Earl Warren

Earl Warren | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office October 2, 1953[1] – June 23, 1969 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Fred M. Vinson |

| Succeeded by | Warren E. Burger |

| 30th Governor of California | |

| In office January 4, 1943 – October 5, 1953 | |

| Lieutenant | Frederick Houser (1943–1947) Goodwin Knight (1947–1953) |

| Preceded by | Culbert Olson |

| Succeeded by | Goodwin Knight |

| 20th Attorney General of California | |

| In office January 3, 1939 – January 4, 1943 | |

| Governor | Culbert Olson |

| Preceded by | Ulysses S. Webb |

| Succeeded by | Robert W. Kenny |

| Alameda County District Attorney | |

| In office 1925–1939 | |

| Preceded by | Ezra Decoto |

| Succeeded by | Ralph E. Hoyt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 19, 1891 Los Angeles, California |

| Died | July 9, 1974 (aged 83) Washington, D.C. |

| Spouse | Nina Elisabeth Meyers |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1918 |

| Rank | |

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American jurist and politician who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States and the 30th Governor of California.

He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring "one-man-one vote" rules of apportionment. He made the Court a power center on a more even base with Congress and the presidency especially through four landmark decisions: Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), Reynolds v. Sims (1964), and Miranda v. Arizona (1966).

Warren is one of only two people to be elected Governor of California three times, the other being Jerry Brown. Before holding these positions, he was a district attorney for Alameda County, California, and Attorney General of California.

Warren was also the vice-presidential nominee of the Republican Party in 1948, and chaired the Warren Commission, which was formed to investigate the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Education, early career, and military service

Earl Warren was born in Los Angeles, California, on March 19, 1891 to Methias H. Warren, a Norwegian immigrant whose original family name was Varren,[2] and Crystal Hernlund, a Swedish immigrant. Methias Warren was a longtime employee of the Southern Pacific Railroad. After the father was blacklisted for joining in a strike, the family moved to Bakersfield, California, in 1894, where the father worked in a railroad repair yard, and the son had summer jobs in railroading.

Earl grew up in Bakersfield, California where he attended Washington Junior High and Kern County High School (now called Bakersfield High School). It was in Bakersfield that Warren's father was murdered during a robbery by an unknown killer. Warren graduated the University of California, Berkeley, (B.A. 1912) in Legal Studies, and Boalt Hall, LL.B. in 1914. He was a member of The Gun Club secret society,[3] and the Sigma Phi Society, a fraternity with which he maintained lifelong ties. Warren was admitted to the California bar in 1914. He was strongly influenced by Hiram Johnson and other leaders of the Progressive Era to oppose corruption and promote democracy.[4]

Warren worked a year for an oil company and then joined Robinson & Robinson, a law firm in Oakland. In August 1917, Warren enlisted in the U.S. Army for World War I service. Assigned to the 91st Division at Camp Lewis, Washington, 1st Lieutenant Earl Warren was discharged in 1918. He served as a clerk of the Judicial Committee for the 1919 Session of the California State Assembly (1919–1920), and as the deputy city attorney of Oakland (1920–25). At this time Warren came to the attention of powerful Republican Joseph R. Knowland, publisher of The Oakland Tribune. In 1925, Warren was appointed district attorney of Alameda County. Warren was re-elected to three four-year terms. Warren vigorously investigated allegations that a deputy sheriff was taking bribes in connection with street-paving arrangements. He was a tough-on-crime district attorney (1925–1939) who professionalized the DA's office. Warren cracked down on bootlegging and had a reputation for high-handedness, but none of his convictions were overturned on appeal. On the other hand the Warren Court later declared unconstitutional some of the standard techniques he and other DAs used in the 1920s, such as coerced confessions and wiretapping.[5]

Warren soon gained a statewide reputation as a tough, no-nonsense district attorney who fought corruption in government; a 1931 survey voted listed him as the best district attorney in the country. He ran his office in a nonpartisan manner and strongly supported the autonomy of law enforcement agencies. But he also believed that police and prosecutors had to act fairly, and much of what would later lie at the heart of the Warren Court's revolution in criminal justice can be traced back to his days as an active prosecuting attorney.[6]

Family

Warren married Swedish-born widow Nina Elisabeth Palmquist on October 4, 1925 and had six children. Mrs. Warren died in Washington, at age 100 on April 24, 1993. Warren is the father of Virginia Warren; she married veteran radio and television personality John Charles Daly, on December 22, 1960. They had three children, two boys and a girl.

