Ireland as a tax haven

Ireland is labelled a tax haven or a corporate tax haven, which it rejects. Ireland's base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") tools give foreign corporates effective tax rates of 0% to 3% on all globally re-routed profits, and are the largest BEPS flows in the world. Ireland's QIAIF regime, and Section 110 SPVs, enable foreign investors to avoid Irish taxes on Irish assets, and can be combined with Irish BEPS tools to create confidential routes out of the Irish corporate taxation system. While these structures are OECD-whitelisted, Ireland uses data protection and privacy laws, as well as opt-outs from the filing of public accounts, to obscure their effects. There is evidence Ireland behaves like a § Captured state willing to foster and protect tax avoidance strategies. Ireland features on all tax haven lists from academic and non-governmental organisations. Ireland does not meet the 1998 OECD definition of a tax haven, but no OECD member, including Switzerland, has ever met this definition and only Trinidad & Tobago met it in 2017. Similarly, no EU-28 country is amongst the 64 listed in the 2017 EU tax haven blacklist and greylist. Brazil became the first G20 country to blacklist Ireland as a tax haven in 2017.

Research attributes tolerance of Ireland as a corporate tax haven to be a result of § Political compromises arising from the traditional U.S. "worldwide" corporate tax system. The passing of the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act ("TCJA"), and move to a hybrid "territorial" tax system, has removed some of the need for these compromises. Forecast 2019 net effective corporate tax rates for IP-heavy U.S. multinationals are similar, whether they are legally based in Ireland or the U.S. While the TCJA neutralises some Irish BEPS tools, it has enhanced others (e.g. Apple's "Green Jersey"). A reliance on U.S. corporates (80% of corporate tax, 25% of direct labour, and 57% of OECD value-add), is a concern in Ireland.

Ireland’s traditional weakness in attracting non-U.S. corporates, or any corporates from full "territorial" tax systems (Table 1), was apparent in its 2017-18 failure to attract London financial services firms due to Brexit. However, Ireland’s expansion into traditional tax haven tools (e.g. QIAIFs, LQIAIFs, and Section 110 SPVs), has seen tax-driven law firms, including offshore magic circle law firms, setting up Irish offices to handle Brexit-driven tax restructuring. These tax haven-type tools have enabled Ireland to become the world's 4th largest shadow banking centre, and 5th largest Conduit OFC.

Source of labels

Ireland has been labeled a tax haven, or a corporate tax haven (or conduit ofc), by:

- The three academic leaders in tax haven study:[2] Hines (1994, 2007, 2010),[3][4][5] Dharmapala (2006 and 2009),[6] and Zucman (2015 and 2018);[7][8][9] and influential studies by CORPNET in 2017 (Conduit and Sink OFCs)[10][11][12] and by the IMF in 2018;[13] and by academic tax-policy centres in Germany,[14] the U.K.,[15] the UN,[16] and Ireland;[17]

- The three main non-governmental tax organisations: Tax Justice Network,[18][19][20] the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy,[21][22] and Oxfam;[23][24]

- The two U.S. Congressional investigations into global tax havens: 2008 by the Government Accountability Office,[25] and 2015 by the Congressional Research Service.[26]

- The 2013 U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommitte on Investigation ("PSI") into tax avoidance activities of U.S. multinationals by using "profit shifting" BEPS tools;[27][28][29]

- The three main published books on tax havens in the last decade: Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works, by Ronen Palan and Richard Murphy from 2010,[30] Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World, by Nicholas Shaxson from 2011, and The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens, by Gabriel Zucman from 2015.

- The main financial media: New York Times,[31] Bloomberg,[32] the Wall Street Journal,[33] Forbes,[34] the Financial Times,[35] and the Economist;[36]

- Some leading economists;[37][38][39][40][41]

- One G20 economy, Brazil, who blacklisted Ireland as a tax haven in 2017;[42][43] and potentially the U.S. State of Oregon whose Department of Revenue recommend blacklisting Ireland in 2017.[44]

Ireland has also been labelled related terms to being a tax haven:

- In Germany, the related term tax dumping has been used against Ireland by German political leaders;[45][46]

- The Financial Stability Forum ("FSF") and the International Monetary Fund ("IMF") listed Ireland as an offshore financial centre in 2000;[18][47][30]

- Bloomberg, in an article on PwC Ireland's managing partner Feargal O'Rourke, used the term tax avoidance hub;[48]

- The 2013 U.S Senate PSI Levin-McCain investigation into U.S. multinational tax, as well as labelling Ireland a tax haven, called Ireland the holy grail of tax avoidance;[49][50]

- Because the OECD has never listed any of its 35 members as tax havens, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland are referred to as the OECD tax havens;[51]

- Because the EU has never listed any of its 28 members as tax havens, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Belgium are referred to as the four EU tax havens.[52]

The term tax haven has been used by the Irish mainstream media and leading Irish commentators.[53][54][55][56][57] Irish elected TDs have asked the question: "Is Ireland a tax haven?".[58][59] A search of Dáil Éireann debates lists 871 references to the term.[60] Some established Irish political parties accuse the Irish State of tax haven activities.[61][62][63]

The international community at this point is concerned about the nature of tax havens, and Ireland in particular is viewed with a considerable amount of suspicion in the international community for doing what is considered - at the very least - on the boundaries of acceptable practices.

— Ashoka Mody, Ex-IMF mission chief to Ireland, "Former IMF official warns Ireland to prepare for end to tax regime", 21 June 2018.[64]

Evidence used

Global U.S. BEPS hub

Brad Setser & Cole Frank (CoFR),[65] and led to the replacement of Irish GDP/GNP with GNI*.

Ireland ranks in all global lists of corporate tax havens, and features in all "proxy tests" for tax havens and "quantitative measures" of tax havens. The level of base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") by U.S. multinationals in Ireland is so large,[9] that in 2017 the Central Bank of Ireland abandoned GDP/GNP as a statistic to replace it with Modified gross national income (GNI*).[66][67] Economists note that Ireland's distorted GDP is now distorting the EU's aggregate GDP,[68] and has artificially inflated the trade-deficit between the EU and the US.[69] (see Table 1).

