Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic

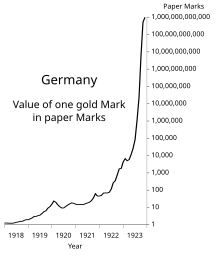

The hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic was a three-year period of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic (modern-day Germany) between June 1921 and January 1924. The hyperinflation was a cause of considerable internal political instability in the country, the occupation of the Ruhr by foreign troops and misery for the general populace.

History

Background

In order to pay for the large costs of the First World War, Germany suspended the gold standard (i.e., the convertibility of its currency into gold) when the war broke out. Unlike the French Third Republic, which imposed its first income tax to pay for the war, the German Emperor Wilhelm II and the German parliament (the Reichstag) decided without opposition to fund the war entirely by borrowing,[1] a decision criticized by financial experts such as Hjalmar Schacht as a dangerous risk for currency devaluation.[2] The government apparently believed that it would be able to pay off the debt by annexing resource-rich industrial territory to the west and east and imposing massive reparations on the defeated Allies.[3] The result was that the exchange rate of the mark against the United States dollar steadily devalued throughout the war from 4.2 to 7.9 marks per dollar.[4]

The government's strategy backfired when Germany lost the war. The new Weimar Republic was now saddled with a massive war debt that it could not afford, made even worse by the fact that it was printing money without the economic resources to back it up.[3] The Treaty of Versailles further accelerated the decline in the value of the mark, such that 48 paper marks were required to buy one US dollar by late 1919.[5]

German currency was relatively stable at about 90 marks per US dollar during the first half of 1921.[6] Because the western theatre of warfare during World War I was mostly in France and Belgium, Germany came out of the war with most of its industrial infrastructure intact and in a better position to become the dominant economic force on the European continent.[7] The London Ultimatum of May 1921, however, demanded reparations in gold or foreign currency to be paid in annual installments of 2,000,000,000 (2 billion) gold marks plus 26 percent of the value of Germany's exports.[8]

The first payment was made when it came due in June 1921.[9] It marked the beginning of an increasingly rapid devaluation of the mark, which fell in value to less than one third of a cent by November 1921 (approximately 330 Marks per US Dollar).[5] The total reparations demanded were 132,000,000,000 (132 billion) gold marks, of which Germany only had to pay 50 billion marks.[10]

Because reparations were required to be repaid in hard currency and not the rapidly depreciating paper mark, one strategy Germany employed was the mass printing of bank notes to buy foreign currency, which was in turn used to pay reparations. This greatly exacerbated the inflation rates of the paper mark.[11][12]

Hyperinflation

Beginning in August 1921, Germany began to buy foreign currency with marks at any price, but that only increased the speed of breakdown in the value of the mark.[13] The lower the mark sank in international markets, the greater the amount of marks was required to buy the foreign currency demanded by the Reparations Commission.[12]

During the first half of 1922, the mark stabilized at about 320 Marks per dollar.[5] At this time international reparations conferences were held, including one in June 1922 that was organized by US investment banker J. P. Morgan, Jr.[14] When these meetings produced no workable solution, the inflation changed to hyperinflation and the mark fell to 7,400 Marks per Dollar by December 1922.[5] The cost-of-living index was 41 in June 1922 and 685 in December, a 15-fold increase.

By the fall of 1922, Germany found itself unable to make reparations payments, since the price of gold was now well beyond what it could afford.[15] Also by this time, the mark was practically worthless, making it impossible for Germany to buy foreign exchange or gold using paper marks. Instead, reparations were to be paid in goods such as coal. In January 1923 French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr, the industrial region of Germany in the Ruhr valley, to ensure this. Inflation was exacerbated when workers in the Ruhr went on a general strike and the German government printed more money in order to continue paying them for their "passive resistance."[16] By November 1923, the American dollar was worth 4,210,500,000,000 German marks.[17]

