Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland | |

|---|---|

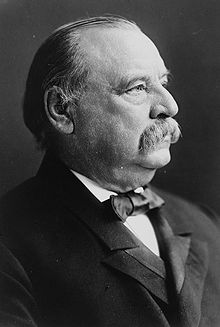

Cleveland in 1903 by Frederick Gutekunst | |

| 24th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897 | |

| Vice President | Adlai E. Stevenson (1893–1897) |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Succeeded by | William McKinley |

| 22nd President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1885 – March 4, 1889 | |

| Vice President | Thomas A. Hendricks (1885, died in office), None (1885–1889) |

| Preceded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Harrison |

| 28th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1883 – January 6, 1885 | |

| Lieutenant | David B. Hill |

| Preceded by | Alonzo B. Cornell |

| Succeeded by | David B. Hill |

| 34th Mayor of Buffalo, New York | |

| In office January 2 – November 20, 1882 | |

| Preceded by | Alexander Brush |

| Succeeded by | Marcus M. Drake |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 18, 1837 Caldwell, New Jersey |

| Died | June 24, 1908 (aged 71) Princeton, New Jersey |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Frances Folsom Cleveland |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837– June 24, 1908) was both the twenty-second and twenty-fourth President of the United States. Cleveland is the only President to serve two non-consecutive terms (1885–1889 and 1893–1897). He was the winner of the popular vote for President three times—in 1884, 1888, and 1892—and was the only Democrat elected to the Presidency in the era of Republican political domination that lasted from 1860 to 1912. Cleveland's admirers praise him for his honesty, independence, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism.[1] As a leader of the Bourbon Democrats, he opposed imperialism, taxes, subsidies and inflationary policies, but as a reformer he also worked against corruption, patronage, and bossism.

Some of Cleveland's actions caused controversy even within his own party. His intervention in the Pullman Strike of 1894 in order to keep the railroads moving angered labor unions, and his support of the gold standard and opposition to free silver alienated the agrarian wing of the Democrats.[2] Furthermore, critics complained that he had little imagination and seemed overwhelmed by the nation's economic disasters—depressions and strikes—in his second term.[2] Even so, his reputation for honesty and good character survived the troubles of his second term. In the words of his biographer, Allan Nevins, "in Grover Cleveland the greatness lies in typical rather than unusual qualities. He had no endowments that thousands of men do not have. He possessed honesty, courage, firmness, independence, and common sense. But he possessed them to a degree other men do not."[3]

Family and early life

Childhood and family history

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born on March 18, 1837 in Caldwell, New Jersey to Richard Falley Cleveland and his wife, Ann Neal.[4] Cleveland's father was a Presbyterian minister, originally from Connecticut.[5] His mother was from Baltimore, the daughter of a bookseller.[6] On his father's side, Cleveland was descended from English ancestors, the first Cleveland having emigrated to Massachusetts from northeastern England in 1635.[7] On his mother's side, Cleveland was descended from Anglo-Irish Protestants and German Quakers from Philadelphia.[8] He was distantly related to the General Moses Cleaveland after whom the city of Cleveland, Ohio, was named.[9]

Cleveland was the fifth of nine children born to Richard and Ann Cleveland, five sons and four daughters.[6] He was named Stephen Grover in honor of the first pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Caldwell, where his father was pastor at the time, but never used the name Stephen in his adult life.[10] In 1841, the Cleveland family moved to Fayetteville, New York, where Cleveland spent much of his childhood.[11] Neighbors would later describe Cleveland as "full of fun and inclined to play pranks",[12] and fond of outdoor sports.[13] In 1850, Cleveland's father took a job in Clinton, New York, and the family relocated there.[14] They moved again in 1853 to Holland Patent, New York, near Utica.[15] Not long after the family arrived in Holland Patent, Cleveland's father died.[15]

Education and moving west

Cleveland's education began in grammar school at the Fayetteville Academy.[16] When the family moved to Clinton, Cleveland was enrolled at the Clinton Liberal Academy.[17] After his father died in 1853, Cleveland left school and helped to support his family.[18] Later that year, Cleveland's brother William was hired as a teacher at the New York Institute for the Blind in New York City, and William obtained a place for Cleveland as an assistant teacher.[18] After teaching for a year, Cleveland returned home to Holland Patent at the end of 1854.[19]

Back in Holland Patent, the seventeen-year-old Cleveland looked for work unsuccessfully.[19] An elder in his church offered to pay for his college education if he would promise to become a minister, but Cleveland declined.[19] Instead, the following spring Cleveland decided to make his way west to the city of Cleveland, Ohio.[19] He stopped first in Buffalo, where his uncle, Lewis W. Allen, lived. Allen dissuaded Cleveland from continuing west, and offered him a job arranging his herdbooks.[20] Allen was an important man in Buffalo, and he introduced his nephew to influential men there, including the partners in the law firm of Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers.[21] Cleveland later took a clerkship with the firm, and was admitted to the bar in 1859.[22]

Early career and the Civil War

After becoming a lawyer, Cleveland worked for the Rogers firm for three years, leaving in 1862 to start his own practice.[24] In January 1863, he accepted an appointment as an assistant district attorney of Erie County.[25] With the American Civil War raging, Congress passed the Conscription Act of 1863, requiring able-bodied men to serve in the army if called upon, or else to hire a substitute.[22] Cleveland chose the latter course, paying George Benninsky, a thirty-two year-old Polish immigrant, $150 to serve in his place.[26] As a lawyer, Cleveland became known for his single-minded concentration and dedication to hard work.[27] In 1866, he defended some of the participants in the Fenian raid of that year, doing so successfully and free of charge.[28] In 1868, Cleveland attracted some attention within his profession for his successful defense of a libel suit against the editor of the Commercial Advertiser, a Buffalo newspaper.[29] During this time, Cleveland lived simply in a boarding house; although his income grew sufficient to support a more lavish lifestyle, Cleveland continued to support his mother and younger sisters.[30] While his personal quarters were austere, Cleveland did enjoy an active social life and enjoyed "the easy-going sociability of hotel-lobbies and saloons."[31]

