History of nudity

The history of nudity involves social attitudes to nakedness of the human body in different cultures in history. The use of clothing to cover the body is one of the changes that mark the end of the Neolithic, and the beginning of civilizations. Nudity (or near-complete nudity) has traditionally been the social norm for both men and women in hunter-gatherer cultures in warm climates, and it is still common among many indigenous peoples. The need to cover the body is associated with human migration out of the tropics into climates where clothes were needed as protection from sun, heat, and dust in the Middle East; or from cold and rain in Europe and Asia. The first use of animal skins and cloth may have been as adornment, along with body modification, body painting, and jewelry, invented first for other purposes, such as magic, decoration, cult, or prestige. The skills used in their making were later found to be practical as well.

In modern societies, complete nudity in public became increasingly rare as nakedness became associated with lower status, but the mild Mediterranean climate allowed for a minimum of clothing, and in a number of ancient cultures, the athletic and/or cultist nudity of men and boys was a natural concept. In ancient Greece, nudity became associated with the perfection of the gods. In ancient Rome, complete nudity could be a public disgrace, though it could be seen at the public baths or in erotic art. In the Western world, with the spread of Christianity, any positive associations with nudity were replaced with concepts of sin and shame. Although rediscovery of Greek ideals in the Renaissance restored the nude to symbolic meaning in art, by the Victorian era, public nakedness was considered obscene. In Asia, public nudity has been viewed as a violation of social propriety rather than sin; embarrassing rather than shameful. However, in Japan, mixed-gender communal bathing was quite normal and commonplace until the Meiji Restoration.

While the upper classes had turned clothing into fashion, those who could not afford otherwise continued to swim or bathe openly in natural bodies of water or frequent communal baths through the 19th century. Acceptance of public nudity re-emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Philosophically based movements, particularly in Germany, opposed the rise of industrialization. Freikörperkultur ('free body culture') represented a return to nature and the elimination of shame. In the 1960s naturism moved from being a small subculture to part of a general rejection of restrictions on the body. Women reasserted the right to uncover their breasts in public, which had been the norm until the 17th century. The trend continued in much of Europe, with the establishment of many clothing-optional areas in parks and on beaches.

Through all of the historical changes in the developed countries, cultures in the tropical climates of sub-Saharan Africa and the Amazon rainforest have continued with their traditional practices, being partially or completely nude during everyday activities.

Prehistory

Evolution of hairlessness

The relative hairlessness of homo sapiens requires a biological explanation, given that fur evolved to protect other primates from UV radiation, injury, sores and insect bites. Many explanations include advantages to cooling when early humans moved from shady forest to open savanna, accompanied by a change in diet from primarily vegetarian to hunting game, which meant running long distances after prey.[1] Another explanation is that fur harbors ectoparasites such as ticks, which would have become more of a problem as humans became hunters living in larger groups with a "home base".[2] However, that would be inconsistent with the abundance of parasites that continue to exist in the remaining patches of human hair.[3]

Jablonski and Chaplin assert that early hominids, like modern chimpanzees, had light skin covered with dark fur. With the loss of fur, high melanin skin soon evolved as protection from damage from UV radiation. As hominids migrated outside of the tropics, varying degrees of depigmentation evolved in order to permit UVB-induced synthesis of previtamin D3.[4]

The loss of body hair was a factor in several aspects of human evolution. The ability to dissipate excess body heat through eccrine sweating helped to make possible the dramatic enlargement of the brain, the most temperature-sensitive organ. Nakedness and intelligence also made it necessary to evolve non-verbal signaling mechanisms, such as blushing and facial expressions. Signalling was supplemented by the invention of body decorations, which also served the social function of identifying group membership.[5]

Origin of clothing

The wearing of clothing is assumed to be a behavioral adaptation, arising from the need for protection from the elements; including the sun (for depigmented human populations) and cold temperatures as humans migrated to colder regions. It is estimated that anatomically modern humans evolved 260,000 to 350,000 years ago.[6] A genetic analysis estimates that clothing lice diverged from head louse ancestors at least by 83,000 and possibly as early as 170,000 years ago, suggesting that the use of clothing likely originated with anatomically modern humans in Africa prior to their migration to colder climates.[7] What is now called clothing may have originated along with other types of adornment, including jewelry, body paint, tattoos, and other body modifications, "dressing" the naked body without concealing it.[8] Body adornment is one of the changes that occurred in the late Paleolithic (40,000 to 60,000 years ago) that indicate that humans had become not only anatomically but culturally and psychologically modern, capable of self-reflection and symbolic interaction.[9]

One of the indications of self-awareness was the appearance of art. The earliest surviving depictions of the human body include the small figurines found across Eurasia generally termed "Venuses" although a few are male and others are not identifiable. While the most famous are obese, others are slender but indicate pregnancy, which is generalized as representing fertility.[10]

Ancient history

The widespread habitual use of clothing is one of the changes that mark the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of civilization. Clothing and adornment became part of the symbolic communication that marked a person's membership in their society. Thus nakedness in everyday life meant being at the bottom of the social scale, lacking in dignity and status. However, removing clothes while engaged in work or bathing was commonplace, and deities and heroes might be depicted nude to represent fertility, strength, or purity. Some images were subtly or explicitly erotic, depicting suggestive poses or sexual activity.[11]

Mesopotamia

-

Statuette of a naked bearded man (possibly priest-king), Uruk Period, c. 3300 BCE

-

The Burney Relief, First Babylonian Empire (c. 1800 BCE)

In Mesopotamia, most people owned a single item of clothing, usually a linen cloth that was wrapped and tied. Possessing no clothes meant being at the bottom of the social scale, being indebted, or if a slave, not being provided with clothes.[12] In the Uruk period there was recognition of the need for functional and practical nudity while performing many tasks, although the nakedness of workers emphasized the social difference between servants and the elite, who were clothed.[13]

Sculpture representations of nudity indicates positive associations, in particular the fertility of women with large breasts and wide hips. The assumption of sexual shame regarding nudity may be based upon later interpretations. Male nudity represented defeat in battle and death.[14][15] The identity of the goddess depicted in the Burney Relief is a topic of scholarly debate, Lilith, Ishtar/Inanna or Kilili her messenger, and Ereshkigal being proposed.[16]

Egypt

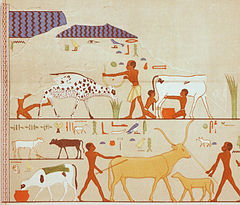

For the average person in ancient Egypt clothing changed little from its beginnings until the Middle Kingdom. Both men and women of the lower classes were commonly bare chested and barefoot, wearing a simple loincloth or skirt around their waist. Slaves might not be provided with clothing.[17] Servants were nude or wore loincloths.[18] Although the genitals of adults were generally covered, nakedness in ancient Egypt was not a violation of any social norm, but more often a convention indicating lack of wealth; those that could afford to do so covered more.[19] Nudity was considered a natural state.[20] Laborers would be naked while performing many tasks, particularly if hot, dirty, or wet; farmers, fishermen, herders, and those working close to fires or ovens.[21][22]

During the Early Dynastic Period, (3150–2686 BCE), and the Old Kingdom, (2686–2180 BCE) the majority of men and women wore similar attire. Skirts called shendyt—which evolved from loincloths and resembled kilts—were customary apparel. Women of the upper classes commonly wore a kalasiris (καλάσιρις), a dress of loose draped or translucent linen which came to just above or below the breasts.[21] Female servants and entertainers at banquets were partly clothed or naked.[22] Children might go without clothing until puberty, at about age 12.[18] The status of upper class children was shown by wearing jewelry, not clothing. Being born naked, humans were also nude in the afterlife (although in new bodies at the prime of life).[22]

In the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BCE) and the Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BCE) clothing for most people remained the same, but fashion for the upper classes became more elaborate.[21] During the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BCE) portions of Egypt were controlled by Nubians and by the Hyksos, a Semitic people. During the brief New Kingdom (1550–1069 BCE), Egyptians regained control. Upper-class women wore elaborate dresses and ornamentation which covered their breasts. Those serving in the households of the wealthy also began wearing more refined dress. These later styles are often shown in film and TV as representing ancient Egypt in all periods.[21]

Aegean civilization

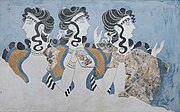

In some ancient Mediterranean cultures, even well past the hunter-gatherer stage, athletic and/or cultist nudity of men and boys – and rarely, of women and girls – was a natural concept. The Minoan civilization prized athleticism, with bull-leaping being a favourite event. Both men and women participated wearing only a loincloth. Everyday dress for men was normally bare-chested, whilst women wore an open-fronted dress.[23][24]

