Sudetes

| Sudetes | |

|---|---|

View of the trail between Spindlerova Bouda and Vysoké Kolo from in the Giant Mountains of the Western Sudetes along the Polish-Czech border. | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Sněžka |

| Elevation | 1,603 m (5,259 ft) |

| Coordinates | 50°44′10″N 15°44′24″E / 50.73611°N 15.74000°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 300 km (190 mi) |

| Geography | |

| Countries | Poland, Czech Republic and Germany |

| States | Lower Silesia, Bohemia, Moravia, Czech Silesia and Saxony |

| Range coordinates | 50°30′N 16°00′E / 50.5°N 16°E |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Variscan orogeny |

The Sudetes /suːˈdiːtiːz/ are a mountain range in Central Europe. They are also known as the Sudeten after their German name and Sudety in Czech and Polish.

The range stretches from eastern Germany (West Lusatian Hill Country and Uplands) by Tripoint to south-western Poland and to northern Czech Republic. The highest peak of the range is Sněžka (Template:Lang-pl) in the Krkonoše (Polish: Karkonosze) mountains on the Czech Republic–Poland border, which is 1,603 metres (5,259 ft) in elevation. The current geomorphological unit in the Czech part of the mountain range is Krkonošsko-jesenická subprovincie ("Krkonoše-Jeseníky"). It is separated from the Carpathian Mountains by the Moravian Gate. The highest parts of the Sudetes are protected by national parks;[1] Karkonosze and Stołowe in Poland and Krkonoše in the Czech Republic.

The Krkonoše Mountains (also called the Giant Mountains) have experienced growing tourism for winter sports during the past ten years. Their skiing resorts are becoming a budget alternative to the Alps.

Etymology

The name Sudetes is derived from Sudeti montes, a Latinization of the name Soudeta ore used in the Geographia by the Greco-Roman writer Ptolemy (Book 2, Chapter 10) c. AD 150 for a range of mountains in Germania in the general region of the modern Czech republic.

There is no consensus about which mountains he meant, and he could for example have intended the Ore Mountains, joining the modern Sudetes to their west, or even (according to Schütte) the Bohemian Forest (although this is normally considered to be equivalent to Ptolemy's Gabreta forest.[2] The modern Sudetes are probably Ptolemy's Askiburgion mountains.[3]

Ptolemy wrote "Σούδητα" in Greek, which is a neuter plural. Latin mons, however, is a masculine, hence Sudeti. The Latin version, and the modern geographical identification, is likely to be a scholastic innovation, as it is not attested in classical Latin literature. The meaning of the name is not known. In one hypothetical derivation, it means Mountains of Wild Boars, relying on Indo-European *su-, "pig". A better etymology perhaps is from Latin sudis, plural sudes, "spines", which can be used of spiny fish or spiny terrain.

Subdivisions

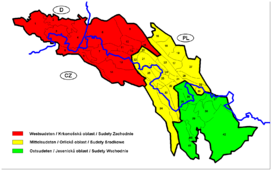

The Sudetes are usually divided into:

- Eastern Sudetes (Czech: Jeseníky) in the Czech Republic and Poland

- Oderské vrchy (Nízký Jeseník)

- Hrubý Jeseník (High Ash) Mountains with Mt. Praděd, 1,491 m (4,892 ft)

- Opawskie Mountains

- Golden Mountains

- Śnieżnik Mountains

- Hanušovická vrchovina

- Central Sudetes, in the Czech Republic and Poland

- Orlické Mountains with Mt. Velká Deštná, 1,115 m (3,658 ft)

- Bystrzyckie Mountains

- Bardzkie Mountains

- Table Mountains

- Owl Mountains

- Krucze Mountains

- Stone Mountains

- Waldenburg Mountains

- Ślęża massif

- Western Sudetes, in Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland

- Ještěd-Kozákov Ridge

- Jizera Mountains

- Kaczawskie Mountains

- Krkonoše (Giant Mountains) with Mt. Sněžka, 1,603 m (5,259 ft)

- Lusatian Mountains

- Rudawy Janowickie

- Lusatian Highlands

- Sudeten Foreland

High Sudetes (Template:Lang-pl, Template:Lang-cs, Template:Lang-de) is together name for the Krkonoše, Hrubý Jeseník and Śnieżnik mountain ranges. The Sudetes also comprise larger basins like the Jelenia Góra and the Kłodzko Valley.

