Iron Age

| Part of a series on the |

| Iron Age |

|---|

| ↑ Bronze Age |

| ↓ Ancient history |

The Iron Age is a period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing agricultural practices, religious beliefs and artistic styles. The Iron Age as an archaelogical term indicates the condition as to civilization and culture of a people using iron as the material for their cutting tools and weapons.[1] The Iron Age is the 3rd principal period of the three-age system created by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen for classifying ancient societies and prehistoric stages of progress.[2]

The Iron Age is characterized by forms of implements, weapons, personal ornaments, and pottery, and also by systems of decorative design, which are altogether different from those of the preceding age of bronze.[1] The work of blacksmiths,[3] developing implements and weapons, are hammered into shape, and as a necessary consequence the stereotyped forms of their predecessors in bronze, which were cast, but are gradually departed from, and the system of decoration, which in the Bronze Age consisted chiefly of a repetition of rectilinear patterns, gives place to a system of curvilinear and flowing designs.[1] The term "Iron Age" has low real chronological value, for there is not a universal synchronous sequence of the three epochs in all quarters of the world.[4] The dates and context vary depending on the geographical region; the sequence is not necessarily true of every part of the earth's surface, for there are areas, such as the islands of the South Pacific, the interior of Africa, and parts of North and South America, where the peoples have passed directly from the use of stone to the use of iron without the intervention of an age of bronze.[1]

In historical archaeology, the ancient literature of the Iron Age includes the earliest texts preserved in manuscript tradition. Sanskrit literature and Chinese literature flourished in the Age. Other text includes the Avestan Gathas, the Indian Vedas and the oldest parts of the Hebrew Bible. The principal feature that distinguishes the Iron Age from the preceding ages is the introduction of alphabetic characters, and the consequent development of written language which laid the foundations of literature and historic record.[1] The prehistoric Iron age in the various regional areas then transition to the historic Iron Age,[5] i.e. the local production of ample written sources. The Iron Age is followed in chronological progression by the Middle Ages, with the Iron Age ending around 500 A.D..

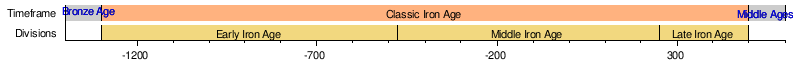

Chronology

Very little is known about human migration of the 12th to 9th centuries BC, but there were significant population movements. The Dorian invasion of Greece is conjectured to have led to the Greek Dark Ages. Groups in Anatolia and the Iranian plateau invaded the territory of the Elamite Empire. The Urartians were displaced by Armenians, and the Cimmerians and the Mushki migrated from the Caucasus into Anatolia. A Thraco-Cimmerian connection links these movements to the Proto-Celtic world of central Europe, leading to the introduction of Iron to Europe and the Celtic expansion to western Europe and the British Isles around 500 BC.

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

The modern Archaeological evidence identified the start of Iron production as taking place in Anatolia around 1200 BCE, though some contemporary archaeological evidence points to earlier dates. Around 3000 BC, iron was a scarce and precious metal in the Near East. Iron's qualities, in contrast to those of bronze, were not understood. Between 1200 BC and 1000 BC, diffusion in the understanding of iron metallurgy and utilization of iron objects was fast and far-flung. In the history of ferrous metallurgy, iron smelting — the extraction of usable metal from oxidized iron ores — is more difficult than tin and copper smelting. While these metals and their alloys can be cold-worked or melted in relatively simple furnaces (such as the kilns used for pottery) and cast into molds, smelted iron requires hot-working and can be melted only in specially designed furnaces. Thus it is not surprising that humans only mastered the technology of smelted iron after several millennia of bronze metallurgy.

