Philip Johnson

Philip Johnson | |

|---|---|

Johnson aged 95, with a model of a privately commissioned sculpture (2002) | |

| Born | Philip Cortelyou Johnson July 8, 1906 |

| Died | January 25, 2005 (aged 98) New Canaan, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Harvard Graduate School of Design |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Pritzker Prize (1979) AIA Gold Medal (1978) |

| Buildings | Glass House, Seagram Building's 2 restaurants, 550 Madison Avenue, IDS Tower, PPG Place, Crystal Cathedral |

Philip Cortelyou Johnson (July 8, 1906 – January 25, 2005) was an American architect who designed modern and postmodern architecture. Among his best-known designs are his modernist Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut; the postmodern 550 Madison Avenue in New York City, designed for AT&T; 190 South La Salle Street in Chicago; the Sculpture Garden of New York City's Museum of Modern Art; and the Pre-Columbian Pavilion at Dumbarton Oaks. His January 2005 obituary in The New York Times described his works as being "widely considered among the architectural masterpieces of the 20th century".[1]

In 1930, Johnson became the first director of the architecture department of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. There he arranged for visits by Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier and negotiated the first American commission for Mies van der Rohe, after he fled Nazi Germany. In 1932, he organized with Henry-Russell Hitchcock the first exhibition dedicated to modern architecture at the Museum of Modern Art, which gave name to the subsequent movement known as International Style. In 1934, Johnson resigned his position at the museum.

During the 1930s, Johnson became an ardent admirer of Adolf Hitler, openly praised the Nazi Party, and espoused antisemitic views.[2][3][4] He wrote for Social Justice and Examiner, where he published an admiring review of Hitler's Mein Kampf.[5] In 1939, as a correspondent for Social Justice, he witnessed Hitler's invasion of Poland, which he later described as "a stirring spectacle".[6] In 1941, after the U.S. entered the war, Johnson abruptly quit journalism, organizing anti-Fascist league at Harvard Design School. He was investigated by the FBI, and was eventually cleared for military service.[1] He evaded indictment and jail, according to some critics, because of his social connections.[7] Years later he would refer to these activities as "the stupidest thing I ever did [which] I never can atone for".

In 1978, he was awarded an American Institute of Architects Gold Medal. In 1979, he was the first recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.[8] Today his skyscrapers are prominent features in the skylines of New York, Houston, Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Madrid, and other cities.

Early life and career

Johnson was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on July 8, 1906, the son of a lawyer, Homer Hosea Johnson (1862–1960), and the former Louisa Osborn Pope (1869–1957), a niece of Alfred Atmore Pope and a first cousin of Theodate Pope Riddle. He had an older sister, Jeannette, and a younger sister, Theodate. He was descended from the Jansen family of New Amsterdam. His ancestors include the Huguenot Jacques Cortelyou, who laid out the first town plan of New Amsterdam for Peter Stuyvesant. He grew up in New London, Ohio.[9] He had a stutter and was diagnosed with cyclothymia.[10] He attended the Hackley School in Tarrytown, New York, then studied as an undergraduate at Harvard University where he focused on learning Greek, philology, history and philosophy, particularly the work of the Pre-Socratic philosophers.

Upon completing his studies in 1930,[10] he made a series of trips to Europe, particularly Germany, where his family had a summer house. He visited the landmarks of classical and Gothic architecture, and joined Henry-Russell Hitchcock, a prominent architectural historian, who was introducing Americans to the work of Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and other modernists. In 1928, he met German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was at the time designing the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. The meeting formed the basis for a lifelong relationship of both collaboration and competition.[1][11]

Johnson had a substantial fortune, largely due to his father's successful investment in Alcoa, the Aluminum Company of America.[12] With this fortune, in 1930 he financed the new architecture department of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and in 1932 he was named its curator. As curator he arranged for American visits by Gropius and Le Corbusier, and negotiated the first American commission for Mies van der Rohe. In 1932, working with Hitchcock and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., he organized the first exhibition on Modern architecture at the Museum of Modern Art.[13] The show and their simultaneously published book International Style: Modern Architecture Since 1922, published in 1932, played a seminal role in introducing modern architecture to the American public.[14]

When the rise of the Nazis in Germany forced the modernists Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe to leave Germany, Johnson helped arrange for them to come to work in the United States.[15] He created a small organization called the Gray Shirts, styled after the Nazi Brownshirts.[10]

The amount of power he yearned for was inversely proportional to the amount he actually attained. In politics, he proved to be a trifler, the dilettante he earlier feared himself to be, a model of futility who sought to find a messiah or to pursue messianic ends but whose most lasting following turned out to be the agents of the FBI—who themselves finally grew bored with him. In short, he was never much of a political threat to anyone, still less an effective doer of either political good or political evil.