Climate

The highest mountains, those located along the Czech-Polish border have annual precipitations around 1500 mm.[4] The Stołowe Mountains that reach 919 m have precipitations ranging from 750 mm at lower locations to 920 mm in the upper parts with July being the rainiest month.[5] Snow cover at the Stołowe Mountains typically last 70 to 95 days depending on altitude.[5]

Vegetation

Settlement, logging and clearance has left forest pockets in the foothills with dense and continuous forest being found in the upper parts of the mountains.[1] Due to logging in the last centuries little remains of the broad-leaf trees like beech, sycamore, ash and littleleaf linden that were once common in the Sudetes. Instead Norway spruce was planted in their place in the early 19th century, in some places amounting to monocultures.[1] To provide more space for spruce plantations various peatlands were drained in the 19th and 20th century.[5] Some spruce plantations have suffered severe damage as the seeds used came from lowland specimens that were not adapted to mountain conditions.[1] Silver fir grow naturally in the Sudetes being more widespread in past times, before clearance since the Late Middle Ages and subsequent industrial pollution reduced the stands.[6]

The higher mountains of the Sudetes lie above the timber line which is made up of Norway spruce.[4][7] Spruces in wind-exposed areas display features such as flag tree disposition of branches, tilted stems and elongated stem cross sections.[8] Forest-free areas above the timber line have increased historically by deforestation[9] yet lowering of the timber line by human activity is minimal.[7] Areas above the timber line appear discontinuously as "islands" in the Sudetes.[4] At Krkonoše the timer line lies at c. 1230 m a.s.l. while to the southeast in the Hrubý Jeseník mountains it lie at c. 1310 m a.s.l.[4] Part of the Hrubý Jeseník mountains have been above the timber line for no less than 5000 years.[4]

Many arctic-alpine and alpine vascular plants have a disjunct distribution being notably absent from the central Sudetes despite suitable habitats. Possibly this is the result a warm period during the Holocene (last 10,000 years) which wiped out cold-adapted vascular plants in the medium-sized mountains of the cetral Sudetes where there was no higher ground that could serve as refugia.[9][A] Besides altitude the distribution of some alpine plants is influenced by soil. This is the case of Aster alpinus that grows preferentially on calcareous ground.[9] Other alpine plants such as Cardamine amara, Epilobium anagallidifolium, Luzula sudetica and Solidago virgaurea occur beyond their altitudinal zonation in very humid areas.[9]

Peatlands are common in the mountains occurring on high plateaus or in valley bottoms. Fens occur at slopes.[5]

Geology

Bedrock

The igneous and metamorphic rocks of the Sudetes originated during the Variscan orogeny and its aftermath.[10] The Sudetes are the northeasternmost accessible part of Variscan orogen as in the North European Plain the orogen is buried beneath sediments.[11] Plate tectonic movements during the Variscan orogeny assembled together four major and two to three lesser tectonostratigraphic terranes.[12][B] The assemblage of the terranes ought to have involved the closure of at least two ocean basins containing oceanic crust and marine sediments.[13] This is reflected in the ophiolites, MORB-basalts, blueschists and eclogites that occur in-between terranes.[12] Various terranes of the Sudetes are likely extensions of the Armorican terrane while other terranes may be the fringes of the ancient Baltica continent.[11]

Once the main phase of deformation of the orogeny was over sedimentary basins that formed in-between metamorphic rock massifs were filled by sedimentary rock in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods.[13] Also during and after sedimentation large granitic plutons intruded the crust. Viewed in a map today these plutons make up about 15% the Sudetes.[10][13] Granites are of S-type.[11] The granites and grantic-gneisses of Izera in the west Sudetes are disassociated from orogeny and thought to have formed during rifting along a passive continental margin.[14][C] The Karkonosze Granite, also in the west Sudetes, have been dated to have formed c. 318 million years ago at the beginning of the Variscan orogeny.[15] The Karkonosze Granite is intruded by somewhat younger lamprophyre dykes.[15]

