Dutch Formosa

Government of Formosa Gouvernement Formosa 台灣政府 Táiwān zhèngfǔ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1624–1662 | |||||||||||

Location in East Asia | |||||||||||

| Status | Dutch colony | ||||||||||

| Capital | Fort Zeelandia | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch, Formosan languages | ||||||||||

| Religion | Protestantism (Dutch Reformed Church) | ||||||||||

| Government | Colony | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1624–1625 | Marten Sonk | ||||||||||

• 1656–1662 | Frederick Coyett | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Discovery | ||||||||||

• Established | 1624 | ||||||||||

| 1661–1662 | |||||||||||

• Surrender of Fort Zeelandia | February 1, 1662 1662 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Dutch guilder | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Dutch Formosa refers to the period of colonial Dutch government on Formosa (now known as Taiwan), lasting from 1624 to 1662. In the context of the Age of Discovery the Dutch East India Company established its presence on Taiwan to trade with China and Japan, and also to interdict Portuguese and Spanish trade and colonial activities in East Asia.

The time of Dutch rule saw economic development in Taiwan, including both large-scale hunting of deer and the cultivation of rice and sugar by imported labour from Fujian in China. The government also attempted to convert the aboriginal inhabitants to Christianity and suppress some cultural activities they found disagreeable (such as forced abortion and habitual nakedness), in other words, to "civilise" the inhabitants of the island.

However, they were not universally welcomed and uprisings by both aborigines and recent Han Chinese arrivals were crushed brutally by the Dutch military on more than one occasion. The colonial period was brought to an end by the invasion of Koxinga's army after just 37 years.

History

Background

At the beginning of the 17th century the forces of Catholic Spain and Portugal were in opposition to those of Protestant Holland and England, often resulting in open warfare in Europe and in their possessions in Asia. The Dutch first attempted to trade with China in 1601[1] but were rebuffed by the Chinese authorities, who were already engaged in trade with the Portuguese at Macao. In a 1604 expedition from Batavia (the central base of the Dutch in Asia), Admiral van Warwijk set out to attack Macao, but his force was waylaid by a typhoon, driving them to the Pescadores (now known as Penghu). Once there, the admiral attempted to negotiate trade terms with the Chinese on the mainland, but was asked to pay an exorbitant fee for the privilege of an interview. Surrounded by a vastly superior Chinese fleet, he left without achieving any of his aims.[1]

In 1622 after another unsuccessful Dutch attack on Macao the fleet sailed to the Pescadores, this time intentionally, and proceeded to set up a base there at Makung. They built a fort there with forced labour recruited from the local Chinese population; their oversight was reportedly so severe and rations so short that 1,300 of the 1,500 Chinese enslaved died in the process of construction.[2] However, the Ming authorities warned the Dutch that the Pescadores were Chinese territory, and suggested that they instead move to Taiwan and establish themselves there.

The same year a ship named the Golden Lion (Old Dutch: Gouden Leeuw) was wrecked at Lamey just off the southwest coast of Taiwan; the survivors were slaughtered by the native inhabitants.[3] The following year Dutch traders in search of an Asian base first arrived on the island, intending to use the island as a station for Dutch commerce with Japan and the coastal areas of China.

Early years (1624–1625)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Growing control, pacification of the aborigines (1626–1636)

The first order of business was to punish villages that had violently opposed the Dutch and unite the aborigines in allegiance with the VOC. The first punitive expedition was against the villages of Bakloan and Mattau, north of Saccam near Tayowan. The Mattau campaign had been easier than expected and the tribe submitted after having their village razed by fire. The campaign also served as a threat to other villages from Tirosen (Chiayi) to Longkiau (Hengchun).

