Leopold II of Belgium

| Leopold II | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of the Belgians | |

| Reign | 17 December 1865 – 17 December 1909 |

| Predecessor | Leopold I |

| Successor | Albert I |

| Born | 9 April 1835 Brussels, Belgium |

| Died | 17 December 1909 (aged 74) Laeken/Laken, Belgium |

| Spouse | Marie Henriette of Austria |

| Issue | Louise Marie, Princess of Kohary Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant Stéphanie, Crown Princess of Austria Clémentine, Princess Napoléon |

| House | House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Father | Leopold I |

| Mother | Louise-Marie of France |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Leopold II (Template:Lang-fr, Template:Lang-nl) (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the King of the Belgians, and is chiefly remembered for the founding and brutal exploitation of the Congo Free State. Born in Brussels the second (but eldest surviving) son of Leopold I and Louise-Marie of Orléans, he succeeded his father to the throne on 17 December 1865 and remained king until his death. Due to his many female lovers, he was also called "The Belgian Bull".[citation needed]

Leopold was the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State, a private project undertaken on his own behalf. He used Henry Morton Stanley to help him lay claim to the Congo, an area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the colonial nations of Europe committed the Congo Free State to improving the lives of the native inhabitants. From the beginning, however, Leopold essentially ignored these conditions and ran the Congo using a mercenary force, for his personal gain.

Leopold extracted a fortune from the Congo, initially by the collection of ivory, and after a rise in the price of rubber in the 1890s, by forcing the population to collect sap from rubber plants. Villages were required to meet quotas on rubber collections, and individuals' hands were cut off if they didn't meet the requirements. His regime was responsible for the death of an estimated 2 to 15 million Congolese. This became one of the most infamous international scandals of the early 20th century, and Leopold was ultimately forced to relinquish control of it to the government of Belgium.

Biography

Early life

Leopold was born in Brussels on 9 April 1835. He was the second child of the reigning Belgian monarch, Leopold I, and his second wife, Louise, the daughter of King Louis Philippe of France. His elder brother had died a few months after his birth in 1834, and thus Leopold was heir to the throne. When he was 9 years old, Leopold received the title of Duke of Brabant.

Early political career

Leopold's public career began in 1855, when he became a member of the Belgian Senate. That same year Leopold began to urge Belgium's acquisition of colonies. In 1853 he married Marie Henriette, daughter of the Austrian archduke Joseph, in Brussels on 22 August 1853. Four children were born of this marriage; three were daughters, and the only son, Leopold, died when he was 9 years old.

Reign

In 1865 Leopold became king. His reign was marked by a number of major political developments. The Liberals governed Belgium from 1857 to 1880 and during their final year in power legislated the Frère-Orban Law of 1879. This law created free, secular, compulsory primary schools supported by the state and withdrew all state support from Roman Catholic primary schools. In 1880 the Catholic Party obtained a parliamentary majority and 4 years later restored state support to Catholic schools. In 1885 various socialist and social democratic groups drew together and formed the Labour Party. Increasing social unrest and the rise of the Labour Party forced the adoption of universal male suffrage in 1893. In Belgian domestic politics, Leopold emphasized military defense as the basis of neutrality, but he was unable to obtain a universal conscription law until on his death bed.

Obtaining the Congo Free State

Leopold fervently believed that overseas colonies were the key to a country's greatness, and he worked tirelessly to acquire colonial territory for Belgium. Leopold eventually began trying to acquire a colony in his private capacity as an ordinary citizen. The Belgian government lent him money for this venture.

In 1866, Leopold instructed the Belgian ambassador in Madrid to speak to Queen Isabella II of Spain about ceding the Philippines to Belgium. However, knowing the situation fully, the ambassador did nothing. Leopold quickly replaced the ambassador with a more sympathetic individual to carry out his plan.[1]

In 1868, when Isabella II was deposed as Queen of Spain, Leopold attempted to take advantage of his original plan to acquire the Philippines. But without funds, he was unsuccessful. Leopold then devised another unsuccessful plan to establish the Philippines as an independent state, which could then be ruled by a Belgian. Because both of these plans had failed, Leopold shifted his aspirations of colonization to Africa.[1]

After numerous unsuccessful schemes to acquire colonies in Africa and Asia, in 1876 Leopold organized a private holding company disguised as an international scientific and philanthropic association, which he called the International African Society, or the International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of the Congo. In 1878, under the auspices of the holding company, he hired the famous explorer Henry Stanley to explore and establish a colony in the Congo region.[2] Much diplomatic maneuvering resulted in the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 regarding African affairs, at which representatives of fourteen European countries and the United States recognized Leopold as sovereign of most of the area to which he and Stanley had laid claim. On 5 February 1885, the Congo Free State was established under Leopold II's personal rule, an area 76 times larger than Belgium, which Leopold was free to control through his private army, the Force Publique.

