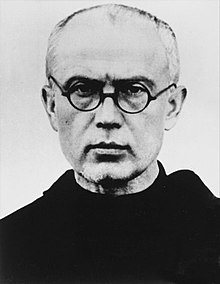

Maximilian Kolbe

Apostle of Consecration to Mary | |

| Religious, priest and martyr | |

| Born | 8 January 1894 Zduńska Wola, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 14 August 1941 (aged 47) Auschwitz concentration camp, Nazi Germany |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Lutheran Church, Anglican Church |

| Beatified | 17 October 1971, St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City[1] by Pope Paul VI |

| Canonized | 10 October 1982, St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City by Pope John Paul II |

| Major shrine | Basilica of the Immaculate Mediatrix of Grace, Niepokalanów, Teresin, Masovian Voivodeship, Poland |

| Feast | 14 August |

| Attributes | Prison uniform, needle being injected into an arm |

| Patronage | Against drug addictions, drug addicts, families, imprisoned people, journalists, political prisoners, prisoners, pro-life movement, amateur radio, esperantists.[2] |

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Maximilian Maria Kolbe, O.F.M. Conv. (Polish: Maksymilian Maria Kolbe [maksɨˌmʲilʲjan ˌmarʲja ˈkɔlbɛ]; 8 January 1894 – 14 August 1941) was a Polish Conventual Franciscan friar, who volunteered to die in place of a stranger in the German death camp of Auschwitz, located in German-occupied Poland during World War II. He was active in promoting the veneration of the Immaculate Virgin Mary, founding and supervising the monastery of Niepokalanów near Warsaw, operating a radio station, and founding or running several other organizations and publications.

Kolbe was canonized on 10 October 1982 by Pope John Paul II, and declared a Martyr of charity. He is the patron saint of drug addicts, political prisoners, families, journalists, prisoners, and the pro-life movement.[2] John Paul II declared him "The Patron Saint of Our Difficult Century".[3]

Due to Kolbe's efforts to promote consecration and entrustment to Mary, he is known as the Apostle of Consecration to Mary.[4]

Biography

Childhood

Maximilian Kolbe was born on 8 January 1894 in Zduńska Wola, in the Kingdom of Poland, which was a part of the Russian Empire, the second son of weaver Julius Kolbe and midwife Maria Dąbrowska.[5] His father was an ethnic German[6] and his mother was Polish. He had four brothers. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Pabianice.[5]

Kolbe's life was strongly influenced in 1906 by a childhood vision of the Virgin Mary.[2] He later described this incident:

That night I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.[7]

Franciscan friar

In 1907, Kolbe and his elder brother Francis joined the Conventual Franciscans.[8] They enrolled at the Conventual Franciscan minor seminary in Lwow later that year. In 1910, Kolbe was allowed to enter the novitiate, where he was given the religious name Maximilian. He professed his first vows in 1911, and final vows in 1914,[2] adopting the additional name of Maria (Mary).[5]

Kolbe was sent to Rome in 1912, where he attended the Pontifical Gregorian University. He earned a doctorate in philosophy in 1915 there. From 1915 he continued his studies at the Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure where he earned a doctorate in theology in 1919[5] or 1922[2] (sources vary). He was active in the consecration and entrustment to Mary. During his time as a student, he witnessed vehement demonstrations against Popes St. Pius X and Benedict XV in Rome during an anniversary celebration by the Freemasons. According to Kolbe,

They placed the black standard of the "Giordano Brunisti" under the windows of the Vatican. On this standard the archangel, St. Michael, was depicted lying under the feet of the triumphant Lucifer. At the same time, countless pamphlets were distributed to the people in which the Holy Father (i.e., the Pope) was attacked shamefully.[1][9]

Soon afterward, Kolbe organized the Militia Immaculata (Army of the Immaculate One), to work for conversion of sinners and enemies of the Catholic Church, specifically the Freemasons, through the intercession of the Virgin Mary.[2] So serious was Kolbe about this goal that he added to the Miraculous Medal prayer:

O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee. And for all those who do not have recourse to thee; especially the Masons and all those recommended to thee.[10]

In 1918, Kolbe was ordained a priest.[11] In July 1919 he returned to the newly independent Poland, where he was active in promoting the veneration of the Immaculate Virgin Mary.[5] He was strongly opposed to leftist – in particular, communist – movements.[5] From 1919 to 1922 he taught at the Kraków seminary.[2][5] Around that time, as well as earlier in Rome, he suffered from tuberculosis, which forced him to take a lengthy leave of absence from his teaching duties.[2][11] In January 1922 he founded the monthly periodical Rycerz Niepokalanej (Knight of the Immaculate), a devotional publication based on French Le Messager du Coeur de Jesus (Messenger of the Heart of Jesus).[5] From 1922 to 1926 he operated a religious publishing press in Grodno.[5] As his activities grew in scope, in 1927 he founded a new Conventual Franciscan monastery at Niepokalanów near Warsaw, which became a major religious publishing center.[2][5][11] A junior seminary was opened there two years later.[2]

