Tonsillitis

| Tonsillitis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Family medicine, infectious diseases, otorhinolaryngology |

Tonsillitis (/ˌtɒnsɪˈlaɪtɪs/ TON-si-LEYE-tis) is inflammation of the tonsils most commonly caused by viral or bacterial infection. Symptoms may include sore throat and fever. When caused by a bacterium belonging to the group A streptococcus, it is typically referred to as strep throat. The overwhelming majority of people recover completely, with or without medication. In 40%, symptoms will resolve in three days, and within one week in 85% of people, regardless of whether streptococcal infection is present or not.[1]

Signs and symptoms

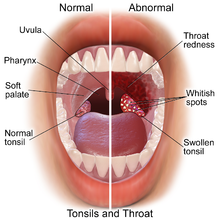

Common signs and symptoms include:[2][3][4][5]

- sore throat

- red, swollen tonsils

- pain when swallowing

- high temperature (fever)

- coughing

- headache

- tiredness

- chills

- a general sense of feeling unwell (malaise)

- white pus-filled spots on the tonsils

- swollen lymph nodes (glands) in the neck

- pain in the ears or neck

- weight loss

- difficulty ingesting and swallowing meal/liquid intake

- difficulty sleeping

Less common symptoms include:

- nausea

- fatigue

- stomach ache

- vomiting

- furry tongue

- bad breath (halitosis)

- voice changes

- difficulty opening the mouth (trismus)

- loss of appetite

- Anxiety/fear of choking

In cases of acute tonsillitis, the surface of the tonsil may be bright red and with visible white areas or streaks of pus.[6]

Tonsilloliths occur in up to 10% of the population frequently due to episodes of tonsillitis.[7]

Causes

The most common cause is viral infection and includes adenovirus, rhinovirus, influenza, coronavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus.[2][3][4][5] It can also be caused by Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, or HIV.[2][3][4][5] The second most common cause is bacterial infection of which the predominant is Group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS), which causes strep throat.[2][3][4][5] Less common bacterial causes include: Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA ),[8]Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, Fusobacterium sp., Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Treponema pallidum, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.[2][3][4][5]

Anaerobic bacteria have been implicated in tonsillitis and a possible role in the acute inflammatory process is supported by several clinical and scientific observations.[9]

Under normal circumstances, as viruses and bacteria enter the body through the nose and mouth, they are filtered in the tonsils.[10][11] Within the tonsils, white blood cells of the immune system destroy the viruses or bacteria by producing inflammatory cytokines like phospholipase A2,[12] which also lead to fever.[10][11] The infection may also be present in the throat and surrounding areas, causing inflammation of the pharynx.[13]

Sometimes, tonsillitis is caused by an infection of spirochaeta and treponema, in this case called Vincent's angina or Plaut-Vincent angina.[14]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of GABHS tonsillitis can be confirmed by culture of samples obtained by swabbing both tonsillar surfaces and the posterior pharyngeal wall and plating them on sheep blood agar medium. The isolation rate can be increased by incubating the cultures under anaerobic conditions and using selective growth media. A single throat culture has a sensitivity of 90%-95% for the detection of GABHS (which means that GABHS is actually present 5%-10% of the time culture suggests that it is absent). This small percentage of false-negative results are part of the characteristics of the tests used but are also possible if the patient has received antibiotics prior to testing. Identification requires 24 to 48 hours by culture but rapid screening tests (10–60 minutes), which have a sensitivity of 85-90%, are available. Older antigen tests detect the surface Lancefield group A carbohydrate. Newer tests identify GABHS serotypes using nucleic acid (DNA) probes or polymerase chain reaction. Bacterial culture may need to be performed in cases of a negative rapid streptococcal test.[15]

True infection with GABHS, rather than colonization, is defined arbitrarily as the presence of >10 colonies of GABHS per blood agar plate. However, this method is difficult to implement because of the overlap between carriers and infected patients. An increase in antistreptolysin O (ASO) streptococcal antibody titer 3–6 weeks following the acute infection can provide retrospective evidence of GABHS infection[16] and is considered definitive proof of GABHS infection.

Increased values of secreted phospholipase A2[12] and altered fatty acid metabolism[17] in patients with tonsillitis may have diagnostic utility.

Treatment

Treatments to reduce the discomfort from tonsillitis include:[2][3][4][5][13][18][19]

- pain relief, anti-inflammatory, fever reducing medications (paracetamol/acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen)

- sore throat relief (warm salt water gargle, lozenges, dissolved aspirin gargle (aspirin is an anti inflammatory, do not take any other anti inflammatory drugs with this method), and warm/hot liquids.

