Logophoricity

The term logophor was introduced by Claude Hagège (1974) in order to distinguish logophoric pronouns from indirect reflexive pronouns. In particular, Hagège argues that logophors are a distinct class of pronouns which refer to the source of indirect discourse: the individual whose perspective is being communicated, rather than the speaker who is relaying this information. George N. Clements (1975) expanded upon this analysis, arguing that indirect reflexives serve the same function as logophoric pronouns, even though indirect reflexives do not exhibit a distinct form from their non-logophoric counterparts, whereas logophoric pronouns (as Hagège defined them) do (Reuland 2006, p. 3). For example, the Latin indirect reflexive pronoun sibi may be said to have two grammatical functions (logophoric and reflexive), but just one form (Clements 1975). More recent analyses of logophoricity are in line with this account, under which indirect reflexives are considered to be logophors, in addition to those pronouns with a special logophoric form (Reuland 2006, p. 3).

Clements also extended the concept of logophoricity beyond Hagège's initial typology, addressing syntactic and semantic properties of logophoric pronouns, as well. (Reuland 2006, p. 3). He posited three distinctive properties of logophors:

- Logophoric pronouns are discourse-bound: they may only occur in a context in which the perspective of an individual other than the speaker's is being reported.

- The antecedent of the logophoric pronoun must not occur in the same clause in which the indirect speech is introduced.

- The antecdent specifies which individual's (or individuals') perspective is being reported.

These conditions are for the most part semantic in nature, though Clements also claimed that there are additional syntactic factors which may play a role when semantic conditions are not met, yet logophoric pronouns are still present. In Ewe, for example, logophoric pronouns may only occur in clauses which are headed by the complementizer "be" (which designates a reportive context in this language), and may only have a second- or third-person antecedent (first-person antecedents are prohibited). Other languages impose different conditions on the occurrence of logophors, which leads Clements to conclude that there are no universal syntactic constraints which must be satisfied by logophoric forms.

Logophoric Typology

Logophoric Affixes

The simplest form of a logophoric affix is a system called logophoric cross referencing. This is when a distinct affix is used to specify logophoric cases (Cunrow 2002). For example in Akɔɔse, a language spoken in Nigeria, the prefix mə attaches to the verb to indicate that the pronoun is self-referencing.

a. à-hɔbé ǎ á-kàg he-said RP he-should.go 'He said that he (someone else) should go' b. à-hɔbé ǎ mə-kàg he-said RP LOG-should.go 'He said that he (himself) should go' (Hedinger 1984:95)

It is important to note that not all cross-referencing utilizes the same properties. In Akɔɔse cross-referencing can only occur when the matrix subject is second or third person singular, not in plural or first person cases (Cunrow 2002). However any language that uses a logophoric cross-referencing system will always use it for singular referents. (Cunrow 2002:4)

Another manifestation of logophoric affixes is the logophoric verbal affix, or a logophoric affix that attaches to the verb. Unlike logophoric pronouns and the cross-referencing system, the logophoric verbal suffix is not otherwise integrated into a system that marks person (Cunrow 2002:11). In contrast with cross-referencing, verbal affixes are not obligatory for singular second person referents. Unlike most other types of logophoricity, verbal affixes may also be used in first person case, where generally this use is unpreferred. The verbal affix may also lead to ambiguity unlike most other types of logophoricity, as since it attaches to the verb and not to the subject, or a co-reffering pronoun, it only indicates that some unspecified item is coreferential to the matrix subject (Cunrow 2002:12). The language generally used to demonstrate logophoric verbal affixes is Gokana.

Gokana

Gokana is a language of the Benue-Congo system. It uses the verbal suffix -èè, with several different phonological variations to indicate logophoricity (Cunrow 2002:10).This can be seen in the example below.

?. aè kɔ aè dɔ he said he fell 'Hei said that hej fell ?. aè kɔ aè divèè e he said he fell-LOG 'Hei said that hei fell (Hyman & Comrie 1981:20)

The above example also shows that in Gokana the verbal affix contrasts with its own absence as opposed to contrasting with another affix or pronoun. Because of this, the verbal affix gives no indication of person. As mentioned above, logophoric verbal affixes can lead to ambiguities. This is demonstrated in a Gokana example below.

