Genre

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Sanguination (talk | contribs) 14 years ago. (Update timer) |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (February 2010) |

Genre (pronounced /ˈʒɑːnrə/, also /ˈdʒɑːnrə/; from French, genre /ʒɑ̃ʀ/, "kind" or "sort", from Latin: genus (stem gener-), Greek: genos, γένος) is a loose set of criteria for categorization of literature and speech, as well as many other forms of art or culture. Genres are formed by conventions that change over time as new genres are invented and the use of old ones is discontinued. Often, works fit into multiple genres by way of borrowing and recombining these conventions.

While the scope of the word "genre" is commonly confined to art and culture, it also defines individuals' interactions with and within their environments.

History

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. |

The concept of genre originates with the classification systems founded by Aristotle and Plato. Plato divided literature into the the three classic genres accepted in Ancient Greece: poetry, drama, and prose. Poetry is subdivided into epic, lyric, and drama. The divisions set by Aristotle and Plato were adhered to in literary theory for hundreds of years.

Classical and Romantic genre theory

The earliest recorded systems of genre in Western history can be traced back to Plato and Aristotle.

Gérard Genette, in the Architext, describes Plato as creating three imitational genres (imitation referring to the ability to mimic the natural world [see mimesis], distinguished by mode of imitation rather than content: dramatic dialogue (the drama), pure narrative (the dithyramb), and a mixture of the two (the epic). Lyric poetry was excluded by Plato as a non-mimetic mode. Genette then goes on to state that Aristotle revised Plato's system by first eliminating the pure narrative as a viable mode, then distinguishing by two additional criteria: the object to be imitated (objects could be either superior or inferior) and the medium of presentation (Ex: in words, in gestures, or in verse). Essentially, the three categories of mode, object, and medium can be visualized along an XYZ axis. Excluding the criteria of medium, Aristotle's system distinguished four types of classical genres: tragedy (superior-dramatic dialogue), epic (superior-mixed narrative), comedy (inferior-dramatic dialogue), and parody (inferior-mixed narrative). Genette continues by explaining the integration of lyric poetry into the classical system, replacing the now removed pure narrative mode. Lyric poetry, once considered non-mimetic, was deemed to imitate feelings, becoming the third "Architext" (Gennette coins the term) of a new long enduring tripartite system: lyrical, epical (mixed narrative), and dramatic (dialogue). This new system, which came to "dominate all the literary theory of German romanticism (and therefore well beyond)…" (Genette 38), has seen numerous attempts at expansion or revision. Simple attempts include Friedrich Schlegel's triad of subjective form (lyric), objective form (dramatic), and subjective-objective form (epic). However, more ambitious efforts to expand the tripartite system resulted in new taxonomic systems of increasing complexity. Gennette reflects upon these various systems, comparing them to the original tripartite arrangement: "its structure is somewhat superior to (meaning, or course, more effective than) most of those that have come after, fundamentally flawed as they are by their inclusive and hierarchical taxonomy, which each time immediately brings the whole game to a standstill and produces an impasse" (Genette 74).

Contemporary genre theory and theorists

In 1968, Lloyd Bitzer claimed that discourse is determined by rhetorical situations in an article called, "The Rhetorical Situation". He looks to understand the nature behind the context that determines discourse. Bitzer states, "it is the situation which calls discourse into existence" (Bitzer 2). He expresses the imperative nature of the situation in creating discourse, because discourse only comes into being as a response to a particular situation. Discourse varies depending upon the meaning-context that is created due to the situation, and because of this, it is "embedded in the situation" (Bitzer 4). Bitzer describes rhetorical situations as requiring three components of exigence, audience, and constraints. Bitzer highlights six characteristics needed from a rhetorical situation that are detrimental to creating discourse. The characteristics are as follows, a situation calls a rhetor to create discourse, it invites a response to fit the situation, the response meets the necessary requirements of the situation, the exigence which creates the discourse is located in reality, rhetorical situations exhibit simple or complex structures, rhetorical situations after coming into creation either decline or persist. Bitzer's main argument is the concept that rhetoric is used to "effect valuable changes in reality" (Bitzer 14).