Ireland's IP-based BEPS tools use "intellectual property" ("IP") to "shift profits" from higher-tax locations, with whom Ireland has bilateral tax treaties, back into Ireland. Once in Ireland, these tools reduce Irish corporate taxes by re-routing to say Bermuda with the double Irish tool (e.g. as Google and Facebook do), or to Malta with the single malt tool (e.g. as Microsoft and Allergan do), or by writing-off internally created virtual assets against Irish corporate tax with the capital allowances for intangible assets tool (e.g. as Apple do post 2015). These BEPS tools give an Irish effective corporate tax rate of 0-3%. They are the world's largest tax tools, and exceed the aggregate BEPS flows of the Caribbean tax haven system.[70][71][72]

While IP-based BEPS tools are the majority of Irish BEPS flows, they were developed from Ireland's traditional expertise in inter-group contract manufacturing, or transfer pricing-based ("TP") BEPS tools (e.g. capital allowance schemes, inter-group cross-border charging), which provide material employment in Ireland (e.g. U.S. life sciences.[73]).[74][65][75] Some firms like Apple maintain expensive Irish contract manufacturing TP-based BEPS operations (vs. Asia), to give "substance" to their larger Irish IP-based BEPS tools.[76][77]

By refusing to implement the 2013 EU Accounting Directive (and invoking exemptions on reporting holding company structures until 2022), Ireland enables their TP and IP-based BEPS tools to structure as "unlimited liability companies" ("ULC") which do not have to file public accounts with the Irish CRO.[78][79]

Ireland's Debt-based BEPS tools (e.g. the Section 110 SPV), have made Ireland the 4th largest global shadow banking centre,[80] and have been used by Russian banks to circumvent sanctions.[81][82][83] Irish Section 110 SPVs offer "orphaning" to protect the identity of the owner, and to shield the owner from Irish tax (the Section 110 SPV is an Irish company). They were used by U.S. distressed debt funds to avoid billions in Irish taxes,[84][85][86] assisted by Irish tax-law firms using in-house Irish children's charities to complete the orphan structure,[87][88][89] which enabled the U.S. distressed debt funds to export the gains on their Irish assets, income and capital, free of any Irish taxes or duties, to Luxembourg and the Caribbean (see Section 110 abuse).[90][91]

Unlike the TP and IP-based BEPS tools, Section 110 SPVs must file public accounts with the Irish CRO, which was how the above abuses were discovered in 2016-17. In February 2018 the Central Bank of Ireland upgraded the little-used L-QIAIF regime to give the same tax benefits as Section 110 SPVs but without having to file public accounts. In June 2018, the Central Bank reported that €55 billion of U.S.-owned distressed Irish assets, equivalent to 25% of Irish GNI*, moved out of Irish Section 110 SPVs and into L-QIAIFs.[92]

Apple's Q1 2015 Irish restructure, post their €13 billion EU fine for avoiding Irish taxes from 2004-2014, is cited as a tax structure that integrates Irish IP-based, and Jersey Debt-based, BEPS tools.[93] Apple Ireland bought circa $300 billion of a "virtual" IP-asset from Apple Jersey.[65][94] The Irish "capital allowances for intangible assets" BEPS tool allows Apple Ireland to write-off this virtual IP-asset against future Irish corporation tax. The €26.220 billion jump in Irish intangible capital allowances claimed for 2015,[95] showed Apple Ireland is writing-off this IP-asset over a 10 year period. In addition, Apple Jersey gave Apple Ireland the $300 billion "virtual" loan to buy this virtual IP-asset from Apple Jersey.[93] Thus, Apple Ireland can claim additional Irish corporation tax relief on this loan interest, which is circa $20 billion per annum (Apple Jersey pays no tax on the loan interest it receives from Apple Ireland). These tools, created from virtual internal assets financed by virtual internal loans, give Apple circa €45 billion per annum in relief against Irish corporation tax.[94] Microsoft is preparing to copy Apple’s tax scheme,[96] known as "the Green Jersey".[93][94]

The U.S Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") GILTI-regime neutralises the Jersey Debt-based BEPS tool of this "Green Jersey" structure. However, because Irish intangible capital allowances are accepted as U.S. GILTI deductions, it now enables U.S. multinationals to achieve net effective U.S. corporate tax rates, via TCJA participation relief,[97] of 0 to 3% from the Irish IP-based capital allowances part of this "Green Jersey" BEPS structure (i.e. why Microsoft is about to use it[96]).[98][99]

Domestic tax tools

Ireland's Qualifying Investor Alternative Investment Fund ("QIAIF") regime is a range of five tax-free legal wrappers (ICAV, Investment Company, Unit Trust, Common Contractual Fund, Investment Limited Partnership).[100][101] Four of the five wrappers do not file public accounts with the Irish CRO, and therefore offer tax confidentiality and tax secrecy.[102][103] While they are regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland, like the Section 110 SPV, it has been shown many are effectively unregulated "brass plate" entities.[104][105][106][83][107] Under the 1942 Central Bank Secrecy Act, the Central Bank of Ireland cannot send the confidential information which QIAIFs must file with them to the Irish Revenue.[108]

QIAIFs have been used in tax avoidance on Irish assets,[109][110][111][112] on circumventing international regulations,[113] on avoiding tax laws in the EU and the U.S.[114][115] QIAIFs can be combined with Irish corporate BEPS tools (e.g. the Orphaned Super-QIF), to create routes out of the Irish corporate tax system to Luxembourg,[116] the main Sink OFC for Ireland.[117][118][119] It is asserted that a material amount of assets in Irish QIAIFs, and the ICAV wrapper in particular, are Irish assets being shielded from Irish taxation.[120][121] Offshore magic circle law firms (e.g. Walkers and Maples and Calder, who have set up offices in Ireland), market the Irish ICAV as a superior wrapper to the Cayman SPC (Maples and Calder claim to be a major architect of the ICAV),[122][123][124] and there are explicit QIAIF rules to help with re-domiciling of Cayman/BVI funds into Irish ICAVs.[125]

Captured state

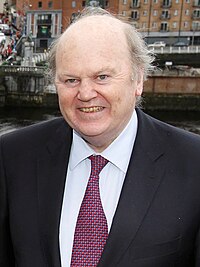

There is evidence Ireland meets the captured state criteria for tax havens.[105][127] When the EU investigated Apple in Ireland in 2016 they found private tax rulings from the Irish Revenue giving Apple a tax rate of 0.005% on +€100 billion of profits.[128][129] When the Irish Finance Minister Michael Noonan was alerted by an Irish MEP in 2016 to a new Irish BEPS tool to replace the double Irish (called the single malt), he was told to "put on the green jersey".[1] When Apple executed the largest BEPS transaction in history in Q1 2015 (see "leprechaun economics"), the Central Statistics Office suppressed data to hide Apple's indentity.[130] Noonan changed the capital allowances for intangible assets scheme rules, the IP-based BEPS tool Apple used in Q1 2015, to reduce Apple's effective tax rate from 2.5% to 0%.[131] When it was discovered in 2016 that U.S. distressed debt funds abused Section 110 SPVs to shield €80 billion in Irish loan balances from Irish taxes, the Irish State did not investigate or prosecute (see Section 110 abuse). The Central Bank of Ireland, who regulates Section 110 SPVs, does not look for tax avoidance. In February 2018, the Central Bank upgraded the little used L-QIAIF tax-free regime, which offers strong privacy from public scrutiny.[132] In June 2018, the U.S. distressed debt funds transferred €55 billion of Irish assets (over 25% of Irish GNI*), out of Section 110 SPVs and into confidential L-QIAIFs.[92]

The OCED's June 2017 Anti-BEPS MLI was signed by 70 jurisdictions.[133] The corporate tax havens, including Ireland, opted out of the key articles, and especially Article 12.[134]

Global legal firm Baker McKenzie,[135] representing a coalition of 24 multinational US software firms, including Microsoft, lobbied Michael Noonan, as [Irish] minister for finance, to resist the [OECD MLI] proposals in January 2017. In a letter to him the group recommended Ireland not adopt article 12, as the changes “will have effects lasting decades” and could “hamper global investment and growth due to uncertainty around taxation”. The letter said that “keeping the current standard will make Ireland a more attractive location for a regional headquarters by reducing the level of uncertainty in the tax relationship with Ireland’s trading partners”.