It was thought that the lack of archaeological evidence of iron production made it seem unlikely that iron production was begun earlier elsewhere, and the Iron Age was seen as a case of simple diffusion of a new and superior technology from an invention point in Near East to other regions. It is known in the present age that meteoric iron, or iron-nickel alloy, was used by various ancient peoples thousands of years before the Iron Age. Such iron, being in its native metallic state, required no smelting of ores.[6][7] By the Middle Bronze Age, increasing numbers of smelted iron objects (distinguishable from meteoric iron by the lack of nickel in the product) appeared in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

Iron in its natural form is very soft, though harder than bronze, and is not useful for tools unless it is combined with carbon to make steel. The percentage of carbon determines important characteristics of the final product: the lower the carbon content the softer the product, the higher the carbon content the harder the product. The systematic production and use of iron implements in Anatolia begins around 2000 BCE.[8] Recent archaeological research in the Ganges Valley, India showed early iron working by 1800 BC.[9] However, this metal was expensive, perhaps because of the technical processes required to make steel, the most useful iron product. It is attested in both documents and in archaeological contexts as a substance used in high value items such as jewelry.

Snodgrass[10][11] suggests that a shortage of tin, as a result of the Bronze Age Collapse and trade disruptions in the Mediterranean around 1300 BC, forced metalworkers to seek an alternative to bronze. There is evidence of this in that many bronze items were recycled and made from implements into weapons during this time. With more widespread use of iron, the technology needed to produce workable steel was developed and the price lowered. As a result, even when tin became available again, iron was now the metal of choice for tools and weapons and was cheap enough that it could replace bronze.[12] Forged iron implements supersedes cast bronze tools. Iron, as a stronger and lighter material, becomes a technological advantage for civilizations using it.

Recent archaeological work has modified not only this chronology, but also the causes of the transition from bronze to iron. New dates from India suggest that iron was being worked there as early as 1800 BCE, and African sites are turning up dates as early as 1200 BCE,[13][14][15] confounding the idea that there was a simple discovery and diffusion model. Increasingly, the Iron Age in Europe is being seen as a part of the Bronze Age collapse in the ancient Near East, in ancient India (with the post-Rigvedic Vedic civilization), ancient Iran, and ancient Greece (with the Greek Dark Ages). In other regions of Europe, the Iron Age began in the 8th century BCE in Central Europe and the 6th century BCE in Northern Europe. The Near Eastern Iron Age is divided into two subsections, Iron I and Iron II. Iron I (1200–1000 BCE) illustrates both continuity and discontinuity with the previous Late Bronze Age. There is no definitive cultural break between the 13th and 12th century BCE throughout the entire region, although certain new features in the hill country, Transjordan and coastal region may suggest the appearance of the Aramaean and Sea People groups. There is evidence, however, that shows strong continuity with Bronze Age culture, although as one moves later into Iron I the culture begins to diverge more significantly from that of the late 2nd millennium.

History

During the Iron Age, the best tools and weapons were made from steel, particularly alloys which were produced with a carbon content between approximately 0.30% and 1.2% by weight. Alloys with less carbon than this, such as wrought iron, cannot be heat treated to a significant degree and will consequently be of low hardness, while a higher carbon content creates an extremely hard but brittle material that cannot be annealed, tempered, or otherwise softened. Steel weapons and tools were nearly the same weight as those of bronze, but stronger. However, steel was difficult to produce with the methods available, and alloys that were easier to make, such as wrought iron,[16] were more common in lower-priced goods. Many techniques have been used to create steel; Mediterranean ones differ dramatically from African ones, for example. Sometimes the final product is all steel, sometimes techniques like case hardening or forge welding were used to make cutting edges stronger.

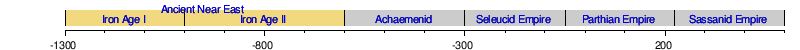

Near East

Southeast Asia / Middle East

In Chaldaea and Assyria, the initial use of iron reaches far back, to perhaps 4000 years before the Common Era.[4] One of the earliest smelted iron artifacts known is a dagger with an iron blade found in a Hattic tomb in Anatolia, dating from 2500 BC.[17] The widespread use of iron weapons which replaced bronze weapons rapidly disseminated throughout the Near East (southwest Asia) by the beginning of the 1st millennium BC.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Near East timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Ancient Near East

The Iron Age in the Ancient Near East is believed to have begun with the discovery of iron smelting and smithing techniques in Anatolia or the Caucasus and Balkans in the late 2nd millennium BC (c. 1300 BC).[19] However, this theory has been challenged by the emergence of those placing the transition in price and availability issues rather than the development of technology on its own. The earliest bloomery smelting of iron is found at Tell Hammeh, Jordan around 930 BC (C14 dating).