Attorney General of California

In 1938 he won the primaries in all major parties, thanks to a system called "cross filing," and was elected without serious opposition. Once elected he organized state law enforcement officials into regions and led a statewide anti-crime effort. One of his major initiatives was to crack down on gambling ships operating off the coast of Southern California.[7]

As Attorney General, Warren is most remembered for being the moving force behind Japanese internment during the war—the compulsory removal of people of Japanese descent to inland internment camps away from the war zone along the coast. Following the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Warren organized the state's civilian defense program, warning in January, 1942, that, "The Japanese situation as it exists in this state today may well be the Achilles heel of the entire civilian defense effort."[8] Throughout his lifetime, Warren maintained that this seemed to be the right decision at the time.[9]

Governor of California

Running as a Republican, Warren was elected Governor of California on November 3, 1942, defeating incumbent Culbert Olson, a liberal Democrat. Thanks to cross-filing he won all the 1946 primaries and was reelected with over 90% of the vote against minor candidates. He was elected to a third term (as a Republican) in 1950 becoming the first person elected governor of California three times. Warren is the only man who has been sent to office in three consecutive California gubernatorial elections. An amendment passed in 1990 sets a limit of two terms for governor. In 2010, Jerry Brown became the second person to be elected three times, in 1974, 1978, and 2010. As he served before the amendment was passed he was not prohibited from serving another term.

As governor Warren modernized the office of governor, and state government generally. Like most progressives, Warren believed in efficiency and planning. During World War II he aggressively pursued postwar economic planning. Fearing another postwar decline that would rival the depression years, Governor Earl Warren initiated public works projects similar to those of the New Deal to capitalize on wartime tax surpluses and provide jobs for returning veterans. Warren also built up the state's higher education system based on the University of California and its vast network of small universities and community colleges.[10] For example, his support of the Collier-Burns Act in 1947 raised gasoline taxes that funded a massive program of freeway construction. Unlike states where tolls or bonds funded highway construction, California's gasoline taxes were earmarked for building the system. Warren's support for the bill was crucial because his status as a popular governor strengthened his views, in contrast with opposition from trucking, oil, and gas lobbyists. The Collier-Burns Act helped influence passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956, setting a pattern for national highway construction.[11]

Warren ran for Vice President of the United States in 1948 on the Republican ticket with Thomas Dewey. Heavily favored to win, they lost in a stunning upset to incumbent President Harry Truman and his VP running mate Alben Barkley.

U.S. Supreme Court

Appointed to Supreme Court

In 1952, Warren stood as a "favorite son" candidate of California for the Republican nomination for President, hoping to be a power broker in a convention that might be deadlocked. But Warren had to head off a revolt by Senator Richard M. Nixon who supported General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower and Nixon were elected, and the bad blood between Warren and Nixon was apparent. Eisenhower offered, and Warren accepted, the post of solicitor general, with the promise of a seat on the Supreme Court. But before it was announced, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson unexpectedly died in September 1953 and Eisenhower picked Warren to replace him as Chief Justice of the United States.[12] The president wanted an experienced jurist[dubious – discuss] who could appeal to liberals in the party as well as law-and-order conservatives, noting privately that Warren "represents the kind of political, economic, and social thinking that I believe we need on the Supreme Court.... He has a national name for integrity, uprightness, and courage that, again, I believe we need on the Court".[13] In the next few years Warren led the Court in a series of liberal decisions that revolutionized the role of the Court. Eisenhower later remarked that his appointment was "the biggest damned-fool mistake I ever made."[14]

As of 2011, Warren was the last Supreme Court justice to have served as Governor of a U.S. state, the last justice to have been elected to statewide elected office, and the last serving politician to be elevated to the Supreme Court.