— Irish Times. "Ireland resists closing corporation tax ‘loophole’", 10 November 2017.[134]

Tax haven investigator Nicholas Shaxson documents how Ireland's captured state uses a complex, and "siloed", network of Irish privacy and Irish data protection laws to navigate around the fact that most of its tax tools are OECD-whitelisted,[136][137] and therefore must be transparent to some State entity.[138] For example, Irish QIAIFs (and L-QIAIFs) are regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and must provide the Bank with details of their financials. However, the 1942 Central Bank Secrecy Act prevents the Central Bank from sending this data to the Revenue Commissioners. Similarly, the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) stated it had to restrict its public data release in 2016-17 to protect the Apple's identity during its 2015 BEPS action, because the 1993 Central Statistics Act prohibits use of economic data for revealing such activities.[139] When the EU Commission fined Apple €13 billion for illegal State aid in 2016, there were no official records of any discussion of the tax deal given to Apple outside of the Irish Revenue Commissioners because such data is also protected.[140] When Tim Cook stated in 2016 that Apple was the largest tax-payer in Ireland, the Irish Revenue Commissioners quoted Section 815A of the 1997 Tax Acts that prevents them disclosing such information, even to members of Dail Eireann, or the Irish Department of Finance (despite the fact that Apple is circa one-fifth of Ireland's GDP).[141]

Commentators note the "plausible deniability" provided by Irish privacy and data protection laws, that enable the State to function as a tax haven while maintaining OECD compliance, and ensuring the Irish State entity that regulates each specific tax tool are fully "siloed" from any other Irish State body.[142][19][143]

Rebuttal of labels

Effective tax rates

The Irish State has refuted the tax haven labels as unfair criticism of its low, but legitimate, 12.5% Irish corporate headline tax rate,[144][145] which it defends as being the Irish corporate effective tax rate ("ETR").[146] Studies show that Ireland's aggregate effective corporate tax rate is circa 2-4%.[147][20][70][148] This lower aggregate effective tax rate is consistent with the individual effective tax rates of U.S. multinationals in Ireland (U.S.-controlled multinationals are 14 of Ireland's largest 20 companies, and Apple alone is over one-fifth of Irish GDP; see "low tax economy"),[17][149][150][151][152] as well as the IP-based BEPS tools openly marketed by the main tax-law firms in the Irish International Financial Services Centre with ETRs of 0-3% (see "effective tax rate").[153][154][155][156]

The Irish State does not refer to QIAIFs (or L-QIAIFs), or Section 110 SPVs, which allow non-resident investors to hold Irish assets indefinately without incurring Irish taxes, VAT or duties (e.g. permanent "base erosion" to the Irish exchequer as QIAIF units and SPV shares can be traded), and which can be combined with Irish BEPS tools to avoid all Irish corporate taxation (see § Domestic tax tools).

Salary taxes, VAT, and CGT for Irish residents are in line with rates of other EU-28 countries (if not higher). Ireland's approach to taxes is summarised by the OECD's "Hierarchy of Taxes" pyramid (reproduced in the Department of Finance Tax Strategy Group's 2011 tax policy document).[157] Ireland has a special lower salary tax scheme for employees of foreign multinationals ("SARP").[158]

OECD 1998 definition

EU and U.S. studies that attempted to find a consensus on the definition of a tax haven, have concluded that there is no consensus (see tax haven definitions).[159]

The Irish State, and its advisors, have refuted the tax haven label by invoking the 1998 OCED definition of a "tax haven" as the consensus definition:[160][161][162][163]

- No or nominal tax on the relevant income;

- Lack of effective exchange of information; (with OECD)

- Lack of transparency; (with OECD)

- No substantial activities (e.g. tolerance of brass plate companies).

Most Irish BEPS tools and QIAIFs are OECD-whitelisted (and can thus avail of Ireland's 70 bilateral tax treaties),[136][137] and therefore while Ireland could meet the first OECD test, it fails the second and third OECD tests. The fourth OECD test was withdrawn by the OECD in 2002 on protest from the U.S., which indicates is a political dimension to the definition.[18] In 2017, only one jurisdiction, Trinidad & Tobago, met the 1998 OECD definition of a tax haven (Trinidad & Tobago is not one of the 35 OECD member countries), and the definition has been subject to criticism.[164][165][166]

The noted tax haven academic James R. Hines Jr notes that OECD tax haven lists never include the 35 OECD member countries (Ireland is a founding OECD member).[3] The OECD definition was produced in 1998 as part of the OECD's investigation into Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue.[167] By 2000, when the OECD published their first list of tax havens,[168] it included no OECD member countries as they were now all considered to have engaged in the OECD's Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (see § External links). Because the OECD has never listed any of its 35 members as tax havens, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland are sometimes referred to as the "OECD tax havens".[51]

Subsequent definitions of tax haven, and/or offshore financial centre/corporate tax haven (see definition of a "tax haven"), focus on effective taxes as the primary requirement, which Ireland would meet, and have entered the general lexicon.[169][170][171] The Tax Justice Network, who places Ireland on its tax haven list,[18] split the concept of taxes from transparency by creating a secrecy jurisdictions and the Financial Secrecy Index. The OECD has never updated or amended its 1998 definition (apart from dropping the 4th criteria). The Tax Justice Network imply the U.S. may be the reason.[172]

EU tax haven lists

While by 2017, the OECD only considered Trinidad and Tobago to be a tax haven,[173] in 2017 the EU produced a list of 17 tax havens, plus another 47 jurisdictions on the "grey list",[174] however, as with the OECD lists above, the EU list did not include any EU-28 jurisdictions.[175] EU Commission was criticised for not including Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Malta and Cyprus[176][177]