Political career in New York

Sheriff of Erie County

From his earliest involvement in politics, Cleveland had aligned himself with the Democratic Party.[32] In 1865, he ran for District Attorney, losing narrowly to his friend and roommate, Lyman K. Bass, the Republican nominee.[27] Cleveland then stayed out of politics for a few years, but in 1870, with the help of his friend, Oscar Folsom, he secured the Democratic nomination for sheriff of Erie County.[33] At the age of thirty-three, Cleveland found himself elected sheriff by a 303-vote margin, taking office on January 1, 1871.[34] While this new career took him away from the practice of law, it was rewarding in other ways: the fees were said to yield up to $40,000 over the two-year term.[33] The most well-known incident of his term involved the execution of a murderer, Patrick Morrisey, on September 6, 1872.[35] Cleveland, as sheriff, was responsible for either personally carrying out the execution, or paying a deputy $10 to perform the task.[35] Cleveland had qualms about the hanging, but opted to carry out the duty himself.[35] He hanged another murderer, John Gaffney, on February 14, 1873.[36]

After his term as sheriff ended, Cleveland returned to private practice, opening a law firm with his friends Lyman K. Bass and Wilson S. Bissell.[37] Bass did not spend much time at the firm, being elected to Congress in 1873, but Cleveland and Bissell soon found themselves at the top of Buffalo's legal community.[38] Up to that point, Cleveland's political career had been honorable but unremarkable. As his biographer Allan Nevins wrote "probably no man in the country, on March 4, 1881, had less thought than this limited, simple, sturdy attorney of Buffalo that four years later he would be standing in Washington and taking the oath as President of the United States."[39]

Mayor of Buffalo

In the 1870s, the government of Buffalo had grown increasingly corrupt, with Democratic and Republican political machines cooperating to share the spoils.[40] When, in 1881, the Republicans nominated a slate of particularly disreputable machine politicians, the Democrats saw the opportunity to gain the votes of disaffected Republicans by nominating a more honest candidate.[41] The party leaders approached Cleveland and he agreed to run for mayor, provided that the rest of the ticket was to his liking.[42] When the more notorious politicians were left off the Democratic ticket, Cleveland accepted the nomination.[42] Cleveland was elected mayor with 15,120 votes, as against 11,528 for Milton C. Beebe, his opponent.[43] He took office January 2, 1882.

Cleveland's term as mayor was spent fighting the entrenched interests of the party machines.[44] Among the acts that established his reputation was a veto of the street-cleaning bill passed by the Common Council.[45] The street-cleaning contract was open for bids, and the Council selected the highest bidder, rather than the lowest, because of the political connections of the bidder.[45] While this sort of bi-partisan graft had previously been tolerated in Buffalo, Mayor Cleveland would have none of it, and replied with a stinging veto message: "I regard it as the culmination of a most bare-faced, impudent, and shameless scheme to betray the interests of the people, and to worse than squander the public money".[46] The Council reversed themselves and awarded the contract to the lowest bidder.[47] For this, and several other acts to safeguard the public funds, Cleveland's reputation as an honest politician began to spread beyond Erie County.[48]

Governor of New York

As his reputation grew, state Democratic party officials began to consider Cleveland a possible nominee for governor.[49] Daniel Manning, a party insider who admired Cleveland's record, promoted his candidacy.[50] With a split in the state Republican party, 1882 looked to be a Democratic year and there were several contenders for that party's nomination.[49] The two leading Democratic candidates were Roswell P. Flower and Henry W. Slocum, but their factions deadlocked and the convention could not agree on a nominee.[51] Cleveland, in third place on the first ballot, picked up support in subsequent votes and emerged as the compromise choice.[52] The Republican party remained divided against itself, and in the general election Cleveland emerged the victor, with 535,318 votes to Republican nominee Charles J. Folger's 342,464.[53] Cleveland's margin of victory was, at the time, the largest in a contested New York election, and the Democrats also picked up seats in both houses of the legislature.[54]

Continuing his opposition to unnecessary spending, Cleveland sent the legislature eight vetos in his first two months in office.[55] The first to attract attention was his veto of a bill to reduce the fares on New York City elevated trains to five cents.[56] The bill had broad support because the el trains' owner, Jay Gould, was unpopular and his fare increases were widely denounced.[57] Cleveland saw the bill as unjust—Gould had taken over the railroads when they were failing and had made the system solvent again.[58] Moreover, Cleveland believed that altering Gould's franchise would violate the Contract Clause of the federal Constitution.[58] Despite the initial popularity of the measure, the newspapers praised Cleveland's veto.[58] Theodore Roosevelt, then a member of the Assembly, said that he had initially voted for the bill believing it was wrong, but wishing to punish the unscrupulous railroad barons.[59] After the veto, Roosevelt reversed himself, as did many legislators, and the veto was sustained.[59]

Cleveland's blunt, honest ways won him popular acclaim, but they also gained him the enmity of certain factions of his own party, especially the Tammany Hall organization in New York City.[60] Tammany, under its boss, John Kelly, had not supported Cleveland's nomination as governor, and disliked him all the more when Cleveland openly opposed the re-election of one of their State Senators.[61] Losing Tammany's support was balanced, however, by gaining the support of Theodore Roosevelt and other reform-minded Republicans who helped Cleveland to pass several laws reforming municipal governments.[62]

Election of 1884

Nomination for President

The Republicans convened in Chicago and nominated former Speaker of the House James G. Blaine of Maine for President on the fourth ballot. Blaine's nomination alienated many Republicans who viewed Blaine as ambitious and immoral.[63] Democratic party leaders saw the Republicans' choice as an opportunity to take back the White House for the first time since 1856 if the right candidate could be found.[63]

Among the Democrats, Samuel J. Tilden was the initial front-runner, having been the party's nominee in the contested election of 1876.[64] Tilden, however, was in poor health, and after he declined to be nominated, his supporters shifted to several other contenders.[64] Cleveland was among the leaders in early support, but Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, Allen G. Thurman of Ohio, and Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts also had considerable followings, along with various favorite sons.[64] Each of the other candidates had hindrances to his nomination: Bayard had spoken in favor of secession in 1861, making him unacceptable to Northerners; Butler, conversely, was reviled throughout the South for his actions during the Civil War; Thurman was generally well-liked, but was growing old and infirm and his views on the silver question were uncertain.[65] Cleveland, too, had detractors—Tammany remained opposed to him—but the nature of his enemies made him more friends still.[66] Cleveland led on the first ballot, with 392 votes out of 820.[67] On the second ballot, Tammany threw its support behind Butler, but the rest of the delegates shifted to Cleveland, and he was nominated.[68] Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana was selected as his running mate.[68]