The Warren Court

Warren took his seat October 5, 1953 on a recess appointment; the Senate confirmed him on March 1, 1954. Despite his lack of judicial experience, his years in the Alameda County district attorney's office and as state attorney general gave him far more knowledge of the law in practice than most other members of the Court had. Warren's greatest asset, what made him in the eyes of many of his admirers "Super Chief," was his political skill in manipulating the other justices. Over the years his ability to lead the Court, to forge majorities in support of major decisions, and to inspire liberal forces around the nation, outweighed his intellectual weaknesses. Warren realized his weakness and asked the senior associate justice, Hugo L. Black, to preside over conferences until he became accustomed to the drill. A quick study, Warren soon was in fact, as well as in name, the Court's chief justice.[15]

All the justices had been appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt or Truman, and all were committed New Deal liberals. They disagreed about the role that the courts should play in achieving liberal goals. The Court was split between two warring factions. Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson led one faction, which insisted upon judicial self-restraint and insisted courts should defer to the policymaking prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black and William O. Douglas led the opposing faction; they agreed the court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy, but felt the judicial agenda had been transformed from questions of property rights to those of individual liberties, and in this area courts should play a more activist role. Warren's belief that the judiciary must seek to do justice placed him with the activists, although he did not have a solid majority until after Frankfurter's retirement in 1962.[16]

Constitutional historian Melvin I. Urofsky concludes that, "Scholars agree that as a judge, Warren does not rank with Louis Brandeis, Black, or Brennan in terms of jurisprudence. His opinions were not always clearly written, and his legal logic was often muddled."[17][18] His strength lay in his public gravitas, his leadership skills and in his firm belief that the Constitution guaranteed natural rights and that the Court had a unique role in protecting those rights.[19][20]

Political conservatives attacked his rulings as inappropriate and have called for courts to be deferential to the elected political branches. Political liberals sometimes argued[21] that the Warren Court went too far in some areas, but insist that most of its controversial decisions struck a responsive chord in the nation and have become embedded in the law.[22][dubious – discuss]

Decisions

Warren was a more liberal justice than anyone had anticipated.[23] Warren was able to craft a long series of landmark decisions because he built a winning coalition. When Frankfurter retired in 1962 and President John F. Kennedy named labor lawyer Arthur Goldberg to replace him, Warren finally had the fifth liberal vote for his majority. William J. Brennan, Jr., a liberal Democrat appointed by Eisenhower in 1956, was the intellectual leader of the activist faction that included Black and Douglas. Brennan complemented Warren's political skills with the strong legal skills Warren lacked. Warren and Brennan met before the regular conferences to plan out their strategy.[24]

Brown (1954)

Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954) banned the segregation of public schools. The very first case put Warren's leadership skills to an extraordinary test. The NAACP had been waging a systematic legal fight against the "separate but equal" doctrine enunciated in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and finally had challenged Plessy in a series of five related cases, which had been argued before the Court in the spring of 1953. However the justices had been unable to decide the issue and ordered a reargument of the case in fall 1953, with special attention to whether the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause prohibited the operation of separate public schools for whites and blacks.[25]

While all but one justice personally rejected segregation, the self-restraint faction questioned whether the Constitution gave the Court the power to order its end, especially since the Court, in several cases decided subsequent to Plessy, had upheld the doctrine of "separate but equal" as constitutional.[26] The activist faction believed the Fourteenth Amendment did give the necessary authority and were pushing to go ahead. Warren, who held only a recess appointment, held his tongue until the Senate, dominated by southerners, confirmed his appointment. Warren told his colleagues after oral argument that he believed racial segregation violated the Constitution and that only if one considered African Americans inferior to whites could the practice be upheld. But he did not push for a vote. Instead, he talked with the justices and encouraged them to talk with each other as he sought a common ground on which all could stand. Finally he had eight votes, and the last holdout, Stanley Reed of Kentucky, agreed to join the rest. Warren drafted the basic opinion in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and kept circulating and revising it until he had an opinion endorsed by all the members of the Court.[27]

The unanimity Warren achieved helped speed the drive to desegregate public schools, which mostly came about under President Richard M. Nixon. Throughout his years as Chief, Warren succeeded in keeping all decisions concerning segregation unanimous. Brown applied to schools, but soon the Court enlarged the concept to other state actions, striking down racial classification in many areas. Congress ratified the process in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Warren did compromise by agreeing to Frankfurter's demand that the Court go slowly in implementing desegregation; Warren used Frankfurter's suggestion that a 1955 decision (Brown II) include the phrase "all deliberate speed."[28]

The Brown decision of 1954 marked, in dramatic fashion, the radical shift in the Court's—and the nation's—priorities from issues of property rights to civil liberties. Under Warren the courts became an active partner in governing the nation, although still not coequal. Warren never saw the courts as a backward-looking branch of government.