Politics and journalism

In December 1934, Johnson abruptly left the Museum of Modern Art and began pursuing a career in journalism and politics. He first became a supporter of Huey Long, the populist governor of Louisiana. He tried and failed to recruit Long to join the National Party, which he founded.[10] Johnson unsuccessfully ran for representative of New London in the Ohio state legislature.[10] After Long was assassinated in 1935, Johnson became a correspondent for Social Justice, the newspaper of the radical-populist and anti-Semitic Father Charles Coughlin. Johnson traveled to Germany and Poland as a correspondent, where he wrote admiringly about the Nazis.[17][13][18][19]

In Social Justice, Johnson expressed, as The New York Times later reported, "more than passing admiration for Hitler".[1] In the summer of 1932 Johnson attended one of the Nuremberg Rallies in Germany and saw Hitler for the first time. Years later he would describe the event to his biographer, Franz Schulze: "You simply could not fail to be caught up in the excitement of it, by the marching songs, by the crescendo and climax of the whole thing, as Hitler came on at last to harangue the crowd". He told of being thrilled at the sight of "all those blond boys in black leather" marching past the Führer.[16]: 89–90 Sponsored by the German government, he traveled on a press tour which covered the invasion of Poland in 1939. Schulze dismissed these early political activities as inconsequential, concluding they merited "little more substantial attention than they have gained" and his politics "were driven as much by an unconquerable esthetic impulse as by fascist philosophy or playboy adventurism".[16]: 144, 146 [20][17]

Architecture school and Army service

In 1941, at the age of 35, Johnson abandoned politics and journalism and enrolled in the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he studied with Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, who had recently fled from Nazi Germany.[1] In 1941, Johnson designed and built his first building, a house at 9 Ash Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The house, strongly influenced by Mies van der Rohe, has a wall around the lot which merges with the structure.[21] It was used by Johnson to host social events and was eventually submitted as his graduate thesis; he sold the house after the war, and it was purchased by Harvard in 2010[22] and restored by 2016.[23]

In 1942, while still a student of the architecture school, Johnson tried to enlist with Naval Intelligence, and then for a federal job, but was rejected both times. In 1943, after his graduation from Harvard, he was drafted to the Army and was sent to Fort Ritchie, Maryland, to interrogate German prisoners of war.[24] He was investigated by the FBI for his involvement with the German government, Coughlin and Lawrence Dennis, an American fascist economist, and was cleared for continued military service.[25][24] After the trial of Dennis and his collaborators, Johnson was relieved of his interrogation duties and transferred to Fort Belvoir, Virginia,[26] where he spent the rest of his military service doing routine duties.[24]

Early Modernist period (1946–1960)

-

The Glass House (1949)

-

Interior of the Glass House (1949)

-

Farnsworth House by Mies (designed 1945–7) for comparison

-

The Four Seasons' restaurant of Seagram Building in its original form (1956)

In 1946, after he completed his schooling and his military service, Johnson returned to the Museum of Modern Art as a curator and writer. At the same time, he began working to establish his architectural practice. He built a small house, influenced by the work of Mies, in Sagaponack, Long Island. In 1947, he published the first monograph in English on the architecture of Mies.

In 1947, he curated the first exhibition of modern architecture of the Museum of Modern Art including a model of the glass Farnsworth House of Mies.[27]

In 1949, he began building a new residence, the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, that was completed in 1949. It was clearly influenced by Farnsworth House of Mies, an influence which Johnson never denied, but looked quite different.[15]

The Glass House is a 56-foot by 32-foot glass rectangle, sited at the edge of a crest on Johnson's estate overlooking a pond. The building's sides are glass and charcoal-painted steel; the floor, of brick, is not flush with the ground but sits 10 inches above. The interior is an open space divided by low walnut cabinets; a brick cylinder contains the bathroom and is the only object to reach floor to ceiling. The New York Times described it in 2005 as "one of the 20th century's greatest residential structures. "Like all of Johnson's early work, it was inspired by Mies, but its pure symmetry, dark colors and closeness to the earth marked it as a personal statement; calm and ordered rather than sleek and brittle."[1]

Johnson continued to add to the Glass House estate during each period of his career. He added a small pavilion with columns by the lake in 1963, an art gallery set into a hillside in 1965, a postmodern sculpture gallery with a glass roof in 1970; a castle-like library with a rounded tower in 1980; and a concrete block tower dedicated to his friend Lincoln Kirstein, the founder of the New York City Ballet; a chain-link "ghost house" dedicated to Frank Gehry.[1]

After completing the Glass House, he completed two more houses in New Canaan in a style similar to the Glass House; the Hodgson House (1951) and the Wiley House (1953). In New York City, He designed two major modernist additions to the Museum of Modern Art; a new annex, and, to complement it, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden (1953)[15]

In 1954–56, he made the pro bono design for Congregation Kneses Tifereth Israel, a synagogue for a conservative Jewish congregation in Port Chester, New York. It had a simple interior and a ceiling of curving plaster panels. [28]

In 1957, Johnson designed the Nahal Soreq nuclear reactor in Israel at the invitation of Shimon Peres.

Johnson joined Mies van der Rohe as the architect of record (Mies did not have NY license) for the 39-story Seagram Building (1956). Johnson was pivotal in steering the commission towards Mies by working with Phyllis Lambert, the daughter of the CEO of Seagram. The commission resulted in the iconic bronze-and-glass tower on Park Avenue. The building was designed by Mies, and the interiors of the Four Seasons and Brasserie restaurants (later redesigned), as well as office furniture were designed by Johnson.[29] In December 1955, the city of New York denied an architect's permit to Mies. He moved back to Chicago and put Johnson fully in charge of construction. Mies returned in late 1956 and finished the building.

