Western painting

| History of art |

|---|

The history of Western painting represents a continuous, though disrupted, tradition from antiquity until the present time.[2] Until the mid-19th century it was primarily concerned with representational and Classical modes of production, after which time more modern, abstract and conceptual forms gained favor.[3]

Developments in Western painting historically parallel those in Eastern painting, in general a few centuries later.[4] African art, Islamic art, Indian art,[5] Chinese art, and Japanese art[6] each had a significant influence on Western art, and, eventually, vice-versa.[7]

Initially serving imperial, private, civic, and religious patronage, Western painting later found audiences in the aristocracy and the middle class. From the Middle Ages through the Renaissance painters worked for the church and a wealthy aristocracy.[8] Beginning with the Baroque era artists received private commissions from a more educated and prosperous middle class.[9] The idea of "art for art's sake"[10] began to find expression in the work of the Romantic painters like Francisco de Goya, John Constable, and J. M. W. Turner.[11] During the 19th century commercial galleries became established and continued to provide patronage in the 20th century.[12][13][14]

Western painting reached its zenith in Europe during the Renaissance, in conjunction with the refinement of drawing, use of perspective, ambitious architecture, tapestry, stained glass, sculpture, and the period before and after the advent of the printing press.[15] Following the depth of discovery and the complexity of innovations of the Renaissance, the rich heritage of Western painting (from the Baroque to Contemporary art). The history of painting continues into the 21st century.[16]

Pre-history

-

Lascaux, horse

-

Lascaux, Bulls and Horses

-

Bison, in the great hall of policromes, Cave of Altamira, Spain

-

Petroglyphs, from Sweden, Nordic Bronze Age (painted)

-

Pictographs from the Great Gallery, Canyonlands National Park, Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, c. 1500 BCE

-

Cueva de las Manos (Spanish for Cave of the Hands) in the Santa Cruz province in Argentina, c. 550 BC

The history of painting reaches back in time to artifacts from pre-historic humans, and spans all cultures. The oldest known paintings are at the Grotte Chauvet in France, claimed by some historians to be about 32,000 years old. They are engraved and painted using red ochre and black pigment and show horses, rhinoceros, lions, buffalo, mammoth, or humans often hunting. There are examples of cave paintings all over the world—in France, India, Spain, Portugal, China, Australia etc. There are many common themes throughout the many different places that the paintings have been found; implying the universality of purpose and similarity of the impulses that might have created the imagery. Various conjectures have been made as to the meaning these paintings had to the people who made them. Prehistoric men may have painted animals to "catch" their soul or spirit in order to hunt them more easily, or the paintings may represent an animistic vision and homage to surrounding nature, or they may be the result of a basic need of expression that is innate to human beings, or they may be recordings of the life experiences of the artists and related stories from the members of their circle.

Western painting

Egypt, Greece and Rome

Also see Ancient art

-

Sennedjem plows his fields with a pair of oxen, c. 1200 BC

-

Ancient Egypt, The Goddess Isis, wall painting, c. 1360 BC

-

Ancient Egypt, Queen Nefertari

-

Pitsa panels, one of the few surviving panel paintings from Archaic Greece, c. 540–530 BC

Ancient Egypt, a civilization with strong traditions of architecture and sculpture (both originally painted in bright colours), had many mural paintings in temples and buildings, and painted illustrations on papyrus manuscripts. Egyptian wall painting and decorative painting is often graphic, sometimes more symbolic than realistic. Egyptian painting depicts figures in bold outline and flat silhouette, in which symmetry is a constant characteristic. Egyptian painting has close connection with its written language—called Egyptian hieroglyphs. Painted symbols are found amongst the first forms of written language. The Egyptians also painted on linen, remnants of which survive today. Ancient Egyptian paintings survived due to the extremely dry climate. The ancient Egyptians created paintings to make the afterlife of the deceased a pleasant place. The themes included journey through the afterworld or their protective deities introducing the deceased to the gods of the underworld. Some examples of such paintings are paintings of the gods and goddesses Ra, Horus, Anubis, Nut, Osiris and Isis. Some tomb paintings show activities that the deceased were involved in when they were alive and wished to carry on doing for eternity. In the New Kingdom and later, the Book of the Dead was buried with the entombed person. It was considered important for an introduction to the afterlife.

To the north of Egypt was the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete. The wall paintings found in the palace of Knossos are similar to those of the Egyptians but much more free in style.

Around 1100 BC, tribes from the north of Greece conquered Greece and its art took a new direction. The culture of Ancient Greece is noteworthy for its outstanding contributions to the visual arts. Painting on pottery of Ancient Greece and ceramics gives a particularly informative glimpse into the way society in Ancient Greece functioned. Many fine examples of Black-figure vase painting and Red-figure vase painting still exist. Some famous Greek painters who worked on wood panels and are mentioned in texts are Apelles, Zeuxis and Parrhasius; however, with the single exception of the Pitsa panels, no examples of Ancient Greek panel painting survive, only written descriptions by their contemporaries or later Romans. Zeuxis lived in the 5th century BC and was said to be the first to use sfumato. According to Pliny the Elder, the realism of his paintings was such that birds tried to eat the painted grapes. Apelles is described as the greatest painter of antiquity, and is noted for perfect technique in drawing, brilliant color, and modeling.

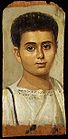

Roman art was influenced by Greece and can in part be taken as descendant from Ancient Greek painting. However, Roman painting does have important unique characteristics. Almost all surviving Roman works are wall paintings, many from villas in Campania, in Southern Italy. Such painting can be grouped into four main "styles" or periods[17] and may contain the first examples of trompe-l'oeil, pseudo-perspective, and pure landscape.[18] Almost the only painted portraits surviving from the Ancient world are a large number of Mummy Portraits of bust form found in the Late Antique cemetery of Al-Fayum. Although these were neither of the best period nor the highest quality,[citation needed] they are impressive in themselves, and suggest the quality of the finest ancient work. A very small number of miniatures from Late Antique illustrated books also survive, as well as a rather larger number of copies of them from the Early Medieval period.

Middle Ages

-

Byzantine icon, 6th century

-

Byzantine art mosaics in Ravenna

-

Byzantine, 6th century

-

The Capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade, c. 1099

-

The Morgan Leaf, from the Winchester Bible 1160–75, Scenes from the life of David

-

Yaroslavl Gospels c. 1220s

-

Carolingian Saint Mark

-

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, St Francis of Assisi, 1235

The rise of Christianity imparted a different spirit and aim to painting styles. Byzantine art, once its style was established by the 6th century, placed great emphasis on retaining traditional iconography and style, and gradually evolved during the thousand years of the Byzantine Empire and the living traditions of Greek and Russian Orthodox icon-painting. Byzantine painting has a hieratic feeling and icons were and still are seen as a representation of divine revelation. There were many frescos, but fewer of these have survived than mosaics. Byzantine art has been compared to contemporary abstraction, in its flatness and highly stylised depictions of figures and landscape. Some periods of Byzantine art, especially the so-called Macedonian art of around the 10th century, are more flexible in approach. Frescos of the Palaeologian Renaissance of the early 14th century survive in the Chora Church in Istanbul.

In post-Antique Catholic Europe the first distinctive artistic style to emerge that included painting was the Insular art of the British Isles, where the only surviving examples are miniatures in Illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells.[19] These are most famous for their abstract decoration, although figures, and sometimes scenes, were also depicted, especially in Evangelist portraits. Carolingian and Ottonian art also survives mostly in manuscripts, although some wall-painting remain, and more are documented. The art of this period combines Insular and "barbarian" influences with a strong Byzantine influence and an aspiration to recover classical monumentality and poise.