?. lébàreè kɔ aè dɔ-ɛ Lebare said he hit-LOG him 'Lebarei said hei hit himj/ Lebarei said hej hit himi (Hyman & Comrie 1981:24)

Logophoric Pronouns

Ewe

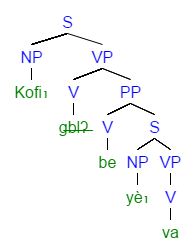

Ewe is a language of the Niger-Congo family which exhibits formally distinct logophoric pronouns. For example, the third person singular pronoun yè is used only in contexts in which the perspective of an individual other than the speaker is being represented. These special forms are a means of unambiguously identifying the nominal co-referent in a given sentence:

c. Tsali gblʔ na-e be ye-e dyi yè gake yè-kpe dyi. Tsali say to-Pron that Pron beget LOG but LOG be victor ‘Tsaliii told himj (i.e., his father) that hej begot himi but hei was the victor.’ (Clements 1975:152)

Notably, logophoric pronouns such as yè may occur at any level of embedding within the same sentence, and in fact, the antecedent with which it has co-referent relation need not be in the same sentence. The semantic condition imposed on the use of these logophors is that the context in which they appear must be reflective of another individual's perception, and not the speaker's subjective account of the linguistic content being transmitted. However, a purely semantic account is insufficient in determining where logophoric pronouns may appear. More specifically, even when the semantic conditions which license the use of logophors are satisfied, they may not appear in grammatical sentences. Clements demonstrates that these forms may only be introduced by clauses head by the complementizer "be". In Ewe, this word has the function of designating clauses in which the feelings, thoughts, and perspective of an individual other than the speaker is being communicated. Thus, although it is primarily the discursive context which licenses the use of logophoric pronouns in Ewe, syntactic restrictions also play a role in the grammaticality of indirect discourse.

Wan

In Wan, a language spoken primarily in the Ivory Coast, logophoric pronouns ɓā (singular) and mɔ̰̄ (plural) are used to indicate the speech of those who are introduced in the preceding clause (Nikitina 2012).

d. ɓé à nɔ̠̀ ɓé ɓā ɓé gōmɔ̠̄

then 3SG wife said LOG.SG that.one understood

'And his wifei said shei had understood that.'

e. yrā̠mū é gé mɔ̰̄ súglù é lɔ̄

children DEF said LOG.PL manioc DEF ate

'The childreni said theyi had eaten the manioc.' (Nikitina 2012:283)

These pronouns can take the same syntactic positions as personal pronouns (e.g. subjects, objects, possessors, etc.). They appear with verbs that have to do with mental and psychological activities and states; most often, they are used during speech reports. However, they cannot refer in any way to the current speaker (i.e. first person cannot be encoded with logophoricity). In casual conversation, using perfect form when speaking of past speech is often associated with logophoricity, as it implies that the event is more relevant to the current speech report (Nikitina 2012).

If in a case the speaker participates in the reported situation, their voice may be ambiguous as they may be confused with the voices of other characters in the discourse. Ambiguity with logophors also arise from reports where someone is reporting character A's report on character B's discourse. This is known as a "nested report".

f. è gé kólì má̰, klá̰ gé dóō ɓāā nɛ̰́ kpái gā ɔ̄ŋ́ kpū wiá ɓā lāgá 3SG said lie be hyena said QUOT LOG.SG.ALN child exact went wood piece enter LOG.SG mouth 'Hei said: It's not true. Hyenaj said myi,LOG own child went to enter a piece of wood in hisj,LOG mouth.' (Alternative interpretation: 'Hisj,LOG own child went to enter a piece of wood in myi,LOG mouth.') (Nikitina 2012:293)

Here, in example f, a character reports on another character's (hyena's) speech. Logophoric pronouns are used for both characters, so they are distinguished from the current speaker, but not from each other.

Long Distance Reflexive Logophors

Chinese

In Chinese, there are two types of long-range third person reflexives, simplex and complex. They are ziji and Pr-ziji (pronoun morpheme and ziji), respectively. The relationship between these reflexives and the antecedents are logophoric. The distance between the reflexives and their antecedents can be many clauses and sentences apart.

