Placental abruption

| Placental abruption | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

Placental abruption (also known as abruptio placentae) is a complication of pregnancy, wherein the placental lining has separated from the uterus of the mother prior to delivery.[1] It is the most common pathological cause of late pregnancy bleeding. In humans, it refers to the abnormal separation after 20 weeks of gestation and prior to birth. It occurs on average in 0.5%, or 1 in 200, deliveries.[1] Placental abruption is a significant contributor to maternal mortality worldwide; early and skilled medical intervention is needed to ensure a good outcome, and this is not available in many parts of the world. Treatment depends on how serious the abruption is and how far along the woman is in her pregnancy.[2]

Placental abruption has effects on both mother and fetus. The effects on the mother depend primarily on the severity of the abruption, while the effects on the fetus depend on both its severity and the gestational age at which it occurs.[3] The heart rate of the fetus can be associated with the severity.[4]

Signs and symptoms

- in the early stages, there may be no symptoms[1]

- sudden-onset abdominal pain[1]

- contractions that don't stop (and may follow one another so rapidly as to seem continuous)[1]

- pain in the uterus[1]

- tenderness in the abdomen[1]

- vaginal bleeding[1]

- uterus may be disproportionately enlarged

- pallor

- nonreassuring fetal status, i.e. decreased fetal movement, worrisome fetal heart rate[1]

- signs and symptoms can vary[1]

Risk factors

- Pre-eclampsia [3]

- Chronic hypertension. [5]

- Maternal smoking is associated with up to 90% increased risk.[6]

- Maternal trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents, assaults, falls or nosocomial infection.

- Short umbilical cord

- Prolonged rupture of membranes (>24 hours).[7]

- Thrombophilia [3]

- Retroplacental fibromyoma

- Multiparity [3]

- Multiple pregnancy[3]

- Maternal age: pregnant women who are younger than 20 or older than 35 are at greater risk.

- History of placental abruption in a previous pregnancy.[8]

- History of a previous Caesarean section[3][9]

- some infections are also diagnosed as a cause

- cocaine intoxication[10]

- Cocaine abuse during pregnancy.[11]

Pathophysiology

Trauma, hypertension, or coagulopathy contributes to the avulsion of the anchoring placental villi from the expanding lower uterine segment, which in turn, leads to bleeding into the decidua basalis. This can push the placenta away from the uterus and cause further bleeding. Bleeding through the vagina, called overt or external bleeding, occurs 80% of the time, though sometimes the blood will pool behind the placenta, known as concealed or internal placental abruption.

Women may present with vaginal bleeding, abdominal or back pain, abnormal or premature contractions, fetal distress or death.

Diagnosis

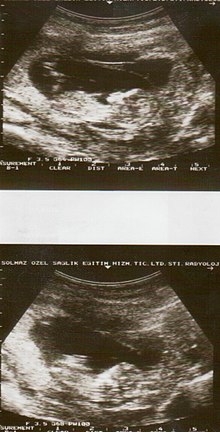

Placental abruption is suspected when a pregnant mother has sudden localized abdominal pain with or without bleeding. The fundus may be monitored because a rising fundus can indicate bleeding. An ultrasound may be used to rule out placenta praevia but is not diagnostic for abruption. The diagnosis is one of exclusion, meaning other possible sources of vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain have to be ruled out in order to diagnose placental abruption.[1] Of note, use of magnetic resonance imaging has been found to be highly sensitive in depicting placental abruption, and may be considered if no ultrasound evidence of placental abruption is present, especially if the diagnosis of placental abruption would change management.[12]

Classification

Based on severity:

- Class 0: asymptomatic. Diagnosis is made retrospectively by finding an organized blood clot or a depressed area on a delivered placenta.