In 1984, Carolyn Miller examined genre in terms of rhetorical situations. She claimed that "situations are social constructs that are the result, not of 'perception,' but of 'definition,'" (Miller 156), or that we essentially define our situations. Miller seems to build from Bitzer's argument regarding what makes something rhetorical, which is the ability of change to occur. Opposite of Bitzer's predestined and limited view of the creation of genres, Miller believes genres are created through social constructs. She agrees with Bitzer, in that past responses can indicate what is appropriate as a current response, but Miller holds that, rhetorically, genre should be "centered not on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish" (Miller 151). Since her view focuses on action, it cannot ignore that humans depend on the "context of the situation" as well as "motives" that drive them to this action (152). Essentially, "we create recurrence," or similar responses, through our "construal" of types (Miller 157). Miller defines "types" as "recognition of relevant similarities" (Miller 156-7). Types come about only after we have attempted to interpret the situation by way of social context, which causes us to stick to "tradition" (Miller 152). Miller does not want to deem recurrence as a constraint, but rather she views it as insight into the "human condition" (Miller 156). The way to bring about a new "type," (Miller 157) though, is to allow for past routines to evolve into new routines, thereby still maintaining a cycle that is always open for change. Either way, Miller's view is in accordance with the fact that as humans, we are creatures of habit that tightly hold on to a certain "stock of knowledge" (Miller 157). However, change is considered innovation and by creating new "types" (Miller 157) we can still keep "tradition" (Miller 152) and innovation at the same time.

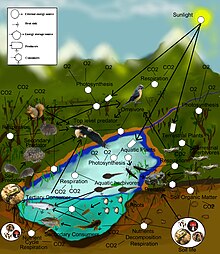

In 2001, Anis Bawarshi's "Ecology of Genre" argues for the teaching of genre as an ecosystem. He compares to an ecosystem in a sense that writing recreates genres as well as reacting to them. The genre itself serves as an ecosystem, defining our interpretation and creation of genre. The idea of a Doctor's office as an ecosystem demonstrates a point clearly by defining the Patient Medical History Form as a genre, thus shaping our reaction to it. We recognize this genre, so we treat it and act within it a certain way. This genre is comprised of microenvironments (the doctor, patient, nurse, and so on) which form the ecosystem as a whole. As a result, Bawarshi states we are rhetorical beings that act in these ecosystems. We are shaped by the rhetoric surrounding us and we act accordingly. We gather our impressions from rhetoric presented to us, which shapes our actions and perceptions. He also introduces exigence, motive and intention which operate on the conceptual level, motive, and what shapes our actions, exigence. Bawarshi clarifies his argument through specific examples and guides the reader via thorough genre principles. (Bawarshi)

Amy Devitt expanded the definition of genre in her 2004 essay, "A Theory of Genre." Devitt adds the ideas of recurring context of situation, context of culture, and context of genres to the definition of genre. She bases her essay on the rhetorical theory of genre and her contribution to the theory by synthesizing past work. She touches on Miller's idea of situation, but expands on it and adds that the relationship with genre and situation is reciprocal. "Genre writing" and how labeling occurs when form takes over become a prominent aspect to her definition of genre. Genre as classification system she says can help, but it occurs in many ways and under different circumstances.

Classifications

Genre and rhetoric

Genre as social action

The concept of genre is not limited to classifications and lists. People interact within genres everyday. Genre should be looked at based "on the action is is used to accomplish" by the individuals using that particular genre (Miller 151). The distance between the text or action of genre and its users does not need to be so vast. People respond to the exigencies provided by genre every day. "Exigence is a set of particular social patterns and expectations that provides a socially objectified motive for addressing" the recurring situation of a particular genre (Miller 158). Seeing genre as a social action provides the "keys to understanding how to participate in the actions of a community" (Miller 165). Carolyn Miller argues, "that a rhetorical sound definition of genre must be centered not on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish" (Miller 151).