Ziji is always used logophorically. (Liu 2012).

k. Hung-chieni xiangxin Su Wen-wan yiding jiayou jiajiang shuo zijii yinyou ta wen ta, zhunbei ji shi fanbo

Hung-chien believe Su-Wen-wan surely exaggerate say self lure her kiss her be prepared with fact counter

'Hung-chieni was sure Su Wen-wan had exaggerated everything; saying hei had lured her and kissed her; and he was prepared to counter

lies with facts.' (Liu 2012:72)

While the logophoric use of Pr-ziji is optional, its primary role is to be an emphatic or intensive expression of pronoun. Emphatic use is shown in example l. In example sentence l that uses a Pr-ziji for emphatic purposes, substituting the Pr-ziji (here, taziji) for ziji can reduce the emphasis and suggest logophoric referencing (Liu 2012).

l. Lao Tong Baoi suiran bu hen jide zufu shi zenyang "zuoren", dan fuqin de qinjian zonghou,tai shi qinyan kanjian

Old Tong Bao although not very recall grandpa be what sort of man but father MM diligence honesty he just with his own eyes see

de; tazijii ye shi guiju ren...

PA himself also be respectable man

'Although Old Tong Baoi couldn't recall what sort of man his grandfather was, hei knew his father had been hardworking and honest --

he had seen that with his own eyes. Old Tong Bao himselfi was a respectable person;...' (Liu 2012:75)

Japanese

Prior to the first usage of the term "logophor", Kuno Susumu (1972) analyzed the licensing of the use of the Japanese reflexive pronoun zibun. His analysis focused on the occurrence of this pronoun in direct discourse in which the internal feeling of someone other than the speaker is being represented. Kuno argues that what permits the usage of zibun is a context in which the individual which the speaker is referring to is aware of the state or event under discussion - i.e., this individual's perspective must be represented.

g. Johni wa, Mary ga zibuni ni ai ni kuru hi wa, sowasowa site-iru yo.

meet to come days excited is

'John is excited on days when Mary comes to see him.'

h. *Johni wa, Mary ga zibuni o miru toki wa, itu mo kaoiro ga warui

self see when always complexion bad

soo da.

I hear

'I hear that John looks pale whenever Mary sees him.' (Kuno 1972:182)

The g. sentence is considered grammatical because the individual being discussed (John) is aware that Mary comes to see him. Conversely, sentence h. is ungrammatical because it is not possible for John to look pale when he is aware that Mary sees him. As such, John's awareness of the event or state being communicated in the embedded sentence determines whether or not the entire sentences is grammatical. Similarly to other logophors, the antecedent of the reflexive zibun need not occur in the same sentence, as is the case for non-logophoric reflexives. This is demonstrated in the example above, in which the antecedent in sentence a. occurs in the matrix sentence, while zibun occurs in the embedded clause. Although traditionally referred to as "indirect reflexives", logophoric pronouns such as zibun are also referred to as long-distance, or free anaphors (Reuland 2006:4).

Although the grammatical usage of zibun is conditioned by semantic factors (namely, the representation of the direct internal feeling or knowledge of an individual other than the speaker), syntactic restrictions also play a role. For example, the usage of zibun in a matrix sentence requires coreference with the subject of the sentence (not the object):

i. John wa Mary o zibun no i.e. de korosita.

self 's house in killed

'John killed Mary in (lit.) self's house.'

j. Mary wa John ni zibun no ie de koros-are-ta.

'Mary was killed by John in (lit.) self's house.' (Kuno 1972:178)

In the above sentences, zibun can only refer to the subjects of the sentences - "John" in sentence i. and "Mary" in sentence j. As such, the passivized sentence j. is not equivalent in meaning to sentence e. Importantly, that coreferent of zibun need not be aware of the action or state represented in the sentence - for instance, it is not implied in sentence j. that Mary was aware that she was killed in her house. This use of zibun appears to be restricted to a non-logophoric context. In line with Clements' characterization of indirect reflexives, the logophoric pronoun is homophonous with the (non-logophoric) reflexive pronoun (Clements 1975, p. 3).