A NW-SE to WNW-ESE oriented strike-slip fault —the Intra-Sudetic fault— runs through the length of the Sudetes.[13] The Intra-Sudetic fault is parallel with the Upper Elbe fault and Middle Odra fault.[11]

Volcanism and thermal waters

There are remnants of lava flows and volcanic plugs in the Sudetes.[16] The volcanic rocks making up these outcrops are of mafic chemistry and include basanite and represent episodes of volcanism in the Oligocene and Miocene periods[D] that affected not only the Sudetes but also parts of the Sudetic foreland being part of a SW-NE oriented Bohemo-Silesian Belt of volcanic rocks.[16] Mantle xenoliths have been recovered from the lavas of a volcano at Ještěd-Kozákov Ridge in the Czech western Sudetes.[17] These pyroxenite xenoliths arrived to surface from approximate depths of 35, 70 and 73 km and indicate a complex history for the mantle beneath the Sudetes.[17]

There are thermal springs in the Sudetes with measured temperatures of 29 to 44 °C. Drilling has revealed the existence of waters at 87 °C at depths of 2000 m. These modern waters are believed to be associated to the Late Cenozoic volcanism in Central Europe.[18]

Uplift and landforms

The Sudetes forms the NE border of the Bohemian Massif.[11] In detail the Sudetes is made up of a series of massifs that are rectangular and rhomboid in plan view.[19] These mountains corresponds to horsts and domes separated by basins, including grabens.[20] The mountains took their present form after the Late Mesozoic retreat of the seas from the area which left the Sudetes subject to denudation for at least 65 million years.[19] This meant that during the Late Cretaceous and Early Cenozoic 8 to 4 km of rock was eroded from the top of what is now the Sudetes.[21] Concurrently with the Cenozoic denudation the climate cooled due to the northward drift of Europe. The collision between Africa and Europe has resulted in the deformation and uplift of the Sudetes.[19] As such the uplift is related to the contemporary rise of the Alps and Carpathians.[19][22][E] Uplift was accomplished by the creation or reactivation of numerous faults leading to a reshaping of the relief by renewed erosion.[10] Various "hanging valleys" attest to this uplift.[22]

Weathering during the Cenozoic led to the formation of an etchplain developed in parts of Sudetes. While this etchplain has been eroded various landforms and weathering mantles have been suggested to attest its former existence.[10] At present the mountain range shows a remarkable diversity of landforms.[19] Some of the landforms present are escarpments, inselbergs, bornhardts, granitic domes, tors, flared slopes and weathering pits.[10] Various escarpments have originated from faults and may reach hights of up to 500 m.[22]

During the Quaternary glaciations parts of the Sudetes remained free from glacier ice developing permafrost soils and periglacial landforms such as rock glaciers, nivation hollows, patterned ground, blockfields, solifluction landforms, blockstreams, tors and cryoplanation terraces.[7] The occurrence or not of these periglacial landforms depends on altitude, the steepness and direction of slopes and the underlying rock type.[7]

Geological research has been hampered by the multinational geography of the Sudetes with and the limitation of studies to state boundaries.[22][F]

History

The area around the Sudetes had by the 12th century been relatively densely settled[1] with agriculture and settlements expanding further in the High Middle Ages from the 13th century onward.[5] As this trend went on thinning of forest and deforestation had turned clearly unsustainable by the 14th century.[6] In the 15th and 16th centuries agriculture had reached the inner part of Stołowe Mountains in the Central Sudetes.[1] Destruction and degradation of the Sudetes forest peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries[6] with demand of firewood coming from glasshouses that operated through the area in the early modern period.[1]