Exploitation and atrocities

Leopold then amassed a huge personal fortune by exploiting the Congo. The first economic focus of the colony was ivory, but this did not yield the expected levels of revenue. When the global demand for rubber exploded, attention shifted to the labor-intensive collection of sap from rubber plants. Abandoning the promises of the Berlin Conference in the late 1890s, the Free State government restricted foreign access and extorted forced labor from the natives. Abuses, especially in the rubber industry, included the effective enslavement of the native population, beatings, widespread killing, and frequent mutilation when the production quotas were not met. Missionary John Harris of Baringa, for example, was so shocked by what he had come across that he wrote to Leopold's chief agent in the Congo saying: "I have just returned from a journey inland to the village of Insongo Mboyo. The abject misery and utter abandon is positively indescribable. I was so moved, Your Excellency, by the people's stories that I took the liberty of promising them that in future you will only kill them for crimes they commit."[3]

Estimates of the death toll range from two million to fifteen million.[4][5][6] Determining precisely how many people died is next to impossible as accurate records were not kept. Louis and Stengers state that population figures at the start of Leopold's control are only "wild guesses", while E. D. Morel's attempt and others at coming to a figure for population losses were "but figments of the imagination".[7]

Adam Hochschild devotes a chapter of his book, King Leopold's Ghost, to the problem of estimating the death toll. He cites several recent lines of investigation, by anthropologist Jan Vansina and others, examining local sources from police records, religious records, oral traditions, genealogies, personal diaries, and "many others", which generally agree with the assessment of the 1919 Belgian government commission: roughly half the population perished during the Free State period. Since the first official census by the Belgian authorities in 1924 put the population at about 10 million, that implies a rough estimate of 10 million dead.[8]

Smallpox and sleeping sickness also devastated the disrupted population.[9] By 1896 the sleeping sickness had killed up to 5,000 Africans in the village of Lukolela on the Congo River. The mortality figures were collected through the efforts of Roger Casement, who found, for example, only 600 survivors of the disease in Lukolela in 1903.[10]

Criticism of his rule

Reports of outrageous exploitation and widespread human rights abuses led to international outcry in the early 1900s leading to a widespread war of words. The campaign to examine Leopold's regime, led by British diplomat Roger Casement and former shipping clerk E. D. Morel under the auspices of the Congo Reform Association, became the first mass human rights movement.[11] Supporters included American writer Mark Twain, who wrote a stinging political satire entitled King Leopold's Soliloquy, in which the King supposedly argues that bringing Christianity to the country outweighs a little starvation. Rubber gatherers were tortured, maimed and slaughtered until the start of the 20th century, when the Western world forced Brussels to call a halt.[12]

Leopold's rule was subject to severe criticism, especially from British sources. Arthur Conan Doyle also criticised the 'rubber regime' in his 1908 work The Crime of the Congo, written to aid the work of the Congo Reform Association. Doyle contrasted Leopold's rule to the British rule of Nigeria, arguing decency required that those who ruled primitive peoples to be concerned first with their uplift, not how much could be extracted from them. It should be noted that, as Hochschild describes in King Leopold's Ghost, many of Leopold's policies were adopted from Dutch practices in the East Indies, and similar methods were employed to some degree by Germany, France and Portugal where natural rubber occurred in their colonies.

Relinquishment of the Congo

Criticism from both Social Catholics and the Labor party caused the Belgian parliament to compel the King to cede the Congo Free State to Belgium in 1908. The Congo Free State was transformed into a Belgian colony known as the Belgian Congo under parliamentary control. It later became, successively, the Republic of the Congo, Zaire (under Mobutu Sese Seko), and currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC, not to be confused with Republic of the Congo formerly owned by France.

Attempted assassination

On 15 November 1902, Italian anarchist Gennaro Rubino attempted to assassinate Leopold, who was riding in a royal cortege from a ceremony in memory of his recently-deceased wife, Marie Henriette. After Leopold's carriage passed, Rubino fired three shots at the King; the shots missed Leopold and Rubino was immediately arrested.