Logophoricity and Binding Theory

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (October 2014) |

Previous Wikipedia Article

In linguistics, logophoricity is a kind of coreferential anaphora, where the third-person subject of a dependent clause is marked as identical to the subject of the main clause. Logophoric systems are frequently restricted to indirect speech.

Logophoric pronouns are common in the languages of West Africa. In Ewe, for example, they are used to show that the subject in reported speech or thought is the same as the person doing the speaking or thinking. In English, such sentences as "he thought that he went" are ambiguous, as it is not clear whether the two instances of "he" are the same person; Ewe, in contrast, has different words for "he", yɛ and e, to distinguish these two meanings:

- Logophoric coreference: Kofi be yɛ-dzo "Kofi said s/he (Kofi) left." (special logophoric pronoun: e-be yɛ-dzo)

- Unmarked switch reference: Kofi be e-dzo "Kofi said s/he (someone else) left." (usual pronoun: e-be e-dzo)

Mabaan, a Luo language of Sudan, has the opposite system, where the usual pronoun indicates coreference, and a special 'anti-logophoric' pronoun indicates switch reference:

- Unmarked coreference: ʔɛ́kɛ̀ ɡɔ́kè ʔáɡē ʔɛ́kɛ̀ kâɲɟɛ́ "He said that he (himself) will.swim" (usual pronoun)

- Anti-logophoric switch reference: ʔɛ́kɛ̀ ɡɔ́kè ʔáɡē ʔɛ̂ktá kâɲɟɛ́ "He said that he (other) will.swim" (special pronoun)

The Chadic language Mupun of Nigeria has one of the most elaborate systems known, with separate object forms and logophoricity for the addressee as well as the speaker:

- wu he, wa she, mo they: subject of main clause, incl. speaker; non-coreferential subject of dependent clause

- wur him, war her: object of main clause, incl. addressee; object of dependent clause non-coreferential to speaker; subject of dependent clause non-coreferetial to addressee

- ɗɪ he, ɗe she, ɗu they: subject of dependent clause coreferential to speaker (logophoric subject)

- ɗin him, ɗe her: object of dependent clause coreferential to speaker (logophoric object)

- gwar he/she: subject of dependent clause, coreferential to addressee (object-subject logophore)

For example (Heine & Nurse 2008:145):

- (sat to say; nə that; ta ɗee to stop by, nas to beat; ji to come)

- Wu sat nə wu ta ɗee n-Jos

- He said that he (other) stopped over in Jos

- Wu sat nə n-nas wur

- He said that I beat him (other)

- N-sat n-wur nə wur ji

- I told him that he (other) should come

- Wu sat nə ta ɗɪ ɗee n-Jos

- He said that he (himself) stopped over in Jos

- Wu sat nə n-nas ɗin

- He said that I beat him (himself)

- N-sat n-wur nə gwar ji

- I told him that he (himself) should come

See also

References

- Hagège, Claude (1974), "Les pronoms logophoriques", Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris, 69: 287–310

- Clements, George N. (1975), "The Logophoric Pronoun in Ewe: Its Role in Discourse", Journal of West African Languages, 2: 141–177

- Cunrow, Timothy J. (2002), "Three Types of Logophoricity in African Languages", Studies in African Linguistics, 31: 1–26

- Hedinger, Robert (1984), "Reported Speech in Akɔɔse", Studies in African Linguistics, 12 (3): 81–102

- Hyman, Larry M. & Bernard Comrie (1981), "Logophoric Reference in Gokana", Studies in African Linguistics, 3 (1): 19–37

- Kuno, Susumu (1972), "Pronominalization, Reflexivization, and Direct Discourse", Linguistic Inquiry, 3: 161–195

- Liu, Lijin (2012), "Logophoricity, Highlighting and Contrasting: A Pragmatic Study of Third-person Reflexives in Chinese Discourse", English Language and Literature Studies, 2: 69–84

- Nikitina, Tatiana (2012), "Logophoric Discourse and First Person Reporting in Wan (West Africa)", Anthropological Linguistics, 54: 280–301

- Reuland, E. (2006), "Chapter 38. Logophoricity", The Blackwell Companion to Syntax, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 1–20, ISBN 9781405114851, retrieved 2014-10-28

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)