The Brown decision was a powerful moral statement clad in a weak constitutional analysis; Warren was never a legal scholar on a par with Frankfurter or a great advocate of particular doctrines, as was Black. Instead, he believed that in all branches of government common sense, decency, and elemental justice were decisive, not stare decisis, tradition or the text of the Constitution. He wanted results. He never felt that doctrine alone should be allowed to deprive people of justice. He felt racial segregation was simply wrong, and Brown, whatever its doctrinal defects, remains a landmark decision primarily because of Warren's interpretation of the equal protection clause to mean that children should not be shunted to a separate world reserved for minorities.[29]

Reapportionment

The "one man, one vote" cases (Baker v. Carr and Reynolds v. Sims) of 1962–1964 had the effect of ending the over-representation of rural areas in state legislatures, as well as the under-representation of suburbs. Central cities—which had long been under-represented—were now losing population to the suburbs and were not greatly affected.

Warren's priority on fairness shaped other major decisions. In 1962, over the strong objections of Frankfurter, the Court agreed that questions regarding malapportionment in state legislatures were not political issues, and thus were not outside the Court's purview. For years, underpopulated rural areas had deprived metropolitan centers of equal representation in state legislatures. In Warren's California, Los Angeles County had only one state senator. Cities had long since passed their peak, and now it was the middle class suburbs that were underepresented. Frankfurter insisted that the Court should avoid this "political thicket" and warned that the Court would never be able to find a clear formula to guide lower courts in the rash of lawsuits sure to follow. But Douglas found such a formula: "one man, one vote."[30]

In the key apportionment case Reynolds v. Sims (1964)[31] Warren delivered a civics lesson: "To the extent that a citizen's right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen," Warren declared. "The weight of a citizen's vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives. This is the clear and strong command of our Constitution's Equal Protection Clause." Unlike the desegregation cases, in this instance, the Court ordered immediate action, and despite loud outcries from rural legislators, Congress failed to reach the two-thirds needed pass a constitutional amendment. The states complied, reapportioned their legislatures quickly and with minimal troubles. Numerous commentators have concluded reapportionment was the Warren Court's great "success" story.[32]

Due process and rights of defendants (1963-66)

In Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) the Court held that the Sixth Amendment required that all indigent criminal defendants receive publicly-funded counsel (Florida law, consistent with then-existing Supreme Court precedent reflected in the case of Powell v. Alabama, required the assignment of free counsel to indigent defendants only in capital cases); Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) required that certain rights of a person interrogated while in police custody be clearly explained, including the right to an attorney (often called the "Miranda warning").

While most Americans eventually agreed that the Court's desegregation and apportionment decisions were fair and right, disagreement about the "due process revolution" continues into the 21st century. Warren took the lead in criminal justice; despite his years as a tough prosecutor, he always insisted that the police must play fair or the accused should go free. Warren was privately outraged at what he considered police abuses that ranged from warrantless searches to forced confessions.

Warren’s Court ordered lawyers for indigent defendants, in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), and prevented prosecutors from using evidence seized in illegal searches, in Mapp v. Ohio (1961). The famous case of Miranda v. Arizona (1966) summed up Warren's philosophy.[33] Everyone, even one accused of crimes, still enjoyed constitutionally protected rights, and the police had to respect those rights and issue a specific warning when making an arrest. Warren did not believe in coddling criminals; thus in Terry v. Ohio (1968) he gave police officers leeway to stop and frisk those they had reason to believe held weapons.