Between 1930 and 1936, Kolbe undertook a series of missions to East Asia.[5] At first, he arrived in Shanghai, China, but failed to gather a following there.[5] Next, he moved to Japan, where by 1931 he founded a monastery at the outskirts of Nagasaki (it later gained a novitiate and a seminary) and started publishing a Japanese edition of the Knight of the Immaculate (Seibo no Kishi).[2][5][11] The monastery he founded remains prominent in the Roman Catholic Church in Japan.[2] Kolbe built the monastery on a mountainside that, according to Shinto beliefs, was not the side best suited to be in harmony with nature. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, Kolbe's monastery was saved because the other side of the mountain took the main force of the blast.[12] In mid-1932 he left Japan for Malabar, India, where he founded another monastery; this one however closed after a while.[2] Meanwhile, the monastery at Niepokalanów began in his absence to publish the daily newspaper, Mały Dziennik (The Little Daily), in alliance with the political group, the National Radical Camp (Obóz Narodowo Radykalny).[2][5] This publication reached a circulation of 137,000, and nearly double that, 225,000, on weekends.[13]

Poor health forced Kolbe to return to Poland in 1936.[2] Two years later, in 1938, he started a radio station at Niepokalanów, the Radio Niepokalanów.[2][14] He held an amateur radio licence, with the call sign SP3RN.[15]

Death at Auschwitz

After the outbreak of World War II, which started with the invasion of Poland by Germany, Fr. Maximilian Kolbe was one of the few brothers who remained in the monastery, where he organized a temporary hospital.[5] After the town was captured by the Germans, he was briefly arrested by them on 19 September 1939 but released on 8 December.[2][5] He refused to sign the Deutsche Volksliste, which would have given him rights similar to those of German citizens in exchange for recognizing his German ancestry.[16] Upon his release he continued work at his monastery, where he and other monks provided shelter to refugees from Greater Poland, including 2,000 Jews whom he hid from German persecution in their friary in Niepokalanów.[2][11][12][16][17][18] Kolbe also received permission to continue publishing religious works, though significantly reduced in scope.[16] The monastery thus continued to act as a publishing house, issuing a number of anti-Nazi German publications.[2][11] On 17 February 1941, the monastery was shut down by the German authorities.[2] That day Kolbe and four others were arrested by the German Gestapo and imprisoned in the Pawiak prison.[2] On 28 May, he was transferred to Auschwitz as prisoner #16670.[19]

Continuing to act as a priest, Kolbe was subjected to violent harassment, including beating and lashings, and once had to be smuggled to a prison hospital by friendly inmates.[2][16] At the end of July 1941, three prisoners disappeared from the camp, prompting SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Fritzsch, the deputy camp commander, to pick 10 men to be starved to death in an underground bunker to deter further escape attempts. When one of the selected men, Franciszek Gajowniczek, cried out, "My wife! My children!", Kolbe volunteered to take his place.[8]

According to an eye witness, an assistant janitor at that time, in his prison cell, Kolbe led the prisoners in prayer to Our Lady. Each time the guards checked on him, he was standing or kneeling in the middle of the cell and looking calmly at those who entered. After two weeks of dehydration and starvation, only Kolbe remained alive. “The guards wanted the bunker emptied, so they and a fellow prisoner, Brono Borgowiec[20] (who survived Auschwitz) gave Kolbe a lethal injection of carbolic acid. Kolbe is said to have raised his left arm and calmly waited for the deadly injection.[11] His remains were cremated on 15 August, the feast day of the Assumption of Mary.[16]

Canonization

On 12 May 1955, Kolbe was recognized as a Servant of God.[16] Kolbe was declared venerable by Pope Paul VI on 30 January 1969, beatified as a Confessor of the Faith by the same Pope in 1971 and canonized as a saint by Pope John Paul II on 10 October 1982.[2][21] Upon canonization, the Pope declared St. Maximilian Kolbe not a confessor, but a martyr.[2] The miracle which was used to confirm his beatification was the July 1918 cure of intestinal tuberculosis in Angela Testoni, and in August 1920, the cure of calcification of the arteries/sclerosis of Francis Ranier was attributed to Kolbe's intercession.[2]

After his canonization, St. Maximilian Kolbe's feast day was added to the General Roman Calendar. He is one of ten 20th-century martyrs who are depicted in statues above the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey, London.[22]