-

50 000 Mark, Aachen, 1923

-

500 000 Mark, Leipzig, 1923

-

5 000 000 Mark, Danzig, 1923

-

50 000 000 Mark, Trier, 1923

-

500 000 000 Mark, Dresden, 1923

-

5 000 000 000 Mark, Berlin, 1923

-

50 000 000 000 Mark, Plauen, 1923

-

500 000 000 000 Mark, Berlin, 1923

-

5 000 000 000 000 Mark, Stuttgart, 1923

-

50 000 000 000 000 Eschweiler u. Stolberg 1923

Stabilization

The hyperinflation crisis naturally led prominent economists and politicians to seek a means to stabilize German currency. In August 1923, the economist Karl Helfferich proposed a plan to issue a new currency, the "Roggenmark" ("rye mark"), which was to be backed by mortgage bonds indexed to the market price of rye grain. His plan was rejected because of the greatly fluctuating price of rye in paper marks.

It was the Agriculture Minister Hans Luther who proposed a plan that substituted gold for rye and led to the issuance of the Rentenmark ("mortgage mark") backed by bonds indexed to the market price of gold.[18] The gold bonds were defined at the rate of 2790 gold marks per kilogram of gold, which was the same definition as the pre-war gold marks. The Rentenmarks were not redeemable in gold, but were only indexed to the gold bonds. The Rentenmark plan was adopted in monetary reform decrees on October 13–15, 1923, that set up a new bank, the Rentenbank, controlled by Hans Luther, who by then had become the new German Finance Minister.

After November 12, 1923, when Hjalmar Schacht became currency commissioner, Germany's central bank (the Reichsbank) was not allowed to discount any further government Treasury bills, which meant the corresponding issue of paper marks also ceased.[19] Discounting of commercial trade bills was allowed and the amount of Rentenmarks expanded, but the issue was strictly controlled to conform to current commercial and government transactions. The new Rentenbank refused credit to the government and to speculators who were not able to borrow Rentenmarks, because Rentenmarks were not legal tender.[20]

On November 16, 1923, when the new Rentenmark was introduced to replace the worthless paper marks issued by the Reichsbank. Twelve zeros were cut from prices, and the prices quoted in the new currency remained stable.

When Reichsbank president Rudolf Havenstein died on November 20, 1923, Schacht was appointed president of the Reichsbank. By November 30, 1923, there were 500 million Rentenmarks in circulation, which increased to 1 billion by January 1, 1924, and again to 1.8 billion Rentenmarks by July 1924. Meanwhile, the old paper Marks continued in circulation. The total paper marks increased to 1.2 sextillion (or 1,200,000,000,000,000,000,000) in July 1924 and continued to fall in value to one third of their conversion value in Rentenmarks.[20]

The monetary law of August 30, 1924, permitted exchange of each old paper 1 trillion mark note for one new Reichsmark, equivalent in value to one Rentenmark.

Revaluation

Eventually, some debts were reinstated to compensate creditors partially for the catastrophic reduction in value of debts originally quoted in paper marks before the hyperinflation took hold. A decree of 1925 reinstated some mortgages at 25% of face value in the new currency (effectively 25,000,000,000 times their value in the old paper marks) if they had been held 5 years or more. Similarly, some government bonds were reinstated at 2-1/2% of face value - to be paid after reparations were paid.[21] Mortgage debt was reinstated at much higher percentages than government bonds. Reinstatement of some debts, combined with a resumption of effective taxation in a still-devastated economy, triggered a wave of corporate bankruptcies.

One of the important issues of the stabilization of a hyperinflation is the revaluation. In its customary sense, this term refers to the raising of the exchange rate of one national currency against other currencies. It also means revalorization – the restoration of the value of a currency depreciated by inflation. The German government had the choice either by means of a revaluation law to finish the hyperinflation quickly or to allow sprawling and the political and violent disturbances on the streets. The German government argued in detail that the interests of creditors and debtors had to be fair and balanced. Neither the living standard price index nor the share price index were judged as relevant. The calculation of the conversion relation was considerably judged to the dollar index as well as to the wholesale price index. In principle, the German government followed the line of market-oriented reasoning that the dollar index and the wholesale price index would roughly indicate the true price level in general over the period of high inflation and hyperinflation. In addition, the revaluation was bound on the exchange rate mark and United States dollar to obtain the value of the Goldmark.[22]

