Hawaiian Kingdom

Kingdom of Hawaiʻi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1795–1894 | |||||||||

| Motto: Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono | |||||||||

| Anthem: Hawaiʻi Ponoʻi | |||||||||

Kingdom of Hawaii | |||||||||

| Capital | Lahaina (until 1845) Honolulu (from 1845) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Hawaiian, English | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

| Provisional Government | |||||||||

• 1893-1894 | Committee of Safety | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Inception | 1795 | ||||||||

| January 17, 1893 | |||||||||

| July 4, 1894 1894 | |||||||||

| Currency | U.S. dollar, Hawaiian dollar (1879) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

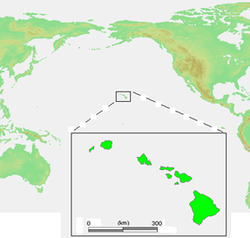

The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was established during the years 1795 to 1810 with the subjugation of the smaller independent chiefdoms of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi and Kauaʻi by the chiefdom of Hawaiʻi (or the "Big Island") into one unified government.

Formation

Through swift and bloody battles, led by a warrior chief later immortalized as Kamehameha the Great, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was established with the help of such British sailors as John Young and Alexander Adams and western weapons. Although successful in attacking both Oʻahu and Maui, he failed to secure a victory in Kauaʻi, his effort hampered by a storm. Eventually, Kauaʻi's chief swore allegiance to Kamehameha's rule. The unification ended the feudal society of the Hawaiian islands transforming it into a "modern", independent constitutional monarchy crafted in the tradition of European empires.

Government

Government in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was transformed in phases, each phase created by the promulgation of the constitutions of 1840, 1852, 1864 and 1887. Each successive constitution can be seen as a decline in the power of the monarch in favor of popularly elected representative government. The head of state and head of government in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was the monarch. He or she oversaw the Privy Council which was charged with administration. A royal cabinet, the Privy Council consisted of ministers in charge of departments much like that of the extant British political system, on which it was based. These ministers also acted as the monarch's primary advisors.

The 1840 Constitution created a bicameral parliament in charge of legislation. The two houses of the legislature were the House of Representatives (directly elected by popular vote) and the House of Nobles (appointed by the monarch with the advice of the Cabinet). The same constitution created a judiciary, charged with overseeing the courts and interpretation of laws. The Supreme Court was led by the Chief Justice, appointed by the monarch with the advice of the Cabinet.

The islands of Hawaiʻi were divided into smaller administrative divisions: Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi. Kauaʻi region included Niʻihau, while Maui region included Kahoʻolawe, Lānaʻi and Molokaʻi. Each administrative region was governed by a governor appointed by the monarch.

Kamehameha Dynasty

From 1810 to 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was ruled by two major dynastic families: the Kamehameha Dynasty and the Kalākaua Dynasty. Five members of the Kamehameha family would lead the government as its king. Two of them, Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), were direct sons of Kamehameha the Great himself. For a period between Liholiho and Kauikeaouli's reigns, the primary wife of Kamehameha the Great, Queen Kaʻahumanu, ruled as Queen Regent and Kuhina Nui, or Prime Minister.

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family tragically ended in 1872 with the death of Lot (Kamehameha V). Upon his deathbed, he summoned Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to declare his intentions of making her heir to the throne. She was the last direct Kamehameha family member surviving. She refused the crown and throne in favor of a private life with her husband, Charles Reed Bishop. Lot died before naming an alternative heir.

The Paulet Affair (1843)

On Monday, the 13th February 1843, Lord George Paulet, of HMS Carysfort, attempted to annex the islands for alleged insults and malpractices against British subjects.[1] Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25, writing:

- Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands?'

- Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified.

- Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843.

- Kamehameha III.

- Kekauluohi.[2]

Dr. Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the Minister of Finance for the Kingdom of Hawaii, secretly arranged for General J.F.B. Marshall to be the King's envoy to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet's actions.[3] Marshall was able to secretly convey the Kingdom's complaint to the Vice Consul of Britain in Tepec, posing as a commercial agent of Ladd & Co., a company with friendly relations with the Kingdom.

Marshall's complaint was forwarded to Rear Admiral Thomas, Paulet's commanding officer, who arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843 on H.B.M.S. Dublin from Valparaiso, Chile. Admiral Thomas apologized to Kamehameha III for Paulet's actions, and restored Hawaiian sovereignty on the 31st of July, 1843.

