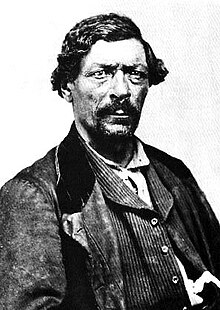

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

| Template:Wikify is deprecated. Please use a more specific cleanup template as listed in the documentation. |

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (February 11, 1805 – May 16, 1866) was an American explorer who is best known for traveling across North America as an infant with his mother Sacagawea as part of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was the son of Sacagawea and her French-Canadian husband, trapper and interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau. Expedition co-leader William Clark nicknamed the boy Pomp or Pompy.

Charbonneau's image can be found on the Sacagawea dollar coin. He is the only child ever depicted on United States currency. Pompeys Pillar on the Yellowstone River in Montana and the community of Charbonneau, Oregon[1] are named for him.

Childhood

Charbonneau was born at Fort Mandan in North Dakota, the encampment at which the Lewis and Clark Expedition wintered in 1804-1805. His father, French-Canadian trapper Toussaint Charbonneau, had been hired by the expedition as an interpreter. Captains Lewis and Clark agreed to bring along his then-pregnant Native American wife Sacagawea when they learned she was of the Shoshone people, as they knew they would need to negotiate with the Shoshone for horses and guides at the headwaters of the Missouri River. Meriwether Lewis noted the boy's birth in his journal:

The party that were ordered last evening set out early this morning. the weather was fair and could wind N. W. about five oclock this evening one of the wives of Charbono was delivered of a fine boy. it is worthy of remark that this was the first child which this woman had boarn and as is common in such cases her labour was tedious and the pain violent; Mr. Jessome informed me that he had freequently administered a small portion of the rattle of the rattle-snake, which he assured me had never failed to produce the desired effect, that of hastening the birth of the child; having the rattle of a snake by me I gave it to him and he administered two rings of it to the woman broken in small pieces with the fingers and added to a small quantity of water. Whether this medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine, but I was informed that she had not taken it more than ten minutes before she brought forth perhaps this remedy may be worthy of future experiments, but I must confess that I want faith as to it's [sic] efficacy.— [2]

Charbonneau traveled from North Dakota to the Pacific Ocean and back as an infant, carried along in the expedition's boats or upon his mother's back. His presence is often credited with reassuring the native tribes the expedition encountered, as it is said they believed that no war party would travel with a woman and child.

In April 1807, two years after the expedition, the Charbonneau family moved to St. Louis, at Clark's invitation. Toussaint Charbonneau and Sacagawea departed for the Mandan villages in April 1809 and left Jean Baptiste behind. In November 1809 the parents returned to St. Louis to try farming, but left again in April 1811. Jean Baptiste continued to reside with Clark.

Clark's two-story home, built in 1818, was spectacular because it contained a brilliantly illuminated museum 100 feet long by 30 feet wide. Its walls were decorated with national flags and lifesize portraits of George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette, Indian artifacts and mounted animal heads. Upon visiting the museum, Henry Schoolcraft, a geologist and ethnographer, wrote, "Clark evinces a philosophical taste in the preservation of many subjects of natural history. We believe this is the only collection of specimens of art and nature west of Cincinnati, which partakes of the character of a museum, or cabinet of natural history."[3] Presumably Charbonneau spent time learning from the vast collection.[citation needed]

Clark paid for a more formal education for Charbonneau, at St. Louis University High School, taught by Baptist reverends John Peck and James Welch. Their classroom was located in the storehouse of another of Clark's friends, trader Joseph Robidoux, and the expense was considerable for the time. Brothers James and George Kennerly paid for Charbonneau's supplies for 1820 and were reimbursed by Clark.

- January 22, 1820: payment to J. E. Welch for two quarters tuition of J. B. Charbonneau, a half Indian boy, and firewood and ink. Amount = $16.37

- April 1, 1820: to J. & G. H. Kennerly for one Roman History for Charbonneau, a half Indian, $1.50; one pair of shoes, $2.24; two pairs of socks, $1.50; two squires of paper and quills, $1.50; 1 [William] Scott's Lesson[4], $1.50; 1 dictionary, $1.50; 1 hat, $4.00; four yards of cloth, $10.00; one ciphering book, $1., one slate and pencils, $.62.

- April 11, 1820: to J. E. Welch for one quarter’s tuition, including fuel and ink. Amount = $8.37.

- June 30, 1820: to Louis Tesson Honore for board, lodging and washing. Amount = $45.00.

- October 1, 1820: to L. T. Honore for lodging, boarding, and washing from 1 July to 30th September at $15.00 per month. Amount = $45.00

- March 31, 1822: to Louis Tesson Honore for boarding, lodging and washing of J. B. Charbonneau, a half Indian.[5]

In June 1820, Charbonneau lived in St. Ferdinand Township near his father's 320 acres of land. He lived with Louis Tesson Honoré, a Clark family friend and member of his church, Christ Episcopal,[6] which the general helped organize in 1819.