- Class 1: mild and represents approximately 48% of all cases. Characteristics include the following:

- No vaginal bleeding to mild vaginal bleeding

- Slightly tender uterus

- Normal maternal BP and heart rate

- No coagulopathy

- No fetal distress

- Class 2: moderate and represents approximately 27% of all cases. Characteristics include the following:

- No vaginal bleeding to moderate vaginal bleeding

- Moderate-to-severe uterine tenderness with possible tetanic contractions

- Maternal tachycardia with orthostatic changes in BP and heart rate

- Fetal distress

- Hypofibrinogenemia (i.e., 50–250 mg/dL)

- Class 3: severe and represents approximately 24% of all cases. Characteristics include the following:

- No vaginal bleeding to heavy vaginal bleeding

- Very painful tetanic uterus

- Maternal shock

- Hypofibrinogenemia (i.e., <150 mg/dL)

- Coagulopathy

- Fetal death

Prevention

Although the risk of placental abruption cannot be eliminated, it can be reduced. Avoiding tobacco, alcohol and cocaine during pregnancy decreases the risk. Staying away from activities which have a high risk of physical trauma is also important. Women who have high blood pressure or who have had a previous placental abruption and want to conceive must be closely supervised by a doctor.[13]

The risk of placental abruption can be reduced by maintaining a good diet including taking folic acid, regular sleep patterns and correction of pregnancy-induced hypertension.

It is crucial for women to be made aware of the signs of placental abruption, such as vaginal bleeding, and that if they experience such symptoms they must get into contact with their health care provider/the hospital without any delay.

Management

Treatment depends on the amount of blood loss and the status of the fetus. If the fetus is less than 36 weeks and neither mother or fetus is in any distress, then they may simply be monitored in hospital until a change in condition or fetal maturity whichever comes first.

Immediate delivery of the fetus may be indicated if the fetus is mature or if the fetus or mother is in distress. Blood volume replacement to maintain blood pressure and blood plasma replacement to maintain fibrinogen levels may be needed. Vaginal birth is usually preferred over caesarean section unless there is fetal distress. Caesarean section is contraindicated in cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Patient should be monitored for 7 days for PPH. Excessive bleeding from uterus may necessitate hysterectomy. The mother may be given Rhogam if she is Rh negative.

Prognosis

The prognosis of this complication depends on whether treatment is received by the patient, on the quality of treatment, and on the severity of the abruption. Outcomes for the baby also depend on the gestational age.[1]

In the Western world, maternal deaths due to placental abruption are rare; for instance a study done in Finland found that, between 1972 and 2005 placental abruption had a maternal mortality rate of 0.4 per 1,000 cases (which means that 1 in 2,500 women who had placental abruption died); this was similar to other Western countries during that period.[14] The prognosis on the fetus is worse, currently, in the UK, about 15% of fetuses die following this event.[3]

Without any form of medical intervention, as often happens in many parts of the world, placental abruption has a high maternal mortality rate.

Mother

- A large loss of blood or hemorrhage may require blood transfusion(s).[15]

- If the mother's blood loss cannot be controlled, an emergency hysterectomy may become necessary.[15]

- The uterus may not contract properly after delivery so the mother may need medication to help her uterus contract.

- The mother may develop a blood clotting disorder, DIC.[15]

- A severe case of shock may affect other organs, such as the liver, kidney, and pituitary gland. Diffuse cortical necrosis in the kidney is a serious and often fatal complication.[15]

- Placental abruption by cause bleeding through the uterine muscle and into the mother's abdominal cavity, a condition called Couvelaire uterus.[16]

- Maternal death.[15]

Baby

- The baby may be born at a low birthweight.[15]

- Preterm delivery (prior to 37 weeks gestation).[15]

- The fetus may be deprived of oxygen and thus suffer from asphyxia.[15]

- Placental abruption may also result in fetal death, or stillbirth.[15]