The idea that genre is defined by rhetorical situations in which we make decisions based on commonalities and repeat those instances. Genre is not only about the form but the mere repetitiveness of similarities. Take for instance when you are in a class room setting, when you want to speak, you raise your hand, you do this because it is the correct response to speaking in turn in that social setting. If you were at lunch with a group of friends you wouldn't raise your hand to speak in turn. Miller concludes that social actions are the response to "understanding how to participate in the actions of a community" (Miller 156).

Carolyn Miller builds on previous arguments made, and particularly argues against Bitzer by giving her readers five features to understanding genre (Miller 163). She believes that if something is rhetorical there will be action. Not only will there be action, but also this action will be repeated. The repetition of action creates a regularized form of discourse. Whereas Bitzer would state that the result is that situation is the form, Miller would add that the result has more to do with the action the situation accomplished. Miller recognizes that a person chooses to take a certain social action within a defined set of rules – rules set in place by the user. A situation cannot dictate a response. Miller ends her article with the thought that genres are partly rhetorical education: "As a recurrent, significant action, a genre embodies an aspect of cultural rationality" (Miller 165). Here, Miller unknowingly encapsulates a future ideology about genre: that genres are created by culture.

Rhetorical situation

Rhetorical situation refers to the fact that every situation has the potential for a rhetorical response. Thus, the situation controls what type of rhetorical response takes place. Each situation has an appropriate response in which the rhetor can either act upon or not act upon (Bitzer). According to Bitzer, rhetorical situations come into existence, and at that point, they can either mature and go away, or mature and continue to exist. Bitzer also states that the rhetorical situation is "a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence" (Bitzer).

Reciprocity

"A genre is named because of its formal markers" (Devitt 10). By this, Amy Devitt means that people recognize genre based on the characteristics of the rhetorical situations which reoccur and therefore, create genre. However, "the formal markers can be defined because a genre has been named" (Devitt 10). Individuals recognize the characteristics of the recurring rhetorical situations as affirmation of what they already know about the preexisting genre. The rhetorical attributes of the genre act as both objects which define, and are defined by, genre. In other words, genre and rhetorical situation are reciprocals of one another (Devitt). Devitt looks at the work of Bitzer and Burke to expand upon the idea of recurring situation and further supports her theory about genre's rhetorical nature. She builds upon Miller's ideas of situation as well, and she adds the importance of context within the framework of situation. Devitt displays the reciprocal nature of genre and situation according to the individual by using an example of a grocery store list (Devitt). Anis Bawarshi points out that genre is a place in which "communicants rhetorically reproduce the very environments to which they in turn respond" (Bawarshi 71). People's recognition of, and response to, genre is an act that reproduces genre.

Antecedent genres

Written in 1975, Kathleen Jamieson's "Antecedent Genre as Rhetorical Constraint" declares that discourse is determined by rhetorical situations, as well as antecedent genres. Antecedent genres are genres of the past that are used as a basis to shape and form current rhetorical responses. When placed in an unprecedented situation, a rhetor can draw on antecedent genres of similar situations in order to guide their response. However, caution should be taken when drawing on antecedent genres because sometimes antecedent genres are capable of imposing powerful constraints (Jamieson 414). The intent of antecedent genres are to guide the rhetor toward a response consistent with situational demands, and if the situational demands are not the same as when the antecedent genre was created, the response to the situation might be inappropriate (Jamieson 414). Through three examples of discourse, the papal encycical, the early state of the union address, and congressional replies, she demonstrates how traces of antecedent genres can be found within each. These examples clarify how a rhetor will tend to draw from past experiences that are similar to the present situation in order to guide them how to act or respond when they are placed in an unprecedented situation. Jamieson explains, by use of these three examples, that choices of antecedent genre may not always be appropriate to the present situation. She discusses how antecedent genres place powerful constraints on the rhetor and may cause them to become "bound by the manacles of the antecedent genre" (Jamieson 414). These "manacles," she says, may range in level of difficultly to escape. Jamieson urges one to be careful when drawing on the past to respond to the present, because of the consequences that may follow ones choice of antecedent genre. She reiterates the intended outcome through her statement of "choice of an appropriate antecedent genre guides the rhetor toward a response consonant with situational demands" (Jamieson 414).

