Shape of the universe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

The shape of the Universe is an informal name for a subject of investigation within physical cosmology which describes the geometry of the universe including both local geometry and global geometry. It is loosely divided into curvature and topology, even though strictly speaking, it goes beyond both. More formally, the subject in practice investigates which 3-manifold corresponds to the spatial section in comoving coordinates of the 4-dimensional space-time of the Universe.

Introduction

Considerations of the shape of the universe can be split into two parts; the local geometry relates especially to the curvature of the universe at points everywhere, and especially in the observable universe, while the global geometry relates especially to the topology of the universe as a whole — which may or may not be within our ability to measure.

Cosmologists normally work with a given space-like slice of spacetime called the comoving coordinate system. In terms of observation, the section of spacetime that can be observed is the backward light cone (points within the cosmic light horizon, given time to reach a given observer). For related issues, see distance measures (cosmology). The related term Hubble volume can be used to describe either the past light cone or comoving space up to the surface of last scattering. From the point of view of special relativity alone, speaking of "the shape of the universe (at a point in time)" is ontologically naive because of the issue of relativity of simultaneity: you cannot speak of different points in space being "at the same point in time", thus you cannot speak of "the shape of the universe at some point in time". However, the existence of a preferred set of comoving is possible and widely accepted in present-day physical cosmology.

If the observable universe is smaller than the entire universe (in some models it is many orders of magnitude smaller), one cannot determine the global structure by observation: one is limited to a small patch. Conversely, if the observable universe encompasses the entire universe, one can determine the global structure by observation. Further, the universe could be small in some dimension and not in others (like a cylinder): if a small closed loop exists, one would see multiple images of objects in the sky.

Local geometry (spatial curvature)

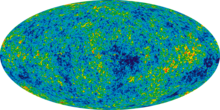

The local geometry is the curvature describing any arbitrary point in the observable universe (averaged on a sufficiently large scale). Many astronomical observations, such as those from supernovae and the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation, show the observable universe to be very close to homogeneous and isotropic and infer it to be accelerating.

FLRW model of the universe

In General Relativity, this is modelled by the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) model. This model, which can be represented by the Friedmann equations, provides a curvature (often referred to as geometry) of the universe based on the mathematics of fluid dynamics, i.e. it models the matter within the universe as a perfect fluid. Although stars and structures of mass can be introduced into an "almost FLRW" model, a strictly FLRW model is used to approximate the local geometry of the observable universe.

Another way of saying this is that if all forms of dark energy are ignored, then the curvature of the universe can be determined by measuring the average density of matter within it, assuming that all matter is evenly distributed (rather than the distortions caused by 'dense' objects such as galaxies).

This assumption is justified by the observations that, while the universe is "weakly" inhomogeneous and anisotropic (see the large-scale structure of the cosmos), it is on average homogeneous and isotropic.

The homogeneous and isotropic universe allows for a spatial geometry with a constant curvature. One aspect of local geometry to emerge from General Relativity and the FLRW model is that the density parameter, Omega (Ω), is related to the curvature of space. Omega is the average density of the universe divided by the critical energy density, i.e. that required for the universe to be flat (zero curvature).

The curvature of space is a mathematical description of whether or not the Pythagorean theorem is valid for spatial coordinates. In the latter case, it provides an alternative formula for expressing local relationships between distances:

- If the curvature is zero, then Ω = 1, and the Pythagorean theorem is correct.

- If Ω > 1, there is positive curvature, and

- if Ω < 1 there is negative curvature;

in either of these cases, the Pythagorean theorem is invalid (but discrepancies are only detectable in triangles whose sides' lengths are of cosmological scale).

If you measure the circumferences of circles of steadily larger diameters and divide the former by the latter, all three geometries give the value π for small enough diameters but the ratio departs from π for larger diameters unless Ω = 1:

- For Ω > 1 (the sphere, see diagram) the ratio falls below π: indeed, a great circle on a sphere has circumference only twice its diameter.

- For Ω < 1 the ratio rises above π.

Astronomical measurements of both matter-energy density of the universe and spacetime intervals using supernova events constrain the spatial curvature to be very close to zero, although they do not constrain its sign. This means that although the local geometries of spacetime are generated by the theory of relativity based on Space-time intervals, we can approximate 3-space by the familiar Euclidean geometry.

Possible local geometries

There are three categories for the possible spatial geometries of constant curvature, depending on the sign of the curvature. If the curvature is exactly zero, then the local geometry is flat; if it is positive, then the local geometry is spherical, and if it is negative then the local geometry is hyperbolic.

The geometry of the universe is usually represented in the system of comoving coordinates, according to which the expansion of the universe can be ignored. Comoving coordinates form a single frame of reference according to which the universe has a static geometry of three spatial dimensions.