Adult life

On June 21, 1823, at age eighteen, Charbonneau met Duke Friedrich Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg, the nephew of King Freidrich I Wilhelm Karl of Württemberg.[7] Charbonneau was working at a Kaw Indian trading post on the Kansas River near present-day Kansas City, Kansas. Wilhelm was traveling in America on a natural history expedition to the northern plains under the guidance of Toussaint Charbonneau. On October 9, 1823, he invited the younger Charbonneau to return to Europe with him, which was agreed upon. The two men set sail on the Smyrna from St. Louis in December 1823. Jean Baptiste lived there for nearly six years and learned German and Spanish. He already spoke French, the dominant language of St. Louis, which enabled conversation with the Duke.[8] According to Wilhelm, Charbonneau was "…a companion on all my travels over Europe and northern Africa until 1829."[9]

In November 1829, Charbonneau returned to St. Louis, where he was hired by Joseph Robidoux as a skin trapper for the American Fur Company in Idaho and Utah.[10][11] He attended the 1832 Pierre's Hole rendezvous while working for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, and fought in the bloodiest non-military battle preceding the Plains Indian wars that began in 1854.[12] From 1833-1849 he worked in the fur trade in the Rocky Mountain Trapping System[13] with other mountain men such as Jim Bridger, James Beckwourth and Joe Meek.[14]

From 1840-1842 he worked from Fort Saint Vrain floating bison hides and tongues 2,000 miles down the South Platte River to St. Louis. On one of the voyages he camped with Captain John C. Frémont on a cartographic expedition. In 1843, he guided William Drummond Stewart on a lavish hunting expedition.[15] Seeking employment again, in 1844 he went to Bent's Fort in Colorado to be chief hunter and trader with southern plains Indians. A traveler who met him, William Boggs, wrote that Charbonneau "…wore his hair long, [and] was…very high strung…" Moreover, "…it was said Charbenau (sic) was the best man on foot on the plains or in the Rocky Mountains." [16]

In October 1846, Charbonneau, Antoine Leroux and Pauline Weaver were hired as scouts by General Stephen W. Kearny. Charbonneau’s experience with military marches, such as with James William Abert [17] in August, 1845, along the Canadian River and his fluency in Indian languages qualified him for the position. Kearny directed him to join Colonel Philip St. George Cooke and Lieutenant William H. Emory on an arduous march from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to San Diego, California, a distance of 1,100 miles. Their mission was to guide 20 huge Murphy supply wagons to California for the military.[18] A Mormon contingent of 339 men accompanied U.S. cavalry on the uncharted trail. The marchers became known as the Mormon Battalion. A memorial to the battalion stands at the San Pedro River, one mile north of the U.S./Mexico border near Palominas, Arizona. Cooke noted that from November 16, 1846, to January 21, 1847, Charbonneau assisted 29 times on the march.[19] Although only eight wagons reached Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, four miles from today’s Oceanside, California, the expedition was a success.

Cooke wrote, "History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry."[20] Known as the Gila Trail, the wagon road was used by settlers, miners, stagecoaches of the Butterfield Stage line and cattlemen driving longhorns to feed the gold camps. Parts of the route became the Southern Pacific Railroad and U.S. Route 66. In February 1848, knowledge gained about the region helped assemble the basis of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which established the United States-Mexico border in December 1853.[21]

In November 1847, Charbonneau accepted an appointment from Colonel John D. Stevenson as alcalde at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia. This position made him the only civilian authority – sheriff, lawyer and magistrate – in a post-war region covering about 225 square miles. From 1834-1850, the lands were owned by rancheros through mostly illegal land-grants. Agricultural work was done by local Indians, mainly Luiseño. Many functioned in servitude and some were paid only with liquor. Consequently, in November, 1847, Colonel Richard Barnes Mason, the territorial governer, ordered Charbonneau to force the sale of a large ranch owned by powerful rancher Jose Antonio Pico. Then on January 1, 1848, Mason banned the sale of liquor to Indians. These ordinances attacked the very foundation of ranchero existence and would make way for U.S. civilian control during post-war occupation. [22] Assisted by Captain J. D. Hunter and after negotiating with Pico to accede, it was clear that local resistance would make enforcing Mason's orders difficult. Consequently, Charbonneau resigned his post in August 1848, and was soon followed by Hunter. California statehood on September 9, 1850, ended the post-war difficulties.