"Tyranny of genre"

The phrase "tyranny of genre" comes from genre theorist Richard Coe, who wrote that "the 'tyranny of genre' is normally taken to signify how generic structures constrain individual creativity" (Coe 188). If genre functions as a taxonomic classification system, it could constrain individual creativity, since "the presence of many of the conventional features of a genre will allow a strong genre identification; the presence of fewer features, or the presence of features of other genres, will result in a weak or ambiguous genre identification" (Schauber 403). Under the classification-system concept of genre, placing a text into a genre is vital, since "every text is read according to a genre which governs its interpretation" (Schauber 401). The classification-system concept results in a polarization of responses to texts that do not fit neatly into a genre or exhibit features of multiple genres: "The status of genres as discursive institutions does create constraints that may make a text that combines or mixes genres appear to be a cultural monstrosity. Such a text may be attacked or even made a scapegoat by some as well as be defended by others" (LaCapra 220).

Under the more modern understanding of the concept of genre, as "social action" à la Miller (Miller 152), enables a more situational approach to genre, which frees it from the classification-system genre's "tyranny of genre". Relying on the importance of the rhetorical situation in the concept of genre results in an exponential expansion of genre study, which benefits literary analysis. One literature professor writes, "The use of the contemporary, revised genre idea [as social action] is a breath of fresh air, and it has opened important doors in language and literature pedagogy" (Bleich 130). Instead of a codified classification as the pragmatic application of genre, the new genre idea insists that "human agents not only have the creative capacities to reproduce past action, such as action embedded in genres, but also can respond to changes in their environment, and in turn change that environment, to produce under-determined and possibly unprecedented action, such as by modifying genres" (Killoran 72).

Stabilization, homogenization and fixity

Never, is there total stabilization in a set genre, nor instances of complete lack of homogenization. However, because of the relative similarities between said terms, the amount of stabilization or homogenization a certain genre maintains is subjected to opinion or is very relative in itself. The stabilization of necessary discourse is considered perfect because it is always needed. In rhetorical situation or antecedent genres, what is unprecedented, mostly leads to stable and predictable responses. Outside the natural setting with a alternate given form of discourse, one may respond the same but may not appear appropriately because of the lack of homogenization or differing expectations in the given rhetorical situation. (Jamieson)

Fixity is uncontrolled by a given situation and is deliberately utilized by the effected before the rhetorical situation occurs. Fixity almost always directly affects stabilization, and has little to no bearing on homogenization. The choice of discourse will provide a certain value of fixity, dependent on said choice. If a situation calls for more mediated responses, the fixity of the situation is more prevalent, and therefore is attributed with a stable demand of expectations. Stability nor Fixity can be directly affected by the subject at hand. The only option is affecting homogenization which in turn, can positively or negatively affect stability. Directly choosing a fixed arena within genre inversely alters the homogenization of said chooser constituting as a new genre accompanied with modified genre subsets and a newly desired urgency. The same ideological theory can be applied to how one serves different purposes, creating either separate genres or modernized micro-genres. (Fairclough)

Genre and culture

Genre is embedded in culture, but may clash with it at times. When studying genre, there are occasions in which a cultural group may not be inclined to keep within the set structures of a genre. This is best demonstrated in Anthony Pare's study of Inuit social workers in "Genre and Identity: Individuals, Institutions and Ideology". In this study, there was a conflict between the genre of the social workers' record keeping forms and the cultural values that prohibited the Inuit social workers from fully being able to fulfill the expectations of this genre. Because the social workers worked closely with the families that they were serving, they did not want to disclose many of the details that are standard in the genre of record keeping related to this field. Giving out such information would violate close cultural ties with the members of their community. This is an example of how culture has clashed with genre. Amy Devitt further expands on the concept of culture by bringing in the idea that "culture defines what situations and genres are likely or possible" (Devitt 24). In this case, genre is not only coexisting with culture, but it is defining its very components. It is shaping the rhetorical situations that an individual may find his or herself in and in turn affects the rhetorical responses that arise out of the situation.

