Semar Gugat

| Semar Gugat | |

|---|---|

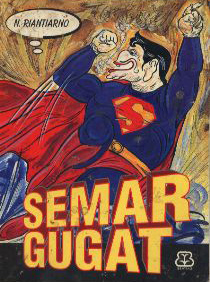

Cover, Bentang Budaya edition | |

| Written by | Nano Riantiarno |

| Characters | |

| Date premiered | November 25, 1995 |

| Place premiered | Graha Bakti Budaya, Taman Ismail Marzuki, Jakarta |

| Original language | Indonesian |

Semar Gugat (Indonesian for Semar Accuses) is a stage play written by Nano Riantiarno for his troupe Teater Koma. It follows the traditional wayang character Semar as he attempts— and fails— to take revenge against Arjuna and Srikandi for humiliating him by cutting off a lock of his hair while they are under the influence of the demon queen Durga. Completed in mid-1995, the play consists of 559 lines of dialogue spread through 30 scenes. Semar Gugat has been read as a critique of the New Order government under president Suharto. It was first performed on 25 November 1995 after the government withheld permission for several months. After Teater Koma gave an initial two-week run, it was adapted by various amateur groups. In 1998 Riantiarno won a S.E.A. Write Award for the work.

Plot

The kingdom of Amarta is preparing for the wedding of Arjuna and Srikandi. The Punakawans—Semar, his wife Sutiragen, and their children Gareng, Petruk, and Bagong—prepare to attend the ceremony.

However, the bride-to-be is fraught with doubt. Arjuna is already well known as a womanizer and has been with an untold number of women. She decides to test Arjuna's love by giving him a test. At this moment, Durga, the queen of demons, chooses to possess her body and, controlling Srikandi's voice, demands to see Arjuna even though tradition forbids it. With the support of Arjuna's two other wives, Sumbadra and Larasasti, she succeeds in meeting Arjuna and tells him to provide a lock (kuncur) of Semar's hair as proof of his devotion. Arjuna reluctantly does the deed and the ceremony goes as scheduled. However, Semar is unable to accept the humiliation, stating that not even gods dare touch his head. The family does not attend Arjuna's wedding, despite being palace servants, and Semar cries at home for the remainder of the day. Meanwhile, Arjuna's brothers, including King Yudistira, leave the kingdom to meditate; Arjuna is left to rule over Amarta.

Semar decides that he has had enough humiliation; although he is very powerful, he feels constantly abused by humans and gods. With his favourite son Bagong he goes to the palace of the gods in Kayangan. However, only Semar is admitted; Bagong is chased off by two guards. Semar speaks to the gods Batara Guru and Batara Narada and asks to regain the handsome face he had once had. This they give him, using plastic surgery. Semar is made human and given his own kingdom, Simpang Bawana Nuranitis Asri. Semar changes his name to Prabu Sanggadonya Lukanurani. Although he has become leader of his own kingdom, Semar is unable to find happiness. His wife, not believing that he is Semar, leaves him; only his sons Petruk and Gareng join him. They begin building the kingdom, but are displeased to find that all of its riches are not enough to ensure harmony.

Meanwhile, in Amarta, Arjuna's leadership is causing the populace to feel miserable. Under the influence of Srikandi (who remains possessed by Durga), Arjuna focuses on economic development and increases the number of imports. He establishes monopolies on common commodities hoping to control the population and uses popular culture to promote a sense of selfless nationalism. Much of the disillusioned populace emigrates from Amarta, while others send extensive letters of protest to the palace. Those who remain are later possessed by demons under Durga's leadership, becoming prisoners in their own bodies.

In Simpang Bawana Nuranitis Asri, Larasati and Sumbadra—who have lost favour in Amarta—arrive. They meet with two warriors from Amarta, Sumbadra's son Abimanyu and his cousin Gatotkaca, who have come to tell Semar of Amarta's suffering. Unable to accept the people's suffering, Semar goes to his former homeland and challenges Arjuna and Srikandi, whom he realises has been possessed. When Semar tries to use his sacred flatulence known as "Ajian The White Kentuts", said to be capable of causing "whirlwinds, tornadoes, floods, earthquakes, [and] volcanic eruptions",[a][1] nothing happens. Durga laughs at Semar's impotence and lets him live, considering it the greatest humiliation possible. Petruk and Gareng join Durga, leaving Semar alone.