On the 28th of November, 1843, a joint declaration by the governments of France and England declared they would "consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, neither directly nor under the title of protectorate, nor under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed." [4] The United States notably declined to join with France and England in this statement.

Elected monarchy

The refusal of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to take the crown and throne as Queen of Hawaiʻi forced the legislature of the Kingdom to declare an election to fill the royal vacancy. From 1872 to 1873, several distant relatives of the Kamehameha line were nominated. In a ceremonial popular vote, and a unanimous legislative vote, William C. Lunalilo (1873-1874) became Hawaiʻi's first of two elected monarchs.

Kalākaua Dynasty

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. He died unexpectedly after less than a year as King of Hawaiʻi. Once again, the legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was forced to declare an election to fill the royal vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kalākaua. The 1874 election was opined to be one of the nastiest political campaign seasons in Hawaiʻi history. Both candidates resorted to mudslinging and rumors. David Kalākaua was elected the second elected King of Hawaiʻi, but without the same ceremonial popular vote Lunalilo had. The choice of the legislature was so controversial following his ascension to the throne that U.S. troops were called upon to suppress rioting that had broken out in protest of his win over Emma.

Hoping to avoid uncertainty in the monarchy's future, Kalākaua proclaimed several heirs to the throne and defined a royal line of succession. His sister Liliʻuokalani would succeed the throne upon Kalākaua's death. It was indicated that Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani would follow. If she could not produce an heir by birth, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole would rule after her.

"Bayonet" Constitution of 1887

In 1887, a constitution was drafted by Lorrin A. Thurston, Minister of Interior under King David Kalākaua. The constitution was proclaimed by the king after a mass meeting of 3,000 residents, including an armed militia, demanded he either sign it or be deposed. The document created a constitutional monarchy like Great Britain, stripping the King of most of his personal authority, empowering the Legislature, and establishing cabinet government. It has since become widely known as the "Bayonet Constitution", a nickname coined by its opponents because of the threat of force used to gain Kalākaua's cooperation.

The 1887 constitution empowered the citizenry to elect members of the House of Nobles (who had previously been appointed by the King). It increased the value of property a citizen must own to be eligible to vote, above what the previous Constitution of 1864 had required. One result was to deny voting rights to poor native Hawaiians and Europeans who previously could vote. It guaranteed a voting monopoly by native Hawaiians and Europeans, by denying voting rights to Asians who comprised a large proportion of the population (A few Japanese and some Chinese had previously become naturalized as subjects of the Kingdom and now lost voting rights they had previously enjoyed.) Americans and other Europeans in Hawaiʻi were also given full voting rights without the need for Hawaiian citizenship. The Bayonet Constitution continued allowing the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but stripped him of the power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature.

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy

The neutrality of this section is disputed. |

Queen Liliʻuokalani was selected as the successor to King Kalākaua by Kalākaua upon his election in 1874. During her brother's reign the monarchy was left impotent by the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. In response to royal corruption, including an opium license bribery scandal, David Kalākaua was ordered under threat of force to sign the constitution stripping the monarchy of much of its power in favor of an administration controlled by the Legislature. Some claim this constitution was the opening salvo to the end of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

Liliʻuokalani's Constitution

In 1891, Kalākaua died and his sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne. She came to power in the middle of an economic crisis precipitated in part by the McKinley Tariff. By rescinding the Reciprocity Treaty of 1874, the new tariff eliminated the previous advantage Hawaiian sugar exporters enjoyed vis a vis other international producers in trade to U.S. markets; the result was a crippling of the Hawaiian sugar industry. Many Hawaiian businesses and citizens were feeling the pressures of the loss of revenue, and Liliʻuokalani proposed a lottery system and opium licensing to bring in additional revenue for the Hawaiian government. Her ministers, and even her closest friends, were sorely disappointed at the thought and tried to dissuade her from pursuing the bills. Her support of the lottery and opium bills were used against her in the looming constitutional crisis.

Liliʻuokalani's chief desire was to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 Constitution, under which she came to power after her brother's death. The queen launched a campaign resulting in a petition from some Hawaiian subjects to proclaim a new Constitution. When she informed her cabinet of her plans, they refused to support her.