Some limited form of forest management begun in the 18th century[6] while in the industrial age demand for firewood was sustained by metallurgic industries in the settlements and cities around the mountains.[1] In the 19th century the Central Sudetes had an economic boom with sandstone quarrying and a flourishing tourism industry centered on the natural scenery. Despite of this there was at least since the 1880s a trend of depopulation of villages and hamlets which continued into the 20th century.[23] Since World War II various areas that were cleared of forest have been re-naturalized.[23] Industrial activity across Europe has caused considerable damage to the forests as acid rain and heavy metals has arrived with westerly and southwesterly winds.[1] Silver firs have proven particularly vulnerable to industrial soil contamination.[6]

Sudetes and "Sudetenland"

After World War I the name Sudetenland came into use to describe areas of the First Czechoslovak Republic with large ethnic German populations. In 1918 the short-lived rump state of German-Austria proclaimed a Province of the Sudetenland in northern Moravia and Austrian Silesia around the city of Opava (Troppau).

The term was used in a wider sense when on 1 October 1933 Konrad Henlein founded the Sudeten German Party and in Nazi German parlance Sudetendeutsche (Sudeten Germans) referred to all indigenous ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia. They were heavily clustered in the entire mountainous periphery of Czechoslovakia—not only in the former Moravian Provinz Sudetenland but also along the northwestern Bohemian borderlands with German Lower Silesia, Saxony and Bavaria, in an area formerly called German Bohemia. In total the German minority population of pre-World War II Czechoslovakia numbered around 20% of the total national population.

Sparking a "Sudeten Crisis", Hitler got his future enemies to concede the Sudetenland with most of the Czechoslovak border fortifications in the 1938 Munich Agreement, leaving the remainder of Czechoslovakia shorn of its natural borders and buffer zone, finally occupied by Germany in March 1939. After being annexed by Nazi Germany, much of the region was redesignated as the Reichsgau Sudetenland.

After World War II, most of the German population within the Polish and Czechoslovak Sudetes was forcibly expelled on the basis of the Potsdam Agreement and the Beneš decrees. A considerable proportion of the Czechoslovak populace thereafter strongly objected to the use of the term Sudety. In the Czech Republic the designation Krkonošsko-jesenická subprovincie is used officially and in maps etc. usually only the discrete Czech names for the individual mountain ranges (e.g. Krkonoše) appear, as under Subdivisions above.

Economy and tourism

Part of the economy of the Sudetes is dedicated to tourism. Coal mining towns like Wałbrzych have re-oriented their economies towards tourism since the decline of mining in the 1980s.[24] As of 2000 scholar Krzysztof R. Mazurski judged that the Sudetes, much like the Poland's Baltic coast and the Carpathians, were unlikely to attract much foreign tourism.[24] Sandstone has been quarried in Sudetes during the 19th and 20th centuries.[23] Likewise volcanic rock has also been quarried.[16] Sandstone labyrinths have been a notable tourist attraction since the 19th century with considerable investments being done in projecting trails some of which involve rock engineering.[23]

In the Sudetes there are many spa towns with sanatoria. In many places the developed tourist base - hotels, guest houses, ski infrastructure.

The nearest international airport is in Wrocław - Copernicus Airport Wrocław.

Notable towns

Notable towns in this area include:

- Jelenia Góra (Poland)

- Karpacz (Poland)

- Szklarska Poręba (Poland)

- Świeradów-Zdrój (Poland)

- Kłodzko (Poland)

- Polanica-Zdrój (Poland)

- Duszniki-Zdrój with Zieleniec (Poland)

- Kudowa-Zdrój (Poland)

- Lądek-Zdrój (Poland)

- Sokołowsko (Poland)

- Harrachov (Czech Republic)

- Špindlerův Mlýn (Czech Republic)

- Žacléř (Czech Republic)

- Vrchlabí (Czech Republic)

- Zittau (Germany)

Image gallery

-

"Hell" on Szczeliniec Wielki, Table Mountains

-

Góry Sokole

-

Starościńskie Skały in Rudawy Janowickie

See also

- Mount Ślęża

- Main Sudetes Trail

- Książ

- Wambierzyce

- Kłodzko Fortress

- Srebrna Góra

- Chojnik

- Niesytno Castle

- Grüssau Abbey

- Izera railway

- Lower Silesian Voivodeship

- Tourism in Poland

- Crown of Polish Mountains

Notes

- ^ Not to be confused with a glacial refugium.