If the tonsillitis is caused by group A streptococcus, then antibiotics are useful, with penicillin or amoxicillin being primary choices.[20] Cephalosporins and macrolides are considered good alternatives to penicillin in the acute setting.[21] A macrolide such as erythromycin is used for people allergic to penicillin. Individuals who fail penicillin therapy may respond to treatment effective against beta-lactamase producing bacteria[22] such as clindamycin or amoxicillin-clavulanate. Aerobic and anaerobic beta lactamase producing bacteria that reside in the tonsillar tissues can "shield" group A streptococcus from penicillins.[23]

When tonsillitis is caused by a virus, the length of illness depends on which virus is involved. Usually, a complete recovery is made within one week; however, symptoms may last for up to two weeks. Chronic cases may be treated with tonsillectomy (surgical removal of tonsils) as a choice for treatment.[24] Of note, scientific research has found that children have had only a modest benefit from tonsillectomy for chronic cases of tonsillitis.[25]

Prognosis

Since the advent of penicillin in the 1940s, a major preoccupation in the treatment of streptococcal tonsillitis has been the prevention of rheumatic fever, and its major effects on the nervous system (Sydenham's chorea) and heart. Recent evidence would suggest that the rheumatogenic strains of group A beta hemolytic strep have become markedly less prevalent and are now only present in small pockets such as in Salt Lake City.[26] This brings into question the rationale for treating tonsillitis as a means of preventing rheumatic fever.

Complications may rarely include dehydration and kidney failure due to difficulty swallowing, blocked airways due to inflammation, and pharyngitis due to the spread of infection.[2][3][4][5][13]

An abscess may develop lateral to the tonsil during an infection, typically several days after the onset of tonsillitis. This is termed a peritonsillar abscess (or quinsy).

Rarely, the infection may spread beyond the tonsil resulting in inflammation and infection of the internal jugular vein giving rise to a spreading septicaemia infection (Lemierre's syndrome).

In chronic/recurrent cases (generally defined as seven episodes of tonsillitis in the preceding year, five episodes in each of the preceding two years or three episodes in each of the preceding three years),[27][28][29] or in acute cases where the palatine tonsils become so swollen that swallowing is impaired, a tonsillectomy can be performed to remove the tonsils. Patients whose tonsils have been removed are still protected from infection by the rest of their immune system.

In strep throat, very rarely diseases like rheumatic fever[30] or glomerulonephritis[31] can occur. These complications are extremely rare in developed nations but remain a significant problem in poorer nations.[32][33] Tonsillitis associated with strep throat, if untreated, is hypothesized to lead to pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS).[34]

References

- ^ Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP, Spinks AB (October 2006). Del Mar, Chris B (ed.). "Antibiotics for sore throat". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 18, (4) (4): CD000023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub3. PMID 17054126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Tonsillopharyngitis at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ a b c d e f g Wetmore RF. (2007). "Tonsils and adenoids". In Bonita F. Stanton; Kliegman, Robert; Nelson, Waldo E.; Behrman, Richard E.; Jenson, Hal B. (ed.). Nelson textbook of pediatrics. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2450-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Thuma P. (2001). "Pharyngitis and tonsillitis". In Hoekelman, Robert A. (ed.). Primary pediatric care. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0-323-00831-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Simon HB (2005). "Bacterial infections of the upper respiratory tract". In Dale, David (ed.). ACP Medicine, 2006 Edition (Two Volume Set) (Webmd Acp Medicine). WebMD Professional Publishing. ISBN 0-9748327-6-6.

- ^ Tonsillitis and Adenoid Infection MedicineNet. Retrieved on 2010-01-25

- ^ S. G. Nour; Mafee, Mahmood F.; Valvassori, Galdino E.; Galdino E. Valbasson; Minerva Becker (2005). Imaging of the head and neck. Stuttgart: Thieme. p. 716. ISBN 1-58890-009-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brook, I.; Foote, P. A. (2006). "Isolation of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus from the surface and core of tonsils in children". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 70 (12): 2099–2102. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.08.004. PMID 16962178.

- ^ Brook, I. (2005). "The role of anaerobic bacteria in tonsillitis". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 69 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.08.007. PMID 15627441.

- ^ a b van Kempen MJ, Rijkers GT, Van Cauwenberge PB (May 2000). "The immune response in adenoids and tonsils". Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 122 (1): 8–19. doi:10.1159/000024354. PMID 10859465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Perry M, Whyte A (September 1998). "Immunology of the tonsils". Immunology Today. 19 (9): 414–21. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(98)01307-3. PMID 9745205.

- ^ a b Ezzeddini R, Darabi M, Ghasemi B, Jabbari Moghaddam Y, Jabbari Y, Abdollahi S, et al. (2012). "Circulating phospholipase-A2 activity in obstructive sleep apnea and recurrent tonsillitis". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 76 (4): 471–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.12.026. PMID 22297210.

- ^ a b c MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Tonsillitis

- ^ Van Cauwenberge P (1976). "[Significance of the fusospirillum complex (Plaut-Vincent angina)]". Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg (in Dutch and Flemish). 30 (3): 334–45. PMID 1015288. — fusospirillum complex (Plaut-Vincent angina) Van Cauwenberge studied the tonsils of 126 patients using direct microscope observation. The results showed that 40% of acute tonsillitis was caused by Vincent's angina and 27% of chronic tonsillitis was caused by Spirochaeta

- ^ Leung AK, Newman R, Kumar A, Davies HD (2006). "Rapid antigen detection testing in diagnosing group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis". Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 6 (5): 761–6. doi:10.1586/14737159.6.5.761. PMID 17009909.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brook I (2007). "Overcoming penicillin failures in the treatment of Group A streptococcal pharyngo-tonsillitis". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 71 (10): 1501–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.06.006. PMID 17644191.

