Joseph Colombo

Joseph Colombo | |

|---|---|

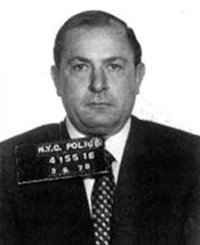

Colombo's March 6, 1970 mugshot | |

| Born | Joseph Anthony Colombo June 16, 1923 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 22, 1978 (aged 54) Newburgh, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. John's Cemetery, Queens |

| Occupation | Crime boss |

| Predecessor | Joseph Magliocco |

| Successor | Carmine Persico |

| Spouse |

Lucille Faiello (m. 1944) |

| Children | 5 |

| Allegiance | Colombo crime family Italian-American Civil Rights League |

| Conviction(s) | Contempt of court (1966) |

| Criminal penalty | 30 days in prison |

Joseph Anthony Colombo Sr. (Italian: [koˈlombo]; June 16, 1923 – May 22, 1978) was the boss of the Colombo crime family, one of the Five Families of the American Mafia in New York City.

Colombo was born in New York City, where his father was an early member of what was then the Profaci crime family. In 1961, the First Colombo War unfolded, instigated by the kidnapping of four high-ranking members in the Profaci family by Joe Gallo. Later that year, Gallo was imprisoned, and in 1962, family leader Joe Profaci died of cancer. In 1963, Bonanno crime family boss, Joseph Bonanno made plans with Joseph Magliocco to assassinate several rivals on The Commission. Magliocco gave the contract to one of his top hit men, Colombo, who revealed the plot to its targets. The Commission spared Magliocco's life but forced him into retirement, while Bonanno fled to Canada. As a reward for turning on his boss, Colombo was awarded the Profaci family. His only prison term would come in 1966, when Colombo was sentenced to 30 days in prison for contempt of court by refusing to answer questions from a grand jury about his financial affairs.

In 1970, Colombo created the Italian-American Civil Rights League. Later that year, the first Italian Unity Day rally was held in Columbus Circle to protest the federal persecution of Italians. In 1971, Gallo was released from prison, and Colombo invited him to a peace meeting with an offering of $1,000, which Gallo refused, instigating the Second Colombo War. On June 28, 1971, Colombo was shot three times by Jerome Johnson at the second Italian Unity Day rally in Columbus Circle sponsored by the Italian-American Civil Rights League; Johnson was immediately killed by Colombo's bodyguards. Colombo was paralyzed from the shooting. On May 22, 1978, Colombo died of cardiac arrest that resulted from his injuries.

Early life

Joseph Colombo Sr. was born into an Italian American family on June 16, 1923, in Brooklyn.[1] His father, Anthony Colombo, was an early member of the Profaci crime family, which would eventually be renamed after his son. In 1938, he was found strangled in a car with his mistress.[2] Joe Colombo attended New Utrecht High School in Brooklyn for two years, then dropped out to join the U.S. Coast Guard. In 1945, he was diagnosed with neurosis and discharged from the service. His legitimate jobs included ten years as a longshoreman and six years as a salesman for a meat company.[1] His final job was that of a real estate salesman.[2]

Colombo owned a modest home in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn and a five-acre estate in Blooming Grove, New York.[1] He married Lucille Faiello in 1944, and had five children including sons Christopher Colombo, Joseph Colombo Jr. (1946–2014)[3] and Anthony Colombo (1945–2017).[4][5]

First Colombo War

Colombo followed his father into the Profaci family. He became one of the family's top enforcers, and soon became a capo.