Under the assumption that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, the curvature of the observable universe, or the local geometry, is described by one of the three "primitive" geometries (in mathematics these are called the model geometries):

- 3-dimensional Euclidean geometry, generally notated as E3

- 3-dimensional spherical geometry with a small curvature, often notated as S3

- 3-dimensional hyperbolic geometry with a small curvature, often notated as H3

Even if the universe is not exactly spatially flat, the spatial curvature is close enough to zero to place the radius at approximately the horizon of the observable universe or beyond.

Global geometry

Global geometry covers the geometry, in particular the topology, of the whole universe—both the observable universe and beyond. While the local geometry does not determine the global geometry completely, it does limit the possibilities, particularly a geometry of a constant curvature. For this discussion, the universe is taken to be a geodesic manifold, free of topological defects; relaxing either of these complicates the analysis considerably.

In general, local to global theorems in Riemannian geometry relate the local geometry to the global geometry. If the local geometry has constant curvature, the global geometry is very constrained, as described in Thurston geometries.

A global geometry is also called a topology, as a global geometry is a local geometry plus a topology, but this terminology is misleading because a topology does not give a global geometry: for instance, Euclidean 3-space and hyperbolic 3-space have the same topology but different global geometries.

Two strongly overlapping investigations within the study of global geometry are whether the universe:

- Is infinite in extent or, more generally, is a compact space;

- Has a simply or non-simply connected topology.

Detection

It was once thought that the scale of any properties of the topology of a flat spatial geometry is arbitrary. Recent research suggests that the length of the three spatial dimensions may tend to equalise.[1] The length scale of a flat geometry may or may not be directly detectable.

For spherical and hyperbolic spatial geometries, the curvature gives a scale (either by using the radius of curvature or its inverse), a fact noted by Carl Friedrich Gauss in an 1824 letter to Franz Taurinus.[2]

The probability of detection of the topology by direct observation depends on the spatial curvature: a small curvature of the local geometry, with a corresponding radius of curvature greater than the observable horizon, makes the topology difficult or impossible to detect if the curvature is hyperbolic. A spherical geometry with a small curvature (large radius of curvature) does not make detection difficult.

Compactness of the global shape

Formally, the question of whether the universe is infinite or finite is whether it is an unbounded or bounded metric space. An infinite universe (unbounded metric space) means that there are points arbitrarily far apart: for any distance d, there are points that are distance at least d apart. A finite universe is a bounded metric space, where there is some distance d such that all points are within distance d of each other. The smallest such d is called the diameter of the universe, in which case the universe has a well-defined "volume" or "scale."

A compact space is a stronger condition: in the context of Riemannian manifolds, it is equivalent to bounded and geodesically complete. If we assume that the universe is geodesically complete, then boundedness and compactness are equivalent (by the Hopf–Rinow theorem), and they are thus used interchangeably, if completeness is understood.

If the spatial geometry is spherical, the topology is compact. For a flat or a hyperbolic spatial geometry, the topology can be either compact or infinite: for example, Euclidean space is flat and infinite, but the torus is flat and compact.

In cosmological models (geometric 3-manifolds), a compact space is either a spherical geometry, or has infinite fundamental group (and thus is called "multiply connected", or more strictly non-simply connected), by general results on geometric 3-manifolds.

Compact geometries can be visualized by means of closed geodesics: on a sphere, a straight line, when extended far enough in the same direction, will reach the starting point.

Note that on a compact geometry, not every straight line comes back to its starting point. For instance, a line of irrational slope on a torus never returns to its origin. Conversely, a non-compact geometry can have closed geodesics: on a cylinder, which is a non-compact flat geometry, a loop around the cylinder is a closed geodesic.

If the geometry of the universe is not compact, then it is infinite in extent with infinite paths of constant direction that, generally do not return and the space has no definable volume, such as the Euclidean plane.

Open or closed

When cosmologists speak of the universe as being "open" or "closed", they most commonly are referring to whether the curvature is negative or positive. These meanings of open and closed, and the mathematical meanings, give rise to ambiguity because the terms can also refer to a closed manifold i.e. compact without boundary, not to be confused with a closed set. With the former definition, an "open universe" may either be an open manifold, i.e. one that is not compact and without boundary[3], or a closed manifold, while a "closed universe" is necessarily a closed manifold.

In the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) model the universe is considered to be without boundaries, in which case "compact universe" could describe a universe that is a closed manifold.

Flat universe

In a flat universe, all of the local curvature and local geometry is flat. It is generally assumed that it is described by an Euclidean space, however there are some spatial geometries which are flat and bounded in one or more directions.

The alternative two-dimensional spaces with a Euclidean metric are the cylinder and the Möbius strip, which are bounded in one direction but not the other, and the torus and Klein bottle, which are compact.