- ^ Ezzedini R, Darabi M, Ghasemi B, Darabi M, Fayezi S, Moghaddam YJ, et al. (2013). "Tissue fatty acid composition in obstructive sleep apnea and recurrent tonsillitis". Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 77 (6): 1008–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.03.033. PMID 23643333.

- ^ Boureau, F.; Pelen, F; Verriere, F; Paliwoda, A; Manfredi, R; Farhan, M; Wall, R; et al. (1999). "Evaluation of Ibuprofen vs Paracetamol Analgesic Activity Using a Sore Throat Pain Model". Clinical Drug Investigation. 17: 1–8. doi:10.2165/00044011-199917010-00001.

- ^ Praskash, T.; et al. (2001). "Koflet lozenges in the Treatment of Sore Throat". The Antiseptic. 98: 124–7.

- ^ Touw-Otten FW, Johansen KS (1992). "Diagnosis, antibiotic treatment and outcome of acute tonsillitis: report of a WHO Regional Office for Europe study in 17 European countries". Fam Pract. 9 (3): 255–62. doi:10.1093/fampra/9.3.255. PMID 1459378.

- ^ Casey JR, Pichichero ME (2004). "Meta-analysis of cephalosporin versus penicillin treatment of group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis in children". Pediatrics. 113 (4): 866–882. doi:10.1542/peds.113.4.866. PMID 15060239.

- ^ Brook I (2009). "The role of beta-lactamase-producing-bacteria in mixed infections". BMC Infect Dis. 9: 202. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-9-202. PMC 2804585. PMID 20003454.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Brook I (2007). "Microbiology and principles of antimicrobial therapy for head and neck infections". Infect Dis Clin North Am. 21 (2): 355–91. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.014. PMID 17561074.

- ^ Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. (1984). "Efficacy of tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection in severely affected children. Results of parallel randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials". N. Engl. J. Med. 310 (11): 674–83. doi:10.1056/NEJM198403153101102. PMID 6700642.

- ^ Burton, MJ; Glasziou, PP; Chong, LY; Venekamp, RP (19 November 2014). "Tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy versus non-surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 11: CD001802. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001802.pub3. PMID 25407135.

- ^ Shulman ST, Stollerman G, Beall B, Dale JB, Tanz RR (Feb 15, 2006). "Temporal changes in streptococcal M protein types and the near-disappearance of acute rheumatic fever in the United States". Clin Infect Dis. 42 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1086/499812. PMID 16421785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. (January 1999). "6.3 Referral Criteria for Tonsillectomy". Management of Sore Throat and Indications for Tonsillectomy. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. ISBN 1-899893-66-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=and|publisher=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) — notes though that these criteria "have been arrived at arbitrarily" from:

Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. (1984). "Efficacy of tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection in severely affected children. Results of parallel randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials". N. Engl. J. Med. 310 (11): 674–83. doi:10.1056/NEJM198403153101102. PMID 6700642. - ^ Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Colborn DK, Bernard BS, Rockette HE, Kurs-Lasky M (2002). "Tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection in moderately affected children". Pediatrics. 110 (1 Pt 1): 7–15. doi:10.1542/peds.110.1.7. PMID 12093941.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) — this later study by the same team looked at less severely affected children and concluded "modest benefit conferred by tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy in children moderately affected with recurrent throat infection seems not to justify the inherent risks, morbidity, and cost of the operations" - ^ Wolfensberger M, Mund MT (2004). "[Evidence based indications for tonsillectomy]". Ther Umsch (in German). 61 (5): 325–8. doi:10.1024/0040-5930.61.5.325. PMID 15195718. — review of literature of the past 25 years concludes "No consensus has yet been reached, however, about the number of annual episodes that justify tonsillectomy"

- ^ Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP, Spinks AB (2004). Del Mar, Chris (ed.). "Antibiotics for sore throat". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub2. PMID 15106140.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) — Meta-analysis of published research - ^ Zoch-Zwierz W, Wasilewska A, Biernacka A, et al. (2001). "[The course of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis depending on methods of treatment for the preceding respiratory tract infection]". Wiad. Lek. (in Polish). 54 (1–2): 56–63. PMID 11344703.

- ^ Ohlsson, A.; Clark, K (September 28, 2004). "Antibiotics for sore throat to prevent rheumatic fever: Yes or No? How the Cochrane Library can help". CMAJ. 171 (7): 721–3. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1041275. PMC 517851. PMID 15451830. — Canadian Medical Association Journal commentary on Cochrane analysis

- ^ Danchin, MH; Curtis, N; Nolan, TM; Carapetis, JR (2002). "Treatment of sore throat in light of the Cochrane verdict: is the jury still out?". MJA. 177 (9): 512–5. PMID 12405896. — Medical Journal of Australia commentary on Cochrane analysis

- ^ Pickering, Larry K., ed. (2006). "Group A streptococcal infections". Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases). Amer Academy of Pediatrics. ISBN 1-58110-194-5.