Controversies

Kolbe's recognition as a Christian martyr also created some controversy within the Catholic Church.[23] While his ultimate self-sacrifice of his life was most certainly considered saintly and heroic, he was not killed strictly speaking out of odium fidei (hatred of the faith), but as the result of an act of Christian charity. Pope Paul VI himself had recognized this distinction at his beatification by naming him a Confessor and giving him the unofficial title "martyr of charity". Pope John Paul II, however, when deciding to canonize him, overruled the commission he had established (which agreed with the earlier assessment of heroic charity), wishing to make the point that the systematic hatred of (whole categories of) humanity propagated by the Nazi regime was in itself inherently an act of hatred of religious (Christian) faith, meaning Kolbe's death equated to martyrdom.[23]

Kolbe has also been accused of antisemitism based on the content of newspapers he was involved with, as they printed articles about topics such as a Zionist plot for world domination.[24][25][26] Slovenian sociologist Slavoj Žižek criticized Kolbe's activities as "writing and organizing mass propaganda for the Catholic Church, with a clear anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic edge."[25][27] However, a number of writers pointed out that the "Jewish question played a very minor role in Kolbe's thought and work".[25][25][28] On those grounds allegations of Kolbe's antisemitism have been denounced by Holocaust scholars Daniel L. Schlafly, Jr. and Warren Green, among others.[25]

During World War II Kolbe's monastery at Niepokalanów sheltered Jewish refugees,[25] and, according to a testimony of a local: "When Jews came to me asking for a piece of bread, I asked Father Maximilian if I could give it to them in good conscience, and he answered me, 'Yes, it is necessary to do this, because all men are our brothers.'"[18][28]

Nonetheless Kolbe has been "often vilified in Jewish literature as an avowed anti-Semite", despite "hundreds of testimonials of gratitude for the assistance ... several from the survivors of the Polish Jewish community".[18] Kolbe's alleged antisemitism was a source of the controversy in the 1980s in the aftermath of his canonization.[29] Kolbe is not recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.[21]

Relics

First-class relics of Kolbe exist, in the form of hairs from his head and beard, preserved without his knowledge by two friars at Niepokalanów who served as barbers in his friary between 1930 and 1941.[30] Since his beatification in 1971, more than 1,000 such relics have been distributed around the world for public veneration.[30] Second-class relics such as his personal effects, clothing and liturgical vestments, are preserved in his monastery cell and in a chapel at Niepokalanów, and may be viewed by visitors.[30]

Influence

Kolbe's influence has found fertile ground in his own Order of Conventual Franciscan friars, in the form of continued existence of the Militia Immaculatae movement.[31] In recent years new religious and secular institutes have been founded, inspired from this spiritual way. Among these the Missionaries of the Immaculate Mary – Father Kolbe, the Franciscan Friars of Mary Immaculate, and a parallel congregation of Religious Sisters, and others. The Franciscan Friars of Mary Immaculate are even taught basic Polish so they can sing the traditional hymns sung by Kolbe, in the saint's native tongue.[32] According to the friars,

Our patron, St. Maximilian Kolbe, inspires us with his unique Mariology and apostolic mission, which is to bring all souls to the Sacred Heart of Christ through the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Christ's most pure, efficient, and holy instrument of evangelization – especially those most estranged from the Church.[32]

Kolbe's views into Marian theology echo today through their influence on Vatican II.[2] His image may be found in churches across Europe.[22] Several churches in Poland are under his patronage, such as the Sanctuary of Saint Maxymilian in Zduńska Wola or the Church of Saint Maxymilian Kolbe in Szczecin.[33][34] A museum, Museum of St. Maximilian Kolbe "There was a Man", was opened in Niepokalanów in 1998.[35]

In 1963 Rolf Hochhuth published a play significantly influenced by Kolbe's life and dedicated to him, The Deputy.[16] In 2000, the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (U.S.) designated Marytown, home to a community of Conventual Franciscan friars, as the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe. Marytown is located in Libertyville, Illinois, and also features the Kolbe Holocaust Exhibit.[36] The Polish Senate declared the year 2011 to be the year of Maximilian Kolbe.[37]

Immaculata prayer

Kolbe composed the Immaculata prayer as a prayer of consecration to the Immaculata, i.e. the immaculately conceived Virgin Mary.[38]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Biographical Data Summary". Consecration Militia of the Immaculata. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Saints Index; Catholic Forum.com, Saint Maximilian Kolbe

- ^ "Holy Mass at the Brzezinka Concentration Camp". Vatican. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Armstrong, Regis J.; Peterson, Ingrid J. (2010). The Franciscan Tradition. Liturgical Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8146-3922-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Czesław Lechicki, Kolbe Rajmund, Polski Słownik Biograficzny, Tom XIII, 1968, p. 296

- ^ Strzelecka, Kinga (1984). Maksymilian M. Kolbe: für andere leben und sterben (in German). S[ank]t-Benno-Verlag. p. 6.