Campaign against Blaine

After Cleveland's nomination, reform-minded Republicans called "Mugwumps" denounced Blaine as corrupt and flocked to Cleveland.[69] The Mugwumps, including such men as Carl Schurz and Henry Ward Beecher, were more concerned with ideals than with party, and hoped that Cleveland would endorse their crusade for civil service reform and efficiency in government.[69] At the same time that the Democrats gained support from the Mugwumps, they lost some to the Greenback-Labor party, led by ex-Democrat Benjamin Butler.[70]

Each candidate's supporters cast aspersions on their opponents. Cleveland's supporters rehashed the old allegations that Blaine had corruptly influenced legislation in favor of the Little Rock & Fort Smith Railroad and the Northern Pacific Railway, later profiting on the sale of bonds he owned in both companies.[71] Although the stories of Blaine's favors to the railroads had made the rounds eight years earlier, this time Blaine's correspondence was discovered, making his earlier denials less plausible.[71] On some of the most damaging correspondence, Blaine had written "Burn this letter," giving Democrats the last line to their rallying cry: "Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine, 'Burn this letter!'"[72]

To counter Cleveland's image of purity, his opponents reported that Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate child while he was a lawyer in Buffalo.[73] The derisive phrase "Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?" rose as an unofficial campaign slogan for those who opposed him.[73] When confronted with the emerging scandal, Cleveland's instructions to his campaign staff were: "Tell the truth."[74] Cleveland admitted to paying child support in 1874 to Maria Crofts Halpin, the woman who claimed he fathered her child named Oscar Folsom Cleveland.[73] Halpin was involved with several men at the time, including Cleveland's friend and law partner, Oscar Folsom, for whom the child was named.[73] Cleveland did not know which man was the father, and is believed to have assumed responsibility because he was the only bachelor among them.[73]

Both candidates believed that the states of New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut would determine the election.[75] In New York, the Tammany Hall, after vacillating, decided that they would gain more from supporting a Democrat they disliked than a Republican who would do nothing for them.[76] Blaine hoped that he would have more support from Irish Americans than Republicans typically did; while the Irish were mainly a Democratic constituency in the 19th century, Blaine's mother was Irish Catholic, and he had been supportive of the Irish National Land League while he was Secretary of State.[77] The Irish, a significant group in three of the swing states, did appear inclined to support Blaine until one of his supporters, Samuel D. Burchard, gave a speech denouncing the Democrats as the party of "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion".[78] The Democrats spread the word of this insult in the days before the election, and Cleveland narrowly won all four of the swings states, including New York by just over one thousand votes.[79] While the popular vote total was close, with Cleveland winning by just one-quarter of a percent, the electoral votes gave Cleveland a majority of 219–182.[79] Following the electoral victory, the "Ma, Ma..." attack phrase gained a classic rejoinder: "Gone to the White House. Ha! Ha! Ha!"

First term as President (1885–1889)

Reform

Soon after taking office, Cleveland was faced with the task of filling all of the government jobs for which the President had the power of appointment. These jobs were typically filled under the spoils system, but Cleveland announced that he would not fire any Republican who was doing his job well, and would not appoint anyone based solely on party service.[80] He also used his appointment powers to reduce the number of federal employees, as many departments had become bloated with political time-servers.[81] Later in his term, as his fellow Democrats chafed at being excluded from the spoils, Cleveland began to replace more of the partisan Republican officeholders with Democrats.[82] While some of his decisions were influenced by party concerns, more of Cleveland's appointments were decided by merit alone than was the case in his predecessors' administrations.[83]

Cleveland reformed other parts of the government, as well. In 1887, he signed the act creating the Interstate Commerce Commission.[84] He and his Secretary of the Navy, William C. Whitney, undertook to modernize the navy and canceled construction contracts that had resulted in inferior ships.[85] Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of western lands they held by government grant.[86] Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q.C. Lamar charged that the rights of way for this land must be returned to the public because the railroads failed to extend their lines according to agreements.[86] The lands were forfeited, resulting in the return of approximately 81,000,000 acres (330,000 km2).[86]

Vetoes

Cleveland faced a Republican Senate and often resorted to using his veto powers.[87] He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for American Civil War veterans, believing that if their pensions requests had already been rejected by the Pensions Bureau, Congress should not attempt to override that decision.[88] When Congress, pressured by the Grand Army of the Republic, passed a bill granting pensions for disabilities not caused by military service, Cleveland vetoed that, too.[89] Cleveland used the veto far more often than any President up to that time.[90] In 1887, Cleveland issued his most well-known veto, that of the Texas Seed Bill.[91] After a drought had ruined crops in several Texas counties, the Congress appropriated $10,000 to purchase seed grain for farmers there.[91] Cleveland vetoed the expenditure. In his veto message, he espoused a theory of limited government: "I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution; and I do not believe that the power and duty of the General Government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadily resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that, though the people support the Government, the Government should not support the people."[92]

Silver

One of the most volatile issues of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone.[93] The issue cut across party lines, with western Republicans and southern Democrats joining together in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the northeast holding firm for the gold standard.[94] Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply.[94]

Cleveland and his Treasury Secretary, Daniel Manning, stood firmly on the side of the gold standard, and tried to reduce the amount of silver that the government was required to coin under the Bland-Allison Act of 1878.[95] This angered Westerners and Southerners, who advocated for cheap money to help their poorer constituents.[96] In reply, one of the foremost silverites, Richard P. Bland, introduced a bill in 1886 that would require the government to coin unlimited amounts of silver, inflating the then-deflating currency.[97] While Bland's bill was defeated, so was a bill the administration favored that would repeal any silver coinage requirement.[97] The result was a retention of the status quo, and a postponement of the resolution of the free silver issue.[98]

Tariffs

| "When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, it is plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice... The public Treasury, which should only exist as a conduit conveying the people's tribute to its legitimate objects of expenditure, becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people's use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country's development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder." |

| Cleveland's third annual message to Congress, December 6, 1887.[99] |

Another contentious financial issue at the time was the protective tariff. While it had not been a central point in his campaign, Cleveland's opinion on the tariff was that of most Democrats: that the tariff ought to be reduced.[100] Republicans generally favored a high tariff to protect American industries.[100] American tariffs had been high since the Civil War, and by the 1880s the tariff brought in so much revenue that the government was running a surplus.[101]

In 1886, a bill to reduce the tariff was narrowly defeated in the House.[102] The tariff issue was emphasized in the Congressional elections that year, and the forces of protectionism increased their numbers in the Congress.[103] Nevertheless, Cleveland continued to advocate tariff reform. As the surplus grew, Cleveland and the reformers called for a tariff for revenue only.[104] His message to Congress in 1887 (quoted at left) pointed out the injustice of taking more money from the people than the government needed to pay for its operating expenses.[105] Republicans, as well as protectionist northern Democrats like Samuel J. Randall, believed that without high tariffs American industries would fail, and continued to fight reformers' efforts.[106] Roger Q. Mills, the chairman of the House Committee on Ways and Means, proposed a bill that would reduce the tariff burden from about 47% to about 40%.[107] After significant exertions by Cleveland and his allies, the bill passed the House.[107] The Republican Senate, however, failed to come to agreement with the Democratic House, and the bill died in the conference committee. Dispute over the tariff would carry over into the 1888 Presidential election.