Genre and pop culture

Outside of the academic field, genre is employed regularly in societies' pop culture. The mass media uses genre to differentiate between classes of popular subjects such as music, movies, TV, books, etc. Favoritism plays an important part of distinguishing one genre from another; fans of Horror look differently upon Comedy than fans of Romance do. Genre has also been used to shape differences in cultural aspects of these popular subjects. American comedies are distinctly different from French ones, as Country music is noticeably unlike Irish folk music. Genres sort subjects (such as movies, music, books, etc.) efficiently, especially when following trends set by society. From walking in to the nearest movie rental store to searching for music via ITunes, genres are applicable in everyday life as organized classification systems. Even in places such as grocery stores or clothing shops, genres are utilized to form an ordered flow to determine the differences between smaller classes within one particular subject, pointing out the differences between fruit and dairy, and punk to mod.

Social construct

Miller gives detailed background on Bitzer's definition of exigence as a reaction to situation and also points towards the theory that genres recur based on Jamieson's observations. More importantly, Miller defines why these situations occur. "Situations are social constructs that are the result, not of 'perception,' but of definition" (Miller 156). From this it is understood that exigence is also socially situated. Exigence can be seen as a "social knowledge," for if exigence was based on intention it would be ill-informed or at odds with what that particular situation traditionally supports. Exigence being socially constructed gives a stronger basis for understanding and action.

Exigence when seen as a social motive eliminates danger, ignorance, vagueness and separateness. Your reaction to situation may not be sustainable to the social constructs of genre. This does not take away the fact that genre is ever evolving, but we must understand that our reactions and motives are social constructed.

Genre and audiences

Although genres are not precisely definable, genre considerations are one of the most important factors in determining what a person will see or read. Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites. Books and movies that are difficult to categorize into a genre are likely to be less successful commercially.

The term may be used in categorising web pages, like "newspage" and "fanpage", with both very different layout, audience, and intention. Some search engines like Vivísimo try to group found web pages into automated categories in an attempt to show various genres the search hits might fit.

Genre in visual arts

The term "genre" is much used in the history and criticism of visual art, but in art history has meanings that overlap rather confusingly. Genre painting is a term for paintings where the main subject features human figures to whom no specific identity attaches - in other words, figures are not portraits, characters from a story, or allegorical personifications. Many genre paintings are scenes from common life. These are distinguished from staffage: incidental figures in what is primarily a landscape or architectural painting. Genre painting may also be used as a wider term covering genre painting proper, and other specialized types of paintings such as still-life, landscapes, marine paintings and animal paintings.

The concept of the "hierarchy of genres" was a powerful one in artistic theory, especially between the 17th and 19th centuries. It was strongest in France, where it was associated with the Académie française which held a central role in academic art. The genres in hierarchical order are:

Genre in linguistics

In philosophy of language, figuring very prominently in the works of philosopher and literary scholar Mikhail Bakhtin. Bakhtin's basic observations were of "speech genres" (the idea of heteroglossia), modes of speaking or writing that people learn to mimic, weave together, and manipulate (such as "formal letter" and "grocery list", or "university lecture" and "personal anecdote"). In this sense genres are socially specified: recognized and defined (often informally) by a particular culture or community. The work of Georg Lukács also touches on the nature of literary genres, appearing separately but around the same time (1920s–1930s) as Bakhtin. Norman Fairclough has a similar concept of genre that emphasises the social context of the text: Genres are "different ways of (inter)acting discoursally" (Fairclough, 2003: 26)

However, this is just one way of conceiving genre. Charaudeau & Maingueneau determine four different analytic conceptualisations of genre.

A text's genre may be determined by its:

- linguistic function.

- formal traits.

- textual organisation.

- relation of communicative situation to formal and organisational traits of the text (Charaudeau & Maingueneau, 2002:278-280).

Genre in Literature

In literature, genre has been known as an intangible taxonomy. This taxonomy implies a concept of containment or the idea that it will be stable forever. The best-known creators of genre in literature were Plato and Aristotle.