The development of iron smelting was once attributed to the Hittites of Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age. It was believed that they maintained a monopoly on ironworking, and that their empire had been based on that advantage.[20] Accordingly, the invading Sea Peoples were responsible for spreading the knowledge through that region. This theory is no longer held in the common current thought of the majority of scholarship,[21] since there is no archaeological evidence of the alleged Hittite monopoly. While there are some iron objects from Bronze Age Anatolia, the number is comparable to iron objects found in Egypt and other places of the same time period; and only a small number of these objects are weapons.[22] As part of the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age, the Bronze Age collapse saw the slow, comparatively continuous spread of iron-working technology in the region. The Ugaritic script was in use during this time, around 1300 BCE. Ugarit was one of the centres of the literate world.

Assyro-Babylonian literature, written in the Akkadian language, of Mesopotamia (Assyria and Babylonia) continues into the Iron Age up until the 6th centuries BC. The oldest Phoenician alphabet inscription is the Ahiram epitaph, engraved on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram from circa 1200 BC.[23] It has become conventional to refer to the alphabetic script as "Proto-Canaanite" until the mid-11th century BC, when it is first attested on inscribed bronze arrowheads, and as "Phoenician" only after 1050 BC.[24] The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet is identical to the Phoenician alphabet and dates to the 10th century BC.

Europe

In Europe, the use of iron covers the last years of the prehistoric and the early years of the historic periods.[4] The regional Iron Age may be defined as including the last stages of of the prehistoric and the first of the proto-historic periods.[1] Iron working was introduced to Europe in the late 11th century BC,[25] probably from the Caucasus and slowly spread northwards and westwards over the succeeding 500 years. The widespread use of the technology of iron was implemented in Europe simultaneously with Asia.[26]

The iron usage in northern Europe would seem to have been fairly general long before the invasion of Caesar. But iron was not in common use in Denmark until the cud of the 1st century A.D. In the north of Russia and Siberia its introduction was even as late as A.D. 800, while Ireland enters upon her Iron Age about the beginning of the 1st century. In Gaul, on the other hand, the Iron Age dates back some 500 years B.C.; while in Etruria the metal was known some six centuries earlier.[4] As the knowledge of iron seems to have traveled over Europe from the south northward, the commencement of the Iron Age was very much earlier in the southern than in the northern countries. Homer represents Greece as beginning her Iron Age twelve hundred years before 20th Century. Greece, as represented in the Homeric poems, was then in the transition period from bronze to iron, while Scandinavia was only entering her Iron Age about the time of the Common era.[4]

The Iron Age in Europe is characterized by an elaboration of designs in weapons, implements and utensils.[4] These are no longer cast but hammered into shape, and decoration is elaborate curvilinear rather than simple rectilinear, the forms and character of the ornamentation of the northern European weapons resembling in some respects Roman arms, while in others they are peculiar and evidently representative of northern art. The dead were buried in an extended position, while in the preceding Bronze Age cremation had been the rule.

European timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Eastern Europe

The early 1st millennium BC marks the Iron Age in Eastern Europe. In the Pontic steppe and the Caucasus region, the Iron Age begins with the Koban and the Chernogorovka and Novocherkassk cultures from c. 900 BC. By 800 BC, it was spreading to Hallstatt C via the alleged "Thraco-Cimmerian" migrations.

Along with Chernogorovka and Novocherkassk cultures, on the territory of ancient Russia and Ukraine the Iron Age is to a significant extent associated with Scythians, who developed iron culture since the 7th century BC. The majority of remains of their iron producing and blacksmith's industries from 5th to 3rd century BC was found near Nikopol in Kamenskoe Gorodishche, which is believed to be the specialized metallurgic region of the ancient Scythia.[27][28]

From the Hallstatt culture, the Iron Age spreads west with the Celtic expansion from the 6th century BC. In Poland, the Iron Age reaches the late Lusatian culture in about the 6th century, followed in some areas by the Pomeranian culture.

The ethnic ascriptions of many Iron Age cultures has been bitterly contested, as the roots of Germanic, Baltic and Slavic peoples were sought in this area.