Foreign policy

Cleveland was a committed non-interventionist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He refused to promote the previous administration's Nicaragua canal treaty, and generally was less of an expansionist in foreign relations.[108] Cleveland's Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard, negotiated with Joseph Chamberlain of the United Kingdom over fishing rights in the waters off Canada, and struck a conciliatory note, despite the opposition of New England's Republican Senators.[109] Cleveland also withdrew from Senate consideration the Berlin Conference treaty which guaranteed an open door for U.S. interests in the Congo.[110]

Marriage

Cleveland entered the White house as a bachelor, but did not remain one for very long. In 1885, the daughter of Cleveland's friend Oscar Folsom visited him in Washington.[111] Folsom's daughter, Frances, was a student at Wells College, and when she returned to school Cleveland received her mother's permission to correspond with her.[111] They were soon engaged to be married.[111] On June 2, 1886, Cleveland married Frances in the Blue Room in the White House.[112] He was the second President to marry while in office, and the only President to have a wedding in the White House.[113] This marriage was unusual because Cleveland was the executor of Oscar Folsom's estate and had supervised Frances' upbringing, but the public did not, in general, take exception to the match.[114] At twenty-one years old, Frances was the youngest First Lady in American history, but the public soon warmed to her beauty and warm personality.[115] The Clevelands had five children: Ruth (1891–1904); Esther (1893–1980); Marion (1895–1977); Richard Folsom (1897–1974); and Francis Grover (1903–1995).

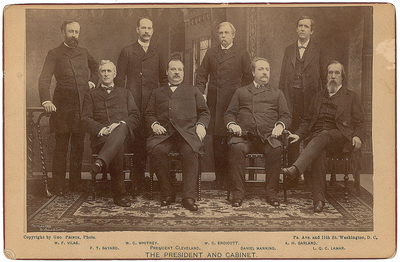

Administration and Cabinet

Front row, left to right: Thomas F. Bayard, Cleveland, Daniel Manning, Lucius Q. C. Lamar

Back row, left to right: William F. Vilas, William C. Whitney, William C. Endicott, Augustus H. Garland

| OFFICE | TERM | |

|---|---|---|

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1885–1889 |

| Vice President | Thomas A. Hendricks | 1885 |

| None | 1885–1889 | |

| Secretary of State | Thomas F. Bayard | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Daniel Manning | 1885–1887 |

| Charles S. Fairchild | 1887–1889 | |

| Secretary of War | William C. Endicott | 1885–1889 |

| Attorney General | Augustus H. Garland | 1885–1889 |

| Postmaster General | William F. Vilas | 1885–1888 |

| Donald M. Dickinson | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | William C. Whitney | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Lucius Q. C. Lamar | 1885–1888 |

| William F. Vilas | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Norman Jay Coleman | 1889 |

Supreme Court appointments

Cleveland successfully appointed two Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. The first, Lucius Q.C. Lamar, was a former Mississippi Senator then serving in Cleveland's Cabinet as Interior Secretary. When William Burnham Woods died, Cleveland nominated Lamar to his seat in late 1887.[116] While Lamar had been well-liked as a Senator, his service under the Confederacy two decades earlier caused many Republicans to vote against him.[116] Lamar's nomination was confirmed by the narrow margin of 32 to 28.[116]

Chief Justice Morrison Waite died a few months later, and Cleveland nominated Melville Fuller to his seat on April 30, 1888.[117] Cleveland had previously offered to nominate Fuller to the Civil Service Commission, but Fuller declined to leave his Chicago law practice.[118] Fuller accepted the Supreme Court nomination, and the Senate Judiciary Committee spent several months examining the little-known nominee.[117] Finding him acceptable, the Senate confirmed the nomination 41 to 20.[117]

Election of 1888 and return to private life

Defeated by Harrison

The debate over tariff reduction continued into the 1888 presidential campaign.[119] The Republicans nominated Benjamin Harrison of Indiana for President and Levi P. Morton of New York for Vice President. Cleveland was easily renominated at the Democratic convention in St. Louis.[120] Vice President Hendricks having died in 1885, the Democrats chose Allen G. Thurman of Ohio to be Cleveland's running mate.[120] The Republicans campaigned heavily on the tariff issue, turning out protectionist voters in the important industrial states of the North.[119] Further, the Democrats in New York were divided over the gubernatorial candidacy of David B. Hill, weakening Cleveland's support in that swing state.[121]

As in 1884, the election focused on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Indiana. Unlike that year, when Cleveland triumphed in all four, in 1888 he won only two, losing his home state of New York by 14,373 votes.[122] More notoriously, the Republicans were victorious in Indiana, largely as the result of fraud.[123] Republican victory in that state, where Cleveland lost by just 2,348 votes, was sufficient to propel Harrison to victory, despite his loss of the nationwide popular vote.[122] Cleveland continued his duties diligently until the end of the term and began to look forward to return to private life.[124]

Private citizen for four years

As Frances Cleveland left the White House, she told a staff member, "Now, Jerry, I want you to take good care of all the furniture and ornaments in the house, for I want to find everything just as it is now, when we come back again." When asked when she would return, she responded, "We are coming back four years from today."[125] In the meantime, the Clevelands moved to New York City where Cleveland took a position with the law firm of Bangs, Stetson, Tracy, and MacVeigh.[126] Cleveland's income with the firm was not high, but neither were his duties especially onerous.[127] While they lived in New York, the Clevelands' first child, Ruth, was born in 1891.[128]

The Harrison administration worked with Congress to pass the McKinley Tariff and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, two policies Cleveland deplored as dangerous to the nation's financial health.[129] At first he refrained from criticizing his successor, but by 1891 Cleveland felt compelled to speak out, addressing his concerns in an open letter to a meeting of reformers in New York.[130] The "silver letter" thrust Cleveland's name back into the spotlight just as the 1892 election was approaching.[131]