The earliest recorded systems of genre in Western history can be traced back to Plato and Aristotle. Gérard Genette, a French literary theorist and author of The Architext, describes Plato as creating three imitational genres: dramatic dialogue, pure narrative and epic (a mixture of dialogue and narrative). Lyric poetry, the fourth and final type of Greek literature, was excluded by Plato as a non-mimetic mode. Aristotle later revised Plato's system by eliminating the pure narrative as a viable mode and distinguishing by two additional criterions: the object to be imitated, as objects could be either superior or inferior, and the medium of presentation such as words, gestures or verse. Essentially, the three categories of mode, object, and medium can be visualized along an XYZ axis. Excluding the criteria of medium, Aristotle's system distinguished four types of classical genres: tragedy (superior-dramatic dialogue), epic (superior-mixed narrative), comedy (inferior-dramatic dialogue), and parody (inferior-mixed narrative). Genette continues by explaining the later integration of lyric poetry into the classical system during the romantic period, replacing the now removed pure narrative mode. Lyric poetry, once considered non-mimetic, was deemed to imitate feelings, becoming the third leg of a new tripartite system: lyrical, epical, and dramatic dialogue. This system, which came to "dominate all the literary theory of German romanticism (and therefore well beyond)…" (38), has seen numerous attempts at expansion or revision. However, more ambitious efforts to expand the tripartite system resulted in new taxonomic systems of increasing scope and complexity. Genette reflects upon these various systems, comparing them to the original tripartite arrangement: "its structure is somewhat superior to…those that have come after, fundamentally flawed as they are by their inclusive and hierarchical taxonomy, which each time immediately brings the whole game to a standstill and produces an impasse" (74). Genette aligns himself with the early theorists as opposed to other theorists of his time period, which were highly anti-taxonomy. Taxonomy allows for more a more structured classification system of genre as opposed to a more contemporary model of genre.

References

- Bawarshi, Anis. "The Ecology of Genre." Ecocomposition: Theoretical and Pedagogical Approaches. Eds. Christian R. Weisser and Sydney I. Dobrin. Albany: SUNY Press, 2001. 69-80.

- Bitzer, Lloyd F. "The Rhetorical Situation." Philosophy and Rhetoric 1:1 (1968): 1‐14.

- Bleich, David. "The Materiality of Language and the Pedagogy of Exchange." Pedagogy 1.1 (2001): 117-141.

- Charaudeau, P.; Maingueneau, D. & Adam, J. Dictionnaire d'analyse du discours Seuil, 2002.

- Coe, Richard. "'An Arousing and Fulfillment of Desires': The Rhetoric of Genre in the Process Era - and Beyond." Genre and the New Rhetoric. Ed. Aviva Freedman and Peter Medway. London: Taylor & Francis, 1994. 181-190.

- Devitt, Amy J. "A Theory of Genre." Writing Genres. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004. 1-32.

- Fairclough, Norman. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research Routledge, 2003.

- Genette, Gérard. The Architext: An Introduction. 1979. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Jamieson, Kathleen M. "Antecedent Genre as Rhetorical Constraint." Quarterly Journal of Speech 61 (1975): 406‐415.

- Killoran, John B. "The Gnome In The Front Yard and Other Public Figurations: Genres of Self-Presentation on Personal Home Pages." Biography 26.1 (2003): 66-83.

- LaCapra, Dominick. "History and Genre: Comment." New Literary History 17.2 (1986): 219-221.

- Miller, Carolyn. "Genre as Social Action." Quarterly Journal of Speech. 70 (1984): 151-67.

- Schauber, Ellen, and Ellen Spolsky. "Stalking a Generative Poetics." New Literary History 12.3 (1981): 397-413.

Further reading

- Sullivan, Ceri (2007) 'Disposable elements? Indications of genre in early modern titles', Modern Language Review 102.3, pp. 641–53

- Pare, Anthony. "Genre and Identity." The Rhetoric and Ideology of Genre: Strategies for Stability and Change. Eds. Richard M. Coe, Lorelei Lingard, and Tatiana Teslenko. Creskill, N.J. Hampton Press, 2002.