- ^ Geologist Tom McCann lists the main Variscan terranes that make up much of the Sudetes as the Moldanubian, Góry-Sowie-Klodzko, Teplá Barriandian, Lusatia-Izera terrane, Brunovistulian terrane. The first three lie in the central Sudetes while the last two in the west and central Sudetes.[13]

- ^ Contrary to this case S-type granites are typically thought to come into existence concurrently or slightly after orogeny.[14]

- ^ Some volcanic rocks may be as young as of Early Pliocene age.[16]

- ^ Fission track dating yields various possibilities about the Late Cenozoic uplift of the Sudetes. Possibly the last uplift pulse begun 7 to 5 million years ago.[21]

- ^ Alfred Jahn's geomorphological studies of the Polish Sudetes in 1953 and 1980 exemplify this.[22]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mazurski, Krzysztof R. (1986). "The destruction of forests in the polish Sudetes Mountains by industrial emissions". Forest Ecology and Management. 17: 303–315. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(86)90158-1.

- ^ Schütte, Ptolemy's maps of northern Europe, a reconstruction of the prototype, p. 141

- ^ Schütte, Ptolemy's maps of northern Europe, a reconstruction of the prototype, p. 56

- ^ a b c d e Treml, Václav; Jankovská, Vlasta; Libor, Petr (2008). "Holocene dynamics of the alpine timberline in the High Sudetes". Biologia. 63 (1): 73–80. doi:10.2478/s11756-008-0021-3.

- ^ a b c d e Glina, Bartłomiej; Malkiewicz, Małgorzata; Mendyk, Łukasz; Bogacz, Adam; Woźniczka, Przemysław (2016). "Human‐affected disturbances in vegetation cover and peatland development in the late Holocene recorded in shallow mountain peatlands (Central Sudetes, SW Poland)". Boreas. 46: 294–307. doi:10.1111/bor.12203.

- ^ a b c d e Barzdajn, Wladyslaw (2004). "Rehabilitation of silver fir (Abies alba Mill) populations in the Sudetes". Report of the second (20–22 September 2001, Valsaín, Spain) and third (17–19 October 2002, Kostrzyca, Poland) meetings (Report). pp. 45–51.

{{cite report}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|authors=(help) - ^ a b c d Křížek, M. (2007). "Periglacial landforms above the alpine timberline in the High Sudetes" (PDF). In Goudie, A.S.; Kalvoda, J. (eds.). Geomorphological variations. Praha: ProGrafiS Publ. pp. 313–338.

- ^ Wistuba, Małgorzata; Papciak, Tomasz; Malik, Ireneusz; Barnaś, Agnieszka; Polowy, Marta; Pilorz, Wojciech (2014). "Wzrost dekoncentryczny świerka pospolitego jako efekt oddziaływania dominującego kierunku wiatru (przykład z Hrubégo Jeseníka, Sudety Wschodnie)" [Eccentric growth of Norway spruce trees as a result of prevailing winds impact (example from Hrubý Jeseník, Eastern Sudetes)]. Studia i Materiały CEPL w Rogowie (in Polish). 40 (3): 63–73.

- ^ a b c d Kwiatkowski, Paweł; Krahulec, František (2016). "Disjunct Distribution Patterns in Vascular Flora of the Sudetes". Ann. Bot. Fennici. 53: 91–102. doi:10.5735/085.053.0217.

- ^ a b c d e Migoń, Piotr (1996). "Evolution of granite landscapes in the Sudetes (Central Europe): some problems of interpretation". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 107: 25–37. doi:10.1016/s0016-7878(96)80065-4.