Walls of Romanesque and Gothic churches were decorated with frescoes as well as sculpture and many of the few remaining murals have great intensity, and combine the decorative energy of Insular art with a new monumentality in the treatment of figures. Far more miniatures in Illuminated manuscripts survive from the period, showing the same characteristics, which continue into the Gothic period.

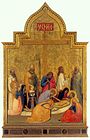

Panel painting becomes more common during the Romanesque period, under the heavy influence of Byzantine icons. Towards the middle of the 13th century, Medieval art and Gothic painting became more realistic, with the beginnings of interest in the depiction of volume and perspective in Italy with Cimabue and then his pupil Giotto. From Giotto on, the treatment of composition by the best painters also became much more free and innovative. They are considered to be the two great medieval masters of painting in western culture. Cimabue, within the Byzantine tradition, used a more realistic and dramatic approach to his art. His pupil, Giotto, took these innovations to a higher level which in turn set the foundations for the western painting tradition. Both artists were pioneers in the move towards naturalism.

Churches were built with more and more windows and the use of colorful stained glass become a staple in decoration. One of the most famous examples of this is found in the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. By the 14th century Western societies were both richer and more cultivated and painters found new patrons in the nobility and even the bourgeoisie. Illuminated manuscripts took on a new character and slim, fashionably dressed court women were shown in their landscapes. This style soon became known as International style and tempera panel paintings and altarpieces gained importance.

Renaissance and Mannerism

-

Masaccio The Expulsion Of Adam and Eve from Eden, before and after restoration

The Renaissance (French for 'rebirth'), a cultural movement roughly spanning the 14th through the mid-17th century, heralded the study of classical sources, as well as advances in science which profoundly influenced European intellectual and artistic life. In Italy artists like Paolo Uccello, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Andrea Mantegna, Filippo Lippi, Giorgione, Tintoretto, Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raphael, Giovanni Bellini and Titian took painting to a higher level through the use of perspective, the study of human anatomy and proportion, and through their development of an unprecedented refinement in drawing and painting techniques.

Flemish, Dutch and German painters of the Renaissance such as Hans Holbein the Younger, Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach, Matthias Grünewald, Hieronymous Bosch, and Pieter Bruegel represent a different approach from their Italian colleagues, one that is more realistic and less idealized. Genre painting became a popular idiom amongst the Northern painters like Pieter Bruegel. The adoption of oil painting whose invention was traditionally, but erroneously, credited to Jan van Eyck, (an important transitional figure who bridges painting in the Middle Ages with painting of the early Renaissance), made possible a new verisimilitude in depicting reality. Unlike the Italians, whose work drew heavily from the art of Ancient Greece and Rome, the northerners retained a stylistic residue of the sculpture and illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages.

Renaissance painting reflects the revolution of ideas and science (astronomy, geography) that occurred in this period, the Reformation, and the invention of the printing press. Dürer, considered one of the greatest of printmakers, states that painters are not mere artisans but thinkers as well. With the development of easel painting in the Renaissance, painting gained independence from architecture. Following centuries dominated by religious imagery, secular subject matter slowly returned to Western painting. Artists included visions of the world around them, or the products of their own imaginations in their paintings. Those who could afford the expense could become patrons and commission portraits of themselves or their family.

In the 16th century, movable pictures which could be hung easily on walls, rather than paintings affixed to permanent structures, came into popular demand.[20]

The High Renaissance gave rise to a stylized art known as Mannerism. In place of the balanced compositions and rational approach to perspective that characterized art at the dawn of the 16th century, the Mannerists sought instability, artifice, and doubt. The unperturbed faces and gestures of Piero della Francesca and the calm Virgins of Raphael are replaced by the troubled expressions of Pontormo and the emotional intensity of El Greco.

Baroque and Rococo

Baroque painting is associated with the Baroque cultural movement, a movement often identified with Absolutism and the Counter Reformation or Catholic Revival;[21][22] the existence of important Baroque painting in non-absolutist and Protestant states also, however, underscores its popularity, as the style spread throughout Western Europe.[23]

Baroque painting is characterized by great drama, rich, deep color, and intense light and dark shadows. Baroque art was meant to evoke emotion and passion instead of the calm rationality that had been prized during the Renaissance. During the period beginning around 1600 and continuing throughout the 17th century, painting is characterized as Baroque. Among the greatest painters of the Baroque are Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Frans Hals, Rubens, Velázquez, Poussin, and Jan Vermeer. Caravaggio is an heir of the humanist painting of the High Renaissance. His realistic approach to the human figure, painted directly from life and dramatically spotlit against a dark background, shocked his contemporaries and opened a new chapter in the history of painting. Baroque painting often dramatizes scenes using light effects; this can be seen in works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Le Nain and La Tour.

During the 18th century, Rococo followed as a lighter extension of Baroque, often frivolous and erotic. Rococo developed first in the decorative arts and interior design in France. Louis XV's succession brought a change in the court artists and general artistic fashion. The 1730s represented the height of Rococo development in France exemplified by the works of Antoine Watteau and François Boucher. Rococo still maintained the Baroque taste for complex forms and intricate patterns, but by this point, it had begun to integrate a variety of diverse characteristics, including a taste for Oriental designs and asymmetric compositions.

The Rococo style spread with French artists and engraved publications. It was readily received in the Catholic parts of Germany, Bohemia, and Austria, where it was merged with the lively German Baroque traditions. German Rococo was applied with enthusiasm to churches and palaces, particularly in the south, while Frederician Rococo developed in the Kingdom of Prussia.

The French masters Watteau, Boucher and Fragonard represent the style, as do Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin who was considered by some as the best French painter of the 18th century – the Anti-Rococo. Portraiture was an important component of painting in all countries, but especially in England, where the leaders were William Hogarth, in a blunt realist style, and Francis Hayman, Angelica Kauffman (who was Swiss), Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds in more flattering styles influenced by Anthony van Dyck. While in France during the Rococo era Jean-Baptiste Greuze (the favorite painter of Denis Diderot),[24] Maurice Quentin de La Tour, and Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun were highly accomplished Portrait painters and History painters.

William Hogarth helped develop a theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty. Though not intentionally referencing the movement, he argued in his Analysis of Beauty (1753) that the undulating lines and S-curves prominent in Rococo were the basis for grace and beauty in art or nature (unlike the straight line or the circle in Classicism). The beginning of the end for Rococo came in the early 1760s as figures like Voltaire and Jacques-François Blondel began to voice their criticism of the superficiality and degeneracy of the art. Blondel decried the "ridiculous jumble of shells, dragons, reeds, palm-trees and plants" in contemporary interiors.[25]

By 1785, Rococo had passed out of fashion in France, replaced by the order and seriousness of Neoclassical artists like Jacques-Louis David.

19th century: Neo-classicism, History painting, Romanticism, Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Symbolism

also see main articles Neoclassicism, History painting, Romanticism, Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Symbolism

-

Jacques-Louis David 1787

-

John Singleton Copley, 1778

-

Antoine-Jean Gros, 1804

-

John Constable 1802

-

Francisco Goya 1814

-

Théodore Géricault 1819

-

Caspar David Friedrich c. 1822

-

Karl Brullov 1827

-

Eugène Delacroix, 1830

-

J. M. W. Turner 1838

-

Ivan Aivazovsky 1850

-

Gustave Courbet 1849–1850

-

Jan Matejko 1862

-

Albert Bierstadt, 1866

-

Camille Corot c. 1867

-

Claude Monet 1872

-

Edgar Degas 1876

-

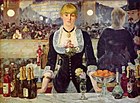

Édouard Manet 1882

-

Aleksander Gierymski 1884

-

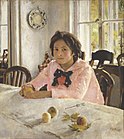

Valentin Serov 1887

-

Vincent van Gogh 1888

-

Ilya Repin 1891

-

Józef Chełmoński 1896

-

Paul Gauguin 1897–1898

-

Georges-Pierre Seurat 1884–1886

-

Thomas Eakins, 1884–1885

-

Albert Pinkham Ryder, 1890

-

Winslow Homer 1899

-

Witold Wojtkiewicz 1905

-

Paul Cézanne 1906

After Rococo there arose in the late 18th century, in architecture, and then in painting severe neo-classicism, best represented by such artists as David and his heir Ingres. Ingres' work already contains much of the sensuality, but none of the spontaneity, that was to characterize Romanticism. This movement turned its attention toward landscape and nature as well as the human figure and the supremacy of natural order above mankind's will. There is a pantheist philosophy (see Spinoza and Hegel) within this conception that opposes Enlightenment ideals by seeing mankind's destiny in a more tragic or pessimistic light. The idea that human beings are not above the forces of Nature is in contradiction to Ancient Greek and Renaissance ideals where mankind was above all things and owned his fate. This thinking led romantic artists to depict the sublime, ruined churches, shipwrecks, massacres and madness.

