Cyclocomputer

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

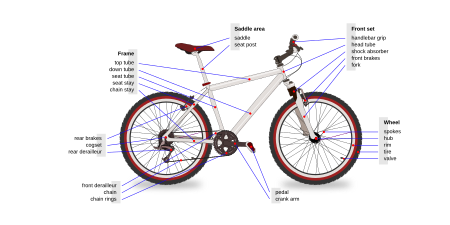

A cyclocomputer or cyclometer (obs.) is a device mounted on a bicycle that calculates and displays trip information, similar to the instruments in the dashboard of a car. The computer with display, or head unit, usually is attached to the handlebar for easy viewing.

History

In 1895 Curtis Hussey Veeder invented the Cyclometer.[1][2] The Cyclometer was a simple mechanical device that counted the number of rotations of a bicycle wheel.[3] A cable transmitted the number of rotations of the wheel to an analog odometer visible to the rider, which converted the wheel rotations into the number of miles traveled according to a predetermined formula. After founding the Veeder Manufacturing Company, Veeder promoted the Cyclometer with the slogan, It's Nice to Know How Far You Go.[4] The Cyclometer's success led to many other competing types of mechanical computing devices. Eventually, cyclometers were developed that could measure speed as well as distance traveled.

Modern Cyclocomputers

Basic operation

The head

A basic cyclocomputer may display the current speed, maximum speed, trip distance, trip time, total distance traveled, and the current time. More advanced models also may display altitude, incline (inclinometer), heart rate, power output (measured in watt) and temperature as well as offer additional functions such as average speed, pedaling cadence, a stopwatch and even GPS navigation. They have become useful accessories in bicycling as a sport and as a recreational activity.

The display is usually implemented with a liquid crystal display, and it may show one or more values at once. Many current models display one value, such as current speed, with large numbers, and another number that the user may select, such as time, distance, average speed, etc., with small numbers.

The head usually has one or more buttons that the user can push to switch the value(s) displayed, reset values such as time and trip distance, calibrate the unit, and on some units, turn on a back light for the display.

The wheel sensor

The older, traditional sensors have a magnet attached to a spoke of either the front or rear wheel. A sensor based either on the Hall effect, or on a magnetic reed switch, is attached to the fork or the rear of the frame. The sensor detects when the magnet passes once per rotation of the wheel. Alternatively, a sensor may be attached to the wheel hub. Distance is determined by counting the number of rotations, which translates into the number of wheel circumferences passed. Speed is calculated from distance against lapsed time period. The new sensors use a magnetic field, created by a magnet attached to a spoke, to determine an angle of wheel rotation for a fixed time of several milliseconds. The sensor is mounted on a quick release and works like a compass pointing to a magnet like a north pole arrow. Magnetic field sensors provide higher accuracy of speed and acceleration measurement.[citation needed]

The cadence sensor

To measure cadence, a magnet is mounted to the crankarm, and a sensor mounted to the frame.

Transmission

Some models use a wired connection between the sensor and the head unit. Other cyclocomputers, e.g. those used by competitive cyclists, transmit the data wirelessly from the sensor/transmitter to the head unit.

Calibration

Once a new computer is installed, it usually requires proper configuration. This normally includes selecting distance units (kilometers vs. miles) and the circumference of the wheel. Since the sensor measures wheel rotation, different wheel sizes will translate to different measures of speed and distance for a given number of rotations.

For true accuracy, however, the bicycle (with the set cyclocomputer) must be ridden by the intended rider over an accurately measured distance. The computer's reading is then compared with the known distance and any necessary corrections made.

Additional information

Besides variables calculated from the rotating wheels or crank, cyclocomputers can display other information.

Gearing

For integrated shifters on racing bicycles, the gear can be read by the computer: Shimano's Flight Deck and Campagnolo's ErgoBrain work with their respective systems to detect the gearing. This allows indirect measurement of cadence. These systems do not have sensors on the crankset or cassette to determine what gear the bicycle is in. They work exclusively with the shifters, which may result in misleading information. Instead of knowing what gear the bicycle is in, they rely on sensing when the cyclist changes gears using sensors in the shifters. If the gear change doesn't actually happen, or the computer's sensors are too sensitive (eg: when braking with STI-style shifters), the information displayed is not accurate.

Performance

With additional sensors, other performance measurements are available:

- A heart rate monitor can be integrated into the computer, using a chest strap sensor.

- A power meter measures power output in watts, using a torque sensor in the bottom bracket or rear hub.

Environment

Some models also have sensors built into the head that measure and display environmental parameters such as temperature and altitude.

Cyclist power measurement

Some more sophisticated models are able to measure the rider's power in terms of watts. These units incorporate elements that measure torque at the crank, or rear wheel hub,[5] or tension on the chain.[6] This technology began in the late 1980s. (See Team Strawberry for the early development and testing stages of this technology.)

References

- ^ The Horseless Age, New York: The Horseless Age Company, Volume 40, No. 1, (1917), p. 58

- ^ Robert Asher (2003). "Connecticut Inventors". Connecticut Humanities Council. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ^ Veeder-Root, Inc., Veeder Root History

- ^ Veeder-Root Inc., Veeder-Root History

- ^ "Power Tap by Grabar Inc". Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ "Polar S-710". Retrieved 2009-05-15.