On May 4, 1848, Charbonneau had a daughter, Maria Cantarina Charguana, with Margarita Sobin, a Luiseño woman. Sobin, 23 at the time, traveled to Mission San Fernando Rey de España near Los Angeles for the infant's baptism. It was performed on May 28, 1848, by Father Blas Ordaz as entry #1884. California mission databases do not reveal further information on Charbonneau’s daughter. Margarita Sobin married Gregory Trujillo, some of whose descendants are members of the La Jolla band of Mission Indians.[23]

In September 1848, Charbonneau arrived in Placer County, California, at the American River near what is now Auburn. Arriving early in what became known as the California Gold Rush, he joined only a handful of prospectors. Panning was not done during the hard Sierra Nevada winter or spring runoff, so in June 1849, he joined three others, including Jim Beckwourth, at a camp on Buckner's Bar to mine the river at the Big Crevice. This claim "…was shallow and paid well."[24] Charbonneau lived at a site known as Secret Ravine, one of 12 ravines around Auburn and was a successful miner who was able to stay in the area for nearly sixteen years.

His success was based on being able to afford the mining region's highly-inflated cost of living. For example, at a time when a good wage in the West was $30 per month, it cost $8-16 per day to live in Auburn.[25] Transiency was high but Charbonneau remained in 1861, working as the hotel manager at the Orleans Hotel.[26] By 1858 many miners had left the California fields for other gold rushes. In 1866, he departed for other opportunities at age 61. He most likely headed for Montana to prospect for gold, although other sites such as at Silver City and DeLamar in Idaho Territory were much closer.[27]

Death

Charbonneau died on May, 16, 1866. A death notice was sent by an unknown person, likely one of two fellow travelers on the journey east, to the Owyhee Avalanche newspaper[28]. This is the first documented evidence of his death. [29]

In April, 1866, Charbonneau left Auburn for an unknown purpose. Before leaving he visited the Placer Herald newspaper and left an editor with the belief that "...he was about [his purpose was] returning to familiar scenes."[30] Some of those "familiar scenes" were places he had lived in and worked as a mountain man east of the Great Basin. His destination also may have been the Owyhee Mountains, where rich placer deposits were discovered in May 1863. Or perhaps he sought to reach lawless Alder Gulch near Virginia City, Montana, because it had produced $31,000,000 in gold by late 1865. Other possible destinations were the Bannack, Montana, gold strikes or—as noted above—the mines at Silver City (formerly Ruby City), Delamar or Boonville [31]

His route and travel method likely took him on a stagecoach over Donner Summit and east along the well-traveled Humboldt River Trail to Winnemucca, Nevada, then north to army Camp McDermitt near the Idaho border.[32] Passing the camp in rugged terrain, the men reached the Owyhee River crossing at present-day Rome, Oregon, where an accident occurred as Charbonneau went into the river.

The accident's cause is unknown, but there are several possibilities. He may been on a stagecoach operated by the Boise-Silver City-Winnemucca stage company that began its route in 1866 out of Camp McDermitt and in crossing the river, the coach sank.[33] Or he may have been on horseback and fallen off the river bank or slipped out of the saddle while crossing. The Owyhee River in snowmelt may have turned into whitewater. Other possibilities are he simply got injured on the land journey or inhaled alkali dust or fell ill from drinking contaminated water.[34]

The Owyhee Avalanche death notice stated he died of pneumonia. The Placer Herald obituary writer opined that he succumbed to the infamous "Mountain Fever", which described many illnesses in the West. Whatever the cause, he was taken to Inskip Station in Danner, Oregon, built in 1865, about 33 miles from the river, west of Jordan Valley, Oregon. It is now a ghost town. The former stage coach, mail stop and general store served travelers to Oregon and the California gold fields. It had its own well, and Charbonneau may have deteriorated from drinking the water. [35] After his death, he was carried one-quarter mile north and interred at 42.9518°N 117.339°W, near structural remains, including the Anderson General Store which is intact and appears to be in 1940s condition.

His grave site, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on one acre of land, was donated to Malheur County, Oregon, by the owners of the 6,000-acre Ruby Ranch. The site includes three historical markers. A dedication in 1971 saw a marker placed by the Malheur County Daughters of the American Revolution. A second marker erected in 1973 was arranged by the Oregon Historical Society. The marker reads:

Oregon History

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

1805–1866

This site marks the final resting place of the youngest member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Born to Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau at Fort Mandan (North Dakota), on February 11, 1805, Baptiste and his mother symbolized the peaceful nature of the "Corps of Discovery." Educated by Captain William Clark at St. Louis, Baptiste at 18 traveled to Europe where he spent six years becoming fluent in English, German, French and Spanish. Returning to American in 1829, he ranged the far west for nearly four decades as mountain man, guide, interpreter, magistrate, and forty-niner. In 1866, he left the California gold fields for a new strike in Montana, contracted pneumonia enroute, reached "Inskips Ranche" here, and died on May 16, 1866.