Central Europe

In Central Europe, the Iron Age is generally divided in the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture (HaC and D, 800–450) and the late Iron Age La Tène culture (beginning in 450 BC). The transition from bronze to iron in Central Europe is exemplified in the great cemetery, discovered in 1846, of Hallstatt, near Gmunden, where the forms of the implements and weapons of the later part of the Bronze Age are imitated in iron. In the Swiss or La Tene group of implements and weapons the forms are new and transition complete.[1]

The Celtic culture, or rather Proto-Celtic groups, had expanded to much of Central Europe, (Gauls) and following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians). In Central Europe, the prehistoric Iron Age ends with the Roman Conquest.

Aegean

In the Greek Dark Ages, there was a widespread availability of edged weapons of iron, but a variety of explanations fits the available archaeological evidence. From around 1200 BC, the palace centres and outlying settlements of the Mycenaean culture began to be abandoned or destroyed, and by 1050 BC, the recognisable cultural features (such as Linear B script) had disappeared.

The Greek alphabet began in the 8th century BC.[29] It is descended from the Phoenician alphabet. The Greeks adapted the system, notably introducing characters for vowel sounds and thereby creating the first truly alphabetic (as opposed to abjad) writing system. As Greece sent out colonies west towards Sicily and Italy (Pithekoussae, Cumae), the influence of their alphabet extended further. The ceramic Euboean artifact inscribed with a few lines written in the Greek alphabet referring to "Nestor's cup", discovered in a grave at Pithekoussae (Ischia) dates from c. 730 BC; it seems to be the oldest written reference to the Iliad. The fragmentary Epic Cycles, a collection of Ancient Greek epic poems that related the story of the Trojan War, were a distillation in literary form of an oral tradition developed during the Greek Dark Age. The traditional material from which the literary epics were drawn treats the Mycenaean Bronze Age culture from the perspective of Iron Age and later Greece.

Southern Europe

In Italy, the Iron Age was probably introduced by the Villanovan culture but this culture is otherwise considered a Bronze Age culture, while the following Etruscan civilization is regarded as part of Iron Age proper. The Etruscans Old Italic alphabet spread throughout Italy from the 8th century. The Etruscan Iron Age was then ended with the rise and conquest of the Roman Republic, which conquered the last Etruscan city of Velzna in 265 BC.

Western Europe

The Celtic culture had expanded to the group of islands of northwest Europe (Insular Celts) and Iberia (Celtiberians, Celtici and Gallaeci). On the British Isles, the British Iron Age lasted from about 800 BC[32] until the Roman Conquest and until the 5th century in non-Romanised parts. Structures dating from this time are often impressive, for example the brochs and duns of northern Scotland and the hill forts that dotted the islands. On the Iberian peninsula, the Paleohispanic scripts began to be used between 7th century to the 5th century BC. These scripts were used until the end of the 1st century BCE or the beginning of the 1st century CE.

Northern Europe

The early Iron Age forms of Scandinavia show no traces of Roman influence, though these become abundant toward the middle of the period. The duration of the Iron Age is variously estimated according as its commencement is placed nearer to or farther from the opening years of the Christian era; but it is agreed on all hands that the last division of the Iron Age of Scandinavia, the Viking Period, is to be taken as from 700 to 1000 A.d., when paganism in those lands was superseded by Christianity.[1]

The Iron Age north of the Alps is divided into the Pre-Roman Iron Age and the Roman Iron Age. In Scandinavia, further periods followed up to AD 1100: the Migration Period, the Vendel or Merovingian Period and the Viking Period. The earliest part of the Iron Age in north-western Germany and southern Jutland was dominated by the Jastorf culture.

Early Scandinavian iron production typically involved the harvesting of bog iron. The Scandinavian peninsula, Finland and Estonia show sophisticated iron production from c. 500 BC. Metalworking and Asbestos-Ceramic pottery co-occur to some extent. Another iron ore used was iron sand (such as red soil). Its high phosphorus content can be identified in slag. Such slag is sometimes found together with asbestos ware-associated axe types belonging to the Ananjino Culture.

Asia

The widespread use of the technology of iron was implemented in Asia simultaneously with Europe.[33] In China, the use of iron reaches far back, to perhaps 4000 years before the Common era.[4]

Central Asia

The Iron Age in Central Asia began when iron objects appear among the Indo-European Saka in present-day Xinjiang between the 10th century BC and the 7th century BC, such as those found at the cemetery site of Chawuhukou.[34]

North Asia

The Pazyryk culture is an Iron Age archaeological culture (ca. 6th to 3rd centuries BC) identified by excavated artifacts and mummified humans found in the Siberian permafrost in the Altay Mountains.