On February 27, 1961, the Gallos kidnapped four of Profaci's top men: underboss Magliocco, Frank Profaci (Joe Profaci's brother), capo Salvatore Musacchia and soldier John Scimone.[6] Profaci himself eluded capture and flew to sanctuary in Florida.[6] While holding the hostages, Larry and Albert Gallo sent Joe Gallo to California. The Gallos demanded a more favorable financial scheme in return for the hostages' release. Gallo wanted to kill one hostage and demand $100,000 before negotiations, but his brother Larry overruled him. After a few weeks of negotiation, Profaci made a deal with the Gallos.[7] Profaci's consigliere Charles "the Sidge" LoCicero negotiated with the Gallos and all the hostages were released peacefully.[8] However, Profaci had no intention of honoring this peace agreement. On August 20, 1961, Profaci ordered the murder of Gallo family members Joseph "Joe Jelly" Gioielli and Larry Gallo. Gunmen allegedly murdered Gioilli after inviting him to go fishing.[6] Larry Gallo survived a strangulation attempt in the Sahara club of East Flatbush by Carmine Persico and Salvatore "Sally" D'Ambrosio after a police officer intervened.[6][9] The Gallo brothers had been previously aligned with Persico against Profaci and his loyalists;[6][9] The Gallos then began calling Persico "The Snake" after he had betrayed them.[9] The war continued and resulted in nine murders and three disappearances.[9] With the start of the gang war, the Gallo crew retreated to the Dormitory.[10]

In late November 1961, Joe Gallo was sentenced to seven-to-fourteen years in prison for murder.[11] On June 6, 1962, Profaci died and was succeeded by longtime underboss Joseph Magliocco. In 1963, Joseph Bonanno, the head of the Bonanno crime family, made plans to assassinate several rivals on the Mafia Commission—bosses Tommy Lucchese, Carlo Gambino, and Stefano Magaddino, as well as Frank DeSimone.[12] Bonanno sought Magliocco's support, and Magliocco readily agreed. Bonanno was not only bitter from being denied a seat on the Commission, but he and Profaci had been close allies for over 30 years prior to Profaci's death. Bonanno's audacious goal was to take over the Commission and make Magliocco his right-hand man.[13] Magliocco was assigned the task of killing Lucchese and Gambino, and gave the contract to one of his top hit men, Colombo. However, the opportunistic Colombo revealed the plot to its targets. The other bosses quickly realized that Magliocco could not have planned this himself. Remembering how close Bonanno was with Magliocco (and before him, Profaci), as well as their close ties through marriages, the other bosses concluded Bonanno was the real mastermind.[13] The Commission summoned Bonanno and Magliocco to explain themselves. Fearing for his life, Bonanno went into hiding in Montreal, leaving Magliocco to deal with the Commission. Badly shaken and in failing health, Magliocco confessed his role in the plot. The Commission spared Magliocco's life, but forced him to retire as Profaci family boss and pay a $50,000 fine. As a reward for turning on his boss, Colombo was awarded the Profaci family.[13]

At the age of 41, Colombo was one of the youngest crime bosses in the country. He was also the first American-born boss of a New York crime family. When NYPD detective Albert Seedman (later the NYPD chief of detectives) called Colombo in for questioning about the death of one of his soldiers, Colombo came to the meeting without a lawyer. He told Seedman, "I am an American citizen, first class. I don't have a badge that makes me an official good guy like you, but I work just as honest for a living."[14]

On May 9, 1966, Colombo was sentenced to 30 days in jail for contempt by refusing to answer questions from a grand jury about his financial affairs.[15]

Italian-American Civil Rights League

In April 1970, Colombo created the Italian-American Civil Rights League. That same month, his son Joseph Colombo Jr. was charged with melting down coins for resale as silver ingots.[16] In response, Joseph Colombo Sr. claimed FBI harassment of Italian-Americans and, on April 30, 1970, sent 30 picketers outside FBI headquarters at Third Avenue and 69th Street to protest the federal persecution of all Italians everywhere; this went on for weeks.[16] On June 29, 1970, 50,000 people attended the first Italian Unity Day rally in Columbus Circle in New York City.[17][18][19] In February 1971, Colombo Jr. was acquitted of the federal charge after the chief witness in the trial was arrested on perjury charges.[20]

Under Colombo's guidance, the League grew quickly and achieved national attention. Unlike other mob leaders who shunned the spotlight, Colombo appeared on television interviews, fundraisers and speaking engagements for the League. In 1971, Colombo aligned the League with Rabbi and political activist Meir Kahane's Jewish Defense League, claiming that both groups were being harassed by the federal government.[21] At one point, Colombo posted bail for 11 jailed JDL members.[22]