Hines-Rice 1994 definition

The first major academic paper to produce a list of 41 tax havens, which included Ireland, was by James R Hines Jr and Eric M Rice in 1994.[5] Most academic papers into tax havens cite the Hines-Rice paper which is still regarded as important in the study of tax havens.[2] Hines has expanded his original 1994 list to 52 countries (papers in 2007 and 2010),[3][4] and Ireland still features in it. Subsequent major academic papers on tax havens by Dharmapala (2009, 2010),[6] and Zucman (2015, 2018)[7] cite the 1994 Hines-Rice paper, but create their own tax haven lists, all of which include Ireland.[7]

The Irish State, and related advisors, criticise modern academic studies on tax havens, which estimate Ireland to be the world's largest tax haven,[9] as being "out-of-date" because they cite the Hines-Rice paper.[178][179] In 2013, the Department of Finance (Ireland) commissioned an investigation into tax havens with the Department of the Revenue Commissioners and the state-sponsored Economic and Social Research Institute, who found the only sources of Ireland being a named a tax haven were from:[161]

- "First, because of Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporation tax rate"; (see § Effective tax rates)

- "Second, the role of the International Financial Services Centre in attracting investment to Ireland" (this is effectively also linked to § Effective tax rates);

- "Third, because of a rather obscure, but nonetheless influential paper by Hines and Rice dating back to 1994."

The following is from a 2018 Irish Independent article by the CEO of the key trade body that represents all U.S. multinationals in Ireland on the 1994 Hines-Rice paper:

However, it looks like the 'tax haven' narrative will always be with us - and typically that narrative is based on studies and data of 20 to 30 years' vintage or even older. It's a bit like calling out Ireland today for being homophobic because up to 1993 same-sex activity was criminalised and ignoring the joyous day in May 2015 when Ireland became the first country in the world to introduce marriage equality by popular vote.

Unique talent base

In a less technical manner to the rebuttals by the Irish State, the labels have also drawn responses from leaders in the Irish business community who attribute the value of U.S. investment in Ireland to Ireland’s unique talent base. At €334 billion, the value of U.S. investment in Ireland is larger than Ireland's 2016 GDP of €291 billion (or 2016 GNI* of €190 billion), and larger than all U.S. investment into the BRIC countries.[180] This unique talent base is also noted by IDA Ireland, the State body responsible for attracting inward investment, but never defined beyond the broad concept.[182]

Ireland has no university in the top 100.[183][184] Irish education does not appear to be distinctive.[185] Ireland has a high % of third-level graduates, but this is because it re-classified many technical colleges into degree-issuing institutions in 2005-08. This is believed to have contributed to the decline of its leading universities, of which there are barely two left in the top 200 (i.e. a quality over quantity issue).[186][187][188] Ireland continues to pursue this strategy and is considering re-classifying the remaining Irish technical institutes as universities for 2019.[189]

Ireland shows no apparent distinctiveness in any non-tax related metrics of business competitiveness including cost of living,[190][191][192] league tables of favoured EU FDI locations,[193] league tables of favoured EU destinations for London-based financials post-Brexit (which are linked to quality of talent),[194] and the key World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report rankings.[195]

Without its low-tax regime, Ireland will find it hard to sustain economic momentum

— Ashoka Mody, Ex-IMF mission chief to Ireland, "Warning that Ireland faces huge economic threat over corporate tax reliance - Troika chief", 9 June 2018.[196]

Global "knowledge hub" for "selling into Europe"

In another less technical rebuttal, the State explains Ireland's high ranking in the established "proxy tests" for tax havens as a by-product of Ireland's position as preferred hub for global "knowledge economy" multinationals (e.g. technology and life sciences), "selling into EU-28 markets".[197] When the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) suppressed its 2016-2017 data release to protect Apple's Q1 2015 BEPS action (i.e. leprechaun economics), it released a paper on "meeting the challenges of a modern globalised knowledge economy".[198]

Ireland has no non-U.S./non-U.K. multinationals in its top 50 companies by revenue, and only one by employees (German retailer Lidl who sells into Ireland).[199] The U.K. multinationals in Ireland are either also selling into Ireland (e.g. Tesco Ireland), or date pre-2009, after which the U.K. overhauled its tax system to a "territorial" model, and is now becoming a tax haven (see U.K. transformation);[200][201] post this change no major U.K. firms have moved to Ireland (Ireland has failed to win Brexit financial services firms).[194][202]

U.S.-controlled multinationals are 25 of the top 50 Irish firms (including tax inversions), and 70% of top 50 revenue (see Table 1). U.S. multinations pay 80% of Irish corporate taxes (see "low tax economy"). These Irish-based U.S. multinationals may be selling into Europe, however, the evidence is that they route all non-U.S. business through Ireland.[203][204] Ireland is more accurately described as a "U.S. corporate tax haven".[205] The U.S. multinationals in Ireland are from "knowledge industries" (see Table 1 below). This is because Ireland's BEPS tools (e.g. the double Irish, the single malt and the capital allowances for intangible assets) require intellectual property ("IP") to execute the BEPS actions, which technology and life sciences possess in quantity (see IP-Based BEPS tools).

Intellectual property (IP) has become the leading tax-avoidance vehicle.

— UCLA Law Review, "Intellectual Property Law Solutions to Global Coporate Tax Avoidance", (2015)[206]

Rather than a "global knowledge hub" for "selling into Europe", Ireland is a base for U.S. multinationals, with sufficient IP to use Ireland's BEPS tools, to shield non-U.S. revenues from U.S. taxation.

In 2018, the U.S. converted into a "territorial" tax system (the U.S. was one of the last remaining "worldwide" tax systems). Post this conversion, U.S. effective aggregate tax rates for IP-heavy U.S. multinationals is very similar to the effective tax rates they would incur if based in Ireland (even net of Irish BEPS tools). This represents a substantive challenge to the Irish economy (see effect of U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act).[207][208]

Ireland's recent expansion into traditional tax haven services (e.g. Cayman Island and Luxembourg type ICAVs and L-QIAIFs) is a diversifier from U.S. corporate tax haven services.[209] Brexit has been disappointing for Ireland in its failure to attract any London financial services firms, underlying Ireland’s traditional weakness in non-U.S. corporates. Brexit has led to growth in U.K. centric tax-law firms (including offshore magic circle firms), setting up offices in Ireland to handle traditional tax haven services for clients.[210]

| Rank (By Revenue) |

Company Name[199] |

Operational Base[211] |

Sector (if non-IRL)[199] |

Inversion (if non-IRL)[212] |

Revenue (2017 €bn)[199] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apple Ireland | technology | not inversion | 119.2 | |