- ^ a b c d e Mazur, Stanisław; Alexandrowski, Paweł; Kryza, Ryszard; Oberc-Dziedzic, Teresa (2006). "The Variscan Orogen in Poland". Geological Quarterly. 50 (1): 89–118.

- ^ a b Mazur, S.; Aleksandrowski, P. (2002). "Collage tectonics in the northeasternmost part of the Variscan Belt: the Sudetes, Bohemian Massif". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 201: 237–277.

- ^ a b c d e McCann, Tom (2008). "Sudetes". In McCann, Tom (ed.). The Geology of Central Europe. Vol. Volume 1: Pre-Cambrian and Palaeozoic. London: The Geological Society. p. 496. ISBN 978-1-86239-245-8.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Oberc-Dziedzic, T.; Pin, C.; Kryza, R. (2005). "Early Palaeozoic crustal melting in an extensional setting: petrological and Sm–Nd evidence from the Izera granite-gneisses, Polish Sudetes". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 94 (3): 354–368. doi:10.1007/s00531-005-0507-y.

- ^ a b Awdankiewicz, Marek; Awdankiewicz, Honorata; Kryza, Ryszard; Rodinov, Nickolay (2009). "SHRIMP zircon study of a micromonzodiorite dyke in the Karkonosze Granite, Sudetes (SW Poland): age constraints for late Variscan magmatism in Central Europe". Geological Magazine. 147 (1): 77–85. doi:10.1017/S001675680999015X.

- ^ a b c d Birkenmajer, Krzysztof; Pécskay, Zóltan; Grabowski, Jacek; Lorenc, Marek W.; Zagożdżon, Paweł P. (2002). "Radiometric dating of the Tertiary volcanics in Lower Silesia, Poland. II. K-Ar and palaeomagnetic data from Neogene basanites near Lądek Zdrój, Sudetes Mts". Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae. 72: 119–129.

- ^ a b Ackerman, Lukáš; Petr, Špaček; Medaris, Jr., Gordon; Hegner, Ernst; Svojtka, Martin; Ulrych, Jaromír (2012). "Geochemistry and petrology of pyroxenite xenoliths from Cenozoic alkaline basalts, Bohemian Massif" (PDF). Journal of Geosciences. 57: 199–219. doi:10.3190/jgeosci.125.

- ^ Dowgiałło, Jan (2000). "The Sudetic geothermal region of Poland–new findings and further prospects" (PDF). Proceedins of the World Geothermal Congress. World Geothermal Congress. Kyushu–Tohoku, Japan. pp. 1089–1094.

- ^ a b c d e Migoń, Piotr (2011). "Geomorphic Diversity of the Sudetes - Effects of the structure and global change superimposed". Geographia Polonica. 2: 93–105.

- ^ Migoń, Piotr (1997). "Tertiary etchsurfaces in the Sudetes Mountains, SW Poland: a contribution to the pre-Quaternary morphology of Central Europe". In Widdowson, M. (ed.). Palaeosurfaces: Recognition, Reconstruction and Palaeoenvironmental Interpretation. Geological Society Special Publication. London: The Geological Society.

- ^ a b Aramowicz, Aleksander; Anczkiewicz, Aneta A.; Mazur, Stanisław (2006). "Fission-track dating of apatite from the Góry Sowie Massif, Polish Sudetes, NE Bohemian Massif: implications for post-Variscan denudation and uplift" (PDF). N. Jb. Miner. Abh. 182 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1127/0077-7757/2006/0046.

- ^ a b c d e Różycka, Milena; Migoń, Piotr (2017). "Tectonic geomorphology of the Sudetes Mountains (Central Europe) — A review and re-apprisal". Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae. 87: 275–300. doi:10.14241/asgp.2017.016.

- ^ a b c d Migoń, Piotr; Latocha, Agnieszka (2013). "Human interactions with the sandstone landscape of central Sudetes". Applied Geography. 42: 206–216. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.03.015.

- ^ a b Mazurski, Krzysztof R. (2000). "Geographical perspectives on Polish tourism". GeoJournal. 50 (2/3): 173–179. doi:10.1023/a:1007180910552.