Greece

-

Example of the Cnidian Aphrodite type

-

Myron's 5th century Discobolos, in the British Museum

Male nudity was celebrated in ancient Greece to a greater degree than any culture before or since.[25][26] Hesiod, the writer of the poem Theogony, which describes the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods in Ancient Greek religion, suggested that farmers should "Sow naked, and plough naked, and harvest naked, if you wish to bring in all Demeter's fruits in due season."[27] The status of freedom, maleness, privilege, and physical virtues were asserted by discarding everyday clothing for athletic nudity.[28] Nudity became a ritual costume by association of the naked body with the beauty and power of the gods.[29] The female nude emerged as a subject for art in the 5th century BCE, illustrating stories of women bathing both indoors and outdoors.[30] The passive images reflected the unequal status of women in society compared to the athletic and heroic images of naked men.[31] In Sparta during the Classical period, women were also trained in athletics. Scholars do not agree whether they also competed in the nude, the same word (gymnosis, γύμνωσις: naked or lightly clothed) was used to describe the practice. Women may have competed in specific events, such as foot racing or wrestling, which was consistent with the need to develop endurance.[32] It is otherwise agreed that Spartan women in the classical period were nude only for specific religious and ceremonial purposes.[33] In the Hellenistic period Spartan women trained with men, and participated in more athletic events.[34] However, unlike the later Roman baths, those in Hellenistic Greece were segregated by sex.[35]

Ancient Greece had a particular fascination for aesthetics, which was also reflected in clothing or its absence. Sparta had rigorous codes of training (agoge, ἀγωγή) and physical exercise was conducted in the nude. Athletes competed naked in public sporting events.[36] Spartan women, as well as men, would sometimes be naked in public processions and festivals. This practice was designed to encourage virtue in men while they were away at war and an appreciation of health in the women.[37] Women and goddesses were normally portrayed clothed in sculpture of the Classical period, with the exception of the nude Aphrodite.

In general, however, concepts of either shame or offense, or the social comfort of the individual, seem to have been deterrents of public nudity in the rest of Greece and the ancient world in the east and west, with exceptions in what is now South America, and in Africa and Australia. Polybius asserts that Celts typically fought naked, "The appearance of these naked warriors was a terrifying spectacle, for they were all men of splendid physique and in the prime of life."[38]

In Greek culture, depictions of erotic nudity were considered normal. The Greeks were conscious of the exceptional nature of their nudity, noting that "generally in countries which are subject to the barbarians, the custom is held to be dishonourable; lovers of youths share the evil repute in which philosophy and naked sports are held, because they are inimical to tyranny;"[39]

The origins of nudity in ancient Greek sport are the subject of a legend about the athlete Orsippus of Megara.[40]

Rome

The Greek traditions were not maintained in the later Etruscan and Roman athletics because its public nudity became associated with homoeroticism. Early Roman masculinity involved prudishness and paranoia about effeminacy.[41] The toga was essential to announce the status and rank of male citizens of the Roman Republic (509–27 BCE).[42] The poet Ennius declared, "exposing naked bodies among citizens is the beginning of public disgrace". Cicero endorsed Ennius' words.[43] In the Roman Empire (27 BCE – 476 CE), the status of the upper classes was such that public nudity was of no concern for men, and for women only if seen by their social superiors.[44] At the public Roman baths (thermae), which had social functions similar to a modern beach, mixed nude bathing may have been the norm up to the fourth century CE.[45][46] Jews during the Greco-Roman period maintained negative attitudes towards nudity, both as a temptation for illicit sexuality and a distraction from the life of holiness.[47]

Ancient Roman attitudes toward male nudity differed from those of the Greeks, whose ideal of masculine excellence was expressed by the nude male body in art and in such real-life venues as athletic contests. The toga, by contrast, distinguished the body of the adult male citizen of Rome.[42] The poet Ennius (c. 239–169 BC) declared that "exposing naked bodies among citizens is the beginning of public disgrace (flagitium),[a]" a sentiment echoed by Cicero.[48][49][50][51]

Public nudity might be offensive or distasteful even in traditional settings; Cicero derides Mark Antony as undignified for appearing near-naked as a participant in the Lupercalia festival, even though it was ritually required.[52] Negative connotations of nudity included defeat in war, since captives were stripped and sold into slavery. Slaves for sale were often displayed naked to allow buyers to inspect them for defects, and to symbolize that they lacked the right to control their own bodies.[53] The disapproval of nudity was less a matter of trying to suppress inappropriate sexual desire than of dignifying and marking the citizen's body.[54] Thus the retiarius, a type of gladiator who fought with face and flesh exposed, was thought to be unmanly.[55][56] The influence of Greek art, however, led to "heroic" nude portrayals of Roman men and gods, a practice that began in the 2nd century BC. When statues of Roman generals nude in the manner of Hellenistic kings first began to be displayed, they were shocking—not simply because they exposed the male figure, but because they evoked concepts of royalty and divinity that were contrary to Republican ideals of citizenship as embodied by the toga.[57][58] In art produced under Augustus Caesar, the adoption of Hellenistic and Neo-Attic style led to more complex signification of the male body shown nude, partially nude, or costumed in a muscle cuirass.[59] Romans who competed in the Olympic Games presumably followed the Greek custom of nudity, but athletic nudity at Rome has been dated variously, possibly as early as the introduction of Greek-style games in the 2nd century BC but perhaps not regularly until the time of Nero around 60 AD.[citation needed]

-

Roman Neo-Attic stele depicting a warrior in a muscle cuirass, idealizing the male form without nudity

-

Bare-breasted goddesses on the Augustan Altar of Peace

-

Woman wearing a strophium during sex (Casa del Centenario, Pompeii)

At the same time, the phallus was depicted ubiquitously. The phallic amulet known as the fascinum (from which the English word "fascinate" ultimately derives) was supposed to have powers to ward off the evil eye and other malevolent supernatural forces. It appears frequently in the archaeological remains of Pompeii in the form of tintinnabula (wind chimes) and other objects such as lamps.[60] The phallus is also the defining characteristic of the imported Greek god Priapus, whose statue was used as a "scarecrow" in gardens. A penis depicted as erect and very large was laughter-provoking, grotesque, or apotropaic.[61][62] Roman art regularly features nudity in mythological scenes, and sexually explicit art appeared on ordinary objects such as serving vessels, lamps, and mirrors, as well as among the art collections of wealthy homes.

Respectable Roman women were portrayed clothed. Partial nudity of goddesses in Roman Imperial art, however, can highlight the breasts as dignified but pleasurable images of nurturing, abundance, and peacefulness.[63][64] The completely nude female body as portrayed in sculpture was thought to embody a universal concept of Venus, whose counterpart Aphrodite is the goddess most often depicted as a nude in Greek art.[65][66] By the 1st century AD, Roman art showed a broad interest in the female nude engaged in varied activities, including sex.

The erotic art found in Pompeii and Herculaneum may depict women performing sex acts either naked or often wearing a strophium (strapless bra) that covers the breasts even when otherwise nude.[67] Latin literature describes prostitutes displaying themselves naked at the entrance to their brothel cubicles, or wearing see-through silk garments.[53]

The display of the female body made it vulnerable; Varro thought the Latin word for 'sight, gaze', visus, was etymologically related to vis, 'force, power'. The connection between visus and vis, he said, also implied the potential for violation, just as Actaeon gazing on the naked Diana violated the goddess.[b][c][69]

One exception to public nudity was the thermae (public baths), though attitudes toward nude bathing also changed over time. In the 2nd century BC, Cato preferred not to bathe in the presence of his son, and Plutarch implies that for Romans of these earlier times it was considered shameful for mature men to expose their bodies to younger males.[70][71][54] Later, however, men and women might even bathe together.[72] Some Hellenized or Romanized Jews resorted to epispasm, a surgical procedure to restore the foreskin "for the sake of decorum".[d][e] In Palestine, Jews were hostile to the Roman baths beyond the issue of nudity.[74] Another exception regarding female nudity was during certain festivals, such as Veneralia, that included ritual nudity.[75]

India

From around 300 BC Indian mystics have utilized naked ascetism to reject worldly attachments.[citation needed]