By the mid-19th century painters became liberated from the demands of their patronage to only depict scenes from religion, mythology, portraiture or history. The idea "art for art's sake" began to find expression in the work of painters like Francisco de Goya, John Constable, and J.M.W. Turner. Romantic painters turned landscape painting into a major genre, considered until then as a minor genre or as a decorative background for figure compositions. Some of the major painters of this period are Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Géricault, J. M. W. Turner, Caspar David Friedrich and John Constable. Francisco Goya's late work demonstrates the Romantic interest in the irrational, while the work of Arnold Böcklin evokes mystery and the paintings of Aesthetic movement artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler evoke both sophistication and decadence. In the United States the Romantic tradition of landscape painting was known as the Hudson River School:[26] exponents include Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, and John Frederick Kensett. Luminism was a movement in American landscape painting related to the Hudson River School.

The leading Barbizon School painter Camille Corot painted in both a romantic and a realistic vein; his work prefigures Impressionism, as does the paintings of Eugène Boudin who was one of the first French landscape painters to paint outdoors. Boudin was also an important influence on the young Claude Monet, whom in 1857 he introduced to Plein air painting. A major force in the turn towards Realism at mid-century was Gustave Courbet. In the latter third of the century Impressionists like Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, and Edgar Degas worked in a more direct approach than had previously been exhibited publicly. They eschewed allegory and narrative in favor of individualized responses to the modern world, sometimes painted with little or no preparatory study, relying on deftness of drawing and a highly chromatic palette. Manet, Degas, Renoir, Morisot, and Cassatt concentrated primarily on the human subject. Both Manet and Degas reinterpreted classical figurative canons within contemporary situations; in Manet's case the re-imaginings met with hostile public reception. Renoir, Morisot, and Cassatt turned to domestic life for inspiration, with Renoir focusing on the female nude. Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley used the landscape as their primary motif, the transience of light and weather playing a major role in their work. While Sisley most closely adhered to the original principals of the Impressionist perception of the landscape, Monet sought challenges in increasingly chromatic and changeable conditions, culminating in his series of monumental works of Water Lilies painted in Giverny.

Pissarro adopted some of the experiments of Post-Impressionism. Slightly younger Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Georges-Pierre Seurat, along with Paul Cézanne led art to the edge of modernism; for Gauguin Impressionism gave way to a personal symbolism; Seurat transformed Impressionism's broken color into a scientific optical study, structured on frieze-like compositions; Van Gogh's turbulent method of paint application, coupled with a sonorous use of color, predicted Expressionism and Fauvism, and Cézanne, desiring to unite classical composition with a revolutionary abstraction of natural forms, would come to be seen as a precursor of 20th-century art. The spell of Impressionism was felt throughout the world, including in the United States, where it became integral to the painting of American Impressionists such as Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and Theodore Robinson. It also exerted influence on painters who were not primarily Impressionistic in theory, like the portrait and landscape painter John Singer Sargent. At the same time in America at the turn of the 20th century there existed a native and nearly insular realism, as richly embodied in the figurative work of Thomas Eakins, the Ashcan School, and the landscapes and seascapes of Winslow Homer, all of whose paintings were deeply invested in the solidity of natural forms. The visionary landscape, a motive largely dependent on the ambiguity of the nocturne, found its advocates in Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Albert Blakelock.

In the late 19th century there also were several, rather dissimilar, groups of Symbolist painters whose works resonated with younger artists of the 20th century, especially with the Fauvists and the Surrealists. Among them were Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Henri Fantin-Latour, Arnold Böcklin, Edvard Munch, Félicien Rops, and Jan Toorop, and Gustav Klimt amongst others including the Russian Symbolists like Mikhail Vrubel.

Symbolist painters mined mythology and dream imagery for a visual language of the soul, seeking evocative paintings that brought to mind a static world of silence. The symbols used in Symbolism are not the familiar emblems of mainstream iconography but intensely personal, private, obscure and ambiguous references. More a philosophy than an actual style of art, the Symbolist painters influenced the contemporary Art Nouveau movement and Les Nabis. In their exploration of dreamlike subjects, symbolist painters are found across centuries and cultures, as they are still today; Bernard Delvaille has described René Magritte's surrealism as "Symbolism plus Freud".[27]

20th century

-

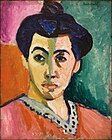

Henri Matisse, 1905, Fauvism

-

Henri Matisse, 1909, late Fauvism

-

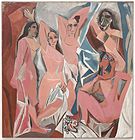

Pablo Picasso, 1907, early Cubism

-

Georges Braque, 1910, Analytic Cubism

The heritage of painters like Van Gogh, Cézanne, Gauguin, and Seurat was essential for the development of modern art. At the beginning of the 20th century Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubist Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de Vlaminck revolutionized the Paris art world with "wild", multi-colored, expressive, landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism (as seen in the gallery above). Henri Matisse's second version of The Dance signifies a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting.[28] It reflects Matisse's incipient fascination with primitive art: the intense warm colors against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism. Pablo Picasso made his first cubist paintings based on Cézanne's idea that all depiction of nature can be reduced to three solids: cube, sphere and cone. With the painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon 1907, (see gallery) Picasso dramatically created a new and radical picture depicting a raw and primitive brothel scene with five prostitutes, violently painted women, reminiscent of African tribal masks and his own new Cubist inventions. Cubism (see gallery) was jointly developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, exemplified by Violin and Candlestick, Paris, (seen above) from about 1908 through 1912. The first clear manifestation of Cubism was practised by Braque, Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Henri Le Fauconnier, and Robert Delaunay. Juan Gris, Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky and others soon joined.[29] Synthetic cubism, practiced by Braque and Picasso, is characterized by the introduction of different textures, surfaces, collage elements, papier collé and a large variety of merged subject matter.[29]

The Salon d'Automne of 1905 brought notoriety and attention to the works of Henri Matisse and Fauvism. The group gained their name, after critic Louis Vauxcelles described their work with the phrase "Donatello chezes fauves" ("Donatello among the wild beasts"),[30] contrasting the paintings with a Renaissance-type sculpture that shared the room with them.[31] Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), an artist that Picasso knew and admired and who was not a Fauve, had his large jungle scene "The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope" also hanging near the works by Matisse and which may have had an influence on the particular sarcastic term used in the press.[32] Vauxcelles' comment was printed on 17 October 1905 in the daily newspaper Gil Blas, and passed into popular usage.[31][33]

Although the pictures were widely derided—"A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public", declared the critic Camille Mauclair (1872–1945)—they also attracted some favorable attention.[31] The painting that was singled out for the most attacks was Matisse's Woman with a Hat; the purchase of this work by Gertrude and Leo Stein had a very positive effect on Matisse, who was suffering demoralization from the bad reception of his work.[31]

During the years between 1910 and the end of World War I and after the heyday of cubism, several movements emerged in Paris. Giorgio de Chirico moved to Paris in July 1911, where he joined his brother Andrea (the poet and painter known as Alberto Savinio). Through his brother he met Pierre Laprade a member of the jury at the Salon d'Automne, where he exhibited three of his dreamlike works: Enigma of the Oracle, Enigma of an Afternoon and Self-Portrait. During 1913 he exhibited his work at the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, his work was noticed by Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire and several others. His compelling and mysterious paintings are considered instrumental to the early beginnings of Surrealism. Song of Love 1914, is one of the most famous works by de Chirico and is an early example of the surrealist style, though it was painted ten years before the movement was "founded" by André Breton in 1924 (see gallery).