Conservatives angrily denounced the "handcuffing of the police."[34] Violent crime and homicide rates shot up nationwide; in New York City, for example, after steady to declining trends until the early 1960s, the homicide rate doubled in the period from 1964-74 from just under 5 per 100,000 at the beginning of that period to just under 10 per 100,000 in 1974. After 1992 the homicide rates fell sharply.[35]

First Amendment

The Warren Court's activism stretched into a new turf, especially First Amendment rights. The Court's decision outlawing mandatory school prayer in Engel v. Vitale (1962) brought vehement complaints that echoed into the next century.[36]

Warren worked to nationalize the Bill of Rights by applying it to the states. Moreover, in one of the landmark cases decided by the Court, Griswold v. Connecticut (1963), the Warren Court announced a constitutionally protected right of privacy.[37]

With the exception of the desegregation decisions, few decisions were unanimous. The eminent scholar Justice John Marshall Harlan II took Frankfurter's place as the Court's self-constraint spokesman, often joined by Potter Stewart and Byron R. White. But with the appointment of Thurgood Marshall, the first black justice, and Abe Fortas (replacing Goldberg), Warren could count on six votes in most cases.[38]

Retirement delayed

In June 1968, Warren, fearing that Nixon would be elected president that year, worked out a retirement deal with President Johnson. Associate Justice Abe Fortas, who was secretly Johnson's top adviser, brokered the deal in which Fortas would become chief justice. The plan was foiled by the Senate, which ripped into Fortas's record and refused to confirm him. Warren remained on the Court, and Nixon was elected. In 1969 Warren learned that Fortas had made a secret lifetime contract for $20,000 a year to provide private legal advice to Louis Wolfson, a friend and financier in deep legal trouble; Warren immediately demanded and got Fortas' resignation.[39]

Warren presided over the Court's October 1968 term and retired in spring 1969; Nixon named Warren E. Burger to succeed him. Burger, despite his distinguished profile and conservative reputation, was not effective in stopping Brennan's liberalism, so the "Warren Court" remained effective until about 1986, when William Rehnquist became Chief Justice and took control of the agenda.[40]

Warren Commission

President Johnson demanded in the name of patriotic duty that Warren head the governmental commission that investigated the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It was an unhappy experience for Warren, who did not want the assignment. As a judge, he valued candor and justice, but as a politician he recognized the need for secrecy in some matters. He insisted that the commission report should be unanimous, and so he compromised on a number of issues in order to get all the members to sign the final version. But many conspiracy theorists have attacked the commission's findings ever since, claiming that key evidence is missing or distorted and that there are many inconsistencies in the report. The Commission concluded that the assassination was the result of a single individual, Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone.[41][42] Fears of possible Soviet or Cuban foreign involvement in the assassination necessitated the establishment of a bipartisan commission that, in turn, sought to depoliticize Oswald's role by downplaying his Communist affiliations. The commission weakened its findings by not sharing the government's deepest secrets. The report's lack of candor furthered antigovernment cynicism, which in turn stimulated conspiracy theorists who propounded any number of alternative scenarios, all mutually contradictory.[43][44]

Legacy

Earl Warren had a profound impact on the Supreme Court and United States of America. As Chief Justice, his term of office was marked by numerous rulings on civil rights, separation of church and state, and police arrest procedure in the United States.

His critics found him a boring person. "Although Warren was an important and courageous figure and although he inspired passionate devotion among his followers...he was a dull man and a dull judge," wrote Dennis J. Hutchinson.[45]

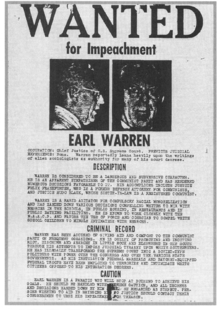

Warren retired from the Supreme Court in 1969. He was affectionately known by many as the "Superchief", although he became a lightning rod for controversy among conservatives: signs declaring "Impeach Earl Warren" could be seen around the country throughout the 1960s. The unsuccessful impeachment drive was a major focus of the John Birch Society.[46]

As Chief Justice, he swore in Presidents Eisenhower (in 1957), Kennedy (in 1961), Johnson (in 1965) and Nixon (in 1969).

Death

Five and a half years after his retirement, Warren died in Washington, D.C., on July 9, 1974.[47] His funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral and his body was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[48]

Honors

On December 5, 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady of California Maria Shriver inducted Warren into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts.[49] The Earl Warren Bill of Rights Project is named in his honor. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously in 1981. An extensive collection of Warren's papers, including case files from his Supreme Court service, is located at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Most of the collection is open for research.