South Asia

South Asia timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Indian Subcontinent

The history of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent began during the 2nd millennium BCE. Archaeological sites in India, such as Malhar, Dadupur, Raja Nala Ka Tila and Lahuradewa in present day Uttar Pradesh show iron implements in the period 1800 BC – 1200 BC.[9] Archaeological excavations in Hyderabad show an iron age burial site.[35] Rakesh Tewari[36] believes that around the beginning of the Indian Iron Age (13th century BC), iron smelting was widely practiced in India. Such use suggests that the date of the technology's inception may be around the 16th century BC.[9]

Epic India is traditionally placed around early 10th century BC and later on from the Sanskrit epics of Sanskrit literature. Composed between approximately 1500 BC and 600 BC of pre-classical Sanskrit, the Vedic literature forms four Vedas (the Rig, Yajur, Sāma and Atharva). The main period of Vedic literary activity is the 9th to 7th centuries when the various schools of thought compiled and memorized their respective corpora. Following this, the scholarship around 500 to 100 BCE organized knowledge into Sutra treatises.

The beginning of the 1st millennium BC saw extensive developments in iron metallurgy in India. Technological advancement and mastery of iron metallurgy was achieved during this period of peaceful settlements. One iron working centre in east India has been dated to the first millennium BC.[37] In Southern India (present day Mysore) iron appeared as early as 12th to 11th centuries BC; these developments were too early for any significant close contact with the northwest of the country.[37] The Indian Upanishads mention metallurgy.[38] and the Indian Mauryan period saw advances in metallurgy.[39] As early as 300 BC, certainly by AD 200, high quality steel was produced in southern India, by what would later be called the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon.[40]

The origins of the Brāhmī script dates to the 6th century BC. The contact of the Hindu Kush region with the Near East occurred with the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire under Darius the Great to the Indus valley. The script to write an Indo-Aryan languages occurred is shows up in the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. The best-known Brāhmī inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, dated to the 3rd century BCE. The Bhattiprolu script have been found in old inscriptions located in the fertile Krishna river delta and the estuary region where the river meets the Bay of Bengal. The inscriptions date to before 100 BCE,[41] putting them among the earliest evidence of Brahmi writing in South India.[42][43]

Sri Lanka

The protohistoric Early Iron Age in Sri Lanka lasted from 1000 to 600 BC. Radiocarbon evidence has been collected from Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya.[44][45][46][47] The Anuradhapura settlement is recorded to extend 10 hectares by 800 BC and grew to 50 hectares by 700 - 600 BC to become a town.[48] The skeletal remains of an Early Iron Age chief was excavated in Anaikoddai, Jaffna. The name 'Ko Veta' is engraved in Brahmi script on a seal buried with the skeleton and is assigned by the excavators to the 3rd century BCE. Ko, meaning "King" in Tamil, is comparable to such names as Ko Atan and Ko Putivira occurring in contemporary Brahmi inscriptions in south India.[49] It is also speculated that Early Iron Age sites may exist in Kandarodai, Matota, Pilapitiya and Tissamaharama.[50]

East Asia

East Asia timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

China

In China, Chinese bronze inscriptions are found around 1200 BC. The development of iron metallurgy on the Manchurian plain transpired by the 9th century BC.[51][52] The large seal script is identified with a group of characters from a book entitled Shĭ Zhoù Piān (ca. 800 BC). Iron metallurgy reached the Yangzi Valley toward the end of the 6th century BC.[53] The few objects were found at Changsha and Nanjing. The mortuary evidence suggests that the initial use of iron in Lingnan belongs to the mid-to-late Warring States period (from about 350 BC). Important non-precious husi style metal finds include Iron tools found at the Tomb at Ku-wei ts'un of the fourth century BC..[54]

The techniques used in Lingnan are a combination of bivalve moulds of distinct southern tradition and the incorporation of piece mould technology from the Zhongyuan. The products of the combination of these two periods are bells, vessels, weapons and ornaments and the sophisticated cast.