The Godfather

In the spring of 1971, Paramount Pictures started filming The Godfather with the assistance of Colombo and the League. Due to its subject matter, the film originally faced great opposition from Italian-Americans to filming in New York. However, after producer Albert Ruddy met with Colombo and agreed to excise the terms "Mafia" and "Cosa Nostra" from the film, the League cooperated fully.[23] The first meeting involved Ruddy, Colombo, Colombo's son Anthony and 1500 delegates from Colombo's Italian-American Civil Rights League.[24] Ruddy would afterwards hold numerous meetings with Anthony, which led to assurance that the film would be based on individuals and would not defame or stereotype a group.[24]

Shooting

In early 1971, Joe Gallo was released from prison. As a supposedly conciliatory gesture, Colombo invited Gallo to a peace meeting with an offering of $1,000.[25] Gallo refused the invitation, wanting $100,000 to stop the conflict, which Colombo refused to pay.[26] At that point, acting boss Vincenzo Aloi issued a new order to kill Gallo.[26]

On March 11, 1971, after being convicted of perjury for lying on his application to become a real estate broker, Colombo was sentenced to two and half years in state prison.[27] The sentence, however, was delayed pending an appeal.[28]

On June 28, 1971, Colombo was shot three times in the head and neck by Jerome A. Johnson, with one of the bullets hitting him in the head, at the second Italian Unity Day rally in Columbus Circle sponsored by the Italian-American Civil Rights League; Johnson was immediately killed by Colombo's bodyguards.[1]

Aftermath

Colombo was paralyzed from the shooting.[1] On August 28, 1971, after two months at Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, Colombo was moved to his estate at Blooming Grove.[29] In 1975, a court-ordered examination showed that Colombo could move his thumb and forefinger on his right hand. In 1976, there were reports that he could recognize people and utter several words.[1]

After the Colombo shooting, Joseph Yacovelli became the acting boss for one year before Carmine Persico took over.[30]

Although many in the Colombo family blamed Joe Gallo for the shooting, the police eventually concluded that Johnson was a lone gunman after they had questioned Gallo.[31] Since Johnson had spent time a few days earlier at a Gambino club, one theory was that Carlo Gambino organized the shooting. Colombo refused to listen to Gambino's complaints about the League, and allegedly spat in Gambino's face during one argument.[32] However, the Colombo family leadership was convinced that Joe Gallo ordered the murder after his falling out with the family.[33] Gallo was murdered on April 7, 1972.[34]

Death

On May 22, 1978, Colombo died of cardiac arrest at St. Luke's Hospital (later St. Luke's Cornwall Hospital) in Newburgh, New York.[1]

Colombo's funeral was held at St Bernadette's Catholic Church in Bensonhurst and he was buried in Saint John Cemetery in the Middle Village section of Queens.[35]

In popular culture

- Colombo features in the first episode of UK history TV channel Yesterday's documentary series Mafia's Greatest Hits[36]

- In "Christopher", an episode of The Sopranos, Silvio Dante claims that Colombo was the founder of the first Italian-American anti-defamation organization. However, the American Italian Anti-Defamation League was founded before Colombo's Italian-American Civil Rights League

- In 2015, Joe Colombo's oldest son, Anthony Colombo, authored Colombo: The Unsolved Murder[37] a biography/memoir with co-author Don Capria

- The 2019 Martin Scorsese film The Irishman depicts the assassination attempt on Colombo, who is played by John Polce.

- Colombo is played by Giovanni Ribisi in the 2022 Paramount+ limited streaming series The Offer, which details the making of the film The Godfather.

- Colombo is portrayed by Michael Raymond-James in the third season of the television series Godfather of Harlem, which premiered in 2023

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Joseph A. Colombo, Sr,. Paralyzed in Shooting at 1971 Rally, Dies". New York Times. May 24, 1978.

- ^ a b Gage, Nicholas (May 3, 1971). "Colombo: The New Look in the Mafia" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ "Brooks Funeral Home : Newburgh, New York (NY)". Brooks Funeral Home. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "Anthony Colombo, 71; helped get 'Mafia' out of 'The Godfather'". Boston Globe. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Anthony Colombo Dies at 71; Helped Get 'Mafia' Out of 'The Godfather'". The New York Times. January 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Cage, Nicholas (July 17, 1972) "Part II The Mafia at War" New York pp.27-36

- ^ Sifakis, Carl (2005). The Mafia encyclopedia (3. ed.). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-5694-3.