Various things are named in his honor. In 1977, Fourth College, one of the six undergraduate colleges at the University of California, San Diego, was renamed Earl Warren College in his honor. The California State Building in San Francisco, a middle school in Solana Beach, California, elementary schools in Garden Grove and Lake Elsinore, California, a middle school in his home town of Bakersfield, California, high schools in San Antonio, Texas (Earl Warren High School) and Downey, California, and a building at the high school he attended (Bakersfield High School) are named for him, as are the showgrounds in Santa Barbara, California. The freeway portion of State Route 13 in Alameda County is the Warren Freeway.

He was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 29¢ Great Americans series postage stamp.

Electoral history

|

Earl Warren electoral history |

|---|

|

California Republican presidential primary, 1936:[51]

1936 Republican presidential primaries[52]:

Republican primary for Governor of California, 1942[53]:

Democratic primary for Governor of California, 1942[54]:

California gubernatorial election, 1942[55]:

California Republican presidential primary, 1944[56]

1944 Republican presidential primaries[57]:

Republican primary for Governor of California, 1946[58]:

Democratic primary for Governor of California, 1946[59]:

California gubernatorial election, 1946[60]:

1948 Republican presidential primaries[61]:

1948 Republican National Convention (Presidential tally)[62]

1948 Republican National Convention (Vice Presidential tally)[63]:

United States presidential election, 1948

California gubernatorial election, 1950[64]:

1952 Republican presidential primaries[65]:

1952 Republican National Convention (1st ballot)

1952 Republican National Convention (2nd ballot)

|

See also

Articles about his time as Chief Justice Template:Multicol

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- Super Chief: The Life and Legacy of Earl Warren, a 1989 documentary film

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

Articles about his time before becoming Chief Justice

- Earl King, Ernest Ramsay, and Frank Conner, murder case he prosecuted in Alameda County, California

Cultural references

In the 1992 Simpsons episode "Itchy and Scratchy: The Movie", Marge frets over Bart's poor behavior and lack of self-discipline, to the point that she imagines a future adult version of him as an overweight, slovenly, male stripper, instead of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, which she had previously hoped for. When she then urges her husband Homer to subsequently punish their ten-year-old boy, his initial reluctance to do so prompts her to ask, "Do you want your son to become Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, or a sleazy male stripper?", to which Homer responds, "Can't he be both, like the late Earl Warren?" When Marge corrects him by saying, "Earl Warren wasn't a stripper!", Homer replies dismissively, "Now who's being naïve?" [66] Mentioned in Stephen King's novel 11/22/63.

References

- ^ "Federal Judicial Center: Earl Warren". 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Camille Gavin and Kathy Leverett, Kern's Movers and Shakers, Kern View Foundation (1987), 208 pps., page 199

- ^ "National Affairs: EARL WARREN, THE 14th CHIEF JUSTICE". Time. October 12, 1953. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ G. Edward White, Earl Warren, a public life (1982) ch 1

- ^ White (1982) p. 43-44

- ^ White (1982) ch 2

- ^ White (1982) pp. 44-67

- ^ White (1982 pp 69

- ^ His biographer says Warren was "The most visible and effective California public official advocating internment." White (1982) p. 71

- ^ John Aubrey Douglass, "Earl Warren's New Deal: Economic Transition, Postwar Planning, and Higher Education in California." Journal of Policy History 2000 12(4): 473-512

- ^ Daniel J. B. Mitchell, "Earl Warren's Fight for California's Freeways: Setting a Path for the Nation," Southern California Quarterly 2006 88(2): 205-238 34p.

- ^ It was not as payoff for campaign work, says White (1982) p. 148; but Henry J. Abraham, Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed. 1992) p 255 suggests Ike owed Warren some gratitude. Eisenhower said he owed Warren nothing.

- ^ Personal and confidential To Milton Stover Eisenhower, 9 October 1953. In The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, ed. L. Galambos and D. van Ee, (1996) doc. 460.