China

In much of Asia, traditional dress covers the entire body, similar to Western dress.[76] In stories written in China as early as the 4th Century BCE, nudity is presented as an affront to human dignity, reflecting the belief that "humanness" in Chinese society is not innate, but earned by correct behavior. However, nakedness could also be used by an individual to express contempt for others in their presence. In other stories, the nudity of women, emanating the power of yin, could nullify the yang of aggressive forces.[77]

Late antiquity

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire marked many social changes, including the rise of Christianity. Early Christians generally inherited the norms of dress from Jewish traditions, except for the Adamites, an obscure Christian sect in North Africa originating in the second century who worshiped in the nude, professing to have regained the innocence of Adam.[78] The transformation of European culture during the following centuries was not a unified process. Concepts of individuality and privacy were emerging in the context of cities, each of which was a world of its own. In contrast to the modern city, urban life in late antiquity was not anonymous for the elite, but dependent upon public reputation, which was built upon birth into an upper-class family. The maintenance of social distance between the "well-born few" and their inferiors was of prime importance. For men, maintaining this superiority included sexual dominance based upon fear of effeminacy or emotional dependence, but without regard to sexual orientation. Although clothing was a marker of status in many public situations, nudity at the public baths was an everyday experience where the upper classes maintained their social distinction whether naked or clothed.[79]

It was the establishment of the Christian Church as the state religion that made clothing the necessary sign of a person's rank in society and relationship to the Emperor. [80]

During the first centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, although conversion to Christianity progressed, pagan beliefs regarding the body and sexual conduct remained. The Germanic people of Europe lived in extended families that included several generations plus servants and slaves, in great wooden houses. All slept together, naked, around a common fire.[81]

In the later Middle Ages beginning with the Carolingian period, both men and women dressed from head to foot, going nude only when they swam, bathed, or slept. The Roman baths continued to be used, even in monasteries, but were more often reserved for the ill. People swam in rivers and bathed in hot springs, Charlemagne doing so at Aix-en-Provence with as many as a hundred guests. In some pagan ceremonies, a young girl or woman would undress entirely to call forth the fertility of the fields. However, touching a woman was interfering with this life process, and prohibited. Nudity was sacred for pagans as part of procreation, thus associated only with sex.[82]

The early Christian view was quite different from the pagan, based upon the human body as the creation of God. Until the beginning of the eighth century, Baptism had been performed by full immersion and without clothing in an octagonal basin attached to every cathedral. Converts emerged reborn, so early Christians associated nudity with grace. The elimination of naked Baptism in the 8th century represented the Christian acceptance of the pagan view of nudity is sexual. This led to the clothing of Christ on the Cross, the original depictions being naked, as would have been the case for Roman crucifixions. [83][84]

The late fourth century CE was a period of both Christian conversion and standardization of church teachings, in particular on matters of sex. The dress or nakedness of women that were not deemed respectable was also of lesser importance.[85] A man having sex outside marriage with a respectable woman (adultery) injured third parties: her husband, father, and male relatives. His fornication with an unattached woman, likely a prostitute, courtesan or slave, was a lesser sin since it had no male victims, which in a patriarchal society might mean no victim at all.[86]

Post-classical history

Europe

The period between the ancient and modern world—approximately 500 to 1450 CE—saw an increasingly stratified society in Europe, with attitudes and behavior dependent upon social status. At the beginning of the period, everyone other than the upper classes lived in close quarters and did not have the modern sensitivity to private nudity, but slept and bathed together naked as necessary.[46] The Roman baths in Bath, Somerset, were rebuilt, and used by both sexes without garments until the 15th century.[87] Later in the period, with the emergence of a middle class, clothing in the form of fashion was a significant indicator of class, and thus its lack became a greater source of embarrassment. These attitudes only slowly spread to all of society.[88]

Until the beginning of the eighth century, Christians were baptized naked to represent that they emerged from baptism without sin. The disappearance of nude baptism in the Carolingian era marked the beginning of the sexualization of the body by Christians that had previously been associated with paganism.[83]

In the 13th century theorists dealt with the issue of sexuality, Albertus Magnus favoring a more philosophical view influenced by Aristotle that sex within marriage was a natural act. However, his pupal Thomas Aquinas and others took the view of Saint Augustine that sexual desire was shameful not only as original sin, but that lust was a disorder because it undermined reason. Sexual arousal was deemed so dangerous as to be avoided except for procreation, nudity being particularly taboo, which remained until the Renaissance.[89]

Sects with beliefs similar to the Adamites, who worshiped naked, reemerged in the early 15th century.[90]

Although there is a common misconception that Europeans did not bathe in the Middle Ages, public bath houses were popular until the 16th century, when concern for the spread of disease closed many of them.[91] The first Christians inherited Roman culture, which maintained public water supplies and baths, and bathing remained a popular institution, and a profitable one. Saint Augustine and Clement of Alexandria promoted the virtue of cleanliness. However, the story of Bathsheba was used to warn against the potential for men being seduced by women bathing. Stories of the life of saints emphasized denial of the flesh, and it was the monastic rule that forbade clergy bathing more than three times per year. [92]

In Christian Europe, the parts of the body that were required to be covered in public did not always include the female breasts. In depictions of the Madonna from the 14th century, Mary is shown with one bared breast, symbolic of nourishment and loving care.[93] During a transitional period, there continued to be positive religious images of saints, but also depictions of Eve indicating shame.[94] By 1750, artistic representations of the breast were either erotic or medical. This eroticization of the breast coincided with the persecution of women as witches.[95]

Mesoamerica

The Aztec city Tenōchtitlan reached a population of eighty thousand before the arrival of the Spanish in 1520. Built on an island in Lake Texcoco, it was dependent upon hydraulic engineering for agriculture which also supplied bathing facilities with both steam baths (temazcales) and tubs. In the Yucatán, Mayan men and women bathed in rivers with little concern for modesty. Yet in spite of the number of hot springs in the region, there is no mention of their use for bathing by indigenous peoples. The conquistadors viewed indigenous bathing practices, which included both men and women entering temazcales naked, in terms of paganism and sexual immorality and sought to eradicate them.[96]

Middle East

Clothing in the Middle East, which loosely envelopes the entire body, changed little for centuries in part because it is well-suited for the climate, protecting the body from dust storms while allowing cooling by evaporation. The practice known as veiling of women in public predates Islam in Persia, Syria, and Anatolia. Islamic clothing for men covers the area from the waist to the knees. The Qurʾān provides guidance on the dress of women, but not strict rulings;[97] such rulings may be found in the Hadith. The rules of hijab and Sharia law defines clothing for women as covering the entire body except the face and hands. The nature of the clothing cannot be transparent, revealing what is underneath: "clothed yet naked", nor the clothing of men, such as trousers.[98] Originally, veiling applied only to the wives of Muhammad; however, veiling was adopted by all upper-class women after his death and became a symbol of Muslim identity.[99]

In the medieval period, Islamic norms became more patriarchal, and very concerned with the chastity of women before marriage and fidelity afterward. Women were not only veiled, but segregated from society, with no contact with men not of close kinship, the presence of whom defined the difference between public and private spaces.[100] Of particular concern for both Islam and early Christians, as they extended their control over countries that had previously been part of the Byzantine or Roman empires, was the local custom of public bathing. While Christians were mainly concerned about mixed-gender bathing, which had been common, Islam also prohibited nudity for women in the company of non-Muslim women.[101] In general, the Roman bathing facilities were adapted for separation of the genders, and the bathers retaining at least a loin-cloth rather than being nude, as was the case in Victorian Turkish baths until the end of the 20th century.