Consolidation and the ousting of the Spanish (1636–1642)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Growing Chinese presence and the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion (1643–1659)

The Dutch began to encourage large-scale Chinese immigration to the island, mainly from Fujian. Most of the immigrants were young single males who were discouraged from staying on the island often referred to by Han as "The Gate of Hell" for its reputation in taking the lives of sailors and explorers.[4] After one uprising by Han Chinese in 1640, the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652 saw an organised insurrection against the Dutch, fuelled by anger over punitive taxes and corrupt officials. The Dutch again put down the revolt hard, with fully 25% of those participating in the rebellion being killed over a period of a couple of weeks.[5]

Siege of Zeelandia and the end of Dutch government on Formosa (1660–1662)

In 1661, a naval fleet of 1000 warships, led by the Ming loyalist Koxinga, landed at Lu'ermen to attack Taiwan in order to destroy and oust the Dutch from Zeelandia. Following a nine month siege, Koxinga captured the Dutch Fort Zeelandia and defeated the Dutch. Koxinga then forced the Dutch Government to sign a peace treaty at Zeelandia on 1 February 1662, and leave Taiwan. From then on, Taiwan became Koxinga's base for the Kingdom of Tungning.

Government

The Dutch claimed the entirety of the island, but because of the inaccessibility of the central mountain range the extent of their control was limited to the plains on the west coast. This territory was acquired from 1624 to 1642, with most of the villages being required to swear allegiance to the Dutch and then largely being left to govern themselves. The manner of acknowledging Dutch lordship was to bring a small native plant (often betel nut or coconut) planted in earth from that particular town to the Governor, signifying the granting of the land to the Dutch. The Governor would then award the village leader a robe and a staff as symbols of office and a Prinsenvlag ("Prince's Flag", the flag of William the Silent) to display in their village.

Governor of Formosa

The Governor of Formosa (Dutch: Gouverneur van Formosa; Chinese: 台灣長官) was the head of government. Appointed by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia), the Governor of Formosa was empowered to legislate, collect taxes, wage war and declare peace on behalf of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and therefore by extension the Dutch state.

He was assisted in his duties by the Council of Tayouan, a group made up of the various worthies in residence in Tayouan. The President of this council was the second-in-command to the Governor, and would take over his duties if the Governor died or was incapacitated. The Governor's residence was in Fort Zeelandia on Tayouan (then an island, now the Anping District of Tainan City). There were a total of twelve Governors during the Dutch colonial era.[6]

Economy

The Tayouan factory (as VOC trading posts were called) was the second-most profitable factory in the whole of the Dutch East Indies (after the post at Hirado/Dejima).[7] Benefitting from triangular trade between themselves, the Chinese and the Japanese, plus exploiting the natural resources of Formosa, the Dutch were able to turn the malarial sub-tropical bay into a lucrative asset. A cash economy was introduced (using the Dutch guilder) and the period also saw the first serious attempts in the island's history to develop it economically.[8]

Trade

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Hunting

The Dutch originally sought to use their castle Fort Zeelandia at Tayowan (Anping) as a trading base between Japan and China, but soon realized the potential of the huge deer populations that roamed in herds of thousands along the alluvial plains of Taiwan's western regions. Deer were in high demand by the Japanese who were willing to pay premium for use of the hides in samurai armor. Other parts of the deer were sold to Chinese traders for meat and medical use. The Dutch paid aborigines for the deer brought to them and tried to manage the deer stocks to keep up with demand. Unfortunately the deer the aborigines had relied on for their livelihoods began to disappear forcing the aborigines to adopt new means of survival.