Election of 1892

Democratic nomination

Cleveland's stature as an ex-President and recent pronouncements on the monetary issues made him a leading contender for the Democratic nomination.[132] His leading opponent was David B. Hill, who was by that time a Senator for New York.[133] Hill united the anti-Cleveland elements of the Democratic party—silverites, protectionists, and Tammany Hall—but was unable to create a coalition large enough to deny Cleveland the nomination.[133] Despite some desperate maneuvering by Hill, Cleveland was nominated on the first ballot at the convention in Chicago.[134] For Vice President, the Democrats chose to balance the ticket with Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois, a silverite.[135]

Campaign against Harrison

The Republicans renominated President Harrison, making the 1892 election a rematch of the one four years earlier. Unlike the elections of 1884 and 1888, the 1892 election was "the cleanest, quietest, and most creditable in the memory of the post-war generation."[136] The issue of the tariff had worked to the Republicans' advantage in 1888, but the revisions of the past four years had made imported goods so expensive that now many voters shifted to the reform position.[137] Many westerners, traditionally Republican voters, defected to the new Populist Party candidate, James Weaver, who promised free silver, generous veterans' pensions, and an eight-hour work day.[138] Finally, the Tammany Hall Democrats adhered to the national ticket, allowing a united Democratic party to carry New York.[139] The result was a victory for Cleveland by wide margins in both the popular and electoral votes.[140]

Second term as President (1893–1897)

Economic panic and the silver issue

Shortly after Cleveland's second term began, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market, and he soon faced an acute economic depression.[141] The panic was worsened by the acute shortage of gold that resulted from the free coinage of silver, and Cleveland called Congress into session early to deal with the problem.[142] The debate over the coinage was as heated as ever, but the effects of the panic had driven more moderates to support repealing the free coinage provisions of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.[142] Even so, the silverites rallied their following at a convention in Chicago, and the House of Representatives took fifteen weeks of debate before passing the repeal by a considerable margin.[143] In the Senate, the repeal of free coinage was equally contentious, but Cleveland convinced enough Democrats to stand by him that they, along with eastern Republicans, formed a 48–37 majority.[144] With the passage of the repeal, the Treasury's gold reserves were restored to safe levels.[145] At the time the repeal seemed a minor setback to silverites, but it marked the beginning of the end of silver as a basis for American currency.[146]

Tariff reform

Having succeeded in reversing the Harrison administration's silver policy, Cleveland sought next to reverse the effects of the McKinley tariff. What would become the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act was introduced by West Virginian Representative William L. Wilson in December 1893.[147] After lengthy debate, the bill passed the House by a considerable margin.[148] The bill proposed moderate downward revisions in the tariff, especially on raw materials.[149] The shortfall in revenue was to be made up by an income tax of two percent on incomes in excess of $4,000.[149]

The bill was next considered in the Senate, where opposition was stronger.[150] Many Senators, led by Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, wanted more protection for their states' industries than the Wilson bill allowed.[150] Others, such as Morgan and Hill, opposed partly out of a personal enmity to Cleveland.[150] By the time the bill left the Senate, it had more than 600 amendments attached that nullified most of the reforms.[151] The Sugar Trust in particular lobbied for changes that favored it at the expense of the consumer.[152] Cleveland was unhappy with the result, and denounced the revised measure as a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests.[153] Even so, he believed it was an improvement over the McKinley tariff and allowed it to become law without his signature.[154]

Labor unrest

The Panic of 1893 had damaged labor conditions across the United States, and the victory of anti-silver legislation worsened the mood of western laborers.[156] A group of workingmen led by Jacob S. Coxey began to march east toward Washington, D.C. to protest Cleveland's policies.[156] This group, known as Coxey's Army, agitated in favor of a national roads program to give jobs to workingmen, and a weakened currency to help farmers pay their debts.[156] By the time they reached Washington, only a few hundred remained and when they were arrested the next day for walking on the grass of the United States Capitol, the group scattered.[156] Coxey's Army was never a threat to the government, but it showed a growing dissatisfaction in the West with Eastern monetary policies.[157]

The Pullman Strike had a significantly greater impact than Coxey's Army. A strike began against the Pullman Company, and sympathy strikes, encouraged by American Railway Union leader Eugene V. Debs, soon followed.[158] By June 1894, 125,000 railroad workers were on strike, paralyzing the nation's commerce.[159] Because the railroads carried the mail, and because several of the affected lines were in federal receivership, Cleveland believed a federal solution was appropriate.[160] Cleveland obtained an injunction in federal court and when the strikers refused to obey it, he sent in federal troops to Chicago and other rail centers.[161] Leading newspapers of both parties applauded Cleveland's actions, but the use of troops hardened the attitude of organized labor toward his administration.[162]

Foreign policy

| "I suppose that right and justice should determine the path to be followed in treating this subject. If national honesty is to be disregarded and a desire for territorial expansion or dissatisfaction with a form of government not our own ought to regulate our conduct, I have entirely misapprehended the mission and character of our government and the behavior which the conscience of the people demands of their public servants." |

| Cleveland's message to Congress on the Hawaiian question, December 18, 1893.[163] |

In January 1893, a group of Americans living in Hawai'i overthrew Queen Liliuokalani and established a provisional government under Sanford Dole.[164] By February, the Harrison administration had agreed with representatives of the new government on a treaty of annexation and submitted it to the Senate for approval.[164] Five days after taking office, Cleveland withdrew the treaty from the Senate and sent former Congressman James Henderson Blount to Hawaii to investigate the conditions there.[165]

In his first term, Cleveland had supported free trade with Hawai'i and accepted an amendment that gave the United States a coaling and naval station in Pearl Harbor.[110] Now, however, Cleveland agreed with Blount's report, which found the populace to be opposed to annexation.[165] Liliuokalani refused to grant amnesty as a condition of her reinstatement and said she would execute the current government in Honolulu, and Dole's government refused to yield their position.[166] By December 1893, the matter was still unresolved, and Cleveland referred the issue to Congress.[166] In his message to Congress, Cleveland rejected the idea of annexation and encouraged the Congress to continue the American tradition of non-intervention (see excerpt at right).[163] Many in Congress, led by Senator John Tyler Morgan favored annexation, and the report Congress eventually issued favored neither annexation of Hawaii nor the use of American force to restore the Hawaiian monarch.[167]