Africa

According to Ibn Battuta, female servants and slaves in the Mali Empire during the 14th century would be completely naked.[102] The daughters of the sultan also exposed their breasts in public.[103]

Early modern era

Colonial Americas

Among the Chumash people of southern California, men were usually naked, and women were often topless. Native Americans of the Amazon Basin usually went nude or nearly nude; in many native tribes, the only clothing worn was some device worn by men to clamp the foreskin shut. However, other similar cultures have had different standards. For example, other native North Americans avoided total nudity, and the Native Americans of the mountains and west of South America, such as the Quechuas, kept quite covered. These taboos normally only applied to adults; Native American children often went naked until puberty if the weather permitted (a 10-year-old Pocahontas scandalized the Jamestown settlers by appearing at their camp and cartwheeling in the nude).[104]

In travels in Mali in the 1350s, Muslim scholar Ibn Battuta was shocked by the casual relationships between men and women even at the court of Sultans, and the public nudity of female slaves and servants.[105]

In 1498, at Trinity Island, Trinidad, Christopher Columbus found the women entirely naked, whereas the men wore a light girdle called guayaco. At the same epoch, on the Para Coast of Brazil, the maidens were distinguished from the married women by their absolute nudity. The same absence of costume was observed among the Chaymas of Cumaná, Venezuela, and Du Chaillu noticed the same among the Achiras in Gabon.[citation needed]

The seventeenth century colonization of North America by England followed failed attempts at Roanoke Island that led them to adopt the Spanish template for dealing with the Natives, which was to attack first. This was supported by a view of Indigenous "naked people" as either violent or docile, and a Christian doctrine that killing was justified for those that could not be converted and subjugated.[106]

Early modern Europe

The association of nakedness with shame and anxiety became ambivalent in the Renaissance in Europe. The rediscovered art and writings of ancient Greece offered an alternative tradition of nudity as symbolic of innocence and purity which could be understood in terms of the state of man "before the fall". Subsequently, norms and behaviors surrounding nudity in life and in works of art diverged during the history of individual societies.[107] The meaning of nudity in Europe was also changed in the 1500s by reports of naked inhabitants in the Americas, and the African slaves brought to Italy by the Portuguese. Female slaves were naked when purchased, then clothed and baptized by their new owners. Both slavery and colonialism was the beginning of the modern association of nakedness with savagery.[108]

The medical opinion in the 18th century that bathing in cold water and exposure to the sun had therapeutic benefits created tension between swimmers and defenders of Victorian Christian opinion that the body is shameful, and must be covered when exposed to public view. In addition, mixed bathing with otherwise appropriate costumes was also sinful. Until the early 20th century in New South Wales this led to the enactment of regulations banning public bathing except at limited times, segregated by sex, and in costumes that covered the body from neck to knees.[109]

During the Enlightenment, taboos against nudity began to grow and by the Victorian era, public nudity was considered obscene. In addition to beaches being segregated by gender, bathing machines were also used to allow people who had changed into bathing attire to enter directly into the water.

In England during the 17th to 19th centuries, the clothing of the poor by Christian charity did not extend to those confined to "madhouses" such as Bethlem Royal Hospital, where the inmates were often kept naked and treated harshly.[110]

The Victorian Era is often considered to be entirely restrictive of nudity. However, throughout the United Kingdom in the 19th century, workers in coal mines were naked due to the heat and the narrow tunnels that would catch on clothing. Men and boys worked fully naked, while women and girls (usually employed as "hurriers") would generally only strip to the waist, but in some locations, they were fully naked as well. Testimony before a Parliamentary labour commission revealed that working naked in confined spaces made "sexual vices" a "common occurrence".[111]

Late modern

Japan

The Tokugawa period in Japan (1603–1868) was defined by the social dominance of hereditary classes, with clothing a regulated marker of status and little nudity among the upper classes. However, working populations in both rural and urban areas often dressed only in loincloths, including women in hot weather and while nursing. Lacking baths in their homes, they also frequented public bathhouses where everyone was unclothed together.[112]

Expressing the colonial view of the first Americans to visit, in 1860, Rev. S. Well Williams (interpreter to U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry), wrote:

Modesty, judging from what we see, might be said to be unknown, for the women make no attempt to hide the bosom, and every step shows the leg above the knee; while men generally go with the merest bit of rag, and that not always carefully put on. Naked men and women have both been seen in the streets, and uniformly resort to the same bath house, regardless of all decency. Lewd motions, pictures and talk seem to be the common expression of the viler acts and thoughts of the people, and this to such a degree as to disgust everybody.[113]

With the opening of Japan to European visitors in the Meiji era (1868–1912), the previously normal states of undress, and the custom of mixed public bathing, became an issue for leaders concerned with Japan's international reputation. A law was established with fines for those that violated the ban on undress. Although often ignored or circumvented, the law had the effect of sexualizing the naked body in situations that had not previously been erotic.[114] Modernization included Western-style resorts in the countryside, which immediately became a problem due to mixed-gender bathing continuing to be the norm for Japanese visitors at a time when many Western travelers did not see their own spouses naked. A solution was to segregate the clientele between resorts, which eliminated the benefits of cultural exchange.[115]

Another Japanese tradition was the women free-divers (ama, 海女) who for 2,000 years until the 1960s collected seaweed and shellfish nude or wearing only loincloths.[116] Women farmers often worked bare-breasted during the summer[117] while other workers might be nude.[116]

Europe

Opinions regarding the health benefits of bathing were generally favorable by the 19th century. This led to the establishment of gender segregated public bath houses for those who had no bathing facilities in their homes. In a number of European cities where this included the middle class, some bath houses became social establishments for men. In the United States, where the middle class more often had private baths in their homes, public bath houses were built for the poor, in particular for urban immigrant populations. With the adoption of showers rather than tubs, bathing facilities were added to schools and factories.[118]

For the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, the official poster was created by a distinguished artist. It depicted several naked male athletes (with their genitals obscured) and was for that reason considered too daring for distribution in certain countries. Posters for the Antwerp 1920, Paris 1924, and Helsinki 1952 Summer Olympics also featured nude male figures, evoking the classical origins of the games. The poster for the 1948 Olympics in London featured the Discobolus (Δισκοβόλος), a nude sculpture of a discus thrower.

Germany

In Germany between 1910 and 1935 nudist attitudes toward the body were expressed in sports and in the arts. In the 1910s a number of solo female dancers performed in the nude. Adorée Villany performed the Dance of the Seven Veils, and other stories based upon middle eastern themes, for appreciative upper class audiences.[119] However, after a 1911 performance in Munich, Villany was arrested, along with the theater manager, for indecency. Eventually acquitted, she was forced to leave Bavaria.[120] Olga Desmond's performances combined dance and tableau vivant posing nude in imitation of classical statues.[121]

There were advocates of the health benefits of sun and fresh air that instituted programs of exercise in the nude for children in groups of mixed gender. Adolf Koch founded thirteen Freikörperkultur (FKK) schools.[122] With the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, the nudism movement split ideologically between three groups: the bourgeoisie, the socialists, and the fascists. The bourgeoisie were not ideological, while the socialists adopted the views of Adolf Koch, seeing education and health programs including nudity as part of improving the lives of the working class. While not unanimous in their support, some Nazis used nudity to extol the Aryan race as the standard of beauty, as reflected in the Nazi propaganda film about the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin directed by Leni Riefenstahl, Olympia.[123]

Socialist views of nudity extended to the Soviet Union, where in 1924 an informal organization called the "Down with Shame" movement held mass nude marches in an effort to dispel earlier, "bourgeois" morality.[124][125]

Other countries

In the 1920s naturism took different directions in Scandinavia, France, England, Belgium and the Netherlands. While based on the German model, each county had its own religious, political, and cultural perspectives. Regaining a connection to nature lost during industrialization was a common theme. A distinction was made between the nudity and sexuality in order to appreciate health and beauty of the body without association with "vice, eroticism, and exhibitionism".[126]

Gender distinctions in public behavior

Public swimming pools in the United States were the product of municipal reform movements beginning in the mid-19th century. In New York City, municipal baths and pools were first opened in 1870 not only to improve the health of the inhabitants of tenements, but to control the use of the waterfront by men and boys who violated Victorian norms by behaving boisterously and swimming nude where women might see them from passing boats. This effort had mixed effect, with boys continuing to swim nude in rivers into the 1930s; preferring unsupervised play to rule-bound recreation.[127] Civic leaders had not intended pools to be used for recreation, but for health and sporting activities, which were male only. Initially, working-class men and boys swam in the nude, as had previously been customary in lakes and rivers.[128] Only later were days set aside for use of baths and pools by women.[127]

From 1860 to 1937 men in the UK and America were often required to wear suits that covered the upper torso when swimming where women were present. Early swimsuits made of knitted wool made swimming difficult.[129] In many places, gender segregation was maintained where recreational activities were deemed unladylike, such as particular beaches, rivers, lakes and swimming pools. In England from 1900 to 1919, women were forbidden to bathe within a hundred yards of any male swimmer over the age of twelve. Restrictions in behavior and bathing costumes were slowly relaxed during the 1920s, and by the 1930s, this could result in men swimming nude within the view of women.[130]