| 2 | CRH | IRL | - | - | 27.6 |

| 3 | Medtronic plc | life sciences | 2015 inversion | 26.6 | |

| 4 | technology | not inversion | 26.3 | ||

| 5 | Microsoft | technology | not inversion | 18.5 | |

| 6 | Eaton | industrial | 2012 inversion | 16.5 | |

| 7 | DCC | IRL | - | - | 13.9 |

| 8 | Allergan Inc | life sciences | 2013 inversion | 12.9 | |

| 9 | technology | not inversion | 12.6 | ||

| 10 | Shire | life sciences | 2008 inversion | 12.4 | |

| 11 | Ingersoll-Rand | industrial | 2001 inversion | 11.5 | |

| 12 | Dell Ireland | technology | not inversion | 10.3 | |

| 13 | Oracle | technology | not inversion | 8.8 | |

| 14 | Smurfit Kappa | IRL | - | - | 8.6 |

| 15 | Ardagh Glass | IRL | - | - | 7.6 |

| 16 | Pfizer | life sciences | not inversion | 7.5 | |

| 17 | Ryanair | IRL | - | - | 6.6 |

| 18 | Kerry Group | IRL | - | - | 6.4 |

| 19 | Merck & Co | life sciences | not inversion | 6.1 | |

| 20 | Sandisk | technology | not inversion | 5.6 | |

| 21 | Boston Scientific | life sciences | not inversion | 5.0 | |

| 22 | Penneys | IRL | - | - | 4.4 |

| 23 | Total Produce | IRL | - | - | 4.3 |

| 24 | Perrigo | life sciences | 2013 inversion | 4.1 | |

| 25 | Experian | technology | 2007 inversion | 3.9 | |

| 26 | Musgrave | IRL | - | - | 3.7 |

| 27 | Kingspan | IRL | - | - | 3.7 |

| 28 | Dunnes Stores | IRL | - | - | 3.6 |

| 29 | Mallinckrodt Pharma | life sciences | 2013 inversion | 3.3 | |

| 30 | ESB | IRL | - | - | 3.2 |

| 31 | Alexion Pharma | life sciences | not inversion | 3.2 | |

| 32 | Grafton Group | IRL | - | - | 3.1 |

| 33 | VMware | technology | not inversion | 2.9 | |

| 34 | Abbott Laboratories | life sciences | not inversion | 2.9 | |

| 35 | ABP Food Group | IRL | - | - | 2.8 |

| 36 | Kingston Technology | technology | not inversion | 2.7 | |

| 37 | Greencore | IRL | - | - | 2.6 |

| 38 | Circle K Limited | IRL | - | - | 2.6 |

| 39 | Tesco Ireland | food retail | not inversion | 2.6 | |

| 40 | McKesson | life sciences | not inversion | 2.6 | |

| 41 | Peninsula Petroleum | IRL | - | - | 2.5 |

| 42 | Glanbia | IRL | - | - | 2.4 |

| 43 | Intel Ireland | technology | not inversion | 2.3 | |

| 44 | Gilead Sciences | life sciences | not inversion | 2.3 | |

| 45 | Adobe | technology | not inversion | 2.1 | |

| 46 | CMC Limited | IRL | - | - | 2.1 |

| 47 | Ornua Dairy | IRL | - | - | 2.1 |

| 48 | Baxter | life sciences | not inversion | 2.0 | |

| 49 | Paddy Power Betfair | IRL | - | - | 2.0 |

| 50 | Icon Plc | IRL | - | - | 1.9 |

| Total | 454.4 | ||||

From the above table:

- US-controlled firms are 25 of the top 50 and represent €317.8 billion of the €454.4 billion in total 2017 revenue (or 70%);

- Apple alone is over 26% of the total top 50 revenue and greater than all top 50 Irish companies combined (see leprechaun economics on Apple as one-fifth of Irish GDP);

- UK-controlled firms are 3 of the top 50 and represent €18.9 billion of the €454.4 billion in total 2017 revenue (or 4%), and Shire and Experian are pre the 2009-2012 U.K. transformation to a "territorial" tax system;

- Irish-controlled firms are 22 of the top 50 and represent €117.7 billion of the €454.4 billion in total 2017 revenue (or 26%);

- There are no other firms in the top 50 Irish companies from other jurisdictions.

Political compromises

Contradictions

While Ireland's development into traditional tax haven tools (e.g. ICAVs and L-QIAIFs) is more recent, Ireland's status as a corporate tax haven has been noted since 1994 (the first Hines-Rice tax haven paper),[5] and discussed in the U.S. Congress for a decade.[25] A lack of progress, and delays, in addressing Ireland's corporate tax BEPS tools is apparent:

- Ireland's most famous BEPS tool, the double Irish, which is attributed to creating the largest build-up in untaxed cash in history, was being documented in 2004.[213] It took over a decade for the EU-OECD to get Ireland to close the double Irish BEPS tool in 2015,[214] however, Ireland was given a further five-year delay to 2020 for existing users of the tool, which include Google and Facebook;[215]

- Ireland's replacement for the double Irish tool, the single malt, was already up and running in 2014 (and used by Microsoft and Allergan),[216][217] and has as yet not received any EU-OECD attention. It is noted that since the closure of the double Irish in 2015, the use of Irish BEPS tools increased materially;[218][219]

- The OECD, who is running a project since 2012 to stop global BEPS activities,[220] has made no comment on Apple's Q1 2015 $300 billion Irish BEPS action, the largest BEPS transaction in history (i.e. leprechaun economics), with Ireland's expanded capital allowances for intangible assets, BEPS tool;

- The U.S. administration condemned Apple's Irish tax structures in the 2013 Levin-McCain PSI,[27][28][29] however, it ran to Apple's defense when the EU Commission levied a €13 billion fine on Apple for Irish tax avoidance from 2004-2014, the largest corporate tax fine in history, arguing that Apple paying the full 12.5% Irish corporate tax rate would harm the U.S. exchequer;[221]

- Germany has condemned Ireland for its tax tools,[45] however, Germany is believed to have stalled the EU Commission's Digital Services Tax, and the German administration neutralised its own Parliment's 2018 "Royalty Barrier" by exempting all OECD approved IP schemes (i.e. all of Ireland's BEPS tools), see German Lizenzschranke;[222]

- Tax haven economist, Gabriel Zucman, showed in 2018 that most corporate tax disputes are between high-tax jurisdictions, and not between high-tax and low-tax corporate tax haven jurisdictions. In fact, Zucman's (et alia) analysis shows that disputes with the major corporate tax havens of Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, are rare.[223][7]

Reaolution of TCJA

Tax haven experts explain these contradictions as resulting from the different agendas of the major OECD taxing authorities, and particularly the U.S. and Germany, who rank #2 and #7 respectively, in the 2018 Financial Secrecy Index of tax secrecy jurisdictions:[7][224]