Closer to home, Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine that did not just simply forbid new European colonies but declared an American interest in any matter within the hemisphere.[168] When Britain and Venezuela disagreed over the boundary between the latter nation and British Guiana, Cleveland and Secretary of State Richard Olney pressured Britain into agreeing to arbitration.[169] A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and issued its award in 1899.[170] The tribunal awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[171] By standing with a Latin American nation against the encroachment of a colonial power, Cleveland improved relations with the United States' southern neighbors, but the cordial manner in which the negotiations were conducted also made for good relations with Britain.[172]

Cancer

In the midst of the fight for repeal of free silver coinage in 1893, Cleveland's doctor found a small ulcerated sore on the left surface of Cleveland's hard palate. Initial biopsies were inconclusive; later the samples were proven to be a malignant cancer. Because of the financial depression of the country, Cleveland decided to have surgery performed in secrecy to avoid further market panic.[173] The surgery occurred on July 1, to give Cleveland time to make a full recovery in time for the upcoming Congressional session.[174]

Under the guise of a vacation cruise, Cleveland and his surgeon, Dr. Joseph Bryant, left for New York. The surgeons operated aboard the yacht Oneida as it sailed off Long Island.[175] The surgery was conducted through the President's mouth, to avoid any scars or other signs of surgery.[176] The team, sedating Cleveland with nitrous oxide and ether, successfully removed parts of his upper left jaw and hard palate.[176] The size of the tumor and the extent of the operation left Cleveland's mouth disfigured.[177] During another surgery, an orthodontist fitted Cleveland with a hard rubber prosthesis that corrected his speech and restored his appearance.[177]

A cover story about the removal of two bad teeth kept the suspicious press placated.[178] Even when a newspaper story appeared giving details of the actual operation, the participating surgeons discounted the severity of what transpired during Cleveland's vacation.[177] In 1917, one of the surgeons present on the Oneida, Dr. William W. Keen, wrote an article detailing the operation.[179]

Administration and Cabinet

Front row, left to right: Daniel S. Lamont, Richard Olney, Cleveland, John G. Carlisle, Judson Harmon

Back row, left to right: David R. Francis, William L. Wilson, Hilary A. Herbert, Julius S. Morton

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

|---|---|---|

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1893–1897 |

| Vice President | Adlai E. Stevenson | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of State | Walter Q. Gresham | 1893–1895 |

| Richard Olney | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | John G. Carlisle | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of War | Daniel S. Lamont | 1893–1897 |

| Attorney General | Richard Olney | 1893–1895 |

| Judson Harmon | 1895–1897 | |

| Postmaster General | Wilson S. Bissell | 1893–1895 |

| William L. Wilson | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Hilary A. Herbert | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of the Interior | M. Hoke Smith | 1893–1896 |

| David R. Francis | 1896–1897 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Julius S. Morton | 1893–1897 |

Supreme Court appointments

Cleveland's trouble with the Senate hindered the success of his nominations to the Supreme Court in his second term. In 1893, after the death of Samuel Blatchford, Cleveland nominated William B. Hornblower to the Court.[180] Hornblower, the head of a New York City law firm, was thought to be a qualified appointee, but his campaign against a New York machine politician had made Senator David B. Hill his enemy.[180] Further, Cleveland had not consulted the Senators before naming his appointee, leaving many who were already opposed to Cleveland on other grounds even more aggrieved.[180] The Senate rejected Hornblower's nomination on January 15, 1894, by a vote of 24 to 30.[180]

Cleveland continued to defy the Senate by next appointing Wheeler Hazard Peckham another New York attorney who had opposed Hill's machine in that state.[181] Hill used all of his influence to block Peckham's confirmation, and on February 16, 1894, the Senate rejected the nomination by a vote of 32 to 41.[181] Reformers urged Cleveland to continue the fight against Hill and to nominate Frederic R. Coudert, but Cleveland acquiesced in an inoffensive choice, that of Senator Edward Douglass White of Louisiana, whose nomination was accepted unanimously.[181] Later, in 1896, another vacancy on the Court led Cleveland to consider Hornblower again, but he declined to be nominated.[182] Instead, Cleveland nominated Rufus Wheeler Peckham, the brother of Wheeler Hazard Peckham, and the Senate confirmed the second Peckham easily.[182]

States admitted to the Union

- Utah– January 4, 1896

Later life and death

As the 1896 election approached, eastern pro-gold-standard Democrats wished Cleveland to run for a third term, but he declined.[183] Instead, the Democratic party turned to a silverite, William Jennings Bryan, for its nominee.[184] Disappointed with the direction of their party, pro-gold Democrats even invited Cleveland to run as a third-party candidate, but he declined this offer, as well.[183] William McKinley, the Republican nominee, triumphed easily over Bryan.[185]

After leaving the White House, Cleveland lived in retirement at his estate, Westland Mansion, in Princeton, New Jersey.[186] For a time he was a trustee of Princeton University, and was one of the majority of trustees who preferred Andrew Fleming West's plans for the Graduate School and undergraduate living over those of Woodrow Wilson, then president of the University.[187] Conservative Democrats hoped to nominate him for another presidential term in 1904, but his age and health forced them to turn to other candidates.[188] Cleveland still made his views known in political matters. In a 1905 article in The Ladies Home Journal, Cleveland weighed in on the women's suffrage movement, writing that "sensible and responsible women do not want to vote. The relative positions to be assumed by men and women in the working out of our civilization were assigned long ago by a higher intelligence."[189]

Cleveland's health had been declining for several years, and in the autumn of 1907 he fell seriously ill.[190] In 1908, he suffered a heart attack and died.[190] His last words were "I have tried so hard to do right."[191] He is buried in the Princeton Cemetery of the Nassau Presbyterian Church.

Honors and memorials

Cleveland's portrait was on the U.S. $1000 bill from 1928 to 1946. He also appeared on a $1000 bill of 1907 and the first few issues of the $20 Federal Reserve Notes from 1914.

Since he was both the 22nd and 24th President, he will be featured on two separate dollar coins to be released in 2012 as part of the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005.