Description

Semar Gugat is a stage play in 30 scenes. It also features an untitled opening song[2] and a closing song entitled "Nyanyi Sunyi Jagat Raya" ("The Universe's Silent Song");[3] other songs, some untitled, are interspersed in the play proper. The story features 25 speaking roles, with an unspecified number of unnamed mute characters.[4] Its 559 lines of dialogue is focused mostly on eight characters: Semar, Gareng, Petruk, Bagong, Durga, Kalika (Durga's minion), and Srikandi.[5]

The script was written by Nano Riantiarno, leader of Teater Koma, and completed in June 1995.[6] It was the 78th production for Teater Koma.[7]

Themes and style

Semar is a character in traditional Javanese puppetry (wayang), depicted as a god who has come to Earth to serve human kings. Although he had been used by President Suharto of the New Order as symbolic of the regime,[8] Semar is traditionally considered representative of the common people (wong cilik),[9] as are the other Punakawans.[8] As such, theologian J. B. Banawiratma surmises that the play is representative of the common people accusing the forces in power, be they internal or external. He writes that the power which is challenged is not that which is used for the good of the people, but power which is abused for a leader's self-interest. He further writes that the demon Durga serves as a personification of this abusive power.[8]

Muhammad Ismail Nasution of the State University of Padang concurs, suggesting that the play is a criticism of the New Order government. He notes that dialogue criticising the social realities of New Order Indonesia is generally spoken by Semar's sons and encompasses the business practices, educational policies, nepotism, and inequality found in New Order Indonesia.[10] Quoting a line from Semar, in which he discounts his children's suggestion that Semar lead protests, Nasution also notes criticism of the youths who would demonstrate against the New Order, depicting them as being easily manipulated by agents provocateur and often needlessly destroying material goods.[10]

H. Sujiwo Tejo of Kompas writes that the performance used more modern story telling techniques, noting that changes between scenes were more stylised and quicker than in traditional wayang. He also notes influences of modern dance, another departure from traditional theatre.[9]

Performance

After Riantiarno completed writing Semar Gugat, the New Order government—which required stage plays to receive formal permission before performances could be held— held up production. Generally this was straightforward, but some playwrights reportedly faced more stringent criteria.[11] Riantiarno, who had previously been highly critical of the government in depicting prostitutes, transsexuals, and corrupt officials in Opera Kecoa (The Cockroach Opera),[12] was one such writer; others included Rendra and Guruh Sukarnoputra.[11] The government only formally granted permission for the play to be performed on 24 November 1995.[9] Owing to debate over the censorship of stage plays by the government, including Semar Gugat, in 1996 the government formally rescinded the requirement; social commentators, however, remained skeptical.[13]

Semar Gugat was first performed at 800-seat Graha Bakti Budaya in Taman Ismail Marzuki, Jakarta, the day after permission was granted, by Riantiarno's Teater Koma. Tickets for the first two performances, each running three hours, sold out in advance; Tejo noted that most of the audience were not regular theatre-goers. The initial two-week run was produced by Nano's wife Ratna, with its choreography handled by Sentot S and music directed by Idrus Madani. Semar was portrayed by Budi Ros,[9] while other roles were taken by Dudung Hadi, O'han Adiputra, Budi Suryadi, Ratna Riantiarno, Derias Pribadi, and Asmin Timbil.[7] For his work on Semar Gugat, in 1998 Nano Riantiarno received the S.E.A. Write Award from the government of Thailand.[14]

A book version of the script was published in November 1995 by Bentang Budaya in Yogyakarta, with cover design by Si Ong.[15] The play has continued to be performed by various amateur groups.

Explanatory notes

- ^ Original: "... lesus, angin puyuh, banjir bandang, gempa bumi, [dan] gunung-gunung meletus."

References

- ^ Riantiarno 1995, p. 99.

- ^ Riantiarno 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Riantiarno 1995, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Riantiarno 1995, pp. ix–x.

- ^ Nasution 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Riantiarno 1995, p. 109.

- ^ a b Teater Koma 1995, Pamphlet.

- ^ a b c Banawiratma 1999, pp. 561–563.

- ^ a b c d Tejo 1995, Angin Litsus dari Semar.

- ^ a b Nasution 2009, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Bodden 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Brown 2007, p. 1136.

- ^ Bodden 2010, p. 305.

- ^ JCG, Nano Riantiarno.

- ^ Riantiarno 1995, p. iv.

Works cited

- Tejo, H Sujiwo (26 November 1995). "Angin Litsus dari Semar". Kompas (in Indonesian).

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Banawiratma, J.B. (1999). Darmaputera, Eka; Suleeman, F.; Sutama, Adji Ageng; Rajendra, A (eds.). Kebudayaan Jawa dan Teologi Pembebasan (in Indonesian). Jakarta: BPK Gunung Mulia. pp. 555–570.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Bodden, Michael (2010). Resistance on the National Stage: Modern Theater and Politics in Late New Order Indonesia. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-469-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Ian Jarvis (2007). "Riantiarno, Nano (1949 - )". In Cody, Gabrielle (ed.). The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama. Vol. 2. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14424-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Nano Riantiarno". Encyclopedia of Jakarta. Jakarta City Government. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Nasution, Muhammad Ismail (2009). ""Semar Gugat" dalam Telaah Tokoh: Sebuah Model Pemaknaan Naskah Drama". Bahasa dan Seni (in Indonesian). 10 (1). State University of Padang: 43–53. ISSN 0854-8277.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - "Pamphlet". Teater Koma. 1995. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Riantiarno, Nano (1995). Semar Gugat (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Bentang Budaya. OCLC 298049518.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)