In 1989, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Seagram's exterior, lobby, and The Four Seasons Restaurant as official city landmarks. In 2006, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Late Modernism (1960–1980)

-

Monastery building at St. Anselm's Abbey in Washington DC (1960)

-

The David Koch Theater at Lincoln Center in New York City (completed 1964)

Throughout the 1960s, Johnson continued to create in the vocabulary of the modernist style, designing geometrical theatres, a monastery, art galleries and gardens. The Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute (1960) is a good example of his work in the period; it is supported by eight external ferro-concrete piers, or two on each side. The exterior structural members are clad in bronze and "black" Canadian granite. The windowless cube is set above the office areas, which recessed in a dry moat, giving a "floating" effect.[31] A model of the building was exhibited in the United States Pavilion at the Brussels' World's Fair of 1958,as an example of the new trends in American architecture. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.

Another major project of the period was the Atrium of the David H. Koch Theater (formerly the New York State Theatre, the home of the New York City Ballet, at Lincoln Center in New York.

-

The Johnson Building at Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts (1972) after its 2016 renovation

-

Pennzoil Place in Houston, Texas (1970–1976)

-

Pennzoil Place from above

-

Paley Center for Media, New York (1991)

In 1967, Johnson entered a new phase of his career, founding a partnership with architect John Burgee. He began to design office building complexes for large corporations. The most prominent of these was Pennzoil Place (1970–76) in Houston, Texas. The two towers of Pennzoil Place have sloping roofs covering the top seven floors and are trapezoidal in form, planned to create two large triangual areas on the site, which are occupied with glass-covered lobbies designed like greenhouses. This idea was widely copied in skyscrapers in other cities.[32]

The new building of the Boston Public Library (1972), known as the Johnson building, adjoins the original Boston library built in the 19th century by the celebrated firm of McKim, Mead & White. Johnson harmonised his building with the original landmark by using similar proportions and the same pink Milford granite.

-

The Fort Worth Water Gardens, in Fort Worth, Texas (1974)

-

The spiral chapel in Thanks-Giving Square in Dallas,Texas (1977)

In the late 1970s, Johnson combined architecture and landscape architecture to create two imaginative civic gardens. The Fort Worth Water Gardens opened in 1974, is an urban landscape where visitors experience water in distinct ways. The gardens cover 4.3-acres (1.7 hectare), and comprise three very different kinds of water features; One offers a quiet meditation pool, surrounded with cypress trees and high walls, with a thin sheet of water cascading downward to the pool, making the sound of a rain shower. The second pool is an aerating pool with multiple illuminated spray fountains, beneath a grove of oak trees. The third fountain is the Active Pool, which challenges fit visitors to walk down 38 feet (12 meters) to the pool at the bottom, with water cascading all around them.[33]

In 1977, Johnson completed a much quieter garden in Dallas, Thanks-Giving Square. It features a non-denominational chapel in a spiral form, a meditation garden and cascading fountains, tucked between buildings in the center of the city.

Postmodern period (1980–1990)

-

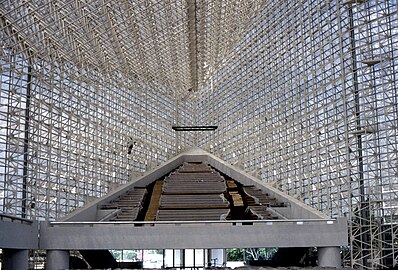

The Crystal Cathedral (finished 1980)

-

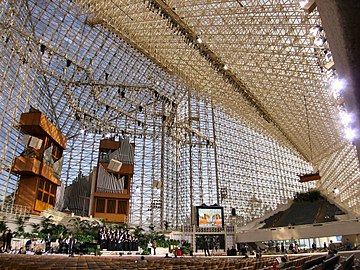

Interior of the Crystal Cathedral

-

Interior of the Cathedral in 2004

In 1980, Johnson and Burgee completed a cathedral in a dramatic new style: the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California, is a soaring glass megachurch originally built for the Reverend Robert H. Schuller.[34] The interior can seat 2,248 persons. It takes the form of a four-pointed star, with free-standing balconies in three points and the chancel in the fourth. The cathedral is covered with more than ten thousand rectangular pieces of glass. The Glass panels are not bolted, but glued to the structure, with a silicon based glue, to give it greater ability to resist Southern California earthquakes.[35] Johnson and Burgee designed it to withstand an earthquake of magnitude 8.0.[36] The tower was added in 1990.

The cathedral quickly became a Southern California landmark, but its costs helped drive the church into debt. When the church declared bankruptcy in 2012, it was purchased by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange and became the Roman Catholic cathedral for Orange County.

Working with John Burgee, Johnson did not confine himself to a single style, and was comfortable mixing elements of modernism and postmodernism. For the Cleveland Play House, he built a romanesque brick structure; His skyscrapers in the 1980s were clad in granite and marble, and usually had some feature borrowed from historic architecture. In New York he designed the Museum of Television and Radio, (now the Paley Center for Media) (1991).

-

550 Madison Avenue (1982)

-

Top of 550 Madison Avenue

-

Window of 550 Madison Avenue

-

Entrance of 550 Madison Avenue

In 1982, working in collaboration with John Burgee, he finished one of his most famous buildings, 550 Madison Avenue, (first known as AT&T Building, then the Sony building before taking its present name). Built between 1978 and 1982, it is a skyscraper with an eight-story high arched entry and a split pediment at the top which resembles an enormous piece of 18th-century Chippendale furniture. It was not the first work of Postmodern architecture, as Robert Venturi and Frank Gehry had already built smaller scale postmodern buildings, and Michael Graves had completed the Portland Building (1980–82) in Portland, Oregon, two years earlier; But the building's Manhattan location, size and originality made it the most famous and recognizable example of postmodern architecture.[37] It was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2018.