A third dedication was made by Lehmi-Shoshone Family Descendants in 2000 because Charbonneau was the son of Sacagawea, a Northern Shoshone who lived in the Lemhi Valley.

A final site and memorial stands at Fort Washakie, Wyoming, on the Shoshone Wind River Indian Reservation. Proponents of his burial being there argue that Sacagawea also died at the same location on April 9, 1884, based on the work of Dr. Charles Eastman, and assert that Charbonneau lies next to her. Two headstones exist at the site. However, none of the Indians interviewed by Dr. Eastman made reference to Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Eastman's research was done in 1924-25 through oral history and Shoshone language interpretation, although as a Santee Sioux, he may not have spoken the Shoshone language. Oral history methodology is superseded by documentary evidence.

Four 19th-century documents—including a statement made by William Clark after the 1805-1807 Lewis and Clark expedition that "Secarjawea was dead"[36]—establish her date of death as December 20, 1812, of a "putrid fever" at Fort Manuel Lisa on the Missouri River.[37]

See also

References

- ^ McArthur (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (Seventh Edition ed.). Portland, Oregon,: Oregon Historical Society Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-87595-277-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|irst=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Journals of Lewis and Clark: February 11, 1805

- ^ Henry R. Schoolcraft, Travels in the Central portions of the Mississippi Valley (New York: J. and J. Harper, 1825), p. 294.

- ^ Editor's[who?] note: Scott's Lesson textbook formally dealt with elocution, language and speaking

- ^ U. S. Department of the Interior. “Abstract of Expenditures by Captain W. Clark as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, 1822.” American State Papers, vol. 2. (1834) p. 289.

- ^ Ritter, Michael; (2005). Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, Man of Two Worlds. Charleston: Booksurge. p.67. ISBN 1-59457-868-0

- ^ Source: Brigitte Gastel Lloyd and Paul Theroff, January 18, 2002

- ^ Ritter, p.71.

- ^ Ritter, p.75

- ^ Ritter, p.84

- ^ Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series: Jean Baptiste CharbonneauPDF (23.6 KB)

- ^ Ritter, p. 88

- ^ Wishart, David J. The Fur Trade of the American West, 1807-1840, A Geographical Synthesis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979) pp. 125-27

- ^ United States National Park Service: The Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery: Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

- ^ Victor, Frances ed. The River of the West: Life and Adventure in the Rocky Mountains and Oregon. (Hartford: Bliss and Co., 1870) p. 474

- ^ Hafen LeRoy, "The W.M. Boggs Manuscript About Bent's Fort, Kit Carson, the Far West and Life Among the Indians," The Colorado Magazine 7 (March, 1930): pp. 45-69

- ^ Ritter, p. 128

- ^ Ritter, p. 136

- ^ Ritter, p. 150

- ^ Bieber, Ralph, ed. Exploring Southwestern Trails, 1846-1854. (Glendale: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1938) p. 104

- ^ Ritter, p. 151

- ^ Ritter, p. 161.

- ^ First Book of Baptisms May 28, 1848, entry #1884, Plaza Church, Los Angeles, California

- ^ Angel, Myron and Fairchilds, M. D. History of Placer County. (Oakland: Thompson and West, 1882.) p. 229.

- ^ Ritter, p. 176

- ^ Eighth Decennial Census, 1860

- ^ Ritter, p. 190

- ^ Owyhee Avalanche, Ruby City, Idaho Territory, June 2, 1866

- ^ Ritter, p. 201

- ^ Obituary, Placer Herald, July 7, 1866]

- ^ Waldemar Lindgren, Report on Florida Mountain, Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series, 1899

- ^ Ritter, p. 197

- ^ Ritter, p. 198

- ^ Ritter, p. 199

- ^ Ritter, p. 200

- ^ Ottoson, Dennis R. "Toussaint Charbonneau, A Most Durable Man." South Dakota History 6 (Spring, 1976) p. 152

- ^ Luttig, John. Journal of a Fur Trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri, 1812-13. ed Stella Drumm. New York: Argosy-Antiquarian Ltd., 1964

Further reading

- Colby, Susan (2005). Sacagawea's Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste (Pomp) Charbonneau. Spokane: Arthur H. Clarke.

- Kartunnen, Frances (1994). Between Worlds: Interpreters, Guides, and Survivors. Rutgers: Rutgers University Press.

- Moulton, Gary, ed (2003). The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Sargent, Colin (2009). Museum of Human Beings. Ithaca: McBooks.

- Articles needing cleanup from December 2009

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from December 2009

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from December 2009

- 1805 births

- 1866 deaths

- French-Canadian Americans

- People of the California Gold Rush

- People of the American Old West

- Lewis and Clark Expedition people

- Malheur County, Oregon

- Mountain men

- American people of Native American descent

- Burials in Oregon

- Infectious disease deaths in Oregon

- Deaths from pneumonia