- ^ [www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/democracy/robes_warren.html]

- ^ White (1982) pp 159-61

- ^ MichaEl R. Belknap, The Supreme Court under Earl Warren, 1953-1969 (2005) pp. 13-14

- ^ Melvin I. Urofsky, "Warren, Earl" in Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 9, (1994) p 838

- ^ Lawrence S. Wrightsman, The psychology of the Supreme Court (2006) p 211; Priscilla Machado Zotti, Injustice for all: Mapp vs. Ohio and the Fourth Amendment (2005) p. 11

- ^ Melvin I. Urofsky, The Warren court: justices, rulings, and legacy (2001) p. 157

- ^ Lucas A. Powe, The Warren Court and American Politics (2000) pp 499-500

- ^ Melvin I. Urofsky The Warren court: justices, rulings, and legacy (2001) p xii, says "But sometimes it went too far, and the work of the Burger Court in part consisted of correcting those excesses." L. A. Scot Powe, The Warren court and American politics (2000): p 101, reports "a fear not only among conservatives but among moderates as well as some liberals that the Justices had gone too far in protecting individual rights and in so doing had moved into the legislative domain."

- ^ Powe (2000) ch 19

- ^ In later years Eisenhower remarked several times that making Warren the Chief Justice was a mistake. He probably had the criminal cases in mind, not Brown. See David. A. Nichols, Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution (2007) pp 91-93

- ^ Powe (2000)

- ^ See Smithsonian, “Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education’’

- ^ See, e.g., Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, Berea College v. Kentucky, Gong Lum v. Rice, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, and Sweatt v. Painter

- ^ For text see BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

- ^ Robert L. Carter, "The Warren Court and Desegregation," Michigan Law Review, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Dec., 1968), pp. 237-248 in JSTOR

- ^ Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (2001)

- ^ James A. Gazell, "One Man, One Vote: Its Long Germination," The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Sep., 1970), pp. 445-462 in JSTOR

- ^ See REYNOLDS v. SIMS, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)

- ^ Robert B. McKay, "Reapportionment: Success Story of the Warren Court." Michigan Law Review, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Dec., 1968), pp. 223-236 in JSTOR

- ^ See MIRANDA v. ARIZONA, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)

- ^ Ronald Kahn and Ken I. Kersch, eds. The Supreme Court and American Political Development (2006) online at p. 442

- ^ Thomas Sowell, The Vision of the Anointed: Self-congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy (1995) online at p. 26-29

- ^ See ENGEL v. VITALE, 370 U.S. 421 (1962)

- ^ See Griswold v. Connecticut (No. 496) 151 Conn. 544, 200 A.2d 479, reversed

- ^ Michal R. Belknap, The Supreme Court under Earl Warren, 1953-1969 (2005)

- ^ Artemus Ward, "An Extraconstitutional Arrangement: Lyndon Johnson and the Fall of the Warren Court" White House Studies 2002 2(2): 171-183

- ^ Stephen L. Wasby, "Civil Rights and the Supreme Court: A Return of the Past," National Political Science Review, July 1993, Vol. 4, pp 49-60

- ^ The Warren Commission Report: Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy by President's Commission on The Assassination (1964)

- ^ Newton (2006) pp 415-23, 431-42

- ^ Max Holland, "The key to the Warren report," American Heritage, Nov 95, Vol. 46 Issue 7, pp 50-59

- ^ Earl Warren was portrayed by real life New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison in JFK, the Oliver Stone film about the assassination and Garrison's investigation of it.

- ^ in Hail to the Chief: Earl Warren and the Supreme Court, 81 Mich. L. Rev. 922, 930 (1983).

- ^ Political Research Associates, "John Birch Society"

- ^ "Earl Warren (1891-1974)". Earl Warren College. Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Woodward, Bob (2005). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York, New York: Siomn & Schustler. p. 385. ISBN 0-7432-7402-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren inducted into California Hall of Fame, California Museum, Accessed 2007

- ^ "Notable Trees of Berkeley" (flash). Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA US President – R Primary Race – May 05, 1936

- ^ Our Campaigns – US President – R Primaries Race – Feb 01, 1936

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA Governor – R Primary Race – Aug 25, 1942

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA Governor – D Primary Race – Aug 25, 1942

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA Governor Race – Nov 03, 1942

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA US President – R Primary Race – May 16, 1944