In places limited to men, communal nudity in the U.S. and other Western countries was the norm for much of the 20th century.[131] Males have been more likely than females to be expected to swim nude in indoor pools or to share communal showers in school locker rooms with other members of the same sex.[132] These expectations were based on cultural beliefs that females need more privacy than males.[133] Social attitudes at the time maintained that it was healthy and normal for men and boys to be nude around each other and schools, gymnasiums, and other such organizations typically required nude male swimming in part for sanitary reasons due to the use of wool swimsuits.[128] In the 1926 edition of the guidelines on swimming pools by the American Public Health Association (APHA), citing the problem of properly cleaning suits, it was recommended that for pools used only by men that they swim in the nude.[134] This guideline remained until 1962 but continued to be observed by the YMCA and public schools with gender segregated classes into the 1970s.[135][136][137]

The nudity of male children was of less concern, and could occur in mixed gender venues. In 1909 The New York Times reported that at an elementary school swim public competition the 80 lb. division, finding that their suits slowed them down, competed in the nude.[138] As recently as 1996 the YMCA maintained a policy of allowing young children five or under to accompany their parents into the locker room of the opposite gender, which some health care professionals questioned.[139]

Movies, advertisements, and other media frequently showed nude male bathing or swimming. There was less tolerance for female nudity and the same schools and gyms that insisted on wool swimwear being unsanitary for males did not make an exception when women were concerned. Nonetheless, some schools did allow girls to swim nude if they wished. To cite one example, Detroit public schools began allowing nude female swimming in 1947, but ended it after a few weeks following protests from parents. Other schools continued allowing it, but it was never a universally accepted practice as was nude male swimming even though classes were not co-ed. A 1963 article on the elementary school swim program in Troy, New York stated that boys swam nude, but that girls were expected to wear bathing suits, continuing the practice of prior decades.[140] When Title IX implemented equality in education in 1972, pools became co-ed, ending the era of nude swimming.[135] In the 21st century, the practice of boys swimming nude is largely forgotten, or even denied to have ever existed.[136]

Contemporary

Both hippies or other participants in the counterculture of the 1960s embraced nudity as part of their daily routine and to emphasize their rejection of anything artificial. Communes sometimes practiced naturism, bringing unwanted attention from disapproving neighbors.[141] In 1974, an article in The New York Times noted an increase in American tolerance for nudity, both at home and in public, approaching that of Europe. However, some traditional nudists at the time decried the trend as encouraging sexual exhibitionism and voyeurism and threatening the viability of private nudist clubs.[142] In 1998, American attitudes toward sexuality had continued to become more liberal than in prior decades, but the reaction to total nudity in public was generally negative.[143] However, some elements of the counterculture, including nudity, continued with events such as Burning Man.[144]

In hunter-gatherer and pastoral cultures in warm climates nudity or minimal dress had been the social norm for both men and women prior to contact with Western cultures or Islam. A few societies well-adapted to life in isolated regions retain their traditional practices and cultures while having some contact with the developed world.[145]

Many indigenous peoples in Africa and South America train and perform sport competitions naked.[citation needed] For example, the Nuba people in South Sudan and the Xingu tribe in the Amazon region in Brazil wrestle naked. The Dinka, Surma and Mursi peoples in South Sudan and Ethiopia engage in nude stick fights.[citation needed]

Complete or partial nudity for both men and women is still common for Mursi, Surma,[146] Nuba, Karimojong, Kirdi, Dinka and sometimes Maasai people in Africa, as well as Matses, Yanomami, Suruwaha, Xingu, Matis and Galdu people in South America.[citation needed]

In some African and Melanesian cultures, men going completely naked except for a string tied about the waist are considered properly dressed for hunting and other traditional group activities. In a number of tribes in the South Pacific island of New Guinea, men use hard gourdlike pods as penis sheaths. Yet a man without this covering could be considered to be in an embarrassing state of nakedness.

See also

- Christian naturism

- American Gymnosophical Association

- Depictions of nudity

- History of the nude in art

- History of the Rechabites

- Nudity and sexuality

- Nudity in combat

- Timeline of social nudity

References

Notes

- ^ Originally, flagitium meant a public shaming, and later more generally a disgrace

- ^ Varro, De lingua latina 6.8, citing a fragment from the Latin tragedian Accius on Actaeon that plays with the verb video, videre, visum, 'see', and its presumed connection to vis (ablative vi, 'by force') and violare, 'to violate': "He who saw what should not be seen violated that with his eyes" (Cum illud oculis violavit is, qui invidit invidendum)

- ^ Ancient etymology was not a matter of scientific linguistics, but of associative interpretation based on similarity of sound and implications of theology and philosophy[68]

- ^ Causa decoris: Celsus, De medicina 7.25.1A

- ^ noting that some had themselves circumcised again later.[73]

Citations

- ^ Daley 2018.

- ^ Rantala 2007, pp. 1–7.

- ^ Giles 2010.

- ^ Jablonski & Chaplin 2000, pp. 57–106.

- ^ Jablonski 2012.

- ^ Schlebusch 2017.

- ^ Toups et al. 2010, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Hollander 1978, p. 83.

- ^ Leary & Buttermore 2003.

- ^ Beck 2000.

- ^ Asher-Greve & Sweeney 2006, pp. 155–164.

- ^ Batten 2010, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Asher-Greve & Sweeney 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Bahrani 1993.

- ^ Bahrani 1996.

- ^ Asher-Greve & Sweeney 2006, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Batten 2010.

- ^ a b Altenmüller 1998, pp. 406–7.

- ^ Mertz 1990, p. 75.

- ^ Tierney 1999, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Mark 2017.

- ^ a b c Goelet 1993.

- ^ Jones 2015.

- ^ Minoan n.d.

- ^ Mouratidis 1985.

- ^ Kyle 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Villing 2010, p. 40.

- ^ Kyle 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Bonfante 1989.

- ^ Sutton 2009.

- ^ Kosso & Scott 2009, pp. 61–86.

- ^ Kennell 2013.

- ^ Kyle 2014, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Potter 2012, Ch. 25.

- ^ Ariès & Duby 1987, p. 199.

- ^ Cartledge 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Plutarch n.d.

- ^ Polybius n.d.

- ^ Plato 1925.

- ^ Golden 2004, p. 290.

- ^ Kyle 2014, pp. 245–247.

- ^ a b Habinek & Schiesaro 1997, p. 39.

- ^ Cicero 1927, p. 408.

- ^ Ariès & Duby 1987, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Fagan 2002.

- ^ a b Dendle 2004.

- ^ Poliakoff 1993.

- ^ Cicero 1877.

- ^ Younger 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Graf 2005, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Williams 2009, pp. 64, 292 note 12.

- ^ Heskel 2001, p. 138.

- ^ a b Blanshard 2010, p. 24.

- ^ a b Williams 2009, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Juvenal 1918a.

- ^ Juvenal 1918b.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 5ff.

- ^ Stevenson 1998.

- ^ Zanker 1990, pp. 239–240, 249–250.

- ^ Richlin 2002.

- ^ Clarke 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Cohen 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Cameron 2010, p. 725.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria n.d.

- ^ Sharrock 2002, p. 275.

- ^ Clarke 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Fredrick 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Del Bello 2007.

- ^ Plutarch 1914.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 6.

- ^ Fagan 2002, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Schäfer 2003, p. 151.

- ^ Eliav 2010.

- ^ Pasco-Pranger 2019.

- ^ Hansen 2004, pp. 378–380.

- ^ Henry 1999.

- ^ Livingstone 2013.

- ^ Ariès & Duby 1987, The "Wellborn" Few.

- ^ Ariès & Duby 1987, p. 273.

- ^ Ariès & Duby 1987, pp. 464–465.

- ^ Ariès & Duby 1987, pp. 453–455.

- ^ a b Ariès & Duby 1987, pp. 455–456.

- ^ Veyne 1987, p. 455.

- ^ Glancy 2015.

- ^ Harper 2012.

- ^ Byrde 1987.

- ^ Classen 2008.

- ^ Brundage 2009, pp. 420–424.

- ^ Lerner 1972.

- ^ Medievalists 2013.

- ^ Archibald 2012.

- ^ Miles & Lyon 2008, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Miles & Lyon 2008, Part One – The Religious Breast.

- ^ Miles & Lyon 2008, Part Two – The Secular Breast.

- ^ Walsh 2018.

- ^ Laver 1998.

- ^ al-Qaradawi 2013, p. 179.

- ^ Rasmussen 2013.

- ^ Lindsay 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Kosso & Scott 2009, pp. 171–190.

- ^ Byrd 2012, p. 38.

- ^ Meredith 2014, p. 72.

- ^ Strachey 1849, p. 65.

- ^ Bentley 1993.