Those citizens and residents who in 1887 had forced Kalākaua to sign the "Bayonet Constitution" became alarmed that the queen was planning to unilaterally proclaim her new Constitution. They were informed of the queen's plans by her own recently appointed cabinet.[5] The cabinet ministers were reported to have feared for their safety after upsetting the queen by not supporting her plans.[6]

The Overthrow

In 1893, local businessmen and politicians, primarily of American and European ancestry but including native-born Hawaiian subjects of foreign descent, organized in response to an attempt by Liliʻuokalani to abrogate the 1887 constitution, overthrew the queen, her cabinet and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

There was likely no single motivation behind the coup d'etat. Russ states that the overthrow was motivated by the fact that "the Royal Government under Kalakaua and Liliuokalani was inefficient, corrupt, and undependable."[8] Other historians suggest that businessmen were in favor of overthrow and annexation to the U.S. in order to benefit from more favorable trade conditions with its main export market.[9][10][11][12] The proximate cause, however, was in response to Liliʻuokalani's attempt to promulgate a new constitution.

The McKinley Tariff of 1891 eliminated the previously highly favorable trade terms for Hawaii's sugar exports, a main component of the economy. The significance of this economic downturn as a motivation for the overthrow has been questioned by Richard D. Weigle who wrote in the February 1947 Pacific Historical Review:

In actual fact the planters comprised a vigorous bloc of opinion opposing annexation to the United States, and the key to their attitude lies in their dependence upon contract labor. Annexation to the United States would mean conformity to American immigration legislation and the cessation of the influx of laborers from Asiatic countries so necessary to the life of the plantations. [13]

The major events of the overthrow took place between January 15 to January 17, 1893, when 1,500 armed local people, mostly Euro-Americans under the leadership of the thirteen-member Committee of Safety, organized the Honolulu Rifles to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. They quickly took over government buildings, disarmed the Royal Guard, and declared a Provisional Government.

As these events were unfolding, U.S. Minister John L. Stevens requested that troops be landed. Captain Wiltse of the USS Boston ordered 162 sailors and Marines to come ashore with rifles and Gatling guns, "for the purpose of protecting our legation, consulate, and the lives and property of American citizens, and to assist in preserving public order."[14] Stevens was accused of ordering the landing himself on his own authority, and inappropriately using his discretion. Russ states: "One fact, and one only, lessens Steven's guilt...the landing of the American force was the work entirely of Wiltse, rather than of Stevens...Wiltse gave Young orders to get his men ready to land."[15]

Historian William Russ concluded that "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself"[16]. Russ also states that Lieutenant Commander W.T. Swinburne, executive officer of the Boston and the senior officer on shore, "maintained stoutly that Wiltse had landed the forces to protect American property; and that if the Queen had asked for assistance, she would have received it."[17]

On July 17, 1893, Sanford B. Dole and his committee declared itself the Provisional Government "to rule until annexation by the United States."[18] On July 4, 1894 the Republic of Hawaiʻi was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. Later, after a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds after an attempted counter-rebellion in 1895, Queen Liliʻuokalani was placed under arrest, tried by a military tribunal of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, convicted of misprision of treason and then imprisoned in her own home.

The Republic of Hawaii succeeded in its goal when in 1898, Congress approved a joint resolution of annexation creating the U.S. Territory of Hawaiʻi. This followed the precedent of Texas which was also annexed by a joint resolution of Congress. Dole was appointed to be the first governor of the Territory of Hawaii.

The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and the subsequent annexation of Hawaiʻi has recently been cited as the first major instance of American imperialism in a book by Stephen Kinzer, a New York Times foreign correspondent.[19] Historian William Russ describes Hawaii's annexation as incidental to the imperial struggle with Spain, stating, "Such an adventitious circumstance as a Spanish-American War - which finally brought about the act of annexation - was something the aspirants to the union could never have foreseen during most of their long struggle...The five-year fight against tremendous odds to win annexation when the annexer apparently did not want the annexee is rather unique."[20]

Royal estates

Early in its history, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was governed from several locations including coastal towns on the islands of Hawaiʻi and Maui (Lāhainā). It wasn't until the reign of Kamehameha III that a capital was established in Honolulu on the Island of Oʻahu.

By the time Kamehameha V was king, he saw the need to build a royal palace fitting of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi's new found prosperity and standing with the royals of other nations. He commissioned the building of the palace at Aliʻiōlani Hale. He died before it was completed. Today, the palace houses the Supreme Court of the State of Hawaiʻi.

David Kalākaua shared the dream of Kamehameha V to build a palace, and eagerly desired the trappings of European royalty. He commissioned the construction of ʻIolani Palace from which he and his successor would govern. In later years, the palace would become his sister's makeshift prison under guard by the U.S. Armed Forces, the site of the official raising of the U.S. flag during annexation, and then the site of the territorial governor's and legislature's offices.

