China National Highway 219

| National Highway 219 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 219国道 | ||||

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Length | 10,000 km (6,200 mi) 2,342 km (1,455 mi) until 2013. Proposed length is over 10,000 km (6,214 mi), according to a 2013–2030 government plan | |||

| Existed | 1955–present | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| north-west end | Kom-Kanas Mongolian Ethnic Township | |||

| south-east end | Dongxing | |||

| Location | ||||

| Country | China | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

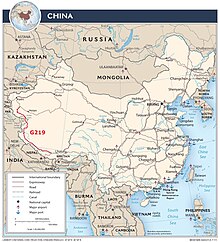

China National Highway 219 (G219; Chinese: Guódào219) is a highway which runs along the entire western and southern border of the People's Republic of China, from Kom-Kanas Mongolian ethnic township in Xinjiang to Dongxing in Guangxi. At over 10,000 kilometres (6,214 mi) long, it is part of the China National Highway Network Planning (2013–2030), and once completed it will be the longest National Highway.

Before 2013, G219 ran from Yecheng (Karghilik) in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to Lhatse in the Tibet Autonomous Region. It was 2,342 km (1,455 mi) long. This section was completed in September 1957. India disagrees with China over its 180 km (112 mi) territorial footprint in Aksai Chin. During the 1962 war, China defended the road, also pushing its western frontier further west. For the first time after the 1960s, between 2010-2012, China spent CN¥3 Billion ($476 million) repaving the Xinjiang section spanning just over 650 km (404 mi). China's 13th (2016–2020) and 14th (2021–2025) five-year plans both included development of the road and connectivity with other roads.

Former G219

Construction of this road as a gravel road was started in 1951.[1] It is also known as the 'Yehchang–Gartok road', the 'Aksai Chin road',[2] and the 'Sky Road'.[3] About 180 km (112 mi) passes through Aksai Chin.[4]

Xinjiang-Tibet road, Aksai Chin

This section contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (July 2022) |

Through 1950s China planned and constructed a road through its western frontier in Xinjiang and Tibet (Hotan/Rutog).[5][clarification needed] China announced completion of the road in September 1957.[6][7] A number of reasons[weasel words] for building the road has been conceptualized, including cementing China's control over the region.[5][clarification needed] India supposedly[weasel words] learnt of the construction a couple of years[weasel words] after the road construction started.[5] Despite the historic remoteness of the region,[clarification needed] both sides lay claim to the area.[5]

The road entered disputed territory "just east of Sarigh Jilgnang" after which it ran through a number of locations[clarification needed] India recognized as its territory such as Haji Langar, and usage was claimed by India to be in contravention to the Sino-Indian Agreement 1954.[8] The following years saw China repave the road which resulted in localized tension.[5][clarification needed] One of the reasons for the 1962 war was the defence of that road.[9][3][according to whom?] In the defence of the road, China pushed its western frontier further west.[10][according to whom?]

Dispute over the territory persists to the present time.[5] There is a Chinese war memorial on the G219 at Kangxiwar.[11] A number of lateral roads have been constructed with scattered military infrastructure.[11][clarification needed]

Road development

Repaving of the road began in late 2010.[12] By July 2012 and with an expenditure of CN¥3 Billion ($476 million), the Xinjiang section spanning just over 650 km (404 mi) was completed.[12] This was the first repaving since the 1960s, according to a Chinese road administration official.[12] The 13th five-year plan of China (2016–2020) further upgraded the road.[13] In 2013 the road was upgraded to asphalt.[4] A number of provincial roads have been and are being developed which exit off from the G219, the G564 and the G365,[14] and the S205, S206, S207.[15] China 14th five-year plan for 2021–2025 further improves connectivity with G219.[16]

Route description

As one of the highest motorable roads in the world, the breathtaking scenery of Rutog County also ranks as some of the most inhospitable terrain on the planet. Domar township—a town of concrete blocks and nomad tents—is one of the bleakest and most remote outposts of the People's Liberation Army at the edge of the Aksai Chin. Near the town of Mazar many trekkers turn off for both the Karakorum range and K2 base camp. Approaching the Xinjiang border, past the final Tibetan settlement of Tserang Daban is a dangerous 5,050-meter-high pass. Tibetan nomads in the area herd both yaks and two-humped camels. Descending through the western Kunlun Shan, the road crosses additional passes of 4,000 and 3,000 meters, and the final pass offers brilliant views of the Taklamakan Desert far below before descending into the Karakax River basin.

The Chinese government is making efforts to promote tourism along G219.[17][18] There are a number of military check posts along the road.[19]

Route and distance

Mountain Passes Rhyme

The western portion of the highway has numerous notable mountain passes. Motorists have invented a rhyme describing those mountain passes:[20][21]

(optional preamble) |

(optional preamble) |

Gallery

-

G219 in Barga Township, Tibet

-

G219 in Burang, Tibet

-

Few kilometers south of the border between Xinjiang and Tibet on the G219.

-

Same mountains as previous image but closer

-

Heiqiazi Daban (Kirgizjangal Pass) in Kargilik County, Xinjiang

-

Mazar Pass (Chiragsaldi Pass) in Kargilik County, Xinjiang

New route

The route was expanded in the China National Highway Network Planning (2013–2030) both northward and eastward to span the entire Chinese western and southern border. The new route will measure over 10,000 km (6,214 mi), making it by far the longest National Highway.