- The newborn infant may have learning issues at later development stages, often requiring professional pedagogical aid.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sheffield, [edited by] F. Gary Cunningham, Kenneth J. Leveno, Steven L. Bloom, Catherine Y. Spong, Jodi S. Dashe, Barbara L. Hoffman, Brian M. Casey, Jeanne S. (2014). Williams obstetrics (24th edition. ed.). ISBN 978-0071798938.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Placental abruption | Pregnancy | Pregnancy complications | March of Dimes". marchofdimes.org. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Placenta and Placental Problems | Doctor". Patient.co.uk. 2011-03-18. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ Usui, Rie; Matsubara, Shigeki; Ohkuchi, Akihide; Kuwata, Tomoyuki; Watanabe, Takashi; Izumi, Akio; Suzuki, Mitsuaki (2007). "Fetal heart rate pattern reflecting the severity of placental abruption". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 277 (3): 249–53. doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0471-9. PMID 17896112.

- ^ Ananth, CV; Savitz, DA; Williams, MA (August 1996). "Placental abruption and its association with hypertension and prolonged rupture of membranes: a methodologic review and meta-analysis". Obstetrics and gynecology. 88 (2): 309–18. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(96)00088-9. PMID 8692522.

- ^ Ananth, C (1999). "Incidence of placental abruption in relation to cigarette smoking and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: A meta-analysis of observational studies". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 93 (4): 622. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00408-6.

- ^ Ananth, CV; Savitz, DA; Williams, MA (August 1996). "Placental abruption and its association with hypertension and prolonged rupture of membranes: a methodologic review and meta-analysis". Obstetrics and gynecology. 88 (2): 309–18. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(96)00088-9. PMID 8692522.

- ^ Ananth, CV; Savitz, DA; Williams, MA (August 1996). "Placental abruption and its association with hypertension and prolonged rupture of membranes: a methodologic review and meta-analysis". Obstetrics and gynecology. 88 (2): 309–18. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(96)00088-9. PMID 8692522.

- ^ Klar, M; Michels, KB (September 2014). "Cesarean section and placental disorders in subsequent pregnancies--a meta-analysis". Journal of perinatal medicine. 42 (5): 571–83. doi:10.1515/jpm-2013-0199. PMID 24566357.

- ^ Flowers, D; Clark, JF; Westney, LS (1991). "Cocaine intoxication associated with abruptio placentae". Journal of the National Medical Association. 83 (3): 230–2. PMC 2627035. PMID 2038082.

- ^ Cressman, AM; Natekar, A; Kim, E; Koren, G; Bozzo, P (July 2014). "Cocaine abuse during pregnancy". Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 36 (7): 628–31. PMID 25184982.

- ^ Masselli, G; Brunelli, R; Di Tola, M; Anceschi, M; Gualdi, G (April 2011). "MR imaging in the evaluation of placental abruption: correlation with sonographic findings". Radiology. 259 (1): 222–30. doi:10.1148/radiol.10101547. PMID 21330568.

- ^ "Placental abruption: Prevention". MayoClinic.com. 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ Tikkanen, Minna; Gissler, Mika; Metsäranta, Marjo; Luukkaala, Tiina; Hiilesmaa, Vilho; Andersson, Sture; Ylikorkala, Olavi; Paavonen, Jorma; Nuutila, Mika (2009). "Maternal deaths in Finland: Focus on placental abruption". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 88 (10): 1124–7. doi:10.1080/00016340903214940. PMID 19707898.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tikkanen, M (February 2011). "Placental abruption: epidemiology, risk factors and consequences". Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 90 (2): 140–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01030.x. PMID 21241259.

- ^ Pitaphrom, A; Sukcharoen, N (October 2006). "Pregnancy outcomes in placental abruption". Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 89 (10): 1572–8. PMID 17128829.

External links

- Emergency medicine: Abruptio Placentae, emedicine.com, April 5, 2005

- Obstetrics/Gynecology: Abruptio Placentae, emedicine.com, August 31, 2005

- Placental Abruption Awareness site: Click here for further information about Placental Abruption