An Iron Age culture of the Tibetan Plateau has tentatively been associated with the Zhang Zhung culture described in early Tibetan writings.

Korea

Iron objects were introduced to the Korean peninsula through trade with chiefdoms and state-level societies in the Yellow Sea area in the 4th century BC, just at the end of the Warring States Period but before the Western Han Dynasty began.[55][56] Yoon proposes that iron was first introduced to chiefdoms located along North Korean river valleys that flow into the Yellow Sea such as the Cheongcheon and Taedong Rivers.[57] Iron production quickly followed in the 2nd century BC, and iron implements came to be used by farmers by the 1st century in southern Korea.[55] The earliest known cast-iron axes in southern Korea are found in the Geum River basin. The time that iron production begins is the same time that complex chiefdoms of Proto-historic Korea emerged. The complex chiefdoms were the precursors of early states such as Silla, Baekje, Goguryeo, and Gaya[56][58] Iron ingots were an important mortuary item and indicated the wealth or prestige of the deceased in this period.[59]

Japan

The Yayoi period is an era in the history of Japan from about 300 BC to AD 300.[60] Distinguishing characteristics of the Yayoi period include the appearance of new pottery styles and the start of an intensive rice agriculture in paddy fields. The Yayoi followed the Jōmon period (14,000 BC to 300 BC) and Yayoi culture flourished in a geographic area from southern Kyūshū to northern Honshū.

The succeeding Kofun period lasts from around 250 to 538. The word kofun is Japanese for the type of burial mounds dating from this era. The Kofun and the subsequent Asuka periods are sometimes referred to collectively as the Yamato period. Iron items, such as tools, weapons, and decorative objects, are postulated to have entered Japan during this era or the late Yayoi period, most likely through contacts with the Korean Peninsula and China.

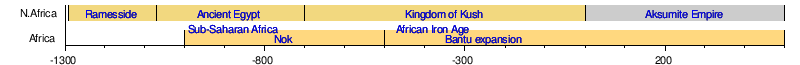

Africa

In Africa, where there was been no continent-wide universal Bronze Age, the use of iron succeeded immediately the use of stone.[4] Metallurgy was characterized by the absence of a Bronze Age, and the transition from "stone to steel" in tool substances. Sub-Saharan Africa has produced very early instances of carbon steel found to be in production around 2000 years before present in northwest Tanzania, based on complex preheating principles. The Meroitic script was developed in the Napatan Period (c. 700–300 BCE).

Africa Timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Ancient Egypt

In the Black Pyramid of Abusir, at least 3000 B.C., Gaston Maspero found some pieces of iron, and in the funeral text of Pepi I, the metal is mentioned. [4] A sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah as well as a battle axe with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit.[61]

Iron metal is singularly scarce in collections of Egyptian antiquities. Bronze remained the primary material there until the conquest by Assyria. The explanation of this would seem to lie in the fact that the relics are in most cases the paraphernalia of tombs, the funereal vessels and vases, and iron being considered an impure metal by the ancient Egyptians it was never used in their manufacture of these or for any religious purposes. It was attributed to Seth, the spirit of evil who according to Egyptian tradition governed the central deserts of Africa.[4]

Sub-Saharan

Discoveries of very early copper and bronze working sites in Niger, however, can still support that iron working may have developed in that region and spread elsewhere. Iron metallurgy has been attested very early, the earliest instances of iron smelting in Termit, Niger may date to as early as 1200 BC.[13] It was once believed that iron and copper working in Sub-Saharan Africa spread in conjunction with the Bantu expansion, from the Cameroon region to the African Great Lakes in the 3rd century BC, reaching the Cape around AD 400.[13]

Sub-Saharan Africa has produced very early instances of carbon steel found to be in production around 2000 years before present in northwest Tanzania, based on complex preheating principles. These discoveries, according to Schmidt and Avery (archaeologists credited with the discovery) are significant for the history of metallurgy.[62]

At the end of the Iron Age, Nubia became a major manufacturer and exporter of iron. This was after being expelled from Egypt by Assyrians, who used iron weapons.[63]

Gallery

| Iron Age Examples | |

|---|---|

| |

See also

- General

- Fogou

- Lists

- List of archaeological periods, List of archaeological sites

- Metallurgy

- Blast furnace, Roman metallurgy

- Other

- Synoptic table of the principal old world prehistoric cultures

Further reading

- Waldbaum, Jane C. From Bronze to Iron. Göteburg: Paul Astöms Förlag (1978): 56-8

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Junior Encyclopedia Britannica: A referemce library of general knowledge. (1897). Chicago: E.G. Melvin.

