USS Housatonic (1861)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Housatonic |

| Namesake | The Housatonic River |

| Builder | Boston Navy Yard, Charlestown, Massachusetts |

| Launched | 20 November 1861 |

| Sponsored by | Miss Jane Coffin Colby and Miss Susan Paters Hudson |

| Commissioned | 29 August 1862 |

| Fate | Sunk 17 February 1864 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Screw sloop |

| Displacement | 1,240 long tons (1,260 t) |

| Length | 205 ft (62 m) |

| Beam | 38 ft (12 m) |

| Draft | 8 ft 7 in (2.62 m) |

| Propulsion | Sail and steam |

| Speed | 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph) |

| Complement | 160 officers and enlisted |

| Armament |

|

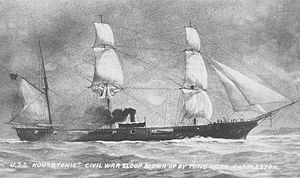

The first USS Housatonic was a screw sloop-of-war of the United States Navy. Named for the Housatonic River of New England, Housatonic was the first ship to be sunk by a submarine.

Housatonic was launched on 20 November 1861, by the Boston Navy Yard at Charlestown, Massachusetts, sponsored by Miss Jane Coffin Colby and Miss Susan Paters Hudson; and commissioned there on 29 August 1862, with Commander William Rogers Taylor in command. Housatonic was one of four sister ships which included USS Adirondack, USS Ossipee, and USS Juniata.

Service history

Blockading Charleston

Housatonic departed Boston on 11 September and arrived at Charleston, South Carolina, on 19 September to join the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. She took station outside the bar.

Capture of the Princess Royal and Confederate Counter-Attack

On 29 January 1863, her boats, aided by those of USS Augusta, USS G. W. Blunt, and USS America, boarded and refloated the iron steamer Princess Royal. The gunboat Unadilla had driven the blockade runner ashore as she attempted to slip into Charleston from England with a cargo consisting of two marine engines destined for Confederate ironclads and a large quantity of ordnance and ammunition. These imports were of such great potential value to the South that they have been called "the war's most important single cargo of contraband."

It is possibly in the hope of recovering this invaluable prize that the Confederate ironclad rams CSS Chicora and CSS Palmetto State slipped out of the main ship channel of Charleston Harbor to attack the Union blockading fleet in the early morning fog two days later. They rammed Mercedita, forcing her to strike her colors "in a sinking and perfectly defenseless condition", and moved on to cripple Keystone State. Gunfire from the rams also damaged Quaker City and Augusta before the Confederate ships withdrew under fire from Housatonic to the protection of shore batteries.

Capture of the Georgiana

On 19 March 1863, Housatonic and Wissahickon, responding to signal flares sent up by America, chased the 407 ton iron-hulled blockade runner SS Georgiana ashore on Long Island, South Carolina. The Georgiana's cargo of munitions, medicine and merchandise was then valued at over $1,000,000. The Georgiana was described in contemporary dispatches and newspaper accounts as more powerful than the Confederate cruisers Alabama, Shenandoah, and Florida. This was a serious and very important blow to the Confederacy. The wreck of the Georgiana was discovered by pioneer underwater archaeologist Lee Spence in 1965.

Further captures, and attacks on Charleston

Housatonic captured the sloop Neptune on 19 April as she attempted to run out of Charleston with a cargo of cotton and turpentine. She was credited with assisting in the capture of the steamer Seesh on 15 May. Howitzers mounted in Housatonic's boats joined in the attack on Fort Wagner on 10 July, which began the continuing bombardment of the Southern works at Charleston. In ensuing months her crew repeatedly manned boats which shelled the shoreline, patrolled close ashore gathering valuable information, and landed troops for raids against the outer defenses of Charleston.

Sunk in the first submarine attack

At just before 9PM, 17 February 1864, Housatonic, commanded by Charles Pickering, was maintaining her station in the blockade outside the bar. Robert F. Flemming, Jr., a black landsman, first sighted an object in the water 100 yards off, approaching the ship.[1] "It had the appearance of a plank moving in the water," Pickering later reported. Although the chain was slipped, the engine backed, and all hands were called to quarters, it was too late. Within two minutes of the first sighting, the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley rammed her spar torpedo into Housatonic's starboard side, forward of the mizzenmast, in history's first successful submarine attack on a warship. Before the rapidly sinking ship went down, the crew managed to lower two boats which took all the men they could hold; most others saved themselves by climbing into the rigging which remained above water after the stricken ship settled on the bottom. Two officers and three men in Housatonic died. The Confederate submarine escaped but was lost with all hands not long after this action; new evidence announced by archaeologists in 2013 indicates that the submarine may have been much closer to the point of detonation than previously realized, thus damaging the submarine as well.[2]

The wreck of Housatonic was largely scrapped in the 1870s–1890s and her location was eventually removed from coastal navigation charts and lost to history. The anchor of Housatonic can be found at the office of Wild Dunes on the Isle of Palms.

See also

References

- ^ Hicks, Brian (January 2014). "One-Way Mission of the H. L. Hunley". U.S. Naval Institute. U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Brian Hicks, Hunley legend altered by new discovery, The Post and Courier, 28 January 2013, accessed 28 January 2013.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- Use dmy dates from February 2013

- Sloops of the United States Navy

- Ships of the Union Navy

- Ships built in Boston

- Shipwrecks of the Carolina coast

- Shipwrecks of the American Civil War

- Disasters in South Carolina

- Maritime incidents in 1864

- Ships sunk by submarines

- Archaeological sites in South Carolina

- Charleston County, South Carolina

- 1861 ships

- United States Navy Connecticut-related ships

- United States Navy Massachusetts-related ships