- ^ Olesen 2009.

- ^ Barcan 2004, chpt. 2.

- ^ Burke 2013.

- ^ Booth 1997, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Andrews 2007b, pp. 131–156.

- ^ FordhamU 2019.

- ^ Kawano 2005, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Miyoshi 2005.

- ^ Kawano 2005, pp. 153–163.

- ^ Brecher 2018.

- ^ a b Downs 1990.

- ^ Martinez 1995.

- ^ Williams 1991, pp. 5–10.

- ^ Toepfer 1997, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Dickinson 2011.

- ^ Toepfer 1997, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Toepfer 1997, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Krüger, Krüger & Treptau 2002.

- ^ Siegelbaum 1992.

- ^ Manaev & Chalyan 2018.

- ^ Peeters 2006.

- ^ a b Adiv 2015.

- ^ a b Wiltse 2003.

- ^ Farrow 2016.

- ^ Horwood 2000.

- ^ HistoricArchive 2019.

- ^ Smithers 1999.

- ^ Senelick 2014.

- ^ Gage 1926.

- ^ a b Andreatta 2017.

- ^ a b Eng 2017.

- ^ Markowitz 2014.

- ^ NYTimes 1909.

- ^ McCombs 1996.

- ^ Mann 1963.

- ^ Miller 1999, pp. 197–199.

- ^ Sterba 1974.

- ^ Layng 1998.

- ^ Holson 2018.

- ^ Stevens 2003.

- ^ Hashim 2014.

Sources

Nudity in general

- Barcan, Ruth (2004). Nudity: A Cultural Anatomy. Berg Publishers. ISBN 1859738729.

- Black, Pamela (2014). "Nudism". In Forsyth, Craig J.; Copes, Heith (eds.). Encyclopedia of Social Deviance. SAGE Publications. pp. 471–472. ISBN 9781483340463.

- Bullough, Vern L.; Bullough, Bonnie (2014). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 449. ISBN 9781135825096.

- Carr-Gomm, Philip (2010). A Brief History of Nakedness. London, UK: Reaktion Books, Limited. ISBN 978-1-86189-729-9. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Martinez, D.P. (1995). "Naked Divers: A Case of Identity and Dress in Japan". In Eicher, Joanne B. (ed.). Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time. Ethnicity and Identity Series. Oxford: Berg. pp. 79–94. doi:10.2752/9781847881342/DRESSETHN0009. ISBN 9781847881342.

Prehistory

- Beck, Margaret (2000). "Female Figurines in the European Upper Paleolithic: Politics and Bias in Archaeological Interpretation". In Rautman, Alison E. (ed.). Reading the Body. Representations and Remains in the Archaeological Record. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 202–214. ISBN 978-0-8122-3521-0. JSTOR j.ctv512z16.20.

- Collard, Mark; Tarle, Lia; Sandgathe, Dennis; Allan, Alexander (2016). "Faunal evidence for a difference in clothing use between Neanderthals and early modern humans in Europe". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 44: 235–246. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2016.07.010. hdl:2164/9989.

- Curry, Andrew (March 2012). "The Cave Art Debate". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Daley, Jason (11 December 2018). "Why Did Humans Lose Their Fur?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Jablonski, Nina G.; Chaplin, George (2000). "The Evolution of Human Skin Coloration". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (1): 57–106. Bibcode:2000JHumE..39...57J. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403. PMID 10896812. S2CID 38445385.

- Giles, James (1 December 2010). "Naked Love: The Evolution of Human Hairlessness". Biological Theory. 5 (4): 326–336. doi:10.1162/BIOT_a_00062. ISSN 1555-5550. S2CID 84164968.

- Hollander, Anne (1978). Seeing Through Clothes. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0140110844.

- Jablonski, Nina G. (1 November 2012). "The Naked Truth". Scientific American.

- Leary, Mark R.; Buttermore, Nicole R. (2003). "The Evolution of the Human Self: Tracing the Natural History of Self-Awareness". Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 33 (4): 365–404. doi:10.1046/j.1468-5914.2003.00223.x.

- Rantala, M. J. (2007). "Evolution of nakedness in Homo sapiens". Journal of Zoology. 273 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00295.x. S2CID 14182894.

- Schlebusch; et al. (3 November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

- Toups, M. A.; Kitchen, A.; Light, J. E.; Reed, D. L. (2010). "Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 3002236. PMID 20823373.

Ancient history

- Adams, Cecil (9 December 2005). "Small Packages". Isthmus; Madison, Wis. Madison, Wis., United States, Madison, Wis. p. 57. ISSN 1081-4043. ProQuest 380968646.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (1998). Egypt: the world of the pharaohs. Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 9783895089138.

- Ariès, Philippe; Duby, Georges, eds. (1987). From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. A History of Private Life. Vol. I. Series Editor Paul Veyne. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39975-7.

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Sweeney, Deborah (2006). "On Nakedness, Nudity, and Gender in Egyptian and Mesopotamian Art". In Schroer, Sylvia (ed.). Images and Gender: Contributions to the Hermeneutics of Reading Ancient Art. Vol. 220. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg. doi:10.5167/uzh-139533. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Bahrani, Zainab (1993). "The Iconography of the Nude in Mesopotamia". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 12 (2): 12–19. doi:10.1086/sou.12.2.23202931. ISSN 0737-4453. S2CID 193110588. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Bahrani, Zainab (1996). "The Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and the Production of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient Art". Oxford Art Journal. 19 (2): 3–16. doi:10.1093/oxartj/19.2.3. ISSN 0142-6540. JSTOR 1360725. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Batten, Alicia J. (2010). "Clothing and Adornment". Biblical Theology Bulletin. 40 (3): 148–59. doi:10.1177/0146107910375547. S2CID 171056202.

- Blanshard, Alastair J. L. (2010). Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-2357-3.

- Bonfante, Larissa (1989). "Nudity as a Costume in Classical Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 93 (4): 543–570. doi:10.2307/505328. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 505328. S2CID 192983153. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2022). "Nude Awakenings: Early Dynastic Nude Female Iconography". Near Eastern Archaeology. 85 (1): 34–43. doi:10.1086/718192. ISSN 1094-2076. S2CID 247253435. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- Cameron, Alan (2010). The Last Pagans of Rome. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-978091-4.

- Carter, Michael (2009). "(Un)Dressed to Kill: Viewing the Retiarius". In Edmondson, Jonathan; Keith, Alison (eds.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-9189-6.

- Cartledge, Paul (2003). Spartan Reflections. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23124-5.

- Clarke, John R. (2002). "Look Who's Laughing at Sex: Men and Women Viewers in the Apodyterium of the Suburban Baths at Pompeii". In Fredrick, David (ed.). The Roman Gaze: Vision, Power, and the Body. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6961-7.

- Corner, Sean (2012). "Did 'Respectable' Women Attend Symposia?". Greece & Rome. 59 (1): 34–45. doi:10.1017/S0017383511000271. ISSN 1477-4550.

- Crowther, Nigel B. (December 1980 – January 1981). "Nudity and Morality: Athletics in Italy". The Classical Journal. 76 (2). The Classical Association of the Middle West and South: 119–123. JSTOR 3297374.

- Del Bello, Davide (2007). Forgotten Paths: Etymology and the Allegorical Mindset. CUA Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1484-9.

- Dendle, Peter (2004). "How Naked Is Juliana?". Philological Quarterly. 83 (4): 355–370. ISSN 0031-7977. ProQuest 211146473. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Fredrick, David (2002). "Invisible Rome". In David Fredrick (ed.). The Roman Gaze: Vision, Power, and the Body. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6961-7.

- Eliav, Yaron Z. (19 August 2010). "Bathhouses As Places of Social and Cultural Interaction". In Hezser, Catherine (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-921643-7. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Fagan, Garrett G. (2002). Bathing in Public in the Roman World. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472088653.

- Glancy, Jennifer A (2015). "The Sexual Use of Slaves: A Response to Kyle Harper on Jewish and Christian Porneia". Journal of Biblical Literature. 134 (1): 215–29. doi:10.1353/jbl.2015.0003. S2CID 160847333.

- Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-53595-3.

- Goelet, Ogden (1993). "Nudity in Ancient Egypt". Notes in the History of Art. 12 (2): 20–31. doi:10.1086/sou.12.2.23202932. S2CID 191394390.

- Graf, Fritz (2005). "Satire in a ritual context". In Kirk Freudenburg (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Roman Satire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82657-0.