-

TC Energy Center (Formerly Bank of America Center) in Houston, Texas (1983)

-

The TC Energy Center, Houston (1983)

-

PPG Place, Pittsburgh, (1984)

Between 1979 and 1984, Johnson and Burgee built PPG Place the postmodern headquarters of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company. It is a complex of six buildings within three city blocks, covering five and a half acres. The centerpiece is the forty-story tower, One PPG Place,which has a crown of spires at the corners which suggest the neogothic tower of the Houses of Parliament in London. During the 1980s Johnson and Burgee completed a series of other notable postmodern landmarks. The TC Energy Center (Formerly Republic Bank Center, later, Bank of America Center), in Houston (1983), was the first postmodern skyscraper in the Houston skyline. Fifty-six Stories high, it has two setbacks creating what appear to be three different buildings, one against the other. The Three triangular gables were inspired by Flemish Renaissance architecture.[37] The interior and exterior are covered with rough-textured red granite, which also covers the surrounding sidewalks.[38]

-

Hines College of Architecture at the University of Houston (1985)

-

The elliptical Lipstick Building in Manhattan, (1986)

-

The concrete tower and cupola of 400 West Market in Louisville, Kentucky (1993)

The new building for the Hines College of Architecture (1985) of the University of Houston paid homage to forms drawn from earlier periods of architectural history, using modern materials, construction methods and scale. The facade of the Hines building resembles, on a larger scale, the neoclassic facades of the French architect Claude Nicolas Ledoux.

400 West Market (1993), in Louisville, Kentucky is a thirty-five story office tower built of reinforced concrete rather than the typical steel. It is topped by a concrete cupola, a vestige of the building's original owner and builder, Capital Holding.[39]

In 1986, Johnson and Burgee had moved their offices into one of their new buildings, the elliptical Lipstick Building at 885 Third Avenue in New York, nicknamed because of its resemblance to the color and shape of a stick of lipstick. A feud was beginning between the two architects, with Burgee demanding greater recognition. [1]

As their business flourished and number of clients grew, the feud between Burgee and Johnson continued to grow. In 1988, the firm's name was changed to John Burgee Architects with Johnson as the "design consultant". In 1991, Johnson responded by establishing his own firm. The feud ended badly for Burgee; he was saddled with all of the debts of the firm, while Johnson no longer had any responsibility. Burgees was eventually forced to declare bankruptcy, and to retire, while Johnson continued to get commissions.[1]

Later career and buildings (1991–2005)

-

Ally Detroit Center in Detroit, Michigan (1991–1993)

-

191 Peachtree Tower in Atlanta (1991)

-

Chapel of St. Basil at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas (1992)

-

"Da Monsta" entry pavilion for the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut (1995)

-

Gate of Europe towers in Madrid, Spain (1989–96)

-

190 South LaSalle in Chicago, Illinois (1987)

After four years as a solo practitioner, Johnson invited Alan Ritchie to join him as a partner. Ritchie had been a partner for many years in the Johnson-Burgee office and was the partner-in-charge of the AT&T building and the 190 South LaSalle office building, a skyscraper designed as an homage to the demolished Masonic Temple of Chicago. In 1994, they formed the new practice of Philip Johnson-Alan Ritchie Architects. During the next ten years, they worked closely together and explored new directions in architecture, designing buildings as sculptural objects.

The Gate of Europe in Madrid (1989 - 1996) was originally a collaboration with Burgee, and one of his rare works in Europe. It features two office buildings leaning toward each other, the first example of this style, which spread to America. The towers are twenty-six stories each, and both lean by 15 degrees from vertical.

191 Peachtree Tower in Atlanta was a project begun with Burgee. It is composed of two fifty-story towers joined, and crowned with two classical pavilions.[40]

The Comerica Tower (1991-1993) was also begun with Burgee. Like their earlier Postmodern works, it featured elements borrowed from historical architecture, particularly the triangular gables, borrowed from Renaissance Flemish architecture. It is the second tallest building in the state of Michigan.

The Chapel of St. Basil at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas (1992) is notable late work. The design includes a domed chapel, a campanile, and a mediation garden, a labyrinth. Its structure is combination of the basic forms; a cube, a sphere, and a plane. The cube contains the worship area, beneath a semi-sphere, which is presented as the symbolic opening to heaven. The vertical rectangular granite plane divides the church and opens the chapel to light. During daytime the interior is lit entirely with natural light.[41]

In 1995, Johnson added a postmodern element to his own residence, the Glass House. This was a new entry pavilion in a sculptural form, which he called the "Monsta", or "Monster".

Other late works include the Cathedral of Hope in Dallas, the Habitable Sculpture (a 26-story apartment tower in lower Manhattan); The Children's Museum in Guadalajara, Mexico, and The Chrysler Center.

-

The Urban Glass House condominiums in New York (2006)

-

The Ware Center in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (2008)

The Urban Glass House in lower Manhattan was one of last designs with Alan Ritchie, and was not completed after Johnson's death. It is a condominium building in lower Manhattan whose form was inspired by Johnson's most famous early work, the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut.