In three dimensions, there are 10 finite closed flat 3-manifolds, of which 6 are orientable and 4 are non-orientable. The most familiar is the 3-Torus.

Absent dark energy, a flat universe expands forever but at a continually decelerating rate, with expansion asymptotically approaching some fixed rate. With dark energy, the expansion rate of the universe initially slows down, due to the effect of gravity, but eventually increases. The ultimate fate of the universe is the same as that of an open universe.

Spherical universe

A positively curved universe is described by spherical geometry, and can be thought of as a three-dimensional hypersphere, or some other spherical 3-manifold (such as the Poincaré dodecahedral space), all of which are quotients of the 3-sphere.

Analysis of data from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) looks for multiple "back-to-back" images of the distant universe in the cosmic microwave background radiation. It may be possible to observe multiple images of a given object, if the light it emits has had sufficient time to make one or more complete circuits of a bounded universe. Current results and analysis do not rule out a bounded global geometry (i.e. a closed universe), but they do confirm that the spatial curvature is small, just as the spatial curvature of the surface of the Earth is small compared to a horizon of a thousand kilometers or so. If the universe is bounded, this does not imply anything about the sign[citation needed] or zeroness of its curvature.

In a closed universe lacking the repulsive effect of dark energy, gravity eventually stops the expansion of the universe, after which it starts to contract until all matter in the observable universe collapses to a point, a final singularity termed the Big Crunch, by analogy with Big Bang. However, if the universe has a large amount of dark energy (as suggested by recent findings), then the expansion of the universe could continue forever.

Based on analyses of the WMAP data, cosmologists during 2004-2006 focused on the Poincaré dodecahedral space (PDS), but horn topologies (which are hyperbolic) were also deemed compatible with the data.

Hyperbolic universe

A hyperbolic universe is described by hyperbolic geometry, and can be thought of locally as a three-dimensional analog of an infinitely extended saddle shape. There are a great variety of hyperbolic 3-manifolds, and their classification is not completely understood. For hyperbolic local geometry, many of the possible three-dimensional spaces are informally called horn topologies, so called because of the shape of the pseudosphere, a canonical model of hyperbolic geometry.

Proposed models

Various models have been proposed for the global geometry of the universe. In addition to the primitive geometries, these proposals include the:

- Poincaré dodecahedral space, a positively curved space, colloquially described as "soccer ball shaped", as it is the quotient of the 3-sphere by the binary icosahedral group, which is very close to icosahedral symmetry, the symmetry of a soccer ball.

- Picard horn, a negatively curved space, colloquially described as "funnel-shaped", for the horn geometry.

See also

- Theorema Egregium − The "remarkable theorem" discovered by Gauss which showed there is an intrinsic notion of curvature for surfaces. This is used by Riemann to generalize the (intrinsic) notion of curvature to higher dimensional spaces.

- Extra dimensions in String Theory for 6 or 7 extra space-like dimensions all with a compact topology.

- Ekpyrotic universe − a String theory-related model depicting a five-dimensional, membrane-shaped universe; an alternative to the Hot Big Bang Model, whereby the universe is described to have originated when two membranes collided at the fifth dimension.

References

- ^ Roukema, Boudewijn F. (8 Dec 2006). "A weak acceleration effect due to residual gravity in a multiply connected universe". Astronomy and Astrophysics. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Carl F. Gauss, Werke 8, 175-239, cited and translated in John W. Milnor (1982) Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 6(1), p. 10.

Milnor's translation reads:

- "The assumption that the sum of the three angles [of a triangle] is smaller than 180° leads to a geometry which is quite different from our (euclidean) geometry, but which is in itself completely consistent. I have satisfactorily constructed this geometry for myself so that I can solve every problem, except for the determination of one constant, which cannot be ascertained a priori. The larger one chooses this constant, the closer one approximates euclidean geometry. . . . If non-euclidean geometry were the true geometry, and if this constant were comparable to distances which we can measure on earth or in the heavens, then it could be determined a posteriori. Hence I have sometimes in jest expressed the wish that euclidean geometry is not true. For then we would have an absolute a priori unit of measurement."

- ^ Since the universe is assumed connected, we do not need to specify the more technical "an open manifold is one without compact component".

External links

- Oct 2003 − Poincaré dodecahedral model − WMAP statistics model predictions for a spherical local geometry

- Feb 2004 − Poincaré dodecahedral model − 11 degree matched circles

- Universe is Finite, "Soccer Ball"-Shaped, Study Hints. Possible wrap-around dodecahedral shape of the universe

- Hyperbolic universes with a Horned Topology and the CMB Anisotropy

- Classification of possible universes in the Lambda-CDM model.

- Closed hyperbolic universe.