Palaces

- ʻĀinahau, Home of Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani

- Aliʻiōlani Hale, Originally designed as a Palace for Kamehameha V, although Kamehameha V later decided to convert the building into a government building during construction

- Hanaiakamalama, Summer Palace of Queen Emma

- Huliheʻe Palace, Palace of Princess Ruth

- Keōua Hale, Palace of Princess Ruth

- ʻIolani Palace, Palace of the Kalākaua Dynasty

Royal grounds

Other notable Hawaiian Royals

Kamehameha Dynasty

- Bernice Pauahi Bishop, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Kaʻahumanu, Queen Regent of Hawaiʻi

- Kalama Hakaleleponi Kapakuhaili, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Victoria Kamamalu, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Ruth Keʻelikōlani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Keopuolani, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Kinaʻu, Queen Regent of Hawaiʻi

- Emma Rooke, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Albert Kamehameha, Crown Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Elizabeth Kekaaniau, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Theresa Owana Kaohelelani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

Kalākaua Dynasty

- Victoria Kaʻiulani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaʻole, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Julia Kapiʻolani, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Abigail Campbell Kawananakoa, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- David Kawananakoa, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- William Pitt Leleiohoku, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Miriam K. Likelike, Princess of Hawaiʻi

Other notable Hawaiians

Authors and artists

- Henri Berger, composer

- Robert Louis Stevenson, author

Civil leaders

- John Adams Kuakini, governor

- Charles Reed Bishop, businessman and philanthropist

- James Campbell, businessman and philanthropist

- Archibald Cleghorn, businessman and royal consort

- Sanford B. Dole, chief justice

- John Owen Dominis, governor and royal consort

- Gerrit P. Judd, royal advisor

- Kuini Liliha, governor

- Lorrin A. Thurston, lawyer and publisher

- Robert William Wilcox, soldier

- John Young, royal advisor

- Benjamin Dillingham, businessman and industrialist

- Asher B. Bates, Attorney General

Religious leaders

- Father Damien, Catholic missionary

- Louis Maigret, Catholic bishop

- Thomas Nettleship Staley, Anglican bishop

- Archpriest Jacob Korchinsky, Russian Orthodox Missionary Priest (Murdered by the Soviets)

See also

- Orthodox Church in Hawaii, History of the Orthodox Christian Church in the Hawaiian Islands

References

- ^ http://www.history.navy.mil/docs/wwii/pearl/hawaii.htm

- ^ The Morgan Report, p500-503

- ^ http://www.alohaquest.com/arbitration/news_polynesian_0011b.htm

- ^ The Morgan Report, p503-517

- ^ Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Appendix A "The three ministers left Mr. Parker to try to dissuade me from my purpose; and in the meantime they all (Peterson, Cornwell, and Colburn) went to the government building to inform Thurston and his part of the stand I took."

- ^ Morgan Report, p804-805 "Every one knows how quickly Colburn and Peterson, when they could escape from the palace, called for help from Thurston and others, and how afraid Colburn was to go back to the palace."

- ^ U.S. Navy History site

- ^ The Hawaiian Revolution, by William Russ, Jr. p.349

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen. (2006). Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq.

- ^ Stevens, Sylvester K. (1968) American Expansion in Hawaii, 1842-1898. New York: Russell & Russell. (p. 228)

- ^ Dougherty, Michael. (1992). To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian History. (p. 167 - 168)

- ^ La Croix, Sumner and Christopher Grandy. (March 1997). "The Political Instability of Reciprocal Trade and the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom" in The Journal of Economic History 57:161-189.

- ^ Wiegle, The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 16, No. 1. (Feb., 1947), p.47 Sugar and the Hawaiian Revolution

- ^ The Morgan Report, p. 834

- ^ Russ, William Adam. 1992. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). p. 105.

- ^ Russ, William Adam. 1992. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). p. 350.

- ^ Russ, William Adam. 1992. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). p. 333. Swinburne testified before the Morgan Committee that he told the revolutionary forces, “If the Queen calls upon me to preserve order, I am going to do it.” The Morgan Report, p. 830

- ^ Russ, William Adam. 1992. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). p. 90.

- ^ Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq by Stephen Kinzer, 2006

- ^ The Hawaiian Republic, by William Russ, Jr. p 372

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Hawaii |

|---|

| Topics |