISBN 978-0340761670.

- ^ a b Murray, Joddy (2014). "Composing Multimodality". In Lutkewitte, Claire (ed.). Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook (1st ed.). Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-1457615498.

- ^ a b c GRAPIN, SCOTT (2019). "Multimodality in the New Content Standards Era: Implications for English Learners". TESOL Quarterly. 53 (1): 30–55. ISSN 0039-8322.

- ^ Varaporn, Savika; Sitthitikul, Pragasit (April 2019). "Effects of multimodal tasks on students' critical reading ability and perceptions" (PDF). Reading in a Foreign Language. 31 (1): 81–108.

- ^ a b Jewitt, Carey; Bezemer, Jeff; O'Halloran, Kay (2016). Introducing Multimodality (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415639262.

- ^ Welch, Kathleen E.; Barrett, Edward (1999). Electric Rhetoric: Classical Rhetoric, Oral ism, and a New Literacy. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262519472.

- ^ a b c Palmeri, Jason (2012). Remixing Composition: A History of Multimodal Writing Pedagogy. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-3089-8. OCLC 1039082032.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Josephine; Scott, Anne; Walsh, Maureen (August 2010). "Pedagogy in the multimodal classroom: an analysis of the challenges and opportunities for teachers". Teachers and Teaching. 16 (4): 477–489. doi:10.1080/13540601003754871. ISSN 1354-0602.

- ^ a b c d Albers, Peggy (2006). "Imagining the Possibilities in Multimodal Curriculum Design". English Education. 38 (2): 75–101. ISSN 0007-8204.

- ^ Corbett, Edward P.J. (1967). "A New Look at Old Rhetoric". In Gorell, Robert M. (ed.). Rhetoric: Theories for Application. Champaign, IL: NCTE. ISBN 978-0814141373.

- ^ Elbow, Peter (1994). What Do We Mean When We Talk about Voice in Texts?. Urbana, IL: NCTE. ISBN 978-0814156346.

- ^ a b Flower, Linda; Hayes, John R. (1980). "The Cognition of Discovery: Defining a Rhetorical Problem". College Composition and Communication. 31 (1): 21–32. doi:10.2307/356630. ISSN 0010-096X.

- ^ Yancey, Kathleen Blake (2004). "Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key". College Composition and Communication. 56 (2).

- ^ a b "Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing". National Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ a b Luke, Carmen (2003). "Pedagogy, Connectivity, Multimodality, and Interdisciplinarity". Reading Research Quarterly. 38 (3): 397–403. ISSN 0034-0553.

- ^ a b "Teaching Multimodal Composition | U-M LSA Sweetland Center for Writing". lsa.umich.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ a b c Bridging the Multimodal Gap: From Theory to Practice. University Press of Colorado. 2019. ISBN 978-1-60732-796-7.

- ^ a b Caroline (2019-10-24). "Multimodal Learning: Engaging Your Learner's Senses". LearnUpon. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ a b c Arms, Valarie M. (2012). "Hybrids, Multi-modalities and Engaged Learners: A Composition Program for the Twenty-First Century". Rocky Mountain Review. 66 (2): 194–211. ISSN 1948-2825.

- ^ Bouchey, Bettyjo; Castek, Jill; Thygeson, John (2021), Ryoo, Jungwoo; Winkelmann, Kurt (eds.), "Multimodal Learning", Innovative Learning Environments in STEM Higher Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Looking Forward, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 35–54, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58948-6_3, ISBN 978-3-030-58948-6, retrieved 2024-03-28

- ^ a b "Adapting the Framework: Podcasts | U-M LSA Sweetland Center for Writing". lsa.umich.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ a b Dallacqua, Ashley K. (2012). "Exploring Literary Devices in Graphic Novels". Language Arts. 89 (6): 365–378. ISSN 0360-9170.

- ^ Monastersky, Richard; Sousanis, Nick (2015-11-01). "The fragile framework". Nature. 527 (7579): 427–435. doi:10.1038/527427a. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Buchanan, Rebekah (2012). "Zines in the Classroom: Reading Culture". The English Journal. 102 (2): 71–77. ISSN 0013-8274.

- ^ a b Vance, Bremen (2017). "No Teacher is an Island: Strategies for Enacting Multimodal Pedagogies". The CEA Forum. 46 (2): 127–140 – via MLA International Bibliography.

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (April 2023) |