In the first two decades of the 20th century and after cubism, several other important movements emerged; Futurism (Balla), Abstract art (Kandinsky) Der Blaue Reiter (Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc), Bauhaus (Kandinsky and Klee), Orphism, (Delaunay and Kupka), Synchromism (Russell), De Stijl (van Doesburg and Mondrian), Suprematism (Malevich), Constructivism (Tatlin), Dadaism (Duchamp, Picabia and Arp), and Surrealism (de Chirico, André Breton, Miró, Magritte, Dalí and Ernst). Modern painting influenced all the visual arts, from Modernist architecture and design, to avant-garde film, theatre and modern dance and became an experimental laboratory for the expression of visual experience, from photography and concrete poetry to advertising art and fashion. Van Gogh's painting exerted great influence upon 20th-century Expressionism, as can be seen in the work of the Fauves, Die Brücke (a group led by German painter Ernst Kirchner), and the Expressionism of Edvard Munch, Egon Schiele, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine and others.

Pioneers of abstraction

-

Piet Mondrian, 1911, early De Stijl

-

Wassily Kandinsky, 1913, birth of Abstract Art

-

Robert Delaunay, 1912–1913, Orphism

-

Morgan Russell, 1913–14 Synchromism

-

Giacomo Balla, 1913–1914, Futurism

-

Kazimir Malevich, 1916, Suprematism

Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian painter, printmaker and art theorist, one of the most famous 20th-century artists is generally considered the first important painter of modern abstract art. As an early modernist, in search of new modes of visual expression, and spiritual expression, he theorized as did contemporary occultists and theosophists, that pure visual abstraction had corollary vibrations with sound and music. They posited that pure abstraction could express pure spirituality. His earliest abstractions were generally titled as the example in the (above gallery) Composition VII, making connection to the work of the composers of music. Kandinsky included many of his theories about abstract art in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Piet Mondrian's art was also related to his spiritual and philosophical studies. In 1908 he became interested in the theosophical movement launched by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in the late 19th century. Blavatsky believed that it was possible to attain a knowledge of nature more profound than that provided by empirical means, and much of Mondrian's work for the rest of his life was inspired by his search for that spiritual knowledge. Other major pioneers of early abstraction include Swedish painter Hilma af Klint, Russian painter Kazimir Malevich, and Swiss painter Paul Klee. Robert Delaunay was a French artist who is associated with Orphism, (reminiscent of a link between pure abstraction and cubism). His later works were more abstract, reminiscent of Paul Klee. His key contributions to abstract painting refer to his bold use of color, and a clear love of experimentation of both depth and tone. At the invitation of Wassily Kandinsky, Delaunay and his wife the artist Sonia Delaunay, joined The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), a Munich-based group of abstract artists, in 1911, and his art took a turn to the abstract. Still other important pioneers of abstract painting include Czech painter, František Kupka and Synchromism, an art movement founded in 1912 by American artists Stanton MacDonald-Wright and Morgan Russell that closely resembles Orphism.

Fauvism, Der Blaue Reiter, Die Brücke

-

Henri Matisse, Fauvism, 1905

-

André Derain, Fauvism, 1906

-

Maurice de Vlaminck, Fauvism, 1906

-

Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter, 1913–14

-

Ernst Kirchner, Die Brücke, 1913

-

Otto Mueller, Die Brücke, 1919

Les Fauves (French for The Wild Beasts) were early-20th-century painters, experimenting with freedom of expression through color. The name was given, humorously and not as a compliment, to the group by art critic Louis Vauxcelles. Fauvism was a short-lived and loose grouping of early 20th-century artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities, and the imaginative use of deep color over the representational values. Fauvists made the subject of the painting easy to read, exaggerated perspectives and an interesting prescient prediction of the Fauves was expressed in 1888 by Paul Gauguin to Paul Sérusier,

"How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion."

The leaders of the movement were Henri Matisse and André Derain – friendly rivals of a sort, each with his own followers. Ultimately Matisse became the yang to Picasso's yin in the 20th century. Fauvist painters included Albert Marquet, Charles Camoin, Maurice de Vlaminck, Raoul Dufy, Othon Friesz, the Dutch painter Kees van Dongen, and Picasso's partner in Cubism, Georges Braque amongst others.[34]

Fauvism, as a movement, had no concrete theories, and was short lived, beginning in 1905 and ending in 1907, they only had three exhibitions. Matisse was seen as the leader of the movement, due to his seniority in age and prior self-establishment in the academic art world. His 1905 portrait of Mme. Matisse The Green Line, (above), caused a sensation in Paris when it was first exhibited. He said he wanted to create art to delight; art as a decoration was his purpose and it can be said that his use of bright colors tries to maintain serenity of composition. In 1906 at the suggestion of his dealer Ambroise Vollard, André Derain went to London and produced a series of paintings like Charing Cross Bridge, London (above) in the Fauvist style, paraphrasing the famous series by the Impressionist painter Claude Monet.

By 1907 Fauvism no longer was a shocking new movement, soon it was replaced by Cubism on the critics radar screen as the latest new development in Contemporary Art of the time. In 1907 Appolinaire, commenting about Matisse in an article published in La Falange, said, "We are not here in the presence of an extravagant or an extremist undertaking: Matisse's art is eminently reasonable."[35]

Der Blaue Reiter was a German movement lasting from 1911 to 1914, fundamental to Expressionism, along with Die Brücke, a group of German expressionist artists formed in Dresden in 1905. Founding members of Die Brücke were Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Later members included Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and others. This was a seminal group, which in due course had a major impact on the evolution of modern art in the 20th century and created the style of Expressionism.[36]

Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, Alexej von Jawlensky, whose psychically expressive painting of the Russian dancer Portrait of Alexander Sakharoff, 1909, is in the gallery above, Marianne von Werefkin, Lyonel Feininger and others founded the Der Blaue Reiter group in response to the rejection of Kandinsky's painting Last Judgement from an exhibition. Der Blaue Reiter lacked a central artistic manifesto, but was centered around Kandinsky and Marc. Artists Gabriele Münter and Paul Klee were also involved.

The name of the movement comes from a painting by Kandinsky created in 1903 (see illustration). It is also claimed that the name could have derived from Marc's enthusiasm for horses and Kandinsky's love of the colour blue. For Kandinsky, blue is the colour of spirituality: the darker the blue, the more it awakens human desire for the eternal.[37]

Expressionism, Symbolism, American Modernism, Bauhaus

-

Gustav Klimt, Expressionism, 1907–1908

-

Arthur Dove, early American modernism, 1911

-

Stuart Davis, American modernism, 1921

Expressionism and Symbolism are broad rubrics that involve several important and related movements in 20th-century painting that dominated much of the avant-garde art being made in Western, Eastern and Northern Europe. Expressionist works were painted largely between World War I and World War II, mostly in France, Germany, Norway, Russia, Belgium, and Austria. Expressionist artists are related to both Surrealism and Symbolism and are each uniquely and somewhat eccentrically personal. Fauvism, Die Brücke, and Der Blaue Reiter are three of the best known groups of Expressionist and Symbolist painters. Artists as interesting and diverse as Marc Chagall, whose painting I and the Village, (above) tells an autobiographical story that examines the relationship between the artist and his origins, with a lexicon of artistic Symbolism. Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Chaim Soutine, James Ensor, Oskar Kokoschka, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, Franz Marc, Käthe Schmidt Kollwitz, Georges Rouault, Amedeo Modigliani and some of the Americans abroad like Marsden Hartley, and Stuart Davis, were considered influential expressionist painters. Although Alberto Giacometti is primarily thought of as an intense Surrealist sculptor, he made intense expressionist paintings as well.