The final building he designed with Richie was the Pennsylvania Academy of Music building in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, which was completed in 2008, three years after his death.[42][43]

Honors

In 1978, Johnson was awarded an American Institute of Architects Gold Medal. In 1979, he became the first recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize the most prestigious international architectural award.[8]

In 1991, Johnson received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[44]

Personal life

Johnson was gay. He came out publicly in 1993, and was regarded as "the best-known openly gay architect in America".[45]

In 1934, Philip Johnson began his first serious relationship with Jimmie Daniels, a cabaret singer. The relationship lasted one year.[46]

Johnson died in his sleep at his Glass House retreat on January 25, 2005, at the age of ninety-eight. His partner of 45 years, David Whitney,[47][48][49][50] died later that year at age 66.[51]

Johnson was among the public figures at the core of the effort to save Olana, the home of Frederic Edwin Church, before it was dedicated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and subsequently became a New York State Historic Site.[52][53]

In his will Johnson left his residential compound to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It is now open to the public.

Art collection and archives

As an art collector Johnson had an eclectic eye. He supported avant-garde movements and young artists often before they became widely known. His collection of American art was strong in Abstract expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, Neo-Dada, Color Field, Lyrical Abstraction, and Neo-Expressionism and he often donated important works from his collection to institutions like MoMA, and other important private museums and University collections like the Norton Simon Museum, the Sheldon Museum of Art and the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University among many others.[1]

Johnson's publicly held archive, including architectural drawings, project records, and other papers up until 1964 are held by the Drawings and Archives Department of Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, the Getty, and the Museum of Modern Art.

Controversy over political activities

Reviewing Franz Schulze's biography of Johnson, Kazys Varnelis wrote that "between 1932 and 1940, Johnson was an antisemite, fascist sympathizer, and active propagandist for the Nazi government."[18] According to Varnelis, "Johnson makes no apologetic gesture toward his past behavior unless he is confronted by direct questioning, nothing even as paltry as an open letter accounting for and regretting his past actions and condemning the motives that led him to them".[18] Johnson's activities included organizing political rallies for populist Huey Long; funding figures such as the right-wing agitator Joe McWilliams and his "Christian Mobilizers";[54] and writing for three periodicals, including Charles Coughlin's Social Justice, whose "almost every issue contained articles about the 'Jewish conspiracy' or about destructive economic forces led by figures with Jewish names".[55]

Because his family had a home in Germany and spent their summers there, Johnson traveled there frequently. As a Social Justice correspondent, he covered the huge Nazi rally at Nuremberg and the 1939 invasion of Poland with approval. The American correspondent William L. Shirer, traveling with him on the Nazi-sponsored press tour, labeled him in Berlin Diary, as "the American fascist" and suspected him of spying for the Germans.[17][56] On the same tour, three weeks after Poland fell to the Nazis, Johnson, with Shirer, "was with German troops at the front as the guest of the Propaganda Ministry".[57] He wrote to a friend that "The German green uniforms made the place look gay and happy... There were not many Jews to be seen. We saw Warsaw burn and Modlin being bombed. It was a stirring spectacle."[11][58]

In his Social Justice report on his trip to Poland, Johnson declared that the German victory amounted to an unmitigated triumph for the Polish people and that nothing in the war's outcome need concern Americans. Johnson went on to say that German forces had not significantly harmed Polish civilians, and said that "99 percent of the towns I visited since the war are not only intact but full of Polish peasants and Jewish shopkeepers." He said reports of Nazi mistreatment of Poles was "misinformed".[17] Referring to political developments in France, Johnson wrote in Social Justice that "Lack of leadership and direction in the state has let the one group get control who always gain power in a nation's time of weakness—the Jews". In 1940 Johnson quit journalism and distanced himself from politics.

In April 1942, on reports that Johnson might be working in Colonel Donovan's Office of the Coordinator of Information, the United States Assistant Attorney General James H. Rowe wrote to Director Hoover, saying, "I can think of no more dangerous man to have working in an agency which possesses so many military secrets."[17][59] Johnson was later investigated by the FBI, but no charges were brought against him, and he was cleared for military service.[16][1]

Johnson was inducted into the U.S. Army in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on March 12, 1943, but controversy continued. His name arose again in the so-called "Great Sedition Trial" of 1944 through his former contacts in the 1930s with its main target, the former diplomat and economist Lawrence Dennis, who in the 1930s supported fascist economics as an alternative to capitalism. Dennis was charged with sedition, or advocating the forcible overthrow of the U.S. government, under the Smith Act. Johnson was accused of "close and steady contact" with Dennis in the spring of 1938, and providing financial support towards publishing Dennis's 1940 book The Dynamics of War and Revolution. Johnson had already testified in 1942 in the government case against another former associate, the German poet and journalist George Sylvester Viereck in 1942.[16] The ongoing federal case against Dennis, an FBI investigation, and a congressional investigation investigated about 30 people, including Johnson, but in the end he was not charged.[60] Johnson was formally asked to appear at trial as a witness, and—by his own account—was speaking to prosecutor O. John Rogge,[16] but after Judge Edward C. Eicher died of a heart attack a mistrial was declared and the case was dropped.