The Law on the Revaluation of Mortgages and other Claims of 16 July 1925 (Gesetz über die Aufwertung von Hypotheken und anderen Ansprüchen or Aufwertungsgesetze, a.k.a. the Revaluation Act 1925) finally included only the relation of paper mark to gold mark for the period from January 1, 1918, to November 30, 1923, and the following days.[23] This led to the abandonment of the principle A mark is worth a mark recognized until then (the nominal value principle), because of the galloping inflation.[24] This law was challenged in the Supreme Court of the German Reich (Reichsgericht). The 5th Senate of the German Supreme Court (Reichsgericht) ruled on November 4, 1925, that the Revaluation Act 1925 was constitutional, even when weighed against the "Bill of Rights and Duties of Germans" (articles 109, 134, 152, and 153 of the Constitution).[25][26][27] This case was precedent-setting for the issue of judicial review in German jurisprudence.[28]

Analysis

The hyperinflation episode in the Weimar Republic in the early 1920s, although not the first or most severe instance of inflation in history (the Hungarian pengő and Zimbabwean dollar, for example, have been even more inflated), has been the subject of the most scholarly economic analysis and debate. The Weimar hyperinflation drew significant interest, as many of the dramatic and unusual economic behaviors now associated with hyperinflation were first documented systematically: order-of-magnitude increases in prices and interest rates, redenomination of the currency, consumer flight from cash to hard assets, and the rapid expansion of industries that produced those assets. German monetary economics was at that time heavily influenced by Chartalism and the German Historical School, and this conditioned the way the hyperinflation was analyzed.[29]

John Maynard Keynes described the situation in The Economic Consequences of the Peace: "The inflationism of the currency systems of Europe has proceeded to extraordinary lengths. The various belligerent Governments, unable, or too timid or too short-sighted to secure from loans or taxes the resources they required, have printed notes for the balance."

It was during this period of hyperinflation that French and British economic experts began to claim that Germany destroyed its economy with the purpose of avoiding reparations, but both governments had conflicting views on how to handle the situation. The French declared that Germany should keep paying reparations, while Britain sought to grant a moratorium that would allow for its financial reconstruction.[7]

Reparations accounted for about one third of the German deficit from 1920 to 1923,[30] and were therefore cited by the German government as one of the main causes of hyperinflation. Other causes cited included bankers and speculators (particularly foreign). The inflation reached its peak by November 1923,[31] but ended when a new currency (the Rentenmark) was introduced. In order to make way for the new currency, banks "turned the marks over to junk dealers by the ton"[32] to be recycled as paper.

Outcome

Later German monetary policy showed far greater concern for maintaining a sound currency, a concern that even affected Germany's attitude in resolving the European sovereign debt crisis from 2009 onwards.[33]

The hyperinflated, worthless marks became widely collected abroad. The Los Angeles Times estimated in 1924 that more of the decommissioned notes were spread about the United States than existed in Germany.[32]

The cause of the immense acceleration of prices that occurred during the German hyperinflation of 1922–23 seemed unclear and unpredictable to those who lived through it, but in retrospect was relatively simple. The Treaty of Versailles imposed a huge debt on Germany that could be paid only in gold or foreign currency. With its gold depleted, the German government attempted to buy foreign currency with German currency,[13] an action equivalent to selling German currency in exchange for payment in foreign currency, but the resulting increase in the supply of German marks on the market caused the German mark to fall rapidly in value, which greatly increased the number of marks needed to buy more foreign currency. This caused German prices of goods to rise rapidly, increasing the cost of operating the German government, which could not be financed by raising taxes because those taxes would be payable in the ever-less-valuable German currency. The alternative was some combination of running a budget deficit and simply creating more money, each of which increased the supply of German currency on the market and reduced that currency's price. When the German people realized that their money was rapidly losing value, they tried to spend it quickly. This increase in monetary velocity caused still more rapid increase in prices, creating a vicious cycle.[34] This placed the government and banks between two unacceptable alternatives: if they stopped the inflation this would cause immediate bankruptcies, unemployment, strikes, hunger, violence, collapse of civil order, insurrection, and revolution.[35] If they continued the inflation they would default on their foreign debt. The attempts to avoid both unemployment and insolvency ultimately failed when Germany had both.[35]

See also

Notes

- ^ Fergusson, When Money Dies; p. 10

- ^ Fergusson; When Money Dies; p. 11

- ^ a b Evans, p. 103.