In the USA during the period between World War I and World War II painters tended to go to Europe for recognition. Modernist artists like Marsden Hartley, Patrick Henry Bruce, Gerald Murphy and Stuart Davis, created reputations abroad. While Patrick Henry Bruce,[38] created cubist related paintings in Europe, both Stuart Davis and Gerald Murphy made paintings that were early inspirations for American pop art[39][40][41] and Marsden Hartley experimented with expressionism. During the 1920s photographer Alfred Stieglitz exhibited Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Alfred Henry Maurer, Charles Demuth, John Marin and other artists including European Masters Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Henri Rousseau, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso, at his New York City gallery the 291.[42] In Europe masters like Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard continued developing their narrative styles independent of any movement.

Dada and Surrealism

-

Francis Picabia, 1916, Dada

-

André Masson, 1922, early Surrealism

-

Hannah Höch, collage, 1919, Dada

-

Max Ernst, 1920, early Surrealism

Marcel Duchamp came to international prominence in the wake of the New York City Armory Show in 1913 where his Nude Descending a Staircase became the cause celebre. He subsequently created the The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, Large Glass. The Large Glass pushed the art of painting to radical new limits being part painting, part collage, part construction. Duchamp (who was soon to renounce artmaking for chess) became closely associated with the Dada movement that began in neutral Zürich, Switzerland, during World War I and peaked from 1916 to 1920. The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature (poetry, art manifestoes, art theory), theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti war politic through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works. Francis Picabia (see above), Man Ray, Kurt Schwitters, Hannah Höch, Tristan Tzara, Hans Richter, Jean Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, along with Duchamp and many others are associated with the Dadaist movement. Duchamp and several Dadaists are also associated with Surrealism, the movement that dominated European painting in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1924 André Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto. The Surrealist movement in painting became synonymous with the avant-garde and which featured artists whose works varied from the abstract to the super-realist. With works on paper like Machine Turn Quickly, (above) Francis Picabia continued his involvement in the Dada movement through 1919 in Zürich and Paris, before breaking away from it after developing an interest in Surrealist art. Yves Tanguy, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí are particularly known for their realistic depictions of dream imagery and fantastic manifestations of the imagination. Joan Miró's The Tilled Field of 1923–1924 verges on abstraction, this early painting of a complex of objects and figures, and arrangements of sexually active characters; was Miró's first Surrealist masterpiece.[43] The more abstract Joan Miró, Jean Arp, André Masson, and Max Ernst were very influential, especially in the United States during the 1940s.

Throughout the 1930s, Surrealism continued to become more visible to the public at large. A Surrealist group developed in Britain and, according to Breton, their 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition was a high-water mark of the period and became the model for international exhibitions. Surrealist groups in Japan, and especially in Latin America, the Caribbean and in Mexico produced innovative and original works.

Dalí and Magritte created some of the most widely recognized images of the movement. The 1928/1929 painting This Is Not A Pipe, by Magritte is the subject of a Michel Foucault 1973 book, This is not a Pipe (English edition, 1991), that discusses the painting and its paradox. Dalí joined the group in 1929, and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935.

Surrealism as a visual movement had found a method: to expose psychological truth by stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, in order to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, and perception, sometimes evoking empathy from the viewer, sometimes laughter and sometimes outrage and bewilderment.

1931 marked a year when several Surrealist painters produced works which marked turning points in their stylistic evolution: in one example (see gallery above) liquid shapes become the trademark of Dalí, particularly in his The Persistence of Memory, which features the image of watches that sag as if they are melting. Evocations of time and its compelling mystery and absurdity.[44]

The characteristics of this style – a combination of the depictive, the abstract, and the psychological – came to stand for the alienation which many people felt in the modernist period, combined with the sense of reaching more deeply into the psyche, to be "made whole with one's individuality."

Max Ernst, whose 1920 painting Murdering Airplane (above), studied philosophy and psychology in Bonn and was interested in the alternative realities experienced by the insane. His paintings may have been inspired by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud's study of the delusions of a paranoiac, Daniel Paul Schreber. Freud identified Schreber's fantasy of becoming a woman as a castration complex. The central image of two pairs of legs refers to Schreber's hermaphroditic desires. Ernst's inscription on the back of the painting reads: The picture is curious because of its symmetry. The two sexes balance one another.[45]

During the 1920s André Masson's work was enormously influential in helping the young artist Joan Miró find his roots in the new Surrealist painting. Miró acknowledged in letters to his dealer Pierre Matisse the importance of Masson as an example to him in his early years in Paris.

Long after personal, political and professional tensions have fragmented the Surrealist group into thin air and ether, Magritte, Miró, Dalí and the other Surrealists continue to define a visual program in the arts. Other prominent surrealist artists include Giorgio de Chirico, Méret Oppenheim, Toyen, Grégoire Michonze, Roberto Matta, Kay Sage, Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, and Leonor Fini among others.

Neue Sachlichkeit, Social realism, regionalism, American Scene painting, Symbolism

-

George Grosz, 1920, Neue Sachlichkeit

-

Thomas Hart Benton, 1920, Regionalism

During the 1920s and the 1930s and the Great Depression, the European art scene was characterized by Surrealism, late Cubism, the Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dada, Neue Sachlichkeit, and Expressionism; and was occupied by masterful modernist color painters like Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard.

In Germany Neue Sachlichkeit ("New Objectivity") emerged as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz and others politicized their paintings. The work of these artists grew out of expressionism, and was a response to the political tensions of the Weimar Republic, and was often sharply satirical.

American Scene painting and the Social Realism and Regionalism movements that contained both political and social commentary dominated the art world in the USA. Artists like Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, George Tooker, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh, and others became prominent. In Latin America besides the Uruguayan painter Joaquín Torres García and Rufino Tamayo from Mexico, the muralist movement with Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, José Orozco, Pedro Nel Gómez and Santiago Martinez Delgado and the Symbolist paintings by Frida Kahlo began a renaissance of the arts for the region, with a use of color and historic, and political messages. Frida Kahlo's Symbolist works also relate strongly to Surrealism and to the Magic Realism movement in literature. The psychological drama in many of Kahlo's self-portraits (above) underscore the vitality and relevance of her paintings to artists in the 21st century.

Diego Rivera is perhaps best known by the public world for his 1933 mural, "Man at the Crossroads", in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. When his patron Nelson Rockefeller discovered that the mural included a portrait of Lenin and other communist imagery, he fired Rivera, and the unfinished work was eventually destroyed by Rockefeller's staff. The film Cradle Will Rock includes a dramatization of the controversy. Frida Kahlo (Rivera's wife's) works are often characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Of her 143 paintings 55 are self-portraits, which frequently incorporate symbolic portrayals of her physical and psychological wounds. Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her paintings' bright colors and dramatic symbolism. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work as well; she combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition—which were often bloody and violent—with surrealist renderings. While her paintings are not overtly Christian—she was, after all, an avowed communist—they certainly contain elements of the macabre Mexican Christian style of religious paintings.

Political activism was an important piece of David Siqueiros' life, and frequently inspired him to set aside his artistic career. His art was deeply rooted in the Mexican Revolution, a violent and chaotic period in Mexican history in which various social and political factions fought for recognition and power. The period from the 1920s to the 1950s is known as the Mexican Renaissance, and Siqueiros was active in the attempt to create an art that was at once Mexican and universal. He briefly gave up painting to focus on organizing miners in Jalisco. He ran a political art workshop in New York City in preparation for the 1936 General Strike for Peace and May Day parade. The young Jackson Pollock attended the workshop and helped build floats for the parade. Between 1937 and 1938 he fought in the Spanish Civil War alongside the Spanish Republican forces, in opposition to Francisco Franco's military coup. He was exiled twice from Mexico, once in 1932 and again in 1940, following his assassination attempt on Leon Trotsky.

During the 1930s radical leftist politics characterized many of the artists connected to Surrealism, including Pablo Picasso.[46] On 26 April 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the Basque town of Gernika was the scene of the "Bombing of Gernika" by the Condor Legion of Nazi Germany's Luftwaffe. The Germans were attacking to support the efforts of Francisco Franco to overthrow the Basque Government and the Spanish Republican government. The town was devastated, though the Biscayan assembly and the Oak of Gernika survived. Pablo Picasso painted his mural sized Guernica to commemorate the horrors of the bombing.[47]

In its final form, Guernica is an immense black and white, 3.5 metre (11 ft) tall and 7.8 metre (23 ft) wide mural painted in oil. The mural presents a scene of death, violence, brutality, suffering, and helplessness without portraying their immediate causes. The choice to paint in black and white contrasts with the intensity of the scene depicted and invokes the immediacy of a newspaper photograph.[48] Picasso painted the mural sized painting called Guernica in protest of the bombing. The painting was first exhibited in Paris in 1937, then Scandinavia, then London in 1938 and finally in 1939 at Picasso's request the painting was sent to the United States in an extended loan (for safekeeping) at MoMA. The painting went on a tour of museums throughout the USA until its final return to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City where it was exhibited for nearly thirty years. Finally in accord with Pablo Picasso's wish to give the painting to the people of Spain as a gift, it was sent to Spain in 1981.[49]

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, through the years of World War II American art was characterized by Social Realism and American Scene Painting (as seen above) in the work of Grant Wood, Edward Hopper, Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton, and several others. Nighthawks (1942) is a painting by Edward Hopper that portrays people sitting in a downtown diner late at night. It is not only Hopper's most famous painting, but one of the most recognizable in American art. It is currently in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. The scene was inspired by a diner (since demolished) in Greenwich Village, Hopper's home neighborhood in Manhattan. Hopper began painting it immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After this event there was a large feeling of gloominess over the country, a feeling that is portrayed in the painting. The urban street is empty outside the diner, and inside none of the three patrons is apparently looking or talking to the others but instead is lost in their own thoughts. This portrayal of modern urban life as empty or lonely is a common theme throughout Hopper's work.

American Gothic is a painting by Grant Wood from 1930. Portraying a pitchfork-holding farmer and a younger woman in front of a house of Carpenter Gothic style, it is one of the most familiar images in 20th-century American art. Art critics had favorable opinions about the painting, like Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley, they assumed the painting was meant to be a satire of rural small-town life. It was thus seen as part of the trend towards increasingly critical depictions of rural America, along the lines of Sherwood Anderson's 1919 Winesburg, Ohio, Sinclair Lewis' 1920 Main Street, and Carl Van Vechten's The Tattooed Countess in literature.[50] However, with the onset of the Great Depression, the painting came to be seen as a depiction of steadfast American pioneer spirit.

Abstract expressionism

-

Franz Kline, 1954, Action Painting

-

Mark Tobey, 1954, Canticle, Abstract Expressionism, Calligraphy, Northwest School. Mark Tobey's style of "automatic writing" relates to the work of Jackson Pollock

The 1940s in New York City heralded the triumph of American abstract expressionism, a modernist movement that combined lessons learned from Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Surrealism, Joan Miró, Cubism, Fauvism, and early Modernism via great teachers in America like Hans Hofmann and John D. Graham. American artists benefited from the presence of Piet Mondrian, Fernand Léger, Max Ernst and the André Breton group, Pierre Matisse's gallery, and Peggy Guggenheim's gallery The Art of This Century, as well as other factors.

Post-Second World War American painting called Abstract expressionism included artists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Clyfford Still, Franz Kline, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Mark Tobey, James Brooks, Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell, Conrad Marca-Relli, Jack Tworkov, Esteban Vicente, William Baziotes, Richard Pousette-Dart, Ad Reinhardt, Hedda Sterne, Jimmy Ernst, Bradley Walker Tomlin, and Theodoros Stamos, among others. American Abstract expressionism got its name in 1946 from the art critic Robert Coates. It is seen as combining the emotional intensity and self-denial of the German Expressionists with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools such as Futurism, the Bauhaus and Synthetic Cubism. Abstract expressionism, Action painting, and Color Field painting are synonymous with the New York School.

Technically Surrealism was an important predecessor for Abstract expressionism with its emphasis on spontaneous, automatic or subconscious creation. Jackson Pollock's dripping paint onto a canvas laid on the floor is a technique that has its roots in the work of André Masson. Another important early manifestation of what came to be abstract expressionism is the work of American Northwest artist Mark Tobey, especially his "white writing" canvases, which, though generally not large in scale, anticipate the "all over" look of Pollock's drip paintings.

Additionally, Abstract expressionism has an image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic and, some feel, rather nihilistic. In practice, the term is applied to any number of artists working (mostly) in New York who had quite different styles, and even applied to work which is not especially abstract nor expressionist. Pollock's energetic "action paintings", with their "busy" feel, are different both technically and aesthetically, to the violent and grotesque Women series of Willem de Kooning. As seen above in the gallery Woman V is one of a series of six paintings made by de Kooning between 1950 and 1953 that depict a three-quarter-length female figure. He began the first of these paintings, Woman I collection: The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, in June 1950, repeatedly changing and painting out the image until January or February 1952, when the painting was abandoned unfinished. The art historian Meyer Schapiro saw the painting in de Kooning's studio soon afterwards and encouraged the artist to persist. De Kooning's response was to begin three other paintings on the same theme; Woman II collection: The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, Woman III, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Woman IV, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. During the summer of 1952, spent at East Hampton, de Kooning further explored the theme through drawings and pastels. He may have finished work on Woman I by the end of June, or possibly as late as November 1952, and probably the other three women pictures were concluded at much the same time.[51] The Woman series are decidedly figurative paintings. Another important artist is Franz Kline, as demonstrated by his painting High Street, 1950 (see gallery) as with Jackson Pollock and other Abstract Expressionists, was labelled an "action painter because of his seemingly spontaneous and intense style, focusing less, or not at all, on figures or imagery, but on the actual brush strokes and use of canvas.

Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, (see above), Adolph Gottlieb, and the serenely shimmering blocks of color in Mark Rothko's work (which is not what would usually be called expressionist and which Rothko denied was abstract), are classified as abstract expressionists, albeit from what Clement Greenberg termed the Color field direction of abstract expressionism. Both Hans Hofmann (see gallery) and Robert Motherwell (gallery) can be comfortably described as practitioners of action painting and Color field painting.

Abstract Expressionism has many stylistic similarities to the Russian artists of the early 20th century such as Wassily Kandinsky. Although it is true that spontaneity or of the impression of spontaneity characterized many of the abstract expressionists works, most of these paintings involved careful planning, especially since their large size demanded it. An exception might be the drip paintings of Pollock.

Why this style gained mainstream acceptance in the 1950s is a matter of debate. American Social realism had been the mainstream in the 1930s. It had been influenced not only by the Great Depression but also by the Social Realists of Mexico such as David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera. The political climate after World War II did not long tolerate the social protests of those painters. Abstract expressionism arose during World War II and began to be showcased during the early 1940s at galleries in New York like The Art of This Century Gallery. The late 1940s through the mid-1950s ushered in the McCarthy era. It was after World War II and a time of political conservatism and extreme artistic censorship in the United States. Some people have conjectured that since the subject matter was often totally abstract, Abstract expressionism became a safe strategy for artists to pursue this style. Abstract art could be seen as apolitical. Or if the art was political, the message was largely for the insiders. However those theorists are in the minority. As the first truly original school of painting in America, Abstract expressionism demonstrated the vitality and creativity of the country in the post-war years, as well as its ability (or need) to develop an aesthetic sense that was not constrained by the European standards of beauty.

Although Abstract expressionism spread quickly throughout the United States, the major centers of this style were New York City and California, especially in the New York School, and the San Francisco Bay area. Abstract expressionist paintings share certain characteristics, including the use of large canvases, an "all-over" approach, in which the whole canvas is treated with equal importance (as opposed to the center being of more interest than the edges. The canvas as the arena became a credo of Action painting, while the integrity of the picture plane became a credo of the Color Field painters. Many other artists began exhibiting their abstract expressionist related paintings during the 1950s including Alfred Leslie, Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Cy Twombly, Milton Resnick, Michael Goldberg, Norman Bluhm, Ray Parker, Nicolas Carone, Grace Hartigan, Friedel Dzubas, and Robert Goodnough among others.

During the 1950s Color Field painting initially referred to a particular type of abstract expressionism, especially the work of Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb. It essentially involved abstract paintings with large, flat expanses of color that expressed the sensual, and visual feelings and properties of large areas of nuanced surface. Art critic Clement Greenberg perceived Color Field painting as related to but different from Action painting. The overall expanse and gestalt of the work of the early color field painters speaks of an almost religious experience, awestruck in the face of an expanding universe of sensuality, color and surface. During the early-to-mid-1960s Color Field painting came to refer to the styles of artists like Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland, and Helen Frankenthaler, whose works were related to second-generation abstract expressionism, and to younger artists like Larry Zox, and Frank Stella, – all moving in a new direction. Artists like Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Morris Louis, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland, Helen Frankenthaler, Larry Zox, and others often used greatly reduced references to nature, and they painted with a highly articulated and psychological use of color. In general these artists eliminated recognizable imagery. In Mountains and Sea, from 1952, (see above) a seminal work of Colorfield painting by Helen Frankenthaler the artist used the stain technique for the first time.

In Europe there was the continuation of Surrealism, Cubism, Dada and the works of Matisse. Also in Europe, Tachisme (the European equivalent to Abstract expressionism) took hold of the newest generation. Serge Poliakoff, Nicolas de Staël, Georges Mathieu, Vieira da Silva, Jean Dubuffet, Yves Klein and Pierre Soulages among others are considered important figures in post-war European painting.

Eventually abstract painting in America evolved into movements such as Neo-Dada, Color Field painting, Post painterly abstraction, Op art, hard-edge painting, Minimal art, shaped canvas painting, Lyrical Abstraction, Neo-expressionism and the continuation of Abstract expressionism. As a response to the tendency toward abstraction imagery emerged through various new movements, notably Pop art.

Realism, Landscape, Seascape, Figuration, Still-Life, Cityscape

-

George Bellows, 1924, American realism

-

Arshile Gorky, 1929–1936, pre-Abstract Expressionist figuration

-

Andrew Wyeth, Christina's World (1948), Realism

-

Edward Hopper, 1953, Cityscape

-

Milton Avery, 1958, Seascape painting

During the 1930s through the 1960s as abstract painting in America and Europe evolved into movements such as abstract expressionism, Color Field painting, Post-painterly Abstraction, Op art, hard-edge painting, Minimal art, shaped canvas painting, and Lyrical Abstraction. Other artists reacted as a response to the tendency toward abstraction allowing imagery to continue through various new contexts like the Bay Area Figurative Movement in the 1950s and new forms of expressionism from the 1940s through the 1960s. In Italy during this time, Giorgio Morandi was the foremost still life painter, exploring a wide variety of approaches to depicting everyday bottles and kitchen implements.[52] Throughout the 20th century many painters practiced Realism and used expressive imagery; practicing landscape and figurative painting with contemporary subjects and solid technique, and unique expressivity like Milton Avery, John D. Graham, Fairfield Porter, Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth, Balthus, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff, Philip Pearlstein, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Grace Hartigan, Robert De Niro, Sr., Elaine de Kooning and others. Along with Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Pierre Bonnard, Georges Braque, and other 20th-century masters.

Arshile Gorky's portrait of Willem de Kooning (above) is an example of the evolution of abstract expressionism from the context of figure painting, cubism and surrealism. Along with his friends de Kooning and John D. Graham Gorky created bio-morphically shaped and abstracted figurative compositions that by the 1940s evolved into totally abstract paintings. Gorky's work seems to be a careful analysis of memory, emotion and shape, using line and color to express feeling and nature.

Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953 (see above) is a painting by the Irish born artist Francis Bacon and is an example of Post World War II European Expressionism. The work shows a distorted version of the Portrait of Innocent X painted by the Spanish artist Diego Velázquez in 1650. The work is one of a series of variants of the Velázquez painting which Bacon executed throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, over a total of forty-five works.[53] When asked why he was compelled to revisit the subject so often, Bacon replied that he had nothing against the Popes, that he merely "wanted an excuse to use these colours, and you can't give ordinary clothes that purple colour without getting into a sort of false fauve manner."[54] The Pope in this version seethes with anger and aggression, and the dark colors give the image a grotesque and nightmarish appearance.[55] The pleated curtains of the backdrop are rendered transparent, and seem to fall through the Pope's face.[56] The figurative work of Francis Bacon, Frida Kahlo, Edward Hopper, Lucian Freud Andrew Wyeth and others served as a kind of alternative to abstract expressionism. One of the most well-known images in 20th-century American art is Wyeth's painting, Christina's World, currently in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It depicts a woman lying on the ground in a treeless, mostly tawny field, looking up at and crawling towards a gray house on the horizon; a barn and various other small outbuildings are adjacent to the house. This tempera work, done in a realist style, is nearly always on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.[57]

After World War II the term School of Paris often referred to Tachisme, the European equivalent of American Abstract expressionism and those artists are also related to Cobra. Important proponents being Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Soulages, Nicolas de Staël, Hans Hartung, Serge Poliakoff, and Georges Mathieu, among several others. During the early 1950s Dubuffet (who was always a figurative artist), and de Staël, abandoned abstraction, and returned to imagery via figuration and landscape. De Staël 's work was quickly recognised within the post-war art world, and he became one of the most influential artists of the 1950s. His return to representation (seascapes, footballers, jazz musicians, seagulls) during the early 1950s can be seen as an influential precedent for the American Bay Area Figurative Movement, as many of those abstract painters like Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Wayne Thiebaud, Nathan Oliveira, Joan Brown and others made a similar move; returning to imagery during the mid-1950s. Much of de Staël 's late work – in particular his thinned, and diluted oil on canvas abstract landscapes of the mid-1950s predicts Color Field painting and Lyrical Abstraction of the 1960s and 1970s. Nicolas de Staël's bold and intensely vivid color in his last paintings predict the direction of much of contemporary painting that came after him including Pop art of the 1960s. Milton Avery as well through his use of color and his interest in seascape and landscape paintings connected with the Color field aspect of Abstract expressionism as manifested by Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko as well as the lessons American painters took from the work of Henri Matisse.[58][59]

Pop art

Pop art in America was to a large degree initially inspired by the works of Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers, and Robert Rauschenberg. Although the paintings of Gerald Murphy, Stuart Davis and Charles Demuth during the 1920s and 1930s set the table for Pop art in America.

In New York City during the mid-1950s Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns created works of art that at first seemed to be continuations of Abstract expressionist painting. Actually their works and the work of Larry Rivers, were radical departures from abstract expressionism especially in the use of banal and literal imagery and the inclusion and the combining of mundane materials into their work. The innovations of Johns' specific use of various images and objects like chairs, numbers, targets, beer cans and the American Flag; Rivers paintings of subjects drawn from popular culture such as George Washington crossing the Delaware, and his inclusions of images from advertisements like the camel from Camel cigarettes, and Rauschenberg's surprising constructions using inclusions of objects and pictures taken from popular culture, hardware stores, junkyards, the city streets, and taxidermy gave rise to a radical new movement in American art. Eventually by 1963 the movement came to be known worldwide as Pop art.

Pop art is exemplified by artists: Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Wayne Thiebaud, James Rosenquist, Jim Dine, Tom Wesselmann and Roy Lichtenstein among others. Lichtenstein used oil and Magna paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Girl (1963), which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics' Secret Hearts #83. (Drowning Girl now is in the collection of Museum of Modern Art, New York.[60]) Also featuring thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots to represent certain colors, as if created by photographic reproduction. Lichtenstein would say of his own work: Abstract Expressionists "put things down on the canvas and responded to what they had done, to the color positions and sizes. My style looks completely different, but the nature of putting down lines pretty much is the same; mine just don't come out looking calligraphic, like Pollock's or Kline's."[61] Pop art merges popular and mass culture with fine art, while injecting humor, irony, and recognizable imagery and content into the mix. In October 1962 the Sidney Janis Gallery mounted The New Realists the first major Pop art group exhibition in an uptown art gallery in New York City. Sidney Janis mounted the exhibition in a 57th Street storefront near his gallery at 15 E. 57th Street. The show sent shockwaves through the New York School and reverberated worldwide. Earlier in the fall of 1962 a historically important and ground-breaking New Painting of Common Objects exhibition of Pop art, curated by Walter Hopps at the Pasadena Art Museum sent shock waves across the Western United States. Campbell's Soup Cans (sometimes referred to as 32 Campbell's Soup Cans) is the title of an Andy Warhol work of art (see gallery) that was produced in 1962. It consists of thirty-two canvases, each measuring 20 inches in height x 16 inches in width (50.8 x 40.6 cm) and each consisting of a painting of a Campbell's Soup can—one of each canned soup variety the company offered at the time. The individual paintings were produced with a semi-mechanised silkscreen process, using a non-painterly style. They helped usher in Pop art as a major art movement that relied on themes from popular culture. These works by Andy Warhol are repetitive and they are made in a non-painterly commercial manner.

Earlier in England in 1956 the term Pop Art was used by Lawrence Alloway for paintings that celebrated consumerism of the post World War II era. This movement rejected Abstract expressionism and its focus on the hermeneutic and psychological interior, in favor of art which depicted, and often celebrated material consumer culture, advertising, and iconography of the mass production age.[62] The early works of David Hockney whose paintings emerged from England during the 1960s like A Bigger Splash, (see above) and the works of Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, and Eduardo Paolozzi, are considered seminal examples in the movement. While in the downtown scene in New York's East Village 10th Street galleries artists were formulating an American version of Pop art. Claes Oldenburg had his storefront, and the Green Gallery on 57th Street began to show Tom Wesselmann and James Rosenquist. Later Leo Castelli exhibited other American artists including the bulk of the careers of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein and his use of Benday dots, a technique used in commercial reproduction and seen in ordinary comic books and in paintings like Drowning Girl, 1963, in the gallery above. There is a connection between the radical works of Duchamp, and Man Ray, the rebellious Dadaists – with a sense of humor; and Pop Artists like Alex Katz (whose parody of portrait photography and suburban life can be seen above), Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and the others.

Art Brut, New Realism, Bay Area Figurative Movement, Neo-Dada, Photorealism

-

Jasper Johns, 1961, Neo-Dada

-

Robert Rauschenberg, 1963, Neo-Dada

-

Jean Dubuffet, 1962, Art Brut

During the 1950s and 1960s as abstract painting in America and Europe evolved into movements such as Color Field painting, Post painterly abstraction, Op art, hard-edge painting, Minimal art, shaped canvas painting, Lyrical Abstraction, and the continuation of Abstract expressionism. Other artists reacted as a response to the tendency toward abstraction with Art brut,[63] Fluxus, Neo-Dada, New Realism, allowing imagery to re-emerge through various new contexts like Pop art, the Bay Area Figurative Movement and later in the 1970s Neo-expressionism. The Bay Area Figurative Movement of whom David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Nathan Oliveira and Richard Diebenkorn whose painting Cityscape 1, 1963 is a typical example (see above) were influential members flourished during the 1950s and 1960s in California. Although throughout the 20th century painters continued to practice Realism and use imagery, practicing landscape and figurative painting with contemporary subjects and solid technique, and unique expressivity like Milton Avery, Edward Hopper, Jean Dubuffet, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, Philip Pearlstein, and others. Younger painters practiced the use of imagery in new and radical ways. Yves Klein, Arman, Martial Raysse, Christo, Niki de Saint Phalle, David Hockney, Alex Katz, Malcolm Morley, Ralph Goings, Audrey Flack, Richard Estes, Chuck Close, Susan Rothenberg, Eric Fischl, and Vija Celmins were a few who became prominent between the 1960s and the 1980s. Fairfield Porter (see above) was largely self-taught, and produced representational work in the midst of the Abstract Expressionist movement. His subjects were primarily landscapes, domestic interiors and portraits of family, friends and fellow artists, many of them affiliated with the New York School of writers, including John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, and James Schuyler. Many of his paintings were set in or around the family summer house on Great Spruce Head Island, Maine.

Also during the 1960s and 1970s, there was a reaction against painting. Critics like Douglas Crimp viewed the work of artists like Ad Reinhardt, and declared the 'death of painting'. Artists began to practice new ways of making art. New movements gained prominence some of which are: Fluxus, Happening, Video art, Installation art Mail art, the situationists, Conceptual art, Postminimalism, Earth art, arte povera, performance art and body art among others.

Neo-Dada is also a movement that started 1n the 1950s and 1960s and was related to Abstract expressionism only with imagery. Featuring the emergence of combined manufactured items, with artist materials, moving away from previous conventions of painting. This trend in art is exemplified by the work of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, whose "combines" in the 1950s were forerunners of Pop Art and Installation art, and made use of the assemblage of large physical objects, including stuffed animals, birds and commercial photography. Robert Rauschenberg, (see untitled combine, 1963, above), Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers, John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, George Segal, Jim Dine, and Edward Kienholz among others were important pioneers of both abstraction and Pop Art; creating new conventions of art-making; they made acceptable in serious contemporary art circles the radical inclusion of unlikely materials as parts of their works of art.

Geometric abstraction, Op Art, Hard-Edge, Color field, Minimal Art, New Realism

-

Yves Klein, 1962, New Realism

-

Richard Anuszkiewicz, 1978, Op art

During the 1960s and 1970s abstract painting continued to develop in America through varied styles. Geometric abstraction, Op art, hard-edge painting, Color Field painting and minimal painting, were some interrelated directions for advanced abstract painting as well as some other new movements. Morris Louis (see gallery) was an important pioneer in advanced Colorfield painting, his work can serve as a bridge between Abstract expressionism, Colorfield painting, and Minimal Art. Two influential teachers Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann introduced a new generation of American artists to their advanced theories of color and space. Josef Albers is best remembered for his work as an Geometric abstractionist painter and theorist. Most famous of all are the hundreds of paintings and prints that make up the series Homage to the Square, (see gallery). In this rigorous series, begun in 1949, Albers explored chromatic interactions with flat colored squares arranged concentrically on the canvas. Albers' theories on art and education were formative for the next generation of artists. His own paintings form the foundation of both hard-edge painting and Op art.