Death

On 17 December 1909, Leopold II died at Laeken, and the Belgian crown passed to Albert, the son of Leopold's brother, Philip, Count of Flanders. He was interred in the royal vault at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken in Brussels.

Family

Leopold II was the brother of Empress Carlota of Mexico, and among his first cousins were both Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and her husband Prince Albert, and King Fernando II of Portugal.

He had four children with Queen Marie-Henriette:

- Louise-Marie Amélie, born in Brussels on 18 February 1858, and died at Wiesbaden on 1 March 1924. She married Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

- Léopold Ferdinand Elie Victor Albert Marie, Count of Hainaut (as eldest son of the heir apparent), later Duke of Brabant (as heir apparent), born at Laeken/Laken on 12 June 1859, and died at Laken on 22 January 1869, from pneumonia, after falling into a pond.

- Stéphanie Clotilde Louise Herminie Marie Charlotte, born at Laken on 11 May 1864, and died at the Archabbey of Pannonhalma in Győr-Moson-Sopron, Hungary, on 23 August 1945. She married (1) Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria and then (2) Elemér Edmund Graf Lónyay de Nagy-Lónya et Vásáros-Namény (created, in 1917, Prince Lónyay de Nagy-Lónya et Vásáros-Namény).

- Clémentine, born at Laken on 30 July 1872, and died at Nice on 8 March 1955. She married Prince Napoléon Victor Jérôme Frédéric Bonaparte (1862–1926), head of the Bonaparte family.

Leopold was also the father of two illegitimate sons through Caroline Lacroix, later adopted in 1910 by Lacroix's second husband, Antoine Durrieux:[13]

- Lucien Philippe Marie Antoine (9 February 1906 – 1984), duke of Tervuren[13]

- Philippe Henri Marie François (16 October 1907 – 21 August 1914), count of Ravenstein[13]

Legacy

Though unpopular at the end of his reign—his funeral cortege was booed—Leopold II is remembered today by many Belgians as the "Builder King" (Koning-Bouwer in Dutch, le Roi-Bâtisseur in French) because he commissioned a great number of buildings and urban projects, mainly in Brussels, Ostend and Antwerp.[citation needed] These buildings include the Royal Glasshouses in the grounds of the Palace at Laken, the Japanese Tower, the Chinese Pavilion, the Musée du Congo (now called the Royal Museum for Central Africa), and their surrounding park in Tervuren, the Cinquantenaire in Brussels, and the 1895-1905 Antwerpen-Centraal railway station. He also built an important country estate in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat on the French Riviera, including the Villa des Cèdres, which is now a botanical garden. These were all built using the profits from the Congo. In 1900, he created the Royal Trust, by which means he donated most of his property to the Belgian nation.

Leopold II is still a controversial figure in the Democratic Republic of Congo. His statue in the capital, Kinshasa, was removed after independence. Congolese culture minister Christoph Muzungu decided to reinstate the statue in 2005, pointing out the sense of liberating progress that had marked the beginning of the Free State and arguing that people should see the positive aspects of the king as well as the negative; but just hours after the six-metre (20 ft) statue was erected in the middle of a roundabout near Kinshasa's central station, it was taken down again without explanation. The Congo continues, however, to use a variation of the Free State flag, which it adopted after dropping the name and flag of Zaire.

After the King transferred his private colony to Belgium, there was, as Adam Hochschild puts it in King Leopold's Ghost, a "Great Forgetting".[citation needed] Hochschild records that, on his visit to the colonial Royal Museum for Central Africa in the 1990s, there was no mention of the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State, despite the museum's large collection of colonial objects.[citation needed] Another example of this "Great Forgetting" may be found on the boardwalk of Blankenberge, a popular coastal resort, where a monument shows a colonialist bringing "civilization" to the black child at his feet.[citation needed] On the beach in Oostend is a 1931 sculptural monument to Leopold II, showing Leopold and grateful Ostend fishermen and Congolese. The inscription accompanying the Congolese group mentions The gratitude of the Congolese to Leopold II for having liberated them from slavery under the Arabs. In 2004, an activist group cut off the hand of the leftmost Congolese bronze figure, in protest against the Congo atrocities.[14][15]

Trivia

- Leopold II was selected as a main motif for the recent 12.50 euro Leopold II commemorative coin minted in 2007. The obverse shows his portrait facing right.