The section along the China-Vietnam border is also known as the Yanbian Highway (沿边公路, literally: along the border highway).[22][unreliable source?][23]

Route table

See also

- China National Highways

- China National Highway 228, which follows the coastline of China

- China National Highway 331, which follows the northern border of China

References

- ^ "MemCons of Final sessions with the Chinese" (PDF). The White House. 12 August 1971. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2011 – via National Security Archive's legacy site.

Memorandum for: Henry A. Kissinger. From: Winston Lord.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Arpi, Claude (27 October 2021). "Dark clouds over Himalayas: Analysing China's new Land Border Law and why India needs to be more aggressive". Firstpost. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ a b Babones, Salvatore (13 July 2020). "China's Incursions into India Are Really All about Tibet". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

When China and India did go to war in 1962, it was over a road. China began construction of National Highway G219, the Sky Road ...

- ^ a b Duhalde, Marcelo; Wong, Dennis; Lee, Kaliz. "Why did an India-China border clash turn into a deadly scuffle?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Taillard, Michael (2018). Economics and Modern Warfare: The Invisible Fist of the Market. Springer. pp. 267–268. ISBN 978-3-319-92693-3.

- ^ Sinha, Rakesh (18 August 2019). "History Headline: Aksai Chin, from Nehru to Shah". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "50th anniversary of Xinjiang-Tibet Highway marked". The Government of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. China Tibet Information Center. 1 November 2007. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ministry of External Affairs, India (ed.). Notes, Memoranda and letters Exchanged and Agreements signed between The Governments of India and China 1954 –1959. Government of India Press.

- ^ Wu, Jin; Myers, Steven Lee (18 July 2020). "Battle in the Himalayas". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Raj, Prakash (10 September 2020). "Why Did China Ramp up Massive Infrastructure Along the LAC?". The Geopolitics. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ a b Bhat, Col Vinayak (29 August 2021). "China constructs new road links to Ladakh on stretch that sparked 1962 war". India Today. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Krishnan, Ananth (11 July 2012). "China spruces up highway through Aksai Chin". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Desai, Suyash (November 2021). "Infrastructure Development in Tibet and its Implications for India". Jamestown Foundation's China Brief (Volume 21 Issue 22). Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021 – via Takshashila Institution.

- ^ Arpi, Claude (26 January 2017). "Smell the coffee along the China border". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "S207 Provincial Route". www.dangerousroads.org. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Krishnan, Ananth (11 March 2021). "China's new Five-Year Plan outlines push for key strategic projects". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Tibet makes strong tourism recovery". China.org.cn. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Ultimate Guide to Lhasa Kailash Kashgar Overland Tour via Xinjiang Tibet Highway". Tibet Travel Blog. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Master, Farah (29 October 2010). "China Motorcycle Diaries: altitude sickness at 5000m". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ 杨芳秀 (May 2019). "一次震撼心灵的雪山之行" [A trip to the snow-capped mountains that shocked the soul]. The Press (in Chinese). People's Daily. ISSN 0257-5930. Archived from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

常年往来于这条路上的官兵,编了一句顺口溜来形容路上的艰辛:"库地达坂险,犹似鬼门关;麻扎达坂尖,陡升五千三;黑卡达坂旋,九十九道弯;界山达坂弯,喘气真是难。

- ^ 流年. 鬼藏人 [Ghost Tibetan] (in Chinese). 知識屋. p. 1051.

- ^ "自驾西双版纳到瑞丽,我们选择走沿边公路219国道,第一天宿雪林". www.ixigua.com. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ 通讯员 窦海蓉 李岩旺 (21 April 2020). "国道G219线南撒至岗莫标山建设项目稳步推进" [The construction project of National Highway G219 from Nansa to Gangmobiaoshan is progressing steadily]. m.yunnan.cn. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

Further reading

- Dorje, Gyurme. (2009). Footprint Tibet Handbook. (4th Ed.) Footprint Handbooks, Bath, England. ISBN 978-1-906098-32-2.

- "China National Highway 219, one of the highest roads on Earth". www.dangerousroads.org. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- Arpi, Claude (13 January 2021). "The Most Serious Strategic Development on Indian Frontiers". Retrieved 23 December 2021 – via Indian Defence Review.

- Huttenback, R. A. (1964). "A Historical Note on the Sino-Indian Dispute over the Aksai Chin". The China Quarterly. 18 (18): 201–207. doi:10.1017/S0305741000041977. ISSN 0305-7410. JSTOR 3082130. S2CID 155074304.

- Dreams of Snow Land. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. 2005. pp. 279-294. ISBN 7-119-03883-4 – via Internet Archive.

External links

Media related to China National Highway 219 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to China National Highway 219 at Wikimedia Commons Works related to 国家公路网规划(2013年-2030年) at Wikisource

Works related to 国家公路网规划(2013年-2030年) at Wikisource- Xinjiang-Tibet Highway (Yecheng-Burang)

- The Highway 219 from Yecheng over Western Tibet to Kathmandu Archived 9 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Description and profile of the route.

- From Kashgar to Lhassa Photos along highway 219 (text in French).

- Some photos along the Highway 219

- A detailed description of a bicycle ride along highway 219 with many photos

- Photographs of a 2018 trip along G219