- ^ C. J. Thomsen and Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae first applied the system to artifacts.

- ^ this is what is usually meant when referring just to a "Smith"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chisholm, H. (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica. New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co.

- ^ Such literate, historical-period societies are studied in historical archaeology.

- ^ Archaeomineralogy, p. 164, George Robert Rapp, Springer, 2002

- ^ Understanding materials science, p. 125, Rolf E. Hummel, Springer, 2004

- ^ Ironware piece unearthed from Turkey found to be oldest steel in The Hindu, Thursday, March 26, 2009

- ^ a b c The origins of Iron Working in India: New evidence from the Central Ganga plain and the Eastern Vindhyas by Rakesh Tewari (Director, U.P. State Archaeological Department)

- ^ A.M.Snodgrass (1967), "Arms and Armour of the Greeks". (Thames & Hudson, London)

- ^ A. M. Snodgrass (1971), "The Dark Age of Greece" (Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh).

- ^ Theodore Wertime and J. D. Muhly, eds. The Coming of the Age of Iron (New Haven, 1980).

- ^ a b c Duncan E. Miller and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa' Journal of African History 35 (1994) 1–36; Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' Current Anthropology 1968.

- ^ How Old is the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa? — by Roderick J. McIntosh, Archaeological Institute of America (1999)

- ^ Iron in Sub-Saharan Africa — by Stanley B. Alpern (2005)

- ^ A Brief History of Iron and Steel Production by Professor Joseph S. Spoerl (Saint Anselm College)

- ^ Richard Cowen () The Age of Iron Chapter 5 in a series of essay s on Geology, History, and People prepares for a course of the University of California at Davis. Online version.

- ^ Alex Webb, "Metalworking in Ancient Greece"

- ^ Jane C. Waldbaum, From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean (Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. LIV, 1978).

- ^ Muhly, James D. 'Metalworking/Mining in the Levant' pp. 174-183 in Near Eastern Archaeology ed. Suzanne Richard (2003), pp. 179-180.

- ^ Muhly, James D. 'Metalworking/Mining in the Levant' pp. 174-183 in Near Eastern Archaeology ed. Suzanne Richard (2003), pp. 179-180.

- ^ Waldbaum, Jane C. From Bronze to Iron. Göteburg: Paul Astöms Förlag (1978): 56-8.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian, Writing Systems of the World, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 1989. p. 141.

- ^ Markoe, Glenn E., Phoenicians. University of California Press. p. 111 ISBN 0-520-22613-5

- ^ Riederer, Josef; Wartke, Ralf-B.: "Iron", Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.): Brill's New Pauly, Brill 2009

- ^ John Collis, "The European Iron Age" (1989)

- ^ Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd edition, entry on "Железный век", available online here

- ^ Christian, D. A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Blackwell Publishing, 1998, p. 141, available online

- ^ Cook, B. F. Greek Inscriptions 1987

- ^ Maiden Castle, English Heritage, retrieved 2009-05-31

- ^ Maiden Castle, Pastscape.org.uk, retrieved 2009-05-27

- ^ Haselgrove, C. and Pope, R. (2007), 'Characterising the Earlier Iron Age', in C. Haselgrove and R. Pope (eds.), The Earlier Iron Age in Britain and the Near Continent. (Oxbow, Oxford)

- ^ John Collis, "The European Iron Age" (1989)

- ^ Mark E. Hall, "Towards an absolute chronology for the Iron Age of Inner Asia," Antiquity 71.274 [1997], 863-74.

- ^ "News By Industry". The Times Of India. 2008-09-10.