In 1993, when asked by Vanity Fair about his past political views, he said, "I have no excuse (for) such unbelievable stupidity. ... I don't know how you expiate guilt."[18][61][60]

In 1956, he donated a design for Congregation Kneses Tifereth Israel in Port Chester, New York. Architecture professor Anat Geva observed in a paper that "all critics agree that his design of the Port Chester Synagogue can be considered as his attempt to ask for forgiveness."[19]

He discussed his trips to Germany and his infatuation with fascism in a 1996 interview with Charlie Rose. He said, "It was the stupidest thing I ever did, and I never forgive myself and I never can atone for it. There's nothing I can do... That's been torture to me ever since."[62] He admitted to Rose that, while he had "difficulty" with Franklin D. Roosevelt because of his inability to achieve what he set out, he "worshiped the man" and "voted for him four times."[62] Replying to Rose asking if he liked "strong figures", he said "Sure do. I like good architects that are strong, like Gehry."[62]

In 2018, Nikil Saval wrote in The New Yorker that "Johnson would later describe Hitler as 'a spellbinder'; in 1964, well after he had been forced to abjure his Nazi past, he insisted in letters that Hitler was 'better than Roosevelt.'"[13]

In 2020, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the wave of place name changes that followed, the Johnson Study Group—a group of 40 architects, designers, and educators—approached the Museum of Modern Art asking that honors given to Johnson be removed from public view, citing his "commitment to white supremacy", spread of Nazi publications, involvement with American fascist politics, and "effective segregation" of the architectural collection at the museum. "When it comes to racist urban planning policies in the 20th century and a deeply Eurocentric antiblack archive of American architecture," V. Mitch McEwen said, "MoMA under white supremacist Philip Johnson did largely create the problem. It innovated white supremacy in architecture ... where under his leadership not a single work by any Black architect or designer was included."[63][64][65]

In a 2020 article in Elle Decor magazine, articles editor Charles Curkin asked Pritzker Prize laureate Balkrishna Doshi if the architecture world was due for a reckoning, citing the Museum of Modern Art's chief architecture and design curatorship still being named after Johnson. Doshi replied that "Life itself is due for a reckoning, and architects must give respect to life."[66]

In 2020, Johnson's name was dropped from the Harvard University Philip Johnson Thesis House, which was designed by Johnson.[67] Sarah Whiting, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, announced the change on December 5, 2020, citing Johnson's "widely documented white supremacist views and activities."[67]

Quotations

- "I got everything from someone. Nobody can be original. As Mies van der Rohe said, 'I don't want to be original. I want to be good.'"[68]

- "Don't build a glass house if you're worried about saving money on heating."[68]

- "Everybody should design their own home. I'm against architects designing homes. How do I know that you want to live in a picture-window Colonial? It's silly, but you might want to. Who am I to say?"[68]

- "Architecture is the arrangement of space for excitement".[68]

- "Storms in this house (The Glass House) are horrendous but thrilling. Glass shatters. Danger is one of the greatest things to use in architecture."[68]

- "A room is only as good as you feel when you're in it".[68]

- "Merely that a building works is not sufficient."[69]

- "We still have a monumental architecture. To me, the drive for monumentality is as inbred as the desire for food and sex, regardless of how we denigrate it."[1]

In popular culture

Johnson is mentioned (along with fellow architect Richard Rogers) in the song "Thru These Architect's Eyes" on the album Outside (1995) by David Bowie.[70]

He appears in Nathaniel Kahn's My Architect, a 2003 documentary about Kahn's father, Louis Kahn.[71]

Philip Johnson's Glass House, along with Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House, was the subject of Sarah Morris's 2010 film Points on a Line. Morris filmed at both sites over the course of several months, among other locations including The Four Seasons Restaurant, the Seagram Building, Mies van der Roheʼs controversial 860–880 Lake Shore Drive Apartments, and Chicagoʼs Newberry Library.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Goldberger, Paul (January 27, 2005). "Obituary: Philip Johnson, Architecture's Restless Intellect, dies at 98". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ Saval, Nikil (December 12, 2018). "Philip Johnson, the Man Who Made Architecture Amoral". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

Johnson was an anti-Semite and a strong proponent of ruling-class power. (...) Indeed, it is difficult to think of an American as successful as Johnson who indulged a love for Fascism as ardently and as openly. (...) Johnson would later describe Hitler as "a spellbinder"; in 1964, well after he had been forced to abjure his Nazi past, he insisted in letters that Hitler was "better than Roosevelt."

- ^ Budds, Diana (December 1, 2020). "Artists to MoMA: Take Down Philip Johnson's Name". Curbed. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

Johnson described attending Nazi rallies in Germany as "exhilarating" and attempted to found a fascist political party in the United States.

- ^ Bahr, Sarah (December 3, 2020). "Artists Ask MoMA to Remove Philip Johnson's Name, Citing Racist Views". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

He also championed racist and white supremacist viewpoints in his younger years. Johnson's Nazi sympathies, for example, have been well documented (...)

- ^ Lamster, Mark (October 31, 2018). "Was Architect Philip Johnson a Nazi Spy?". New York Magazine. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Nast, Condé (December 3, 2020). "Artists Are Calling on MoMA to Remove Philip Johnson's Name". Architectural Digest. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Nast, Condé (April 4, 2016). "Famed Architect Philip Johnson's Hidden Nazi Past". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

How did Johnson, virtually alone among his Fascist associates, manage to avoid indictment? The answer may lie in the influence of powerful friends. One man in particular could well have been influential: (...) Nelson Rockefeller, who knew Johnson well from his New York days.

- ^ a b Goldberger, Paul (May 23, 1979). "Philip Johnson Awarded $100.000 Pritzker Prize." Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ "Forms Under Light". The New Yorker. May 15, 1977. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Maddow, Rachel (2023). Prequel: an American fight against fascism (First ed.). New York: Crown. pp. 2–56. ISBN 978-0-593-44451-1.

- ^ a b Saint, Andrew (January 28, 2005). "Philip Johnson (obit) – Flamboyant postmodern architect whose career was marred by a flirtation with nazism". Guardian. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Mashiach, Itay (June 14, 2024). "The Nazi who built Israel a nuclear reactor".

- ^ a b c Saval, Nikil (December 12, 2018). "Philip Johnson, the Man Who Made Architecture Amoral". Newyorker.com. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 573.

- ^ a b c Taschen 2016, p. 314.

- ^ a b c d e f Schulze, Franz (1996). Philip Johnson: Life and Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-74058-4. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Wortman, Marc. "Famed Architect Philip Johnson's Hidden Nazi Past". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Varnelis, Kazys, Cornell University (November 1994). "We Cannot Not Know History: Philip Johnson's Politics and Cynical Survival". Journal of Architectural Education. 49 (2). Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc.: 92–104. doi:10.2307/1425400. JSTOR 1425400. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Geva, Anat. "An Architect Asks For Forgiveness: Philip Johnson's Port Chester Synagogue" (PDF). Symposium of Architecture, Culture and Spirituality. ACS Forum. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ His involvement with fascism and the Nazi party was documented in Marc Wortman's 2016 book 1941: Fighting the Shadow War. It was excerpted by Vanity Fair magazine.

- ^ Cahill, Frank M.; Harrington, Cleo M. (March 2, 2017). "If Only We Could See It: Philip Johnson's Mystery House". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (August 20, 2015). "21 First Drafts: Philip Johnson's 9 Ash Street House". Curbed. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Harvard University Town Gown Report (PDF) (Report). Harvard Planning Office. 2016. p. 15. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c Wortman, Marc (2016). 1941: Fighting the Shadow War: A Divided America in a World at War (First ed.). New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-2511-8. OCLC 922911666.

- ^ "PHILIP JOHNSON". IDS Center. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ "At Camp Humphreys, Va". The Sunday Star, Washington, DC, pg 68. June 23, 1918. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/332637670

- ^ Friedman, Alice T., Women and the Making of the Modern House, p 130, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press (2006), ISBN 978-0-300-11789-9, retrieved via Google Books on August 8, 2010

- ^ Taschen 2016, p. 317.

- ^ "Four Seasons & Brasserie Restaurants, Seagram Building, NYC". NYIT Architectural History. YouTube. May 4, 2012. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "AD Classics: Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute / Philip Johnson". ArchDaily. April 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Asad Syrkett, http://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/5335-a-golden-anniversary-for-a-philip-johnson-museum

- ^ Taschen 2016, pp. 315–317.

- ^ "Fort Worth Water Gardens”, on Site of the City of Fort Worth.

- ^ Rojas, Rick (November 26, 2013). "Catholic Renovation of Crystal Cathedral to Begin". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ [1] Architectural Daily - Great Buildings

- ^ "Garden Grove Church". GreatBuildings.com. 1979. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Taschen 2016, pp. 314–317.

- ^ Lorentz, Wayne. "The Bank of America Center-Houston Architecture". HoustonArchitecture.com. Draloc LLC. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Kleber, John E. (2001). The Encyclopedia of Louisville. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0-8131-2100-0.

- ^ [2]"Structurae.com, "Peachtree Tower"

- ^ [3]"Get to Know Philip Johnson's Iconic Architecture", The "Architectural Digest", May 12, 2016

- ^ "Music Academy is Architect's Finale". Los Angeles Times. May 20, 2006. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ "USA Architects to Design Renovations to the Pennsylvania Academy of Music Building". Usaarcitects.com. May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ George Haggerty, ed. (2000). Gay Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Taylor & Francis. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-8153-1880-4.

- ^ Schulze, Franz (1996). Philip Johnson: Life and Work. University of Chicago Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-226-74058-4. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Pierce, Lisa, "Through the Looking Glass", August 1, 2010, pp 1, A4, The Advocate of Stamford, Connecticut

- ^ Gutoff, Bija, "Philip Johnson: A Glass House Opens" Archived February 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, at Apple website, no date given, retrieved August 8, 2010

- ^ Kennedy, Randy (June 14, 2005). "David Whitney, 66, Renowned Art Collector, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ Bourdon, David (May 1970). "What's Up in Art, The Castelli Clan". Life. Accessed June 9, 2010.