- ^ Capeci (2001), p.303

- ^ a b c d Raab (2006), pp.321-324

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (October 23, 1966). "Robin Hoods or Real Tough Boys:Larry Gallo, Crazy Joe, and Kid Blast" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Capeci (2001) p.305

- ^ Staff (September 1, 1967) "The Mob: How Joe Bonanno Schemed to kill – and lost" Life p.15-21

- ^ a b c Bruno, Anthony. "Colombo Crime Family: Trouble and More Trouble". TruTV Crime Library. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn. The Five Families: The Rise, Decline & Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empire. New York: St. Martins Press, 2005. p. 187

- ^ "Mafia Figure Gets a Contempt Term" (PDF). New York Times. May 10, 1966. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ a b "Small-time mob boss Joe Colombo's great civil rights crusade". New York Daily News. August 14, 2017.

- ^ "Thousands of Italians Here Rally Against Ethnic Slurs". The New York Times. June 30, 1970.

- ^ "Italo-Americans Press Unity Day" (PDF). New York Times. June 18, 1970. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Vincenza Scarpaci (2008). The Journey of the Italians in America. Pelican. ISBN 9781455606832.

- ^ "Colombo Acquitted In Conspiracy Case". The New York Times. February 27, 1971.

- ^ Kaplan, Morris (May 14, 1971). "Kahane and Colombo Join Forces to Fight Reported U.S. Harassment" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Rosenthal, Richard (2000). Rookie cop : deep undercover in the Jewish Defense League. Wellfleet, Mass.: Leapfrog Press. ISBN 0-9654578-8-5.

- ^ Pileggi, Nicholas (August 15, 1971). "The Making of 'The Godfather: Sort of a Home Movie". New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Pileggi, Nicholas (August 15, 1971). "The Making of "The Godfather"—Sort of a Home Movie". The New York Times Magazine. The Stacks Reader. ISSN 0028-7822. Archived from the original (Archive) on December 11, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Fosburgh, Lacy (June 12, 1973). "Mafia Informer Says Aloi Ordered Gallo Killing" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Gage, Nicholas (July 5, 1971). "Colombo's Refusal to Buy Off Gallo for $100,000 Cited" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (March 23, 1971). "Corporate Rift in 'Godfather' Filming". New York Times.

- ^ Bruno, Anthony. "TruTV Crime Library". The Colombo Family: The Olive Oil King. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Weisman, Steven R. (August 28, 1971). "Colombo Leaves the Hospital Two Months After the Shooting" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Gage, Nicholas (September 1, 1971). "Yacovelli Said to Succeed Colombo in Mafia Family" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Gage, Nicholas (April 8, 1972). "Grudges with Gallo Date to War with Profaci" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (July 20, 1971). "Suspect in Shooting of Colombo Linked to Gambino Family". New York Times.

- ^ Abadinsky, Howard (2010). Organized crime (9th ed.). Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-495-59966-1.

- ^ Gage, Nicholas (May 3, 1972). "Story of Joe Gallo's Murder" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Gupte, Pranay (May 27, 1978). "Colombo is Eulogized as a Champion of Civil Rights" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Mafia's Greatest Hits.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (January 24, 2017). "Anthony Colombo Dies at 71; Helped Get 'Mafia' Out of 'The Godfather'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

Further reading

- Capria, Don and Anthony Colombo. Colombo: The Unsolved Murder. New York: Unity Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0692583241

- Reppetto, Thomas. Bringing Down the Mob. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006. ISBN 0-8050-7802-9

- Moore, Robin and Barbara Fuca. Mafia Wife. New York: MacMillan, 1977, ISBN 0-02-586180-8

- 1923 births

- 1978 deaths

- 20th-century American criminals

- American civil rights activists

- American male criminals

- American shooting survivors

- American Zionists

- Bosses of the Colombo crime family

- Burials at St. John's Cemetery (Queens)

- Criminals from Brooklyn

- Deaths from cardiac arrest

- New Utrecht High School alumni

- People from Blooming Grove, New York

- People from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn