Julianne Moore

Julianne Moore | |

|---|---|

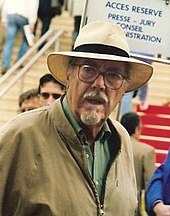

Moore at the 66th Venice International Film Festival, September 2009 | |

| Born | Julie Anne Smith December 3, 1960 Fort Bragg, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Boston University |

| Occupation(s) | Actress Children's author |

| Years active | 1983–present |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Peter Moore Smith (brother) |

| Awards | Full list |

Julianne Moore (born Julie Anne Smith; December 3, 1960) is a British-American[1] actress and children's author. Prolific in cinema since the early 1990s, Moore is active in both art house and Hollywood films. She is particularly known for her portrayals of emotionally troubled women, and has received many accolades including the Academy Award for Best Actress.

After studying theatre at Boston University, Moore began her career with a series of television roles. From 1985 to 1988, she was a regular in the soap opera As the World Turns, earning a Daytime Emmy for her performance. Her film debut was in 1990's Tales from the Darkside: The Movie, and she continued to play small roles for the next four years – including in the thriller The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992). Moore first received critical attention with Robert Altman's Short Cuts (1993), and successive performances in Vanya on 42nd Street (1994) and Safe (1995) continued this acclaim. Starring roles in the blockbusters Nine Months (1995) and The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) established her as a leading actress in Hollywood, although she continued to take supporting roles.

Moore received considerable recognition in the late 1990s and early 2000s, earning Oscar nominations for Boogie Nights (1997), The End of the Affair (1999), Far from Heaven (2002; winning the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival), and The Hours (2002; winning the Silver Bear for Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival); in the first of these she played a 1970s pornography actress, while the other three featured her as an unhappy, mid-20th century housewife. She also had success with the films The Big Lebowski (1998), Magnolia (1999), Hannibal (2001), Children of Men (2006), A Single Man (2009), and The Kids Are All Right (2010), and won a Primetime Emmy and Golden Globe for her portrayal of Sarah Palin in the television film Game Change (2012). The year 2014 was key for Moore, as she gave an Oscar-winning performance as an Alzheimer's patient in Still Alice, was named Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival for the David Cronenberg black comedy film Maps to the Stars, and joined the popular Hunger Games series.

In addition to acting, Moore has written a series of children's books about the character "Freckleface Strawberry". She is married to the director Bart Freundlich, with whom she has two children.

Early life

Moore was born Julie Anne Smith on December 3, 1960,[2] at the Fort Bragg army installation in North Carolina.[3] Her father, Peter Moore Smith,[4] was a paratrooper in the United States Army,[5] who later attained the rank of colonel and became a military judge.[6] Her mother, Anne (née Love; 1940–2009),[7] was a psychologist and social worker from Greenock, Scotland, who emigrated to the United States as a child in 1950.[4] Moore has a younger sister, Valerie, and a younger brother, the novelist Peter Moore Smith.[4][8][9] She considers herself half Scottish and claimed British citizenship in 2011 to honor her deceased mother.[3][10] She also has Irish and English ancestry.[11]

Moore frequently moved around the United States as a child, due to her father's occupation. She was close to her family as a result, but has said she never had the feeling of coming from one particular place.[2][6] The family lived in multiple locations, including Alabama, Georgia, Texas, Panama, Nebraska, Alaska, New York, and Virginia, and Moore attended nine different schools.[12] The constant relocating made her an insecure child, and she struggled to establish friendships.[3][6] Despite these difficulties, Moore later remarked that an itinerant lifestyle was beneficial to her future career: "When you move around a lot, you learn that behavior is mutable. I would change, depending on where I was ... It teaches you to watch, to reinvent, that character can change."[13]

When Moore was 16, the family moved from Falls Church, Virginia, where she had been attending J.E.B. Stuart High School, to Frankfurt, Germany, where she attended Frankfurt American High School.[6][12] She was clever, studious politically correct, a self-proclaimed "good girl", and she planned to become a doctor.[5] She had never considered performing, or even attended the theatre,[12] but she was an avid reader and it was this hobby that led her to begin acting at the school.[2][14] She appeared in several plays, including Tartuffe and Medea, and with the encouragement of her English teacher she chose to pursue a theatrical career.[15] Moore's parents supported her decision, but asked that she train at university to provide the added security of a college degree.[5] She was accepted to Boston University and graduated with a BFA in Theatre in 1983.[15]

Acting career

Early roles (1983–93)

"There was already a Julie Smith, a Julie Anne Smith, there was everything. My father's middle name is Moore; my mother's name is Anne. So I just slammed the Anne onto the Julie. That way, I could use both of their names and not hurt anyone's feelings. But it's horrible to change your name. I'd been Julie Smith my whole life, and I didn't want to change it."

Moore moved to New York City after graduating, and worked as a waitress.[17] After registering a stage name with Actors' Equity,[16] she began her career in 1983 with off-Broadway theatre.[18] Her first screen role came in 1984, in an episode of the soap opera The Edge of Night.[19] Her break came the following year, when she joined the cast of As the World Turns. Playing the dual roles of half-sisters Frannie and Sabrina Hughes, the intensive work provided an important learning experience for Moore, who looks back on the job fondly: "I gained confidence and learned to take responsibility", she has said.[15] Moore appeared on the show until 1988, when she won a Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Ingenue in a Drama Series.[20][21] Before leaving As the World Turns, she had a role in the 1987 CBS miniseries I'll Take Manhattan.[12] Once she had finished on the soap opera, she turned to the stage to play Ophelia in a Guthrie Theater production of Hamlet opposite Željko Ivanek.[16][22][23] The actress sporadically returned to television over the next three years, appearing in the TV movies Money, Power, Murder (1989), The Last to Go (1991), and Cast a Deadly Spell (1991).[24]

In 1990, Moore began working with stage director Andre Gregory on a workshop theatre production of Chekhov's Uncle Vanya. Described by Moore as "one of the most fundamentally important acting experiences I ever had",[12] the group spent four years exploring the text and giving intimate performances to friends.[25] The same year, Moore made her cinematic debut in Tales from the Darkside: The Movie, playing a mummy's victim.[26] Her next film role did not come until 1992, but introduced her to a wide audience. The thriller The Hand That Rocks the Cradle—in which she played the main character's friend—was number one at the US box office, and Moore caught the attention of several critics with her performance.[16][27] She followed it the same year with the comedy The Gun in Betty Lou's Handbag. Moore continued to play supporting roles throughout 1993, firstly appearing in the Madonna flop Body of Evidence,[28] which she later regretted,[16] and then in the romantic comedy Benny & Joon with Johnny Depp. She also appeared briefly as a doctor in one of the year's biggest hits, the Harrison Ford thriller The Fugitive.[16][29]

Rise to prominence (1993–97)

The filmmaker Robert Altman saw Moore in Uncle Vanya, and was sufficiently impressed to cast her in his next project: the ensemble drama Short Cuts (1993). Moore was pleased to work with him, as it was Altman who had given her an appreciation for cinema when she saw his 1977 film 3 Women in college.[30] Playing artist Marian Wyman was an experience she found difficult, as she was a "total unknown" surrounded by established actors, but it proved to be Moore's breakout role.[31][32] Variety magazine described her as "arresting", and noted that her monologue, delivered naked from the waist down, would "no doubt be the most discussed scene" of the film.[33] Short Cuts was critically acclaimed, and received awards for Best Ensemble Cast at the Venice Film Festival and the Golden Globe Awards. Moore received an individual nomination for Best Supporting Female at the Independent Spirit Awards, while the monologue earned her a degree of notoriety.[34][35][36]

Short Cuts was one of a trio of successive film appearances that boosted Moore's reputation.[15] It was followed in 1994 with Vanya on 42nd Street, a filmed version of her ongoing Vanya production, directed by Louis Malle.[25] Moore's performance of Yelena was described as "simply outstanding" by Time Out,[37] and she won the Boston Society of Film Critics award for Best Actress.[38] Moore was then given her first leading role, playing an unhappy suburban housewife who develops multiple chemical sensitivity in Todd Haynes' low-budget film Safe (1995). She had to lose a substantial amount of weight for the role, which made her ill and she vowed never to change her body for a film again.[39] In their review, Empire magazine writes that Safe "first established [Moore's] credentials as perhaps the finest actress of her generation".[40] The film historian David Thomson later described it as "one of the most arresting, original and accomplished films of the 1990s",[5] and the performance earned Moore an Independent Spirit Award nomination for Best Actress.[41] Reflecting on these three roles, Moore has said, "They all came out at once, and I suddenly had this profile. It was amazing."[15]

Moore's next appearance was a supporting role in the comedy–drama Roommates (1995), playing the wife of Peter Falk. Her following film, Nine Months (1995), was crucial in establishing her as a leading lady in Hollywood.[3] The romantic comedy, directed by Chris Columbus and co-starring Hugh Grant, was poorly reviewed but a box office success and remains one of her highest grossing films.[42][43][44] Her next release was also a Hollywood production, as Moore appeared alongside Sylvester Stallone and Antonio Banderas in the thriller Assassins (1995). Despite negativity from critics, the film earned $83.5 million worldwide.[45][46] Moore's only appearance of 1996 was as the artist Dora Maar in the Merchant Ivory film Surviving Picasso, which met with poor reviews.[47]

A key point in Moore's career came when she was cast by Steven Spielberg to star as paleontologist Dr. Sarah Harding in The Lost World: Jurassic Park—the sequel to his 1993 blockbuster Jurassic Park.[3] Filming the big-budget production was a new experience for Moore, and she has said she enjoyed herself "tremendously".[10] It was a physically demanding role, with the actress commenting, "There was so much hanging everywhere. We hung off everything available, plus we climbed, ran, jumped off things ... it was just non-stop."[48] The Lost World (1997) finished as one of the ten highest-grossing films in history to that point,[39] and was pivotal in making Moore a sought-after actress: "Suddenly I had a commercial film career", she has said.[3] The Myth of Fingerprints was her second appearance of 1997, where she met her future husband in director Bart Freundlich.[2] Later that year, she made a cameo appearance in the dark comedy Chicago Cab.[49]

Widespread recognition (1997–2002)

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw Moore achieve significant industry recognition. Her first Academy Award nomination came for the critically acclaimed[50] Boogie Nights (1997), which centers on a group of individuals working in the 1970s pornography industry. Director Paul Thomas Anderson was not a well known figure before its production, with only one feature credit to his name, but Moore agreed to the film after being impressed with his "exhilarating" script.[2][12] The ensemble piece featured Moore as Amber Waves, a leading porn actress and mother-figure who longs to be reunited with her real son. Martyn Glanville of the BBC commented that the role required a mixture of confidence and vulnerability, and was impressed with Moore's effort.[51] Time Out called the performance "superb",[52] while Janet Maslin of The New York Times found it "wonderful".[53] Alongside her Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, Moore was nominated at the Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild awards, and several critics groups named her a winner.[54]

Moore followed her success in Boogie Nights with a role in the Coen brothers' dark comedy The Big Lebowski (1998). The film was not a hit at the time of release but subsequently became a cult classic.[55] Her role was Maude Lebowski, a feminist artist and daughter of the eponymous character who becomes involved with "The Dude" (Jeff Bridges, the film's star). At the end of 1998, Moore had a flop with Gus Van Sant's Psycho, a remake of the classic Alfred Hitchcock film of the same name.[26] She played Lila Crane in the film, which received poor reviews[56] and is described by The Guardian as one of her "pointless" outings.[39] The review in Boxoffice magazine regretted that "a group of enormously talented people wasted several months of their lives" on the film.[57]

After reuniting with Robert Altman for the dark comedy Cookie's Fortune (1999), Moore starred in An Ideal Husband—Oliver Parker's adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play. Set in London at the end of the 19th century, her performance of Mrs. Laura Cheverly earned a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy.[58] She was also nominated in the Drama category that year for her work in The End of the Affair (1999). Based on the novel by Graham Greene, Moore played opposite Ralph Fiennes as an adulterous wife in 1940s Britain. The critic Michael Sragow was full of praise for her work, writing that her performance was "the critical element that makes [the film] necessary viewing."[59] Moore received her second Academy Award nomination for the role—her first for Best Actress—as well as nominations at the British Academy (BAFTA) and Screen Actors Guild (SAG) awards.[60]

In between her two Golden Globe-nominated performances, Moore was seen in A Map of the World, supporting Sigourney Weaver, as a bereaved mother.[24] Her fifth and final film of 1999 was the acclaimed drama Magnolia,[61] a "giant mosaic" chronicling the lives of multiple characters over one day in Los Angeles.[62] Paul Thomas Anderson, in his follow-up to Boogie Nights, wrote a role specifically for Moore. His primary objective was to "see her explode", and he cast her as a morphine-addicted wife.[62] Moore has said it was a particularly difficult role, but she was rewarded with a SAG nomination.[12][41] She was subsequently named Best Supporting Actress of 1999 by the National Board of Review, in recognition of her three performances in Magnolia, An Ideal Husband, and A Map of the World.[63]

Apart from a cameo role in the comedy The Ladies Man, Moore's only other appearance in 2000 was in a short-film adaptation of Samuel Beckett's play Not I.[64] In early 2001, she appeared as FBI Agent Clarice Starling in Hannibal, a sequel to the Oscar winning film The Silence of the Lambs. Jodie Foster had declined to reprise the role, and director Ridley Scott eventually cast Moore over Angelina Jolie, Cate Blanchett, Gillian Anderson, and Helen Hunt.[16] The change in actress received considerable attention from the press, but Moore claimed she was not interested in upstaging Foster.[16] Despite negative reviews,[65] Hannibal earned $58 million in its opening weekend and finished as the tenth highest-grossing film of the year.[66][67] In three more 2001 releases, Moore starred with David Duchovny in the science fiction–comedy Evolution, appeared in her husband's dramatic film World Traveler, and acted with Kevin Spacey, Judi Dench, and Cate Blanchett in The Shipping News. All three films were poorly received.[68][69][70]

The year 2002 marked a high point in Moore's career,[71] as she became the ninth performer to be nominated for two Academy Awards in the same year.[72] She received a Best Actress nomination for the melodrama Far from Heaven, in which she played a 1950s housewife whose world is shaken when her husband reveals he is gay. The role was written specifically for her by Todd Haynes, the first time the pair had worked together since Safe, and Moore described it as "a very, very personal project ... such an incredible honor to do."[73] David Rooney of Variety praised her "beautifully gauged performance" of a desperate woman "buckling under social pressures and putting on a brave face".[74] Manohla Dargis of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "what Moore does with her role is so beyond the parameters of what we call great acting that it nearly defies categorization."[75] The role won Moore the Best Actress award from 19 different organizations, including the Venice Film Festival and the National Board of Review.[76]

Moore's second Oscar nomination that year came for The Hours, which she co-starred in with Nicole Kidman and Meryl Streep. She again played a troubled 1950s housewife, prompting Kenneth Turan to write that she was "essentially reprising her Far from Heaven role".[77] Moore said it was an "unfortunate coincidence" that the similar roles came at the same time, and claimed that the characters had differing personalities.[78] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone called the performance "wrenching",[79] while Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian praised a "superbly controlled, humane performance".[80] The Hours was nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Moore also received BAFTA and SAG Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress, and was jointly awarded the Silver Bear for Best Actress with Kidman and Streep at the Berlin Film Festival.[81]

Established actress (2003–09)

Moore did not make any screen appearances in 2003, but returned in 2004 with three films. There was no success in her first two ventures of the year: Marie and Bruce, a dark comedy co-starring Matthew Broderick, did not get a cinematic release;[82] Laws of Attraction followed, where she played opposite Pierce Brosnan in a courtroom-based romantic comedy, but the film was panned by critics.[83] Commercial success returned to Moore with The Forgotten, a psychological thriller in which she played a mother who is told her dead son never existed. Although the film was unpopular with critics, it opened as the US box office number one.[84][85]

In 2005, Moore worked with her husband for the third time in the comedy Trust the Man,[17] and starred in the true story of a 1950s housewife, The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio.[86] Her first release of 2006 was Freedomland, a mystery co-starring Samuel L. Jackson. The response was overwhelmingly negative[87] but her follow-up, Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men (2006), was highly acclaimed.[88] Moore had a supporting role in the dystopian drama, playing the leader of an activist group. It is listed on Rotten Tomatoes as one of the best reviewed films of her career, and was named by Peter Travers as the second best film of the decade.[89][90]

Moore made her Broadway debut in the world premiere of David Hare's play The Vertical Hour. The production, directed by Sam Mendes and co-starring Bill Nighy, opened in November 2006. Moore played the role of Nadia, a former war correspondent who finds her views on the 2003 invasion of Iraq challenged.[91] Ben Brantley of The New York Times was unenthusiastic about the production, and described Moore as miscast: in his opinion, she failed to bring the "tough, assertive" quality that Nadia required.[92] David Rooney of Variety criticized her "lack of stage technique", adding that she appeared "stiffly self-conscious".[91] Moore later confessed that she found performing on Broadway difficult and had not connected with the medium, but was glad to have experimented with it.[10] The play closed in March 2007 after 117 performances.[93]

Moore played an FBI agent for the second time in Next (2007), a science fiction action film co-starring Nicolas Cage and Jessica Biel. Based on a short story by Philip K. Dick, the response from critics was highly negative.[94] Manhola Dargis wrote, "Ms. Moore seems terribly unhappy to be here, and it's no wonder."[95] The actress has since described it as her worst film.[8] Next was followed by Savage Grace (2007), the true story of Barbara Daly Baekeland—a high-society mother whose Oedipal relationship with her son ended in murder. Moore was fascinated by the role,[32] but the film was considered controversial for its explicit depiction of incest.[96] She told an interviewer, "Obviously you do have some trepidation about that kind of stuff, but it's not being celebrated. This is presented as a tragedy."[97] Savage Grace had a limited release, and received predominantly negative reviews.[98][99] Peter Bradshaw, however, called it a "coldly brilliant and tremendously acted movie."[100]

I'm Not There (2007) saw Moore work with Todd Haynes for the third time. The film explored the life of Bob Dylan, with Moore playing a character based on Joan Baez.[101] In 2008, she starred with Mark Ruffalo in Blindness, a dystopian thriller from the director Fernando Meirelles. The film was not widely seen, and critics were generally unenthusiastic.[102][103] Moore was not seen on screen again until late 2009, with three new releases. She had a supporting role in The Private Lives of Pippa Lee, and then starred in the erotic thriller Chloe with Amanda Seyfried and Liam Neeson.[24] Shortly afterwards, she appeared in the well-received drama A Single Man.[104] Set in 1960s Los Angeles, the film starred Colin Firth as a homosexual professor who wishes to end his life. Moore played his best friend, "a fellow English expat and semi-alcoholic divorcee",[105] a character that Tom Ford, the film's writer–director, created with her in mind.[10] Leslie Felperin of Variety commented that it was Moore's best role in "some time", and was impressed by the "extraordinary emotional nuance" of the performance.[106] A Single Man was named one of the 10 best films of the year by the American Film Institute,[107] and Moore received a fifth Golden Globe nomination for her work.[41]

Television and comedy (2010–13)

Moore returned to television for the first time in 18 years when she played a guest role in the fourth season of 30 Rock. She appeared in five episodes of the Emmy-winning comedy, playing Nancy Donovan, a love interest for Alec Baldwin's character Jack Donaghy.[108] She later appeared in the series finale in January 2013.[109] She also returned to As the World Turns, making a cameo appearance as Frannie Hughes when the show was cancelled in 2010.[15] Her first big-screen appearance of the new decade was Shelter (2010), a film described as "heinous" by Tim Robey of The Telegraph.[110] The psychological thriller received negative reviews and did not have a US release until 2013 (retitled 6 Souls).[111]

Moore next starred with Annette Bening in the independent film[112] The Kids Are All Right (2010), a comedy–drama about a lesbian couple whose teenage children locate their sperm donor. The role of Jules Allgood was written for her by writer–director Lisa Cholodenko, who felt that Moore was the right age, adept at both drama and comedy, and confident with the film's sexual content.[113] The actress was drawn to the film's "universal" depiction of married life, and committed to the project in 2005.[113] The Kids Are All Right was widely acclaimed, eventually garnering an Oscar nomination for Best Picture.[114][115] The critic Betsy Sharkey praised Moore's performance of Jules, who she called an "existential bundle of unrealized need and midlife uncertainty", writing, "There are countless moments when the actress strips bare before the camera—sometimes literally, sometimes emotionally ... and Moore plays every note perfectly."[116] The Kids Are All Right earned Moore a sixth Golden Globe Award nomination and a second BAFTA nomination for Best Actress.[115]

"I read her biography, books that were written about her and the election, listened to her voice endlessly on my iPod and worked with a vocal coach. I basically immersed myself in the study of her, and attempted to authenticate her as completely as possible ... It was tremendously challenging to represent someone so very well-known and idiosyncratic, and so recently in the public eye."

For her next project, Moore actively looked for another comedy.[118] She had a supporting role in Crazy, Stupid, Love, playing the estranged wife of Steve Carell, which was favorably reviewed and earned $142.8 million worldwide.[119][120] Moore was not seen on screens again until March 2012, with a performance that received considerable praise and recognition. She starred in the HBO television film Game Change, a dramatization of Sarah Palin's 2008 campaign to become Vice President. Portraying a well-known figure was something she found challenging; in preparation, she conducted extensive research and worked with a dialect coach for two months.[121] Although the response to the film was mixed, critics were highly appreciative of Moore's performance.[122] For the first time in her career, she received a Golden Globe, a Primetime Emmy, and a SAG Award.[123]

Moore made two film appearances in 2012. The drama Being Flynn, in which she supported Robert De Niro, had a limited release.[124] Greater success came for What Maisie Knew, the story of a young girl caught in the middle of her parents' divorce. Adapted from Henry James's novel and updated to the 21st century, the drama earned near-universal critical praise.[125] The role of Susanna, Maisie's rock-star mother, required Moore to sing on camera, which was a challenge she embraced despite finding it embarrassing.[126] She called Susanna a terrible parent, but said the role did not make her uncomfortable as she fully compartmentalized the character: "I know that that's not me".[126][127]

Following her well-received performance in What Maisie Knew,[125] Moore began 2013 with a supporting role in Joseph Gordon-Levitt's comedy Don Jon, playing an older woman who helps the title character to appreciate his relationships. Reviews for the film were favorable,[128] and Mary Pols of Time magazine wrote that Moore was a key factor in its success.[129] Her next appearance was a starring role in the comedy The English Teacher (2013), but this outing was poorly received and earned little at the box office.[130] In October 2013, she played the demented mother Margaret White in Carrie, an adaptation of Stephen King's horror novel.[131] Coming 37 years after Brian De Palma's well-known take on the book,[132] Moore stated that she wanted to make the role her own. By drawing on King's writing rather than the 1976 film,[133] Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that she managed to "[suggest] a history – one never told, just hinted at – of serious damage in [Margaret's] past."[131] The film was a box office success, but was generally considered an unsuccessful and unnecessary adaptation.[134][135]

Awards success (2014–present)

At 53 years old, Moore enjoyed a considerable degree of critical and commercial success in 2014. Her first release of the year came alongside Liam Neeson in the action–thriller Non-Stop, set aboard an airplane. The response to the film was mixed but it earned $223 million worldwide.[136][137] She followed this by winning the Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival for her portrayal of Havana Segrand, an ageing actress receiving psychotherapy in David Cronenberg's black comedy Maps to the Stars.[138] Described by The Guardian as a "grotesque, gaudy and ruthless" character, Moore based her role on "an amalgam of Hollywood casualties she ha[d] encountered" and drew upon her early experiences in the industry.[139] Peter Debruge of Variety criticized the film but found Moore to be "incredible" and "fearless" in it.[140] Moore's success at Cannes made her the second actress in history, after Juliette Binoche, to win at the "Big Three" film festivals (Cannes, Venice, and Berlin).[141] She also received a Golden Globe nomination for the performance.[142]

In the third instalment of the popular Hunger Games film series, Mockingjay – Part 1, Moore played the supporting role of President Alma Coin, the leader of a rebellion against The Capitol. The film ranks as her highest-grossing to date.[44] Her final appearance of 2014 was one of the most acclaimed of her career. In the drama Still Alice, Moore played the leading role of a linguistic professor diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer's disease.[143] She spent four months training for the film, by watching documentaries on the disease and interacting with patients at the Alzheimer's Association.[144] Critic David Thomson wrote that Moore was "extraordinary at revealing the gradual loss of memory and confidence", while according to Kenneth Turan she was "especially good at the wordless elements of this transformation, allowing us to see through the changing contours of her face what it is like when your mind empties out."[145][146] Several critics commented that it was her finest performance to date,[147] and Moore was awarded with the Oscar, Golden Globe, SAG, and BAFTA for Best Actress.

Moore began 2015 by starring as an evil queen in Seventh Son, a poorly received fantasy–adventure film, co-starring Jeff Bridges.[148] As of February 2015, she has three upcoming projects. In November, she will reprise her role of Alma Coin in The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2.[149] Her other roles include Freeheld, a drama based on a true story about a detective and her same-sex partner (with Ellen Page),[150] and the romantic comedy Maggie's Plan (with Greta Gerwig).[151]

Reception and acting style

Moore has been described in the media as one of the most talented and accomplished actresses of her generation.[2][5][40] As a woman in her 50s, she is unusual in being an older actress who continues to work regularly and in prominent roles.[152] She enjoys the variety of appearing in both low-budget independent films and large-scale Hollywood productions.[10][39] In 2004, an IGN journalist wrote of this "rare ability to bounce between commercially viable projects like Nine Months to art house masterpieces like Safe unscathed", adding, "She is respected in art houses and multiplexes alike."[153] She is noted for playing in a range of material,[5][39][154] and the director Ridley Scott, who worked with Moore on Hannibal, has praised her versatility.[16] In October 2013, Moore was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[14] She has been included in People magazine's annual beauty lists on four occasions (1995, 2003, 2008, 2013).[155]

"I never care that [my characters] are 'strong'. I never care that they're even affirmative. I look for that thing that's human and recognizable and emotional. You know, we're not perfect, we're not heroic, we're not in control. We're our own worst enemies sometimes, we cause our own tragedies ... that's the stuff that I think is really compelling."

Moore is particularly known for playing troubled women, and specializes in "ordinary women who suppress powerful emotions".[2][97][154] Oliver Burkeman of The Guardian writes that her characters are typically "struggling to maintain a purchase on normality in the face of some secret anguish or creeping awareness of failure".[17] Suzie Mackenzie, also of The Guardian, has identified a theme of "characters in a state of alienation ... women who have forgotten or lost themselves. People whose identity is a question."[5] Her performances often include small hints at emotional turmoil, until there comes a point when the character breaks.[6][17][156] The journalist Kira Cochrane has identified this as a "trademark moment" in many of her best films,[6] while it has led Burkeman to call her the "queen of the big-screen breakdown".[17] "When she does finally crack," writes journalist Simon Hattenstone, "it's a sight to behold: nobody sobs from the soul quite like Moore."[8] Ben Brantley of The New York Times has praised Moore's ability to subtly reveal the inner-turmoil of her characters, writing that she is "peerless" in her "portraits of troubled womanhood."[156] When it comes to more authoritative roles, Brantley believes she is "a bit of a bore".[156] "Emotional nakedness is Ms. Moore's specialty," he says, "and it's here that you sense the magic she is capable of."[92]

An interest in portraying "actual human drama" has led Moore to these roles.[10][12] She is particularly moved by the concept of an individual repressing their troubles and striving to maintain dignity.[2] Parts where the character achieves an amazing feat are of little interest to her, because "we're just not very often in that position in our lives."[17] Early in her career, Moore established a reputation for pushing boundaries,[6] and she continues to be praised for her "fearless" performances and for taking on difficult roles.[10][97][157] When asked if there are any roles she has avoided, she replied, "Nothing within the realm of human behaviour".[6] She is known for her willingness to perform nude and appear in sex scenes,[8][13] although has said she will only do so if she feels it fits the role.[10][157]

Regarding her approach to acting, Moore said in a 2002 interview that she leaves 95 percent of the performance to be discovered on set: "I want to have a sense of who a character is, and then I want to get there and have it happen to me on camera." The aim, she said, is to "try to get yourself in a position to let the emotion [happen] to you, that you don't bring the emotion to it ... and when it happens, there's nothing better or more exciting or more rewarding."[12]

Writing

| External image | |

|---|---|

Alongside her acting work, Moore has established a career as a children's author. Her first book, Freckleface Strawberry, was published in October 2007 and became a New York Times Best Seller.[158][159] Described by Time Out as a "simple, sweet and semi-autobiographical narrative", it tells the story of a girl who wishes to be rid of her freckles but eventually accepts them.[160] Moore decided to write the book when her young son began disliking aspects of his appearance; she was reminded of her own childhood, when she was teased for having freckles and called "Freckleface Strawberry" by other children.[161] Moore has written two follow-up books in the series: Freckleface Strawberry and the Dodgeball Bully was published in 2009, and Freckleface Strawberry: Best Friends Forever in 2011.[162] Both carry the message that children can overcome their own problems.[163]

Freckleface Strawberry has been adapted into a musical, written by Rose Caiola and Gary Kupper, which premiered at the New World Stages, New York, in October 2010.[164] Moore had an input in the production, particularly through requesting that it retain the book's young target audience.[165] The show has since been licensed and performed at several venues, which she calls "extremely gratifying and extremely flattering".[163]

Moore's fourth children's book was released in September 2013, separate from the Freckleface Strawberry series. Titled My Mom is a Foreigner, But Not to Me, it is based on her experiences of growing up with a mother from another country.[166][167] The book had a negative reception from Publishers Weekly and Kirkus Reviews; while recognizing it as well-intentioned, Moore's use of verse and rhyme was criticised.[168] In November 2013, Moore signed a five-book deal with Random House publishers. Continuing with the Freckleface Strawberry series, the new books will be aimed at beginning readers.[169] The first is due for release in July 2015.[18]

Personal life

Actor and stage director John Gould Rubin was Moore's first husband, whom she met in 1984 and married two years later.[15] They separated in 1993,[5] and their divorce was finalized in August 1995.[5][15] "I got married too early and I really didn't want to be there", she has since explained.[3] Moore began a relationship with Bart Freundlich, her director on The Myth of Fingerprints, in 1996.[2] The couple have a son, Caleb (born December 1997) and a daughter, Liv (born April 2002).[170] They wed in August 2003 and live in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City.[15] Moore has commented, "We have a very solid family life, and it is the most satisfying thing I have ever done."[32] She tries to keep her family close when working and picks material that is practical for her as a parent.[2][6]

Moore is politically liberal[8] and supported Barack Obama at the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections.[32][171] She is a pro-choice activist and sits on the board of advocates for Planned Parenthood.[17][32] She is also a campaigner for gay rights[6] and gun control,[18] and since 2008 she has been an Artist Ambassador for Save the Children.[172] Moore is an atheist;[18] when asked on Inside the Actors Studio what God might say to her upon arrival at heaven, she gave God's response as, "Well I guess you were wrong, I do exist."[12]

Moore has said she finds little value in the concept of celebrity and is concerned with living a "normal" life.[5][17] Upon meeting her, the journalist Suzie Mackenzie described Moore as "the most unostentatious of stars",[5] and she attracts little gossip or tabloid attention.[17] She is humble about her profession, saying she is "just a person with a job",[17] and casual in her appearance.[8][32] Known for maintaining a natural image, Moore has spoken out against botox and plastic surgery.[3][157]

Filmography

As of the start of 2015, Moore has appeared in 61 films, four television movies, and four television series. Her most acclaimed films, according to review-aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, include Short Cuts (1993), Children of Men (2006), The Kids Are All Right (2010), Boogie Nights (1997), Far from Heaven (2002), Vanya on 42nd Street (1994), What Maisie Knew (2012), Still Alice (2014), Safe (1995), A Single Man (2009), and Magnolia (2000).[89] Her films that have earned the most at the box office are The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 (2014), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), Hannibal (2001), Non-Stop (2014), The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992), Crazy, Stupid, Love. (2011), Nine Months (1995), The Forgotten (2004), The Hours (2002), Evolution (2001), and Carrie (2013).[44]

Awards and nominations

Moore has received six Academy Award nominations, eight Golden Globe nominations, seven SAG nominations, and four BAFTA nominations. From these, she has won an Academy Award, two Golden Globes, a BAFTA, and two SAG Awards; she also has a Primetime Emmy and a Daytime Emmy. In addition, she has been named Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival, Berlin Film Festival, and Venice Film Festival – the fourth person, and second female, in history to achieve this.[141] Her recognized roles came in As the World Turns, Boogie Nights, An Ideal Husband, The End of the Affair, Magnolia, Far From Heaven, The Hours, A Single Man, The Kids Are All Right, Game Change, Maps to the Stars, and Still Alice.[173]

Published works

- Moore, Julianne (2007). Freckleface Strawberry. Illustrated by LeUyen Pham. New York: Bloomsbury Juvenile US. ISBN 978-1-59990-107-7.

- Moore, Julianne (2009). Freckleface Strawberry And The Dodgeball Bully. Illustrated by LeUyen Pham. New York: Bloomsbury Juvenile US. ISBN 978-1-59990-316-3.

- Moore, Julianne (2011). Freckleface Strawberry Best Friends Forever. Illustrated by LeUyen Pham. New York: Bloomsbury Juvenile US. ISBN 978-1-59990-782-6.

- Moore, Julianne (2013). My Mom Is a Foreigner, But Not to Me. Illustrated by Meilo So. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-0792-9.

- Moore, Julianne (2015). Freckleface Strawberry: Backpacks! (Step into Reading). Illustrated by LeUyen Pham. New York: Random House Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0385391948.

- Moore, Julianne (2015). Freckleface Strawberry: Lunch, or What's That? (Step into Reading). Illustrated by LeUyen Pham. New York: Random House Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0385391917.

References

- ^ Simon Hattenstone, Julianne Moore: 'Can we talk about something else now?' The Gurardian, 10 August, 2013

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Summerscale, Kate (October 13, 2007). "Julianne Moore: beneath the skin". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lipworth, Elaine (August 27, 2011). "Julianne Moore: still fabulous at 50, interview". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Anne Love Smith Obituary". The Washington Post. May 3, 2009. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cochrane, Kira (October 28, 2010). "Julianne Moore: 'I'm going to cry. Sorry'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ "Anne Love Smith Obituary". washingtonpost.com. May 3, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Hattenstone, Simon (August 10, 2013). "Julianne Moore: 'Can we talk about something else now?'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Julianne Moore's Bookshelf". O, The Oprah Magazine. December 2002. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rees, Jasper (July 24, 2010). "Q&A: Actress Julianne Moore". The Arts Desk. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ http://highlife.ba.com/News-And-Blogs/On-The-Road/Notes-from-a-traveller-Julianne-Moore.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Episode 7, Julianne Moore". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 9. December 22, 2002. Bravo. Stated by Moore in this interview.

- ^ a b Hirschberg, Lynn (February 25, 2010). "Julianne of the Spirits". T Magazine. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b "Julianne Moore gets star on Hollywood 'Walk of Fame'". Yahoo!. October 4, 2013. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rozen, Leah (April 2012). "Moore than Meets the Eye". More. pp. 72–75; 88.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rochlin, Margy (February 11, 2001). "FILM; Hello Again, Clarice, But You've Changed". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Burkeman, Oliver (August 26, 2006). "Unravelling Julianne". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 18, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Galloway, Stephen (January 28, 2015). "Julianne Moore Believes in Therapy, Not God (And Definitely Gun Control)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ "Julianne Moore – Biography". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Julianne Moore confirmed for appearance on 'As the World Turns'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ Waldman, Alison (April 2, 2010). "Julianne Moore Returns to 'As the World Turns' on Monday". AOL. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Alec Baldwin (December 8, 2014). "Here's the Thing" (Podcast). WNYC. 12 minutes in.

- ^ "Hamlet 1988 cast list". Guthrie Theater. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Julianne Moore". British Film Institute. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Taylor, Charles (February 24, 2012). "'Vanya,' Theater and Art of Being". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Morales, Tatiana (February 11, 2009). "Julianne Moore On Being A 'Winner'". CBS. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ King, Andrea (January 17, 1992). "Nanny-from-hell Thriller 'Cradle' Surpasses 'Hook'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Metz, Allen; Benson, Carol (2000). The Madonna Companion: Two Decades of Commentary. Schirmer Books. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8256-7194-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fox, David J. (September 8, 1993). "Labor Day Weekend Box Office : 'The Fugitive' Just Keeps on Running". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Haskell, Molly (August 2010). "Julianne". Town & Country. pp. 79–82.

- ^ Haramis, Nick (March 2012). "Julie and Julianne". BlackBook. pp. 50–57.

- ^ a b c d e f Larocca, Amy (May 9, 2008). "Julianne Moore: Portrait of a Lady". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (September 6, 1993). "Reviews – Short Cuts". Variety. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Shorts Cuts – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Short Cuts (1993) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ Neal, Rome (November 8, 2002). "More Risks For Julianne Moore". CBS. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ "Vanya on 42nd Street". Time Out London. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "Past Award Winners". Boston Society of Film Critics. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Ellison, Michael (August 13, 1999). "Less is Moore". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b "Empire's Safe Movie Review". Empire. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Julianne Moore Bio". Focus Features. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Nine Months". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Nine Months (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Julianne Moore Movie Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "Assassins (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ "Assassins (1995)". Sylvester Stallone Online. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ "Surviving Picasso". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ "Moore, Julianne: The Lost World". Urban Cinefile. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel (March 8, 2006). "Chicago Cab". Emanuel Levy. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ "Boogie Nights". Metacritic. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Glanville, Martyn (June 22, 2001). "Boogie Nights (1997)". BBC. Archived from the original on December 31, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ "Boogie Nights". Time Out London. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (October 8, 1997). "Boogie Nights (1997)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "Boogie Nights (1997) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Rohrer, Finlo (October 10, 2008). "Is The Big Lebowski a cultural milestone?". BBC. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ "Psycho (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ Kerrigan, Mike (December 4, 1998). "Psycho". Boxoffice. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "An Ideal Husband (1999) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (December 3, 1999). "The End of the Affair". Salon. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "The End of the Affair (1999) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Berra, John (2010). American Independent. Intellect Books. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-84150-368-4.

- ^ a b Patterson, John (March 10, 2000). "Magnolia maniac". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ "Awards for 1999". National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ "Not I". Beckett on Film. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ "Hannibal". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Box Office: Hannibal Takes Record-Sized Bite". ABC News. February 11, 2001. Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "2001 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "Evolution (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "World Traveler (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "The Shipping News (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ Fischer, Paul (November 2, 2002). "Julianne Moore's Far From Heaven". Film Monthly. Archived from the original on October 18, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Two in One Acting". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 10, 2009 suggested (help) - ^ "Julianne Moore, Far From Heaven, interviewed by David Michaels". BBC. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Rooney, David (September 2, 2002). "Far From Heaven". Variety. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (November 8, 2002). "MOVIE REVIEW; Tears without apology; With a nod to Douglas Sirk, 'Far From Heaven' deftly updates '50s melodramas". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2002. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Far From Heaven (2002) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (September 2, 2002). "The year of short memories". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Murray, Rebecca; Topel, Fred. "Julianne Moore Talks About "Far From Heaven"". About.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Travers, Peter (January 24, 2003). "The Hours". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 14, 2003). "The Hours". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "The Hours (2002) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Russo, Tom (March 15, 2009). "Chill with scenes of young vampires in love". The Boston Globe. p. 14.

- ^ "Laws of Attraction". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ "The Forgotten". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ "The Forgotten". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (September 30, 2005). "Countering Domestic Strife With Some Catchy Rhymes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ "Freedomland". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ "Children of Men". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ a b "Julianne Moore". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ Travers, Peter. "10 Best Movies of the Decade: Children of Men (2006)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Rooney, David (November 30, 2006). "The Vertical Hour". Variety. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Brantley, Ben (December 1, 2006). "Battle Zones in Hare Country". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ "The Vertical Hour". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "Next (2007)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Dargis, Manhola (April 27, 2007). "Next (2007)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Green, Sam (July 12, 2008). "I wasn't to blame for heiress murder, says art expert depicted on screen in 'incest threesome'". The Daily Mail. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Interview: Julianne Moore's challenging role in Savage Grace". The Mirror. July 10, 2008. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Savage Grace". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Savage Grace (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (July 11, 2008). "Savage Grace". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 21, 2007). "I'm Not There". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Blindness (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Blindness". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "A Single Man". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 11, 2010). "A Single Man". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (September 11, 2010). "A Single Man". Variety. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2009". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ Harp, Justin (December 28, 2012). "Julianne Moore returning to '30 Rock'". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "'30 Rock' finale recap: Tina Fey's Liz Lemon and the rest of the crew get appropriate last hurrah". Daily News. February 1, 2013. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ Robey, Tim (April 8, 2010). "Shelter, review". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Sinz, Cameron (February 19, 2013). "Watch: Trailer for Julianne Moore's Five Years in the Making '6 Souls' Lands With a Thud". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Fritz, Ben (July 12, 2010). "'The Kids Are All Right' opens well". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Freydkin, Donna (July 6, 2010). "Ruffalo, Moore get that family feeling in 'Kids Are All Right'". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ "The Kids Are All Right". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Kids Are All Right – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Sharkey, Betsy (July 8, 2010). "Movie review: 'The Kids Are All Right'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ "Interview with Julianne Moore". HBO. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Passafuime, Rocco (August 5, 2011). "Julianne Moore interview for Crazy, Stupid, Love". The Cinema Source. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Crazy, Stupid, Love". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ "Crazy, Stupid, Love. (2011)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ Rainey, James (March 6, 2012). "Julianne Moore gets inside Sarah Palin's skin for 'Game Change'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Dover, Sara (March 8, 2012). "'Game Change' Review: Critics Divided But Praise Julianne Moore". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ "Game Change (2012) (TV) – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ "Being Flynn (2012)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b "What Maisie Knew". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Hay, Carla (May 4, 2013). "Julianne Moore talks about playing a bad mother in 'What Maisie Knew'". Examiner. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Nigel M. (May 6, 2013). "Julianne Moore On Playing a Troubled Rock Star in 'What Maisie Knew' and Why Acting Doesn't Scare Her". Indie Wire. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ "Don Jon". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ Pols, Mary (September 26, 2013). "Don Jon: Love, Lust and Loneliness". Time. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ "The English Teacher". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b LaSalle, Mick (October 17, 2013). "'Carrie' review: less searing than the original". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Zwecker, Bill (October 17, 2013). "'Carrie': Pointless update of a horror classic". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Ginsberg, Merle (August 21, 2012). "Emmys 2012: Julianne Moore on Becoming Sarah Palin and Moving to TV Full Time". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Carrie (2013)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ "Carrie". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Non-Stop (2014)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ "Non-Stop (2014)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Chang, Justin (May 24, 2014). "Cannes: 'Winter Sleep' Wins Palme d'Or". Variety. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (May 22, 2014). "Julianne Moore on Maps to the Stars: 'The longer you live the Hollywood lifestyle, the more empty you become'". The Guardian. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (May 18, 2014). "Cannes Film Review: 'Maps to the Stars'". Variety. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Lodge, Guy. "'Winter Sleep' wins Palme d'Or at Cannes, Julianne Moore and Timothy Spall take acting prizes". Yahoo. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ "Julianne Moore". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ McNary, Dave (November 5, 2013). "AFM: Julianne Moore Boards Adaptation of 'Alice' Novel". Variety. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Nigel M. (December 12, 2014). "How Julianne Moore Pulled Off Her Devastating Performance in 'Still Alice'". Indiewire. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Thomson, David (December 3, 2014). "'Still Alice' Isn't the Year's Best Film But It May Be the Most Important". New Republic. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (December 4, 2014). "'Still Alice' powerfully presents a mind falling to Alzheimer's". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Young, Deborah (August 9, 2014). "'Still Alice': Toronto Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

Ehrlich, David (December 2, 2014). "Still Alice". Time Out. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

Lacey, Liam (January 23, 2014). "Julianne Moore masters Alzheimer's disappearing act in Still Alice". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved February 7, 2015. - ^ "Seventh Son – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Goldblatt, Daniel (September 13, 2013). "Julianne Moore Cast in 'The Hunger Games: Mockingjay'". Variety. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (February 13, 2014). "Julianne Moore, Zach Galifianakis Join Ellen Page in Gay Rights Drama 'Freeheld'". The Wrap. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ Fleming Jr, Mike (January 15, 2014). "Julianne Moore To Star With Greta Gerwig In Rebecca Miller-Helmed 'Maggie's Plan'". Deadline. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ^ Lipworth, Elaine (September 19, 2011). "Julianne Moore: marriage is really hard". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Otto, Jeff (April 29, 2004). "Interview: Julianne Moore". IGN. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Sgura, Giampaolo (August 16, 2013). "Exclusive Peek: Julianne Moore Opens Up on Fashion, Fame and Family in October InStyle". InStyle. Archived from the original on September 24, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Most Beautiful—Julianne Moore". People. May 8, 1995. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

Tauber, Michelle (May 12, 2003). "50 Most Beautiful People". People. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

"World's Most Beautiful People—Julianne Moore". People. April 30, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

"Most Beautiful 2013". People. April 18, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2014. - ^ a b c Brantley, Ben (March 9, 2003). "OSCAR FILMS: The Housewife and the Butcher; In the Art of Julianne Moore, Serenity Masks the Panic". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help) - ^ a b c Iley, Chrissy (July 6, 2008). "Red Alert". The Observer. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Freckleface Strawberry, Musical". Joseph Weinberger Ltd. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Moore, Julianne (2007). Freckleface Strawberry. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-59990-107-7.

- ^ Snook, Raven (August 18, 2012). "Freckleface Strawberry the Musical". Time Out. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Hammel, Sara (October 21, 2007). "Julianne Moore's Old Nickname: Freckleface Strawberry". People. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Freckleface Strawberry". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Ellis, Kori (March 22, 2013). "Julianne Moore dishes on motherhood and Freckleface Strawberry". Sheknows. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ Graeber, Laurel (October 19, 2010). "An Ugly Duckling Gets Her Ginger Up Over Fitting In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (July 20, 2010). "Julianne Moore's New Musical Is All Right for the Kids". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ Cericola, Rachel (March 18, 2013). "Julianne Moore on Work, Being a Mom, and Freckleface Strawberry". Wired. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Julianne Moore Recommends These Books for You". Redbook. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "My Mom Is a Foreigner, But Not to Me". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Random House Children's Books Acquires New Books From Julianne Moore Based on Her Bestselling 'Freckleface Strawberry' Character". Children's Book Council. November 21, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "Julianne Moore". Us Weekly. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Harp, Justin (October 2, 2012). "Beyoncé, Jennifer Lopez support Barack Obama in campaign video – watch". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ "Look Who's Helping Save the Children". Save the Children. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "Julianne Moore – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

External links

- Julianne Moore at IMDb

- Julianne Moore at AllMovie

- Julianne Moore collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Julianne Moore collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Julianne Moore on Twitter

- 1960 births

- 20th-century American actresses

- 20th-century British actresses

- 21st-century American actresses

- 21st-century American writers

- 21st-century British actresses

- 21st-century women writers

- Actresses from New York City

- Actresses from North Carolina

- American atheists

- American children's writers

- American film actresses

- American gun control advocates

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American soap opera actresses

- American stage actresses

- American pro-choice activists

- American television actresses

- American women writers

- Best Actress Academy Award winners

- Best Actress BAFTA Award winners

- Best Drama Actress Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Miniseries or Television Movie Actress Golden Globe winners

- Boston University College of Fine Arts alumni

- British people of Scottish descent

- British film actresses

- British soap opera actresses

- British stage actresses

- British television actresses

- Daytime Emmy Award winners

- Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Younger Actress in a Drama Series winners

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Female Lead winners

- LGBT rights activists from the United States

- Living people

- Military brats

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actress in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Miniseries or Television Movie Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- People from Fayetteville, North Carolina

- People from Greenwich Village

- Silver Bear for Best Actress winners

- Volpi Cup winners

- Writers from New York City

- Writers from North Carolina

- Women writers for children

- New York Democrats

- North Carolina Democrats