- U.S. Perspective. Pre the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA"), the U.S. had one of the highest global rates of corporation tax at 35%.[225] Allowing U.S. multinationals to "check-the-box" and use Irish BEPS tools on non-U.S. revenues was a compromise to keep U.S. multinationals from leaving the U.S.[226] The aggregate worldwide tax rates of U.S. multinationals is far lower than 35%. This compromise was not unanimously supported in Washington and some U.S. multinationals still inverted to Ireland.[212]

- EU Perspective I. The EU is the world's largest net exporting block. Many EU countries therefore also rely on IP-based BEPS tools to re-charge gross profits from global sales of automobiles, chemicals, and other exports, back to the EU. Because most EU countries run a "territorial" tax system, which allows lower tax rates for foreign sourced income, EU multinationals do not need to use Irish BEPS tools as the U.S. multinationals do;[227]

- EU Perspective II. A second noted EU perspective is that if U.S. multinationals need Ireland as a BEPS hub because the pre-TCJA U.S. "worldwide" tax system did not enable them to charge IP direct from the U.S. (without incurring larger U.S. taxes), then the money Ireland extracts from these U.S. multinationals (e.g. some Irish corporate taxes and Irish salaries), are still a net positive for the aggregate EU-28 economy.

Up until the passing of the TCJA in December 2017, the U.S. was one of eight jurisdictions to run a "worldwide" taxation system.[228] Ireland also operates a "worldwide" tax system. The other six jurisdictions who have "worldwide" tax systems are: Chile, Greece, Israel, Korea, Mexico, and Poland.

Post the TCJA, net effective tax rates for IP-heavy U.S.-controlled multinationals are similar, whether legally headquartered in Ireland or the U.S.[229][230] It is expected that Washington will be less accommodating to U.S. multinationals using Irish BEPS tools.[209] The EU Commission has also become less tolerant of U.S. multinational Irish tax strategies, as evidenced by the €13 billion fine on Apple for Irish tax avoidance from 2004-2014.

“Now that [U.S.] corporate tax reform has passed, the advantages of being an inverted company are less obvious”

— Jami Rubin, Managing Director and Head of Life Sciences Research Group, Goldman Sachs, March 2018,[230]

TCJA issues

While the Washington and EU political compromises tolerating Ireland as a corporate tax haven may be eroding, tax experts point to various technical flaws in the TCJA which, if not resolved, may actually enhance Ireland as a U.S. corporate tax haven:[98][99]

- Acceptance of Irish capital allowance charges in the GILTI calculation. Ireland's most powerful BEPS tool is the capital allowances for intangible assets scheme (i.e Apple's Green Jersey). Post TCJA, U.S. multinationals can achieve net effective U.S. tax rates of 0% to 3% via this Irish BEPS tool. In June 2018, Microsoft prepared a Green Jersey scheme.[96]

- Tax relief of 10% of Tangible Assets in the GILTI calculation.[98] This incentivises development of Irish infrastructure as the Irish tax code doubles this U.S. GILTI relief with Irish tangible capital allowances. Every $100 a U.S. multinational spends on Irish offices reduces their U.S. taxes by $42 ($21 & $21). In May-July 2018, Google doubled their Dublin hub.[231]

- Assessment of GILTI on an aggregate basis rather than a country-by-country basis.[99] Ireland's BEPS schemes generate large tax reliefs that net down the aggregate global income eligible for GILTI assessment, thus reducing TCJA’s anti-BEPS protections, and making Ireland’s BEPS tools a key part of U.S. multinational TCJA tax planning.

A June 2018 IMF country report on Ireland, while noting the significant exposure of Ireland's economy to U.S. corporates, concluded that the TCJA may not be as effective as Washington expects in addressing Ireland as a U.S. corporate tax haven.[232]

See also

- Corporation tax in the Republic of Ireland

- Corporate tax haven

- Tax haven

- Leprechaun economics Apple BEPS tool in Ireland

- Modified gross national income replace Irish GDP/GNP

- Green jersey agenda

- Feargal O'Rourke architect of Ireland's BEPS tools

- Matheson (law firm) Ireland's largest U.S. tax advisor

- Qualifying investor alternative investment fund (QIAIF) Irish tax free wrappers

- Double Irish IP-based BEPS tool

- Single Malt IP-based BEPS tool

- Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets IP-based BEPS tool

- Section 110 SPV Debt-based BEPS tool

- Conduit and Sink OFCs analysis of tax havens

- Panama as a tax haven

- United States as a tax haven

References

- ^ a b "Dáil Éireann debate - Thursday, 23 Nov 2017". House of the Oireachtas. 23 November 2017.

Pearse Doherty: It was interesting that when [MEP] Matt Carthy put that to the Minister's predecessor (Michael Noonan), his response was that this was very unpatriotic and he should wear the green jersey. That was the former Minister's response to the fact there is a major loophole, whether intentional or unintentional, in our tax code that has allowed large companies to continue to use the double Irish [called single malt].

- ^ a b "Banks in Tax Havens: First Evidence based on Country-by-Country Reporting" (PDF). EU Commission. July 2017. p. 50.

Figure D: Tax Haven Literature Review: A Typology

- ^ a b c James Hines (2010). "Treasure Islands". University of Michigan. p. 104.

Table 1: 52 Tax Havens

- ^ a b James Hines (2007). "Tax Havens" (PDF). University of Michigan.

There are roughly 45 major tax havens in the world today. Examples include Andorra, Ireland, Luxembourg and Monaco in Europe, Hong Kong and Singapore in Asia, and the Cayman Islands, the Netherlands Antilles, and Panama in the Americas.

- ^ a b c James Hines; Eric Rice (February 1994). "John Hines and Eric Rice. FISCAL PARADISE: FOREIGN TAX HAVENS AND AMERICAN BUSINESS" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics (Harvard/MIT).

We identify 41 countries and regions as tax havens for the purposes of U. S. businesses. Together the seven tax havens with populations greater than one million (Hong Kong, Ireland, Liberia, Lebanon, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland) account for 80 percent of total tax haven population and 89 percent of tax haven GDP.

- ^ a b Dhammika Dharmapala; James Hines (2009). "Which countries become tax havens?" (PDF). Journal of Public Economics.

- ^ a b c d e Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations". University of Berkley. p. 31.

Appendix Table 2: Tax Havens

- ^ "Zucman:Corporations Push Profits Into Corporate Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Gabrial Zucman Study Says". Wall Street Journal. 10 June 2018.

Such profit shifting leads to a total annual revenue loss of $200 billion globally

- ^ a b c "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- ^ "Uncovering Offshore Financial Centers:Conduits and Sinks in the Global Corporate Ownership Network". Nature. 24 July 2017.

- ^ "Offshore Financial Centers and the Five Largest Value Conduits in the World". CORPNET. 24 July 2017.

- ^ "The countries which are conduits for the biggest tax havens (Ireland is 5th)". RTE News. 25 September 2017.