- ^ Officer, Lawrence. "Exchange Rates Between the United States Dollar and Forty-one Currencies". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ a b c d Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (1943). Banking and Monetary Statistics 1914-1941 (PDF). Washington, DC. p. 671.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Laursen and Pedersen, page 134

- ^ a b Marks, page 53

- ^ Kolb, Eberhard (2012). The Weimar Republic. Translated by P.S. Falla (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 0-415-09077-6.

- ^ Fergusson, page 38.

- ^ Marks (1978), p. 237

- ^ Fergusson, page 36

- ^ a b Shapiro, page 187

- ^ a b Fergusson; When Money Dies; p. 40

- ^ Balderston, page 21

- ^ Evans, p. 104.

- ^ Civilization in the West, Seventh Edition, Kishlansky, Geary, and O'Brien, New York, page 807.

- ^ Coffin; "Western Civilizations"; p. 918

- ^ The Rentenmark Miracle, Gustavo H.B. Franco, page 16

- ^ Guttmann, pages 208-211

- ^ a b Fergusson, Chapter 13

- ^ Fergusson, Chapter 14

- ^ Fischer 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Fischer 2010, p. 84.

- ^ Fischer 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Friedrich 1928, p. 197.

- ^ RGZ III, 325

- ^ Fischer 2010, p. 89.

- ^ Friedrich 1928, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Monetary Explanations of the Weimar Republic's Hyperinflation: Some Neglected Contributions in Contemporary German Literature, David E.W. Laidler & George W. Stadler, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 30, pages 816, 818

- ^ The Economics of Inflation, Costantino Bresciani-Turroni, page 93

- ^ Fischer 2010, p. 64.

- ^ a b Americans With Marks Out of Luck, Cable and Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, 15 Nov 1924

- ^ Greece bailout: What's the future of the euro?, Ben Quinn, Christian Science Monitor, 28 March 2010

- ^ Parsson; Dying of Money; p. 116–117

- ^ a b Fergusson; When Money Dies; p. 254

References

- Balderston, prepared for the Economic History Society by Theo (2002). Economics and politics in the Weimar Republic (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-77760-7.

- Costantino Bresciani-Turroni, The Economics of Inflation (English transl.), Northampton, England: Augustus Kelly Publishers, 1937, on the German 1919-1923 inflation. [1]

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0141009759.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Feldman, Gerald D. (1996). The great disorder politics, economics, and society in the German inflation, 1914 - 1924 ([Nachdruck] ed.). New York, NY [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-510114-6.

- Fergusson, Adam (2010). When money dies : the nightmare of deficit spending, devaluation, and hyperinflation in Weimar Germany (1st [U.S.] ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-994-1.

- Fischer, Wolfgang Chr., ed. (2010). German Hyperinflation 1922/23: A Law and Economics Approach. Eul-Verlag Köln. ISBN 978-3-89936-931-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friedrich, Carl Joachim (June 1928). "The Issue of Judicial Review in Germany". Political Science Quarterly. 43 (2). JSTOR 2143300.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - When Money Buys Little - Jerry Jensen Study of the 1923 German postage stamps

- Karsten Laursen and Jorgen Pedersen, The German Inflation, North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam, 1964.

- Marks, Sally (September 1978). "The Myths of Reparations". Central European History. 11 (3). Cambridge University Press: 231–255. doi:10.1017/s0008938900018707. JSTOR 4545835.

- Marks, Sally (2003). The Illusion of Peace. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parsson, Jens O. (1974). Dying of Money : Lessons of the Great German and American Inflations. Boston: Wellspring Press.

- Shapiro, Max (1980). The penniless billionaires. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-0923-2.

- Widdig, Bernd (2001). Culture and inflation in Weimar Germany ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22290-3.