- ^ Director of Archaeology, (Uttar Pradesh)

- ^ a b Early Antiquity By I. M. Drakonoff. Published 1991. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226144658. pg 372

- ^ Upanisads By Patrick Olivelle. Published 1998. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192835769. pg xxix

- ^ The New Cambridge History of India By J. F. Richards, Gordon Johnson, Christopher Alan Bayly. Published 2005. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521364248. pg 64

- ^ Juleff, G. (1996), "An ancient wind powered iron smelting technology in Sri Lanka", Nature, 379 (3): 60–63.

- ^ Richard Salomon, Indian epigraphy: a guide to the study of inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan languages Oxford University Press US, 1998. p. 34 (cf. cites one estimate of "not later than 200 BC", and of "about the end of the 2nd century B.C.")

- ^ The Bhattiprolu Inscriptions, G. Buhler, 1894, Epigraphica Indica, Vol.2

- ^ Buddhist Inscriptions of Andhradesa, Dr. B.S.L Hanumantha Rao, 1998, Ananda Buddha Vihara Trust, Secunderabad

- ^ Lahiru Weligamage (2002) The Ancient Sri Lanka

- ^ Deraniyagala, Siran, The Prehistory of Sri Lanka; an ecological perspective. (revised ed.), Colombo: Archaeological Survey Department of Sri Lanka, 1992: 709-29

- ^ Karunaratne and Adikari 1994, Excavations at Aligala prehistoric site. In: Bandaranayake and Mogren (1994). Further studies in the settlement archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla region. Sri Lanka, University of Kelaniya: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeolog :58

- ^ Mogren 1994. Objectives, methods, constraints and perspectives. In: Bandaranayake and Mogren (1994) Further studies in the settlement archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla region. Sri Lanka, University of Kelaniya: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeolog: 39.

- ^ F. R. Allchin 1989. City and state formation in Early Historic South Asia. South Asian Studies 5:1-16: 3

- ^ Indrapala, K. The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp. 324

- ^ Deraniyagala, Siran, The Prehistory of Sri Lanka; an ecological perspective. (revised ed.), Colombo: Archaeological Survey Department of Sri Lanka, 1992: 730-2, 735

- ^ Derevianki, A. P. 1973. Rannyi zheleznyi vek Priamuria

- ^ David N. Keightley. The Origins of Chinese civilization. Page 226.

- ^ Higham, Charles. 1996. The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia

- ^ Encyclopedia of World Art: Landscape in art to Micronesian cultures. McGraw-Hill. 1964.

- ^ a b Kim, Do-heon. 2002. Samhan Sigi Jujocheolbu-eui Yutong Yangsang-e Daehan Geomto [A Study of the Distribution Patterns of Cast Iron Axes in the Samhan Period]. Yongnam Kogohak [Yongnam Archaeological Review] 31:1–29.

- ^ a b Taylor, Sarah. 1989. The Introduction and Development of Iron Production in Korea. World Archaeology 20(3):422–431.

- ^ Yoon, Dong-suk. 1989. Early Iron Metallurgy in Korea. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 8(1):92–99.

- ^ Barnes, Gina L. 2001. State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Curzon, London.

- ^ Lee, Sung-joo. 1998. Silla - Gaya Sahoe-eui Giwon-gwa Seongjang [The Rise and Growth of Silla and Gaya Society]. Hakyeon Munhwasa, Seoul.

- ^ Prehistoric Archaeological Periods in Japan, Charles T. Keally

- ^ Richard Cowen, 'The Age of Iron Chapter 5 in a series of essay s on Geology, History, and People prepares for a course of the University of California at Davis. Online version

- ^ Peter Schmidt, Donald H. Avery. Complex Iron Smelting and Prehistoric Culture in Tanzania, Science 22 September 1978: Vol. 201. no. 4361, pp. 1085 - 1089

- ^ Collins, Rober O. and Burns, James M. The History of Sub-Saharan Africa. New York:Cambridge University Press, p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-68708-9.

External links

- General

- A site with a focus on Iron Age Britain from resourcesforhistory.com

- About Iron Age China and Europe

- Publications

- Andre Gunder Frank and William R. Thompson, Early Iron Age economic expansion and contraction revisited. American Institute of Archaeology, San Francisco, Ca., January, 2004.

- News

- Mass burial suggests massacre at Iron Age hill fort. Archaeologists have found evidence of a massacre linked to Iron Age warfare at a hill fort in Derbyshire. BBC. 17 April 2011