- Habinek, Thomas; Schiesaro, Alessandro (1997). "The invention of sexuality in the world-city of Rome". The Roman Cultural Revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58092-2.

- Hadfield, James (10 December 2016). "Last splash: Immodest Japanese tradition of mixed bathing may be on the verge of extinction". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Harper, Kyle (2012). "Porneia: The Making of a Christian Sexual Norm". Journal of Biblical Literature. 131 (2): 363–83. doi:10.2307/23488230. JSTOR 23488230. S2CID 142975618.

- Henry, Eric (1999). "The Social Significance of Nudity in Early China". Fashion Theory. 3 (4): 475–486. doi:10.2752/136270499779476036.

- Heskel, Julia (2001). "Cicero as Evidence for Attitudes to Dress in the Late Republic". In Judith Lynn Sebesta & Larissa Bonfante (ed.). The World of Roman Costume. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299138547.

- Jones, Bernice R. (2015). Ariadne's Threads: The Construction and Significance of Clothes in the Aegean Bronze Age. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-3277-7.

- Kosso, Cynthia; Scott, Anne, eds. (2009). The Nature and Function of Water, Baths, Bathing, and Hygiene from Antiquity Through the Renaissance. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004173576.

- Kamash, Zena (17 November 2010). "Which Way to Look?: Exploring Latrine Use in the Roman World". Toilet. New York University Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814759646.003.0008. ISBN 978-0-8147-5964-6.

- Kennell, Nigel (11 December 2013). "Boys, Girls, Family, and the State at Sparta". In Grubbs, Judith Evans; Parkin, Tim (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. p. 0. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199781546.013.019. ISBN 978-0-19-978154-6. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- Kyle, Donald G. (2014). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Ancient Cultures; v.4 (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-61380-1.

- Laver, James (1998). "Dress | clothing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). "Other "Ways of Seeing": Female Viewers of the Knidian Aphrodite". Helios. 42 (1): 103–122. Bibcode:2015Helio..42..103L. doi:10.1353/hel.2015.0006. ISSN 1935-0228. S2CID 162147069. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Livingstone, E. A., ed. (2013). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199659623.

- Mark, Joshua J. (27 March 2017). "Fashion and Dress in Ancient Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- Mertz, Barbara (1990). Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Peter Bedrick Books. ISBN 9780872262225.

- "Minoan Dress". Encyclopedia of Fashion. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Mouratidis, John (1985). "The Origin of Nudity in Greek Athletics". Journal of Sport History. 12 (3): 213–232. ISSN 0094-1700. JSTOR 43609271.

- Olson, Kelly C. (1999). Fashioning the Female in Roman Antiquity (PhD thesis). United States -- Illinois: The University of Chicago.

- Pasco-Pranger, Molly (1 October 2019). "With the Veil Removed: Women's Public Nudity in the Early Roman Empire". Classical Antiquity. 38 (2): 217–249. doi:10.1525/ca.2019.38.2.217. ISSN 0278-6656. S2CID 213818509.

- Poliakoff, Michael (1993). "'They Should Cover Their Shame': Attitudes Toward Nudity in Greco-Roman Judaism". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 12 (2): 56–62. doi:10.1086/sou.12.2.23202936. ISSN 0737-4453. S2CID 193095954. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Pollock, Susan; Bernbeck, Reinhard (2000). "And They Said, Let Us Make Gods in Our Image:: Gendered Ideologies in Ancient Mesopotamia". In Rautman, Alison E. (ed.). Reading the Body. Representations and Remains in the Archaeological Record. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 150–164. ISBN 978-0-8122-3521-0. JSTOR j.ctv512z16.17. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Potter, David (2012). The Victor's Crown a History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-283-34915-4.

- Reid, Heather (1 October 2020). "Heroic Parthenoi and the Virtues of Independence: A Feminine Philosophical Perspective on the Origins of Women's Sport". Sport, Ethics and Philosophy. 14 (4): 511–524. doi:10.1080/17511321.2020.1756903. ISSN 1751-1321. S2CID 219462673. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Richlin, A. (2002). "Pliny's Brassiere". In L. K. McClure (ed.). Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and Sources. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. pp. 225–256. doi:10.1002/9780470756188.ch8. ISBN 9780470756188.

- Roth, Ann Macy (2021). "Father Earth, Mother Sky: Ancient Egyptian Beliefs About Conception and Fertility". Reading the Body: Representation and Remains in the Archaeological Record. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 187–201. ISBN 9780812235210. JSTOR j.ctv512z16.19.

- Satlow, Michael L. (1997). "Jewish Constructions of Nakedness in Late Antiquity". Journal of Biblical Literature. 116 (3): 429–454. doi:10.2307/3266667. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 3266667.

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30585-3.

- Sharrock, Allison R. (2002). "Looking at Looking: Can You Resist a Reading?". In David Fredrick (ed.). The Roman Gaze: Vision, Power, and the Body. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6961-7.

- Silverman, Eric (2013). A Cultural History of Jewish Dress. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-857-85209-0.

The Five Books of Moses...clearly specify that Jews must adhere to a particular dress code-modesty, for example, and fringes. Clothing, too, served as a "fence" that protected Jews from the profanities and pollutions of the non-Jewish societies in which they dwelled. From this angle, Jews dressed distinctively as God's elect.

- Stevenson, Tom (1998). "The 'Problem' with Nude Honorific Statuary and Portraits in Late Republican and Augustan Rome". Greece & Rome. 45 (1): 45–69. doi:10.1093/gr/45.1.45. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 643207. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Sutton, Robert F. (1 January 2009). Female Bathers and the Emergence of the Female Nude in Greek Art. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2703-2.

- Sweet, Waldo E. (1987). Sport and Recreation in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook with Translations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536483-5.

- Tierney, Tom (1999). Ancient Egyptian Fashions. Mineola, NY: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-40806-4.

- Veyne, Paul, ed. (1987). A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Vol. 1 of 5. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674399747.

- Villing, Alexandra (2010). The Ancient Greeks: Their Lives and Their World. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-985-0.

- Williams, Craig A. (31 December 2009). Roman Homosexuality (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974201-1.

- Younger, John (2004). Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-54702-9.

- Zanker, Paul (1990). The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08124-1.

Classics

- Cicero (1877). "Tusculan Disputations 4.33.70". Translated by Yonge, C. D. New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

The censure of this crime to those is due; Who naked bodies first exposed to view. – Ennius

- Cicero (1927). Tusculan Disputations. Loeb Classical Library 141. Vol. XVIII. Translated by J. E. King. doi:10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-tusculan_disputations.1927.

- Clement of Alexandria (n.d.). "Protrepticus 4.50". Retrieved 23 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link)

- Juvenal (1918a). "Satires 2". Translated by Ramsay, G. G. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Juvenal (1918b). "Satires 8". Translated by Ramsay, G. G. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Plato (1925). "Symposium 182c". Translated by Fowler, Harold N. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Plutarch (1914). "Life of Cato 20.5". Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Plutarch (n.d.). "Lycurgus". The Internet Classics Archive. Translated by Dryden, John. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link)

- Polybius (n.d.). "Histories II.28". uchicago.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link)

Post classical and early modern

- al-Qaradawi, Yusuf (11 October 2013). The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam: الحلال والحرام في الإسلام. The Other Press. ISBN 978-967-0526-00-3.

- Andrews, Jonathan (2007a). "The (un)dress of the mad poor in England, c.1650—1850. Part 1" (PDF). History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 005–24. doi:10.1177/0957154X07067245. ISSN 0957-154X. PMID 17580751. S2CID 25516218.

- Andrews, Jonathan (2007b). "The (un)dress of the mad poor in England, c.1650-1850. Part 2" (PDF). History of Psychiatry. 18 (2): 131–156. doi:10.1177/0957154X06067246. ISSN 0957-154X. PMID 18589927. S2CID 5540344.

- Archibald, Elizabeth (2012). "Bathing, Beauty and Christianity in the Middle Ages". Insights. 5 (1): 17.

- "Dress – The Middle East from the 6th Century". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Brundage, James A. (15 February 2009). Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07789-5.

- Burke, Jill (2013). "Nakedness and Other Peoples: Rethinking the Italian Renaissance Nude". Art History. 36 (4): 714–739. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12029. hdl:20.500.11820/44d4da81-8b9c-4340-9cd5-b08c4ebeacc1. ISSN 0141-6790.

- Byrd, Steven (2012). Calunga and the Legacy of an African Language in Brazil. UNM Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780826350862.