- ^ Glass House history chapter 1 Archived October 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frederic Church's Olana on the Hudson. Hudson, NY: The Olana Partnership/Rizzoli International Publications. 2018. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8478-6311-2.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (May 30, 1999). "Artists in Residence; Architecture: A half-dozen houses in New York and Massachusetts paint revealing pictures of their famous inhabitants' talents and times". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Lamster, Mark (October 31, 2018). "Was Architect Philip Johnson a Nazi Spy? (book excerpt)". New York Magazine Intelligencer. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Wortman, Marc (2016). 1941: Fighting the Shadow War: A Divided America in a World at War. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-1-5318-6502-3. OCLC 963235305.. Quoted in Wortman, Marc (April 4, 2016). "Famed Architect Philip Johnson's Hidden Nazi Past". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Shirer, William L. (October 23, 2011). Berlin Diary. Rosetta Books. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7953-1698-2. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Hurowitz, Richard (September 26, 2016). "Don't forget Philip Johnson's Nazi past". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Saval, Nikil (December 12, 2018). "Philip Johnson, the Man Who Made Architecture Amoral". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "Philip Johnson FBI file, part 1. pg 84". Internet Archive. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Wortman, Marc (April 4, 2016). "Famed Architect Philip Johnson's Hidden Nazi Past". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ Stern, Robert A. M. (May 2005). "Philip Johnson: An Essay by Robert A.M. Stern". Architectural Record. Archived from the original on May 7, 2005. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c Interview with Charlie Rose (July 8, 1996)

- ^ "Letter". Google Docs. January 18, 2021 [2020-11-27]. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Bahr, Sarah (December 3, 2020). "Artists Ask MoMA to Remove Philip Johnson's Name, Citing Racist Views". New York Times.

- ^ Cohen, Noam (March 26, 2021). "Sure, erase the names of history's racists. That won't undo their messes". Washington Post.

- ^ Curkin, Charles (December 2, 2020). "Architect Balkrishna Doshi on the need for a reckoning in design". Elle Decor. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Hickman, Matt (December 8, 2020). "Harvard will remove Philip Johnson's name from Cambridge home that he designed as graduate student". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Philip Johnson (February 1999). "Philip Johnson: What I've Learned". Esquire (Interview). Interviewed by John H. Richardson. Retrieved May 15, 2018.(subscription required)

- ^ Johnson, Philip (1955). "The Seven Crutches of Modern Architecture". Perspecta. 3: 40–45. doi:10.2307/1566834. JSTOR 1566834. alternate URL

- ^ Fixsen, Anna (January 18, 2016). "Richard Rogers "Delighted" to Have Been Name-Dropped in David Bowie Song". Architectural Record. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ "Film and Architecture 'My Architect'". June 4, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

Bibliography

- Schulze, Franz (1996). Philip Johnson: Life and Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-74058-4. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Bony, Anne (2012). L'Architecture Moderne (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-587641-6.

- Taschen, Aurelia; Taschen, Balthazar (2016). L'Architecture Moderne de A à Z (in French). Bibliotheca Universalis. ISBN 978-3-8365-5630-9.

- Prina, Francesca; Demaratini, Demartini (2006). Petite encyclopédie de l'architecture (in French). Solar. ISBN 2-263-04096-X.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Les styles en architecture- guide visuel (in French). Dunod. ISBN 978-2-10-070689-1.

- De Bure, Gilles (2015). Architecture contemporaine- le guide (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-134385-6.

- Lamster, Mark (2018). The Man in the Glass House: Philip Johnson, Architect of the Modern Century. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-12643-4.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. London: Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

Further reading

- Lacayo, Richard (June 28, 2007). Splendor in The Glass. Time. Retrieved March 2021.

- Philip Johnson: Diary of an Eccentric Architect, 1997 documentary. Retrieved March 2021

- "Extending the Legacy" Alexandra Lange article on the preservation of the Glass House, from the November 2006 issue of Metropolis magazine.

- Philip Johnson article at Great Buildings Online. Retrieved September 27, 2003.

- Philip Johnson bio on the Pritzker Architecture Prize website. Retrieved September 27, 2003.

- Philip Johnson and Charlie Rose. Retrieved March 2021.

- Heyer, Paul, ed. (1966). Architects on Architecture: New Directions in America, p. 279. New York: Walker and Company.

- One hour interview with Charlie Rose (July 8, 1996) Retrieved March 2021

- Other interviews with or about Philip Johnson on Charlie Rose at Google Video Retrieved March 2021

- Tomkins, Calvin (May 15, 1977). "Forms Under Light" (Profile of Philip Johnson).The New Yorker.

- Jenkins, Stover, et al. The Houses of Philip Johnson, New York: Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.), 2001.

External links

- Obituary Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Philip Johnson architectural drawings, 1943-1994 (bulk 1943-1970).Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- The Architecture of Philip Johnson

- "Philip Johnson Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- Finding aid for Philip Johnson architectural projects at the Getty Research Institute

- Finding aid for Philip Johnson papers at the Getty Research Institute

- Philip Johnson at IMDb

- 1906 births

- 2005 deaths

- AIGA medalists

- 20th-century American architects

- Harvard Graduate School of Design alumni

- LGBT people from Ohio

- LGBT architects

- Modernist architects from the United States

- People from New Canaan, Connecticut

- Architects from Cleveland

- Architects from New York City

- Postmodern architects

- Pritzker Architecture Prize winners

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- People associated with the Museum of Modern Art (New York City)

- People from New London, Ohio

- Architects of the Boston Public Library

- Hackley School alumni

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- Recipients of the AIA Gold Medal

- American fascists

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Ritchie Boys

- American people of Dutch descent

![Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York (1960)[30]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/eb/Munson-Williams-Proctor_Arts_Institute%2C_Utica_NY.jpg/405px-Munson-Williams-Proctor_Arts_Institute%2C_Utica_NY.jpg)