- Leopold II also engaged in a religious ceremony with Blanche Zélia Joséphine Delacroix, also known as Caroline Lacroix, a prostitute, on 14 December 1909, with no validity under Belgian law, at the Pavilion of Palms, Royal Palace of Laken, in Brussels, five days before his death. The priest of Laeken Cooreman performed the ceremony.[13][16]

- He was the 973rd Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Austria, the 748th Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1866 and the 69th and 321st Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword.

| Styles of King Leopold II of the Belgians | |

|---|---|

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sire |

See also

-

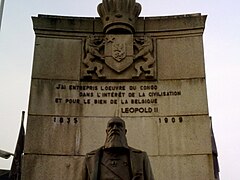

Leopold II horseback riding statue, Regent place, Brussels.

-

Leopold II with the coat of arms of the Belgian Congo in Ghent, Belgium.

Ancestry

References

- ^ a b Ocampo, Ambeth (2009). Looking Back. Anvil Publishing. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-971-27-2336-0.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam: King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Mariner Books, 1998. p. 62. ISBN 0-330-49233-0.

- ^ Mark Dummett (Feb 24 2004), King Leopold's legacy of DR Congo violence, BBC, retrieved 1 December 2011

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "web" ignored (help) - ^ The River Congo: The Discovery, Exploration and Exploitation of the World's Most Dramatic Rivers," Harper & Row, (1977). ISBN Forbath, Peter, p. 278.

- ^ Fredric Wertham A Sign For Cain: An Exploration of Human Violence (1968), Adam Hochschild King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1998; new edition, 2006).

- ^ "War statistics".

- ^ Wm. Roger Louis and Jean Stengers: E.D. Morel's History of the Congo Reform Movement, pp. 252–7.

- ^ Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost, Chapter 15, "A Reckoning".

- ^ "The 'Leopold II' concession system exported to French Congo with as example the Mpoko Company" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ^ "Le rapport Casement annoté par A. Schorochoff" (PDF). Posted at the website for the Royal Union for Overseas Colonies, http://www.urome.be.

{{cite web}}: External link in|location= - ^ Dummett, Mark (24 February 2004). "Africa". News. BBC. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Time". 16 May 1955. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Le Petit Gotha"

- ^ Pieter De Vos. "Sikitiko" (in Dutch). Retrieved 2012-08-13.

De dank der Congolezen aan Leopold II om hen te hebben bevrijd van de slavernij onder de Arabieren (1:10)

- ^ "Leopold II krijgt zijn hand terug als Oostende zwicht" (in Dutch). 2004-06-22. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ http://pages.prodigy.net/ptheroff/gotha/belgium.html

Bibliography

- Ascherson, Neal: The King Incorporated, Allen & Unwin, 1963. ISBN 1-86207-290-6 (1999 Granta edition).

- Hochschild, Adam: King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Mariner Books, 1998. ISBN 0-330-49233-0.

- Petringa, Maria: Brazza, A Life for Africa, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Wm. Roger Louis and Jean Stengers: E.D. Morel's History of the Congo Reform Movement, Clarendon Press Oxford, 1968.

- Ó Síocháin, Séamas and Michael O’Sullivan, eds: The Eyes of Another Race: Roger Casement's Congo Report and 1903 Diary. University College Dublin Press, 2004. ISBN 1-900621-99-1.

- Ó Síocháin, Séamas: Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 2008.

- Roes, Aldwin, Towards a History of Mass Violence in the Etat Indépendant du Congo, 1885-1908, http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/74340/2/roesAW2.pdf, South African Historical Journal, 62 (4). pp. 634-670, 2010.

External links

- Official biography from the Belgian Royal Family website

- "The Political Economy of Power" Interview with political scientist Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, with an extended discussion of Leopold II halfway through

- Interview with King Leopold II Publishers' Press, 1906

- Mass crimes against humanity in the Congo Free State

- Congo: White king, red rubber, black death A 2003 documentary by Peter Bate on Leopold II and the Congo

- Belgian royal princes

- Belgian monarchs

- Dukes of Brabant

- House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Belgium)

- Attempted assassination survivors

- People from Brussels

- 1835 births

- 1909 deaths

- Deaths from cerebral hemorrhage

- 19th-century monarchs in Europe

- 19th-century Belgian people

- Burials at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken

- Grand Cordons of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the African Star

- Grand Crosses of the Royal Order of the Lion

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown (Belgium)

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Leopold II

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Recipients of the Order of the Black Eagle

- Extra Knights Companion of the Garter

- Knights of the Order of the Most Holy Annunciation

- Congo Free State