- ^ Our Campaigns – US President – R Primaries Race – Feb 01, 1944

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA – Governor – R Primary Race – Jun 05, 1946

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA – Governor – D Primary Race – Jun 05, 1946

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA Governor Race – Nov 05, 1946

- ^ Our Campaigns – US President – R Primaries Race – Feb 01, 1948

- ^ Our Campaigns – US President – R Convention Race – Jun 21, 1948

- ^ Our Campaigns – US Vice President – R Convention Race – Jun 21, 1948

- ^ Our Campaigns – CA Governor Race – Nov 07, 1950

- ^ Our Campaigns – US President – R Primaries Race – Feb 01, 1952

- ^ "SNPP.com: "Itchy and Scratchy: The Movie" episode capsule". Retrieved 2011-07-03.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Belknap, Michael, The Supreme Court Under Earl Warren, 1953-1969 (2005), 406pp excerpt and text search

- Cray, Ed. Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren (1997), the most comprehensive biography; highly favorable; strong on politics excerpt and text search

- Horwitz, Morton J. The Warren Court and the Pursuit of Justice (1999) excerpt and text search

- Lewis, Anthony. "Earl Warren" in Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Volume: 4. (1997) pp 1373–1400; includes all members of the Warren Court. online edition

- Newton, Jim. Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made (2006), solid biography by journalist excerpt and text search

- Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (2001) online edition

- Powe, Lucas A.. The Warren Court and American Politics (2000) excerpt and text search

- Rawls, James J. "The Earl Warren Oral History Project: an Appraisal." Pacific Historical Review 1987 56(1): 87-97. Begun during the 1960s by the Bancroft Library's Regional Oral History Office, the collection includes more than 50 volumes of interviews recorded and transcribed during 1971-81, totaling about 12,000 pages.

- Scheiber, Harry N. Earl Warren and the Warren Court: The Legacy in American and Foreign Law (2006)

- Schwartz, Bernard. The Warren Court: A Retrospective (1996) excerpt and text search

- Schwartz, Bernard. "Chief Justice Earl Warren: Super Chief in Action." Journal of Supreme Court History 1998 (1): 112-132

- Time Magazine. "The Chief," Time Nov. 17, 1967

- Tushnet, Mark. The Warren Court in Historical and Political Perspective (1996) excerpt and text search

- Warren, Earl. The Memoirs of Earl Warren (1977), goes only to 1954

- Warren, Earl. The Public Papers of Chief Justice Earl Warren, ed. by Henry M. Christman; (1959), speeches and decisions, 1946-1958 online edition.*White, G. Edward. Earl Warren, a public life (1982) ISBN 0-19-503121-0, by a leading scholar

- Woodward, Robert and Armstrong, Scott. The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court (1979). ISBN 978-0-380-52183-8; ISBN 0-380-52183-0. ISBN 978-0-671-24110-0; ISBN 0-671-24110-9; ISBN 0-7432-7402-4; ISBN 978-0-7432-7402-9.

External links

- Earl Warren at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Oral History Interview with Earl Warren, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

- More information on Earl Warren and his Masonic Career.

- Earl Warren's Eulogy for John F. Kennedy

- "California 1946," (Dec 21, 1945). A speech by Earl Warren from the Commonwealth Club of California Records at the Hoover Institution Archives.

- "Earl Warren". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Earl Warren (April 11, 1952)" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1953-1954 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1955-1956 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1956-1957 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1957-1958 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1958-1962 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1962-1965 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1965-1967 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1967-1969 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- 1891 births

- 1974 deaths

- American military personnel of World War I

- American Protestants

- American people of Norwegian descent

- American people of Swedish descent

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- California Attorneys General

- California Republicans

- Chief Justices of the United States

- District attorneys

- Governors of California

- Members of the Warren Commission

- People from Bakersfield, California

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recess appointments

- Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Republican Party state governors of the United States

- United States Army officers

- United States federal judges appointed by Dwight D. Eisenhower

- United States presidential candidates, 1936

- United States presidential candidates, 1948

- United States presidential candidates, 1952

- United States vice-presidential candidates, 1948

- University of California, Berkeley alumni

- University of California, Berkeley School of Law alumni