In 2006, Free New York, a nonprofit and nonpartisan research group, began raising funds to purchase the former Fairfield Library in Buffalo, New York and transform it into the Grover Cleveland Presidential Library & Museum.[192]

Notes

- ^ Jeffers, 8–12; Nevins, 4–5

- ^ a b Tugwell, 220–249

- ^ Nevins, 4

- ^ Nevins, 8–10

- ^ Graff, 3–4; Nevins, 8–10

- ^ a b Graff, 3–4

- ^ Nevins, 6

- ^ Nevins, 9

- ^ Graff, 7

- ^ Nevins, 10; Graff, 3

- ^ Nevins, 11; Graff, 8–9

- ^ Nevins, 11

- ^ Jeffers, 17

- ^ Nevins, 17–19

- ^ a b Nevins, 21

- ^ Jeffers, 16–17

- ^ Nevins, 18–19; Jeffers, 19

- ^ a b Nevins, 23–24

- ^ a b c d Nevins, 27

- ^ Nevins, 28–33

- ^ Nevins, 31–36; Graff, 10–11

- ^ a b Graff, 14

- ^ From the Cleveland Family Papers at the New Jersey Archives.

- ^ Graff, 14–15

- ^ Graff, 15; Nevins, 46

- ^ Graff, 14; Nevins, 51–52. Benninsky survived the war.

- ^ a b Nevins, 52–53

- ^ Nevins, 54

- ^ Nevins, 54–55

- ^ Nevins, 55–56

- ^ Nevins, 56

- ^ Nevins, 44–45

- ^ a b Nevins, 58

- ^ Jeffers, 33

- ^ a b c Jeffers, 34; Nevins, 61–62

- ^ "The Execution of John Gaffney". The Buffalonian. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ Jeffers, 36; Nevins, 64

- ^ Nevins, 66–71

- ^ Nevins, 78

- ^ Nevins, 79; Graff, 18–19; Jeffers, 42–45; Welch, 24

- ^ Nevins, 79–80; Graff, 18–19; Welch, 24

- ^ a b Nevins, 80–81

- ^ Nevins, 83

- ^ Graff, 19; Jeffers, 46–50

- ^ a b Nevins, 84–86

- ^ Nevins, 85

- ^ Nevins, 86

- ^ Nevins, 94–95; Jeffers, 50–51

- ^ a b Nevins, 94–99; Graff, 26–27

- ^ Nevins, 95–101

- ^ Graff, 26; Nevins, 101–103

- ^ Nevins, 103–104

- ^ Nevins, 105

- ^ Graff, 28

- ^ Graff, 35

- ^ Graff, 35–36

- ^ Nevins, 114–116

- ^ a b c Nevins, 116–117

- ^ a b Nevins, 117–118

- ^ Nevins, 125–126; Graff, 49–51

- ^ Nevins, 133–138

- ^ Nevins, 138–140

- ^ a b Nevins, 185–186; Jeffers, 96–97

- ^ a b c Nevins, 146–147

- ^ Nevins, 147

- ^ Nevins, 152–153; Graff, 51–53

- ^ Nevins, 153

- ^ a b Nevins, 154; Graff, 53–54

- ^ a b Nevins, 156–159; Graff, 55

- ^ Nevins, 187–188

- ^ a b Nevins, 159–162; Graff, 59–60

- ^ Graff, 59; Jeffers, 111; Nevins, 177, Welch, 34

- ^ a b c d e Nevins, 162–169; Jeffers, 106–111; Graff, 60–65; Welch, 36–39

- ^ Nevins, 163, Graff, 62

- ^ Welch, 33

- ^ Nevins, 170–171

- ^ Nevins, 170

- ^ Nevins, 181–184

- ^ a b Leip, David. "1884 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved January 27, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

- ^ Nevins, 208–211

- ^ Nevins, 214–217

- ^ Graff, 83

- ^ Nevins, 238–241; Welch, 59–60

- ^ Nevins, 354–357; Graff, 85

- ^ Nevins, 217–223; Graff, 77

- ^ a b c Nevins, 223–228

- ^ Graff, 85

- ^ Nevins, 326–328; Graff, 83–84

- ^ Nevins, 300–331; Graff, 83

- ^ See List of United States presidential vetoes

- ^ a b Nevins, 331–332; Graff, 85

- ^ The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland. New York: Cassell Publishing Co. 1892. p. 450.

- ^ Jeffers, 157–158

- ^ a b Nevins, 201–205; Graff, 102–103

- ^ Nevins, 269

- ^ Nevins, 268

- ^ a b Nevins, 273

- ^ Nevins, 277–279

- ^ The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland. New York: Cassell Publishing Co. 1892. pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Nevins, 280–282, Reitano, 46–62

- ^ Nevins, 286–287

- ^ Nevins, 287–288

- ^ Nevins, 290–296; Graff, 87–88

- ^ Nevins, 370–371

- ^ Nevins, 379–381

- ^ Nevins, 383–385

- ^ a b Graff, 88–89

- ^ Nevins, 205; 404–405

- ^ Nevins, 404–413

- ^ a b Zakaria, 80

- ^ a b c Graff, 78

- ^ Graff, 79

- ^ The previous President to marry during his term was John Tyler. Graff, 80

- ^ Jeffers, 170–176; Graff, 78–81; Nevins, 302–308; Welch, 51

- ^ Graff, 80–81

- ^ a b c Nevins, 339

- ^ a b c Nevins, 445–447

- ^ Nevins, 250

- ^ a b Nevins, 418–420

- ^ a b Graff, 90–91

- ^ Nevins, 423–427

- ^ a b Leip, David. "1888 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 18, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ Nevins, 435–439; Jeffers, 220–222; Goldman, 143–144; see also Blocks of Five.

- ^ Nevins, 443–449

- ^ Nevins, 448

- ^ Nevins, 450. The successor to this law firm is Davis Polk & Wardwell.

- ^ Nevins, 450–452

- ^ Nevins, 450; Graff, 99–100

- ^ Graff, 102–105; Nevins, 465–467

- ^ Graff, 104–105; Nevins, 467–468

- ^ Nevins, 470–471

- ^ Nevins, 468–469

- ^ a b Nevins, 470–473

- ^ Nevins, 480–491

- ^ Graff, 105; Nevins, 492–493

- ^ Nevins, 498

- ^ Nevins, 499

- ^ Graff, 106–107; Nevins, 505–506

- ^ Graff, 108

- ^ Leip, David. "1892 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 22, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ^ Graff, 114

- ^ a b Nevins, 526–528

- ^ Nevins, 524–528, 537–540. The vote was 239 to 108.

- ^ Nevins, 541–548

- ^ Graff, 115

- ^ Timberlake, Richard H. (1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History. University of Chicago Press. p. 179. ISBN 0226803848.