- ^ Armstrong, Regis J.; Peterson, Ingrid J. (2010). The Franciscan Tradition. Liturgical Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8146-3922-1.

- ^ a b Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Catholic-Pages.com

- ^ Czupryk, Father Cornelius (1935). "18th Anniversary Issue". Mugenzai no Seibo no Kishi. Mugenzai no Sono Monastery.

- ^ "Daily Prayers". Marypages.com. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Blessed Maximilian Kolbe-Priest Hero of a Death Camp by Mary Craig". Ewtn.com. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ a b Hepburn, Steven. "Maximilian Kolbe's story shows us why sainthood is still meaningful". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Łęcicki, Grzegorz (2010). "Media katolickie w III Rzeczypospolitej (1989–2009)". Kultura Media Teologia (in Polish). 2 (2). Uniwersytet Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego: 12–122. ISSN 2081-8971. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Historia". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "SP3RN @". qrz.com. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Czesław Lechicki, Kolbe Rajmund, Polski Słownik Biograficzny, Tom XIII, 1968, p. 297

- ^ "Kolbe, Saint of Auschwitz". Auschwitz.dk. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Paul, Mark, January 2010. Wartime Rescue of Jews by the Polish Catholic Clergy. The Testimony of Survivors, Polish Educational Foundation in North America, 2009, pp.23–24. [1]

- ^ "Sixty-ninth Anniversary of the Death of St. Maximilian Kolbe". Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

https://thevalueofsparrows.com/2013/05/16/faith-the-volunteer-at-auschwitzwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Plunka, Gene A. (24 April 2012). Staging Holocaust Resistance. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-137-00061-3.

- ^ a b "Maximilian Kolbe". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ a b Peterson, Anna L. (1997). Martyrdom and the Politics of Religion: Progressive Catholicism in El Salvador's Civil War. SUNY Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7914-3182-5.

- ^ Dershowitz, Alan M. (1 May 1992). Chutzpah. Simon and Schuster. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-671-76089-2.

- ^ a b c d e f "Scholars Reject Charge St. Maximilian Was Anti-semitic". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ Michael, Robert (1 April 2008). A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-230-61117-7.

- ^ Zizek, Slavoj (22 May 2012). Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. Verso Books. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-1-84467-902-7.

- ^ a b "Becky Ready". ewtn.com.

- ^ Yallop, David (23 August 2012). The Power & the Glory. Constable & Robinson Limited. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4721-0516-5.

- ^ a b c "The First-Class Relics of St Maximilian Kolbe". Pastoral Centre. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Catholic Way Publishing (27 December 2013). My Daily Prayers. Catholic Way Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-78379-029-6.

- ^ a b "O.F.M.I. Friars". Franciscan Friars of Mary Immaculate. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "Sanktuarium Św. Maksymiliana – Zduńska Wola – DIECEZJA WŁOCŁAWSKA -KURIA DIECEZJALNA WŁOCŁAWSKA". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ [http://www.smmkolbe.pl "Parafia p.w. �w. M.M. Kolbego w Szczecinie – Aktualności"]. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: replacement character in|title=at position 14 (help) - ^ "Niepokalanów". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ UCHWAŁA SENATU RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ z dnia 21 października 2010 r.o ogłoszeniu roku 2011 Rokiem Świętego Maksymiliana Marii Kolbego [2]

- ^ "University of Dayton Marian prayers". Campus.udayton.edu. 24 March 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

Sources

- Rees, Laurence. Auschwitz: A New History, Public Affairs, 2005. ISBN 1-58648-357-9

External links

- Patron Saints Index: Saint Maximilian Kolbe

- Kolbe's Gift, a play by David Gooderson about Kolbe and his self-sacrifice in Auschwitz based on factual evidence and conversations with the late Józef Garliński

- A Man Feared by the 21st Century: Saint Maximilian Kolbe from the Starvation Bunker in Auschwitz – a drama by Kazimierz Braun

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, a popular biography at Catholicism.org

- Niepokalanów in English

- Catholic Online, St. Maximilian Kolbe, Catholic Online.Inform-Inspire-Ignite.

- St. Maximilian Kolbe Website

- The Volunteer at Auschwitz

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- 1894 births

- 1941 deaths

- 20th-century Roman Catholic priests

- 20th-century Christian saints

- 20th-century Roman Catholic martyrs

- Anglican saints

- Canonizations by Pope John Paul II

- Catholic saints and blesseds of the Nazi era

- Conventual Friars Minor

- Executed Widerstand Catholics

- Martyred Roman Catholic priests

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- People from Zduńska Wola

- Polish civilians killed in World War II

- Polish people of German descent

- Polish people who died in Auschwitz concentration camp

- Polish Roman Catholic priests

- Polish Roman Catholic saints

- Pontifical Gregorian University alumni

- Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure alumni

- Religious workers who died in Nazi concentration camps

- Roman Catholic activists