- Byrde, Penelope (1987). "'That Frightful Unbecoming Dress' Clothes for Spa Bathing at Bath". Costume. 21 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1179/cos.1987.21.1.44.

- Chughtai, A.S. "Ibn Battuta – The Great Traveller". Archived from the original on 13 March 2012.

- Classen, Albrecht (2008). "The Cultural Significance of Sexuality in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and Beyond". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). Sexuality in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110209402.

- DeForest, Dallas (2013). Baths and Public Bathing Culture in Late Antiquity, 300-700 (PhD). United States: The Ohio State University. ProQuest 2316003596. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Duby, Georges; Veyne, Paul, eds. (1988). Revelations of the Medieval World. A History of Private Life. Vol. II. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39976-5.

- Duby, Georges; Veyne, Paul, eds. (1989). Passions of the Renaissance. A History of Private Life. Vol. III. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39977-3.

- "Modern History Sourcebook: Women Miners in English Coal Pits". Fordham University. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Kawano, Satsuki (2005). "Japanese Bodies and Western Ways of Seeing in the Late Nineteenth Century". In Masquelier, Adeline (ed.). Dirt, Undress, and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21783-7.

- Lerner, Robert E. (1972). The Heresy of the Free Spirit in the Later Middle Ages. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Lindsay, James E. (2005). Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World. Daily Life through History. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

- Miles, Margaret R.; Lyon, Vanessa (2008). A Complex Delight: The Secularization of the Breast, 1350-1750. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520253483.

- Walsh, Casey (9 March 2018). "Virtuous Waters: Mineral Springs, Bathing, and Infrastructure in Mexico". Bathing and Domination in the Early Modern Atlantic World. University of California Press. pp. 15–33. doi:10.1525/9780520965393-004. ISBN 978-0-520-96539-3. S2CID 243754145. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Did people in the Middle Ages take baths?". Medievalists.net. 13 April 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

Colonialism

- Bastian, Misty L (2005). "The Naked and the Nude: Historically Multiple Meanings of Oto (Undress) in Southeastern Nigeria". In Masquelier, Adeline (ed.). Dirt, Undress, and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21783-7.

- Bentley, Jerry H. (1993). Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507639-4.

- Hansen, Karen Tranberg (2004). "The World in Dress: Anthropological Perspectives on Clothing, Fashion, and Culture". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 369–392. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143805. ISSN 0084-6570. ProQuest 199841144.

- Hutnyk, John (1 July 1990). "Comparative Anthropology and Evans-Pritchard's Nuer Photography". Critique of Anthropology. 10 (1): 81–102. doi:10.1177/0308275X9001000105. ISSN 0308-275X. S2CID 145594464.

- Jacobus X (1937). Untrodden fields of anthropology: by Dr. Jacobus(pseud.); based on the diaries of his thirty years' practice as a French government army-surgeon and physician in Asia, Oceania, America, Africa, recording his experiences, experiments and discoveries in the sex relations and the racial practices of the arts of love in the sex life of the strange peoples of four continents. Vol. 2. New York: Falstaff Press.

- Levine, Philippa (1 March 2017). "Naked Natives and Noble Savages: The Cultural Work of Nakedness in Imperial Britain". In Crosbie, Barry; Hampton, Mark (eds.). The Cultural Construction of the British World. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-78499-691-8.

- Olesen, Jan (2009). "'Mercyfull Warres Agaynst These Naked People': The Discourse of Violence in the Early Americas". Canadian Review of American Studies. 39 (3): 253–72. doi:10.3138/cras.39.3.253.

- Masquelier, Adeline Marie (2005a). Dirt, Undress, and Difference Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253111536.

- Meredith, Martin (2014). Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000 Year History of Wealth, Greed and Endeavour. Simon and Schuster. p. 72. ISBN 9781471135460.

- Miyoshi, Masao (2005). As We Saw Them: The First Japanese Embassy to the United States. Paul Dry Books. ISBN 978-1-58988-023-8.

- Stevens, Scott Manning (2003). "New World Contacts and the Trope of the 'Naked Savage". In Elizabeth D. Harvey (ed.). Sensible Flesh: On Touch in Early Modern Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 124–140. ISBN 9780812293630.

- Strachey, William (1849) [composed c. 1612]. The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 65. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Tallie, T. J. (2016). "Sartorial Settlement: The Mission Field and Transformation in Colonial Natal, 1850-1897". Journal of World History. 27 (3): 389–410. doi:10.1353/jwh.2016.0114. ISSN 1045-6007. S2CID 151700116.

- Tcherkézoff, Serge (2008). "Sacred Cloth and Sacred Women. on Cloth, Gifts and Nudity in Tahitian First Contacts:: A Culture of 'Wrapping-In'". First Contacts in Polynesia. The Samoan Case (1722-1848) Western Misunderstandings about Sexuality and Divinity. ANU Press. pp. 159–186. ISBN 978-1-921536-01-4. JSTOR j.ctt24h2mx.15.

- Vincent, Susan (2013). "From the Cradle to the Grave: Clothing and the early modern body". In Sarah Toulalan & Kate Fisher (ed.). The Routledge History of Sex and the Body: 1500 to the Present. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47237-1.

- Wiener, Margaret (2005). "Breasts. (Un)Dress, and Modernist Desires in Balinese-Tourist Encounter". In Masquelier, Adeline (ed.). Dirt, Undress, and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21783-7.

Late modern and contemporary

- Adiv, Naomi (2015). "Paidia meets Ludus: New York City Municipal Pools and the Infrastructure of Play". Social Science History. 39 (3): 431–452. doi:10.1017/ssh.2015.64. ISSN 0145-5532. S2CID 145107499. ProQuest 1986368839.

- Andreatta, David (22 September 2017). "When boys swam nude in gym class". Democrat and Chronicle.

- Booth, Douglas (1997). "Nudes in the Sand and Perverts in the Dunes". Journal of Australian Studies. 21 (53): 170–182. doi:10.1080/14443059709387326. ISSN 1444-3058.

- Cohen, Beth (2003). "Divesting the Female Breast of Clothes in Classical Sculpture". In Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow; Claire L. Lyons (eds.). Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-60386-2.

- Darcy, Jane (3 July 2020). "Promiscuous throng: The 'indecent' manner of sea-bathing in the nineteenth century". TLS. Times Literary Supplement (6118): 4–6. ISSN 0307-661X. Gale A632220975.

- Dickinson, Edward Ross (1 January 2011). "Must We Dance Naked?; Art, Beauty, and Law in Munich and Paris, 1911-1913". Journal of the History of Sexuality. Gale A247037121.

- Dillinger, Hannah (28 April 2019). "When Boys Swam Naked". Associated Press News. Greenwich. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Downs, James F. (1 December 1990). "Nudity in Japanese Visual Media: A Cross-Cultural Observation". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 19 (6): 583–594. doi:10.1007/BF01542467. ISSN 0004-0002. PMID 2082862. S2CID 45164858. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Eng, Monica (10 September 2017). "Baring It All: Why Boys Swam Naked in Chicago Schools". WBEZ.

- Farrow, Abbie (16 February 2016). "The History of Men's Swimwear". Simply Swim UK. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Gage, Stephen (1926). "Swimming Pools and Other Public Bathing Places". American Journal of Public Health. 16 (12): 1186–1201. doi:10.2105/AJPH.16.12.1186. PMC 1321491. PMID 18012021.

- Hashim, Yusuf (24 September 2014). "Fresh Blood Anyone ? Breakfast with the Suris of Surma in Ethiopia". PhotoSafari. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- Holson, Laura M. (31 August 2018). "How Burning Man Has Evolved Over Three Decades". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Horwood, Catherine (1 December 2000). "'Girls who arouse dangerous passions': women and bathing, 1900-39". Women's History Review. 9 (4): 653–673. doi:10.1080/09612020000200265. ISSN 0961-2025. S2CID 142190288.

- Krüger, A.; Krüger, F.; Treptau, S. (2002). "Nudism in Nazi Germany: Indecent Behaviour or Physical Culture for the Well-Being of the Nation". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 19 (4): 33–54. doi:10.1080/714001799. S2CID 145116232.

- Layng, Anthony (1998). "Confronting the Public Nudity Taboo". USA Today Magazine. Vol. 126, no. 2634. p. 24.

- LeValley, Paul (2017). "Nude Swimming in School". Nude & Natural. Vol. 37, no. 1. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- McCombs, Phil (22 November 1996). "Kids in the Locker Room Discomfort Over Mixed Nudity at the Y". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 12 October 2020.