A new University of Amsterdam CORPNET study has found that the Netherlands, the UK, Switzerland, Singapore and Ireland are the leading intermediary countries that corporations use to funnel their money to and from tax havens

- ^ "Piercing the Veil of Tax Havens VOL. 55, NO. 2". International Monetary Fund: Finance & Development Quarterly. June 2018.

The eight major pass-through economies—the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong SAR, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Ireland, and Singapore—host more than 85 percent of the world's investment in special purpose entities, which are often set up for tax reasons.

- ^ "GERMAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH: Dirty Money Coming Home: Capital Flows into and out of Tax Havens" (PDF). DIW BERLIN. 2017. p. 41.

Table A1: Tax havens full list:IRELAND

- ^ Ronen Palan (June 2013). "CITY UNIVERSITY PERC: The Governance of the Black Holes of the World Economy: Shadow Banking and Offshore Finance" (PDF). City, University of London. p. 11.

A Survey of surveys of the eleven best known and most authoritative lists of tax havens of the world found that Switzerland is considered as a tax haven by nine of them, Luxembourg and Ireland by eight, the Netherlands by two and Belgium by one

- ^ Petr Jansky; Miroslav Palansky (May 2017). "Estimating the Scale of Corporate Profit Shifting: Tax Revenue Losses Related to Foreign Direct Investment" (PDF). United Nations University. p. 5.

Countries traditionally perceived as tax havens (Cyprus, Ireland and the United Kingdom)

- ^ a b Professor Jim Stewart (2016). "TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BUSINESS SCHOOL: Irish MNC Tax Strategies" (PDF). Trinity College Dublin. p. 3.

Ireland meets all of these characteristics and togethr with Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland have been described as the four OECD tax havens.

- ^ a b c d "IDENTIFYING TAX HAVENS AND OFFSHORE FINANCE CENTRES: Various attempts have been made to identify and list tax havens and offshore finance centres (OFCs). This Briefing Paper aims to compare these lists and clarify the criteria used in preparing them" (PDF). Tax Justice Network. July 2017.

- ^ a b "How Ireland became a tax haven and offshore financial centre". Nicholas Shaxson, Tax Justice Network. 11 November 2015.

The willingness to brush dirt under the carpet to support the financial sector, and an equating of these policies with patriotism (sometimes known in Ireland as the Green Jersey agenda,) contributed to the remarkable regulatory laxity with massive impacts in other nations (as well as in Ireland itself) as global financial firms sought an escape from financial regulation in Dublin.

- ^ a b "TAX JUSTICE NETWORK: Ireland Financial Secrecy Index Country Report 2014" (PDF). Tax Justice Network. November 2014.

Misleadingly, studies cited by the Irish Times and other outlets suggest that the effective tax rate is close to the headline 12.5 percent rate – but this is a fictional result based on a theoretical 'standard firm with 60 employees' and no exports: it is entirely inapplicable to transnationals. Though there are various ways to calculate effective tax rates, other studies find rates of just 2.5-4.5 percent.

- ^ "Offshore Shell Games 2017" (PDF). Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy. 2017. p. 17.

- ^ "OFFSHORE SHELL GAMES REPORT: US firms are keeping billions in offshore 'tax havens' - and Ireland is high on the list". Fora, Sunday Business Post. 15 October 2016.

The study provided figures for the combined profits reported by American multinational corporations in '10 notorious tax havens' – a list that included Ireland, the Netherlands and Switzerland

- ^ "Ireland named world's 6th worst corporate tax haven". journal.ie. 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Oxfam says Ireland is a tax haven judged by EU criteria". Irish Times. 28 November 2017.

- ^ a b "INTERNATIONAL TAXATION: Large U.S. Corporations and Federal Contractors with Subsidiaries in Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions" (PDF). U.S. GAO. 18 December 2008. p. 12.

Table 1: Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions and the Sources of Those Jurisdictions

- ^ Jane Gravelle (15 January 2015). "Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion". Cornell University. p. 4.

Table 1. Countries Listed on Various Tax Haven Lists

- ^ a b Senator Carl Levin; Senator John McCain (21 May 2013). "Offshore Profit Shifting and the U.S. Tax Code - Part 2 (Apple Inc.)". US Senate. p. 3.

A number of studies show that multinational corporations are moving "mobile" income out of the United States into low or no tax jurisdictions, including tax havens such as Ireland, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands.

- ^ a b "Senators insists Ireland IS a tax haven, despite ambassador's letter: Carl Levin and John McCain have dismissed the Irish ambassador's account of Ireland's corporate tax system". thejournal.ie. 31 May 2013.

Senators LEVIN and McCAIN: Most reasonable people would agree that negotiating special tax arrangements that allow companies to pay little or no income tax meets a common-sense definition of a tax haven.

- ^ a b "Ireland rejects U.S. senator claims as tax spat rumbles on". Reuters. 31 May 2013.

- ^ a b Ronen Palan; Richard Murphy (2010). "Tax Havens and Offshore Financial Centres". Cornell University Press. p. 24.

Yet today it is difficult to distinguish between the activities of tax havens and OFCs.

- ^ "Tax Havens Blunt Impact of Corporate Tax Cut, Economists Say". New York Times. 10 June 2018.

Large corporations like Apple, Google, Nike and Starbucks all take steps to book profits in tax havens such as Bermuda and Ireland

- ^ "Weil on Finance: Yes, Ireland Is a Tax Haven". Bloomberg News. 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Dublin Moves to Block Controversial Tax Gambit". Wall Street Journal. 15 October 2013.

At least 125 major U.S. companies have registered several hundred subsidiaries or investment funds at 70 Sir John Rogerson's Quay, a seven-story building in Dublin's docklands, according to a review of government and corporate records by The Wall Street Journal. The common thread is the building's primary resident: Matheson, an Irish law firm that specializes in ways companies can use Irish tax law.

- ^ "If Ireland Is Not A Tax Haven, What Is It?". Forbes. November 2014.

- ^ "Tax avoidance: The Irish inversion". Financial Times. 29 April 2014.

That undermines Ireland's insistence that it is not a tax haven, making it more difficult to defend its system in an international climate that is turning sharply against tax avoidance.

- ^ "Still slipping the net Europe's corporate-tax havens say they are reforming. Up to a point". Economist. 8 October 2015.

The Netherlands, and other low-tax havens such as Ireland and Luxembourg, have attracted much criticism from other countries for the legal loopholes they leave open to encourage such tax avoidance by big corporations.

- ^ Joseph Stiglitz (2 September 2016). "'Cheating' Ireland, muddled Europe". The Irish Examiner.

- ^ Lawrence Summers (22 October 2017). "One last time on who benefits from corporate tax cuts". The Washington Post.