- ^ Nevins, 565

- ^ Nevins, 567. The vote was 204 to 140

- ^ a b Nevins, 564–566; Jeffers, 285–287

- ^ a b c Nevins, 567–569

- ^ Nevins, 572–576. The income tax component of the Wilson-Gorman Act was partially ruled unconstitutional in 1895. See Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.

- ^ Nevins, 577–578

- ^ Nevins, 585–587; Jeffers, 288–289

- ^ Nevins, 587–588; Graff, 117

- ^ Nevins, 568

- ^ a b c d Graff, 117–118; Nevins, 603–605

- ^ Graff, 118; Jeffers, 280–281

- ^ Nevins, 611–613

- ^ Nevins, 614

- ^ Nevins, 614–618; Graff, 118–119; Jeffers, 296–297

- ^ Nevins, 619–623; Jeffers, 298–302. See also In re Debs.

- ^ Nevins, 624–628; Jeffers, 304–305; Graff, 120

- ^ a b Nevins, 560

- ^ a b Nevins, 549–552; Graff 121–122

- ^ a b Nevins, 552–554; Graff, 122

- ^ a b Nevins, 558–559

- ^ Graff, 123

- ^ Zakaria, 145–146

- ^ Graff, 123–125; Nevins, 633–642

- ^ Graff, 125

- ^ Nevins, 647

- ^ Nevins, 550, 647–648

- ^ Nevins, 528–529; Graff, 115–116

- ^ Nevins, 531–533

- ^ Nevins, 529

- ^ a b Nevins, 530–531

- ^ a b c Nevins, 532–533

- ^ Nevins, 533; Graff, 116

- ^ Keen, William W. (1917). The Surgical Operations on President Cleveland in 1893. G. W. Jacobs & Co. The lump was preserved and is on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

- ^ a b c d Nevins, 569–570

- ^ a b c Nevins, 570–571

- ^ a b Nevins, 572

- ^ a b Graff, 128–129

- ^ Nevins, 684–693

- ^ Leip, David. "1896 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ^ Graff, 131–133; Nevins, 730–735

- ^ Graff, p. 131; Alexander Leitch, A Princeton Companion, Princeton Univ Press, 1978, " Grover Cleveland"

- ^ Graff, 134

- ^ Ladies Home Journal 22, (October 1905), 7–8

- ^ a b Graff, 135–136; Nevins, 762–764

- ^ Jeffers, 340; Graff, 135. Nevins makes no mention of these last words.

- ^ "Grover Cleveland Library". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

References

Sources

- Graff, Henry F. Grover Cleveland (2002). ISBN 0805069232.

- Jeffers, H. Paul, An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland, HarperCollins 2002, New York. ISBN 038097746X.

- Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (1932) Pulitzer Prize-winning biography. ASIN B000PUX6KQ.

- Reitano, Joanne R. The Tariff Question in the Gilded Age: The Great Debate of 1888 (1994). ISBN 0271010355.

- Tugwell, Rexford Guy, Grover Cleveland: A Biography of the President Whose Uncompromising Honesty and Integrity Failed America in a Time of Crisis. Macmillan Co., 1968. ISBN 0026203308.

- Welch, Richard E. Jr. The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (1988) ISBN 0700603557

- Zakaria, Fareed From Wealth to Power (1999) Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691010358.

Further reading

- Bard, Mitchell. "Ideology and Depression Politics I: Grover Cleveland (1893–1897)" Presidential Studies Quarterly 1985 15(1): 77–88. ISSN 0360-4918

- Beito, David T. and Beito, Linda Royster,"Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900,"Independent Review 4 (Spring 2000), 555–75.

- Blodgett, Geoffrey. "Ethno-cultural Realities in Presidential Patronage: Grover Cleveland's Choices" New York History 2000 81(2): 189–210. ISSN 0146–437X

- Blodgett, Geoffrey. "The Emergence of Grover Cleveland: a Fresh Appraisal" New York History 1992 73(2): 132–168. ISSN 0146–437X

- Cleveland, Grover. The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland (1892) online edition

- Cleveland, Grover. Presidential Problems. (1904) online edition

- Dewey, Davis R. National Problems: 1880–1897 (1907), online edition

- Doenecke, Justus. "Grover Cleveland and the Enforcement of the Civil Service Act" Hayes Historical Journal 1984 4(3): 44–58. ISSN 0364–5924

- Faulkner, Harold U. Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890–1900 (1959), online edition

- Ford, Henry Jones. The Cleveland Era: A Chronicle of the New Order in Politics (1921), short overview online

- Goldman, Ralph Morris The National Party Chairmen and Committees: Factionalism at the Top (1990). ISBN 0873326369.

- Hoffman, Karen S. "'Going Public' in the Nineteenth Century: Grover Cleveland's Repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act" Rhetoric & Public Affairs 2002 5(1): 57–77. ISSN 1094–8392

- McElroy, Robert. Grover Cleveland, the Man and the Statesman: An Authorized Biography (1923) online edition

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896 (1969).

- Nevins, Allan ed. Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908 (1934)

- Sturgis, Amy H. ed. Presidents from Hayes through McKinley, 1877–1901: Debating the Issues in Pro and Con Primary Documents (2003) online edition

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren. Rum, Romanism & Rebellion: The Making of a President, 1884 (2000) campaign techniques and issues online edition

- William L. Wilson; The Cabinet Diary of William L. Wilson, 1896–1897 1957

- National Democratic Committee (1896). Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party.

- Wilson, Woodrow, Mr. Cleveland as President Atlantic Monthly (March 1897): pp. 289–301 online.

External links

- Extensive essay on Grover Cleveland and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- White House website biography of Grover Cleveland

- Works by Grover Cleveland at Project Gutenberg

- Audio clips of Cleveland's speeches

- A picture of Cleveland's Grave Marker in Princeton Cemetery

Template:Persondata {{subst:#if:Cleveland, Grover|}} [[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1837}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1908}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1837 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1908}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1908 deaths

- American Presbyterians

- Americans of English descent

- German-Americans

- Americans of Scots-Irish descent

- New York sheriffs

- Deaths by myocardial infarction

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- United States presidential candidates, 1884

- United States presidential candidates, 1888

- United States presidential candidates, 1892

- Governors of New York

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Mayors of Buffalo, New York

- New York lawyers

- Sex scandal figures

- People from Buffalo, New York

- People from Essex County, New Jersey

- People from Onondaga County, New York

- Presidents of the United States