Agriculture

The Dutch also employed Chinese to farm sugarcane and rice for export, some of these rice and sugarcane reached as far as the markets of Persia.[9] Attempts to persuade aboriginal tribesmen to give up hunting and adopt a sedentary farming lifestyle were unsuccessful because

for them, farming had two major drawbacks: first, according to the traditional sexual division of labor, it was women's work; second, it was labor-intensive drudgery.[10]

The Dutch therefore imported labour from China, and the era was the first to see mass Chinese immigration to the island, with one commentator estimating that 50-60,000 Chinese settled in Taiwan during the 37 years of Dutch rule.[11] These settlers were encouraged with free transportation to the island, often on Dutch ships, and tools, oxen and seed to start farming.[8] In return, the Dutch took a tenth of agricultural production as a tax.[8]

Head tax

A head tax was levied on all Chinese residents over the age of six.[12] This tax was considered particularly burdensome by the Chinese as their had been no taxation prior to Dutch occupation of the island. Coupled with restrictive land tenancy policies and extortion by Dutch soldiers, the tax provided grounds for the major insurrections of 1640 and 1652.[12]

Religion

One of the key pillars of the Dutch colonial era was conversion of the natives to Christianity. From the descriptions of the early missionaries, the native religion was animist in nature, in one case presided over by priestesses called Inibs.

The Formosans also practiced various activities which the Dutch perceived as sinful or at least uncivilised, including mandatory abortion (by massage) for women under 37[13], frequent marital infidelity[13], non-observation of the Sabbath and general nakedness.

Education

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Legacy

Today, their legacy in Taiwan is visible in Anping District of Tainan City where the remains of their Castle Zeelandia are preserved, in Tainan City itself where their Fort Provintia is still the main structure of what is now called Red-topped Tower, and finally in Tamsui where Fort Anthonio[14] (part of the Fort San Domingo museum complex) still stands as the best preserved Redoubt (minor fort) of the Dutch East India Company anywhere in the world. The building was later used by the British consulate until the United Kingdom severed ties with the KMT (Chinese Nationalist Party or Kuomintang) regime and its formal relationship with Taiwan.

See also

- History of Taiwan

- Fort Zeelandia

- Taiwanese aborigines: The European period

- Dutch East India Company

- Koxinga

- Kingdom of Tungning

References

- ^ a b Davidson, James M. The Island of Formosa Past and Present. p. 10.

- ^ Davidson, James M. The Island of Formosa Past and Present. p. 11.

- ^ Blussé, Leonard (2000). "The Cave of the Black Spirits". In Blundell, David (ed.). Austronesian Taiwan. California: University of California. ISBN 0-936127-09-0.

- ^ Keliher, Macabe (2003). Out of China or Yu Yonghe's Tales of Formosa: A History of 17th Century Taiwan. p. 32.

- ^ Andrade, Tonio (2005). How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.

- ^ William Campbell (1903). Formosa under the Dutch: Described from Contemporary Records.

- ^ Knapp, Ronald G. (1995) [1980]. China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. p. 14. ISBN 957-638-334-X.

- ^ a b c Roy, Denny (2003). Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-8014-8805-2.

- ^ Gramann, Kristof (1958). Dutch-Asiatic Trade, 1620–1740. The Hague: M. Nijhoff.

- ^ Shepherd, John (1993). Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-0804720663.

- ^ Knapp, Ronald G. (1995) [1980]. China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. p. 18. ISBN 957-638-334-X.

- ^ a b Roy, Denny (2003). Taiwan: A Political History. p. 16.

- ^ a b Shepherd, John Robert (1995). Marriage and Mandatory Abortion Among the Seventeenth Century Siraya. American Ethnological Society Mongraph Series, No. 6. Arlington, Virgina, USA: American Anthropological Association.

- ^ Guo, Elizabeth & Kennedy, Brian. "Tale of Two Towns". News Review. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

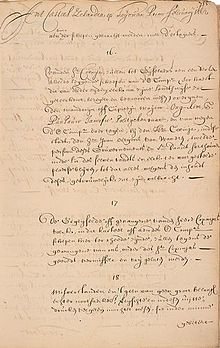

- Valentijn, François (1724–26). Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën (in Dutch). Dordrecht: J. van Braam.

- Wills, John E. Jr. (2005). Pepper, Guns, and Parleys: The Dutch East India Company and China, 1622-1681. Figueroa Press. ISBN 978-1932800081.