These examples feel far more relevant to the corporate tax issue analysis than comparisons to small economies and tax havens like Ireland and Switzerland upon which the CEA relies

- ^ Gabriel Zucman (8 November 2017). "The desperate inequality behind global tax dodging". The Guardian.

Our research shows that six European tax havens alone (Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Malta and Cyprus) siphon off a total of €350bn every year

- ^ "WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM: 'That's a joke', 'stealing': Ireland's low corporate tax rate criticised by leading economists at Davos". journal.ie. 28 January 2018.

IRELAND'S CORPORATE TAX rate has come under heavy criticism at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

- ^ Yanis Varoufakis (12 June 2018). "Ireland a tax haven 'free-riding' on Europe". Irish Times.

- ^ "Blacklisted by Brazil, Dublin funds find new ways to invest". Reuters. 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America". Tax Justice Network. 6 April 2017.

- ^ "Oregon Department of Revenue made a recommendation that Ireland be included as a 'listed jurisdiction' or tax haven". Irish Independent. 26 March 2017.

- ^ a b "German-Irish relationship faces stress over tax-avoidance measures: German coalition parties name Irish-based tech giants in vow to tackle tax fraud and avoidance". Irish Times. 13 January 2018.

SPD parliamentary secretary Carsten Schneider called Irish "tax dumping" a "poison for democracy" ahead of a vote which saw the Bundestag grant Ireland's request

- ^ "German party rejects Irish loan repayment plan that could save €150m". Irish Times. 17 November 2017.

"We won't go along with this free pass for Ireland because we don't want ongoing tax dumping in the EU. We're not talking about Ireland's 12.5 per cent tax rate here, but secret deals that reduce that tax burden to near zero."

- ^ Ronen Palan (4 April 2012). "Tax Havens and Offshore Financial Centres" (PDF). University of Birmingham.

Some experts see no difference between tax havens and OFCs, and employ the terms interchangeably.

- ^ "Man Making Ireland Tax Avoidance Hub Proves Local Hero". Bloomberg. 28 October 2013.

Google Inc., Facebook Inc. and LinkedIn Corp. wound up in Ireland because they could reduce their tax bills. Their success is leading European and U.S. politicians to label the country a tax haven that must change its ways

- ^ "The 'Holy Grail of tax avoidance schemes' was made in the US". Irish Times. 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Ireland is Apple's 'Holy Grail of tax avoidance': The firm pays just two per cent tax on profits in Ireland but has denied using any "tax gimmicks"". journal.ie. 23 May 2013.

- ^ a b Francis Weyzig (2013). "Tax treaty shopping: structural determinants of FDI routed through the Netherlands" (PDF). International Tax and Public Finance. p. 6.

The four OECD member countries Luxembourg, Ireland, Belgium and Switzerland, which can also be regarded as tax havens for multinationals because of their special tax regimes.

- ^ Francis Weyzig (October 2017). "The Nasty Four must show their real colours". International Tax and Public Finance.

- ^ Diarmuid Ferriter (16 June 2018). "Semantics and Ireland's tax status Department of Finance persists in denying Ireland is world's biggest tax haven".

Despite such developments, "Team Ireland" has constantly dismissed the descritpion of Ireland as a tax haven, even when the extent of that haven is patently obvious.

- ^ "IRISH TIMES EDITORIAL Corporate tax: defending the indefensible". The Irish Times. 2 December 2017.

There is a broad consensus that Ireland must defend its 12.5 per cent corporate tax rate. But that rate is defensible only if it is real. The great risk to Ireland is that we are trying to defend the indefensible. It is morally, politically and economically wrong for Ireland to allow vastly wealthy corporations to escape the basic duty of paying tax. If we don't recognise that now, we will soon find that a key plank of Irish policy has become untenable.

- ^ "The United States' new view of Ireland: 'tax haven'". Irish Times. January 2017.

- ^ Fintan O'Toole (16 April 2016). "US taxpayers growing tired of Ireland's one big idea". Irish Times.

- ^ "Is Ireland a one-trick pony by enticing corporations with low taxes? Cillian Doyle says Ireland is a tax haven and we should change our ways before the decisions are taken out of our hands". journal.ie. 21 January 2016.

And as the UN's Philip Aston says, 'when lists of tax havens are drawn up, Ireland is always prominently among them'. The US Senate similarly found that by any 'common sense definition of a tax haven' Ireland easily met the criteria. I mean when Forbes regularly ranks you in their list of 'Top ten tax havens', there's not really much of a debate to be had.

- ^ "Is Ireland a tax haven for corporations?". Clare Daly TD. 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Is Ireland a tax haven?". Richard Boyd Barrett TD. August 2013.

- ^ "Dail Eireann Oireachtas Debates: Search".

- ^ "SINN FEIN: MEP McCarthy criticises EU tax haven blacklist as a whitewash". Sinn Fein. 6 December 2017.

- ^ "SINN FEIN: Irish state's tax haven activities contribute to obscene inequality". Sinn Fein. 18 October 2017.

- ^ "LABOUR PARTY: Time to 'definitively address' Ireland's tax haven reputation: Joan Burton drafts Bill to establish tax commission to rehabilitate State's 'last chance saloon' on tax justice". Irish Times. 3 July 2018.

- ^ ""The golden goose may be killed" - Former IMF official warns Ireland to prepare for end to tax regime". Newstalk Radio. 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments". Council on Foreign Relations. 25 April 2018.

- ^ "CSO paints a very different picture of Irish economy with new measure". Irish Times. 15 July 2017.

- ^ "New economic Leprechaun on loose as rate of growth plunges". Irish Independent. 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Ireland Exports its Leprechaun". Council on Foreign Relations. 11 May 2018.

Ireland has, more or less, stopped using GDP to measure its own economy. And on current trends [because Irish GDP is distorting EU-28 aggregate data], the eurozone taken as a whole may need to consider something similar.

- ^ "The Missing Profits of Nations∗" (PDF). Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Tørsløv, Ludvig Wier. 8 June 2018. p. 25.

Profit shifting also has a significant effect on trade balances. For instance, after accounting for profit shifting, Japan, the U.K., France, and Greece turn out to have trade surpluses in 2015, in contrast to the published data that record trade deficits. According to our estimates, the true trade deficit of the United States was 2.1% of GDP in 2015, instead of 2.8% in the official statistics—that is, a quarter of the recorded trade deficit of the United States is an illusion of multinational corporate tax avoidance.

- ^ a b "APPENDIX Table 2. Gabriel Zucman: The Missing Profits of Nations". University of Berkley. June 2018. p. 31.

Ireland's effective tax rate on all foreign corporates (U.S. and non-U.S.) is 4%

- ^ "Ireland named as world's biggest tax haven". The Times U.K. 14 June 2018.

Research conducted by academics at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Copenhagen estimated that foreign multinationals moved €90 billion of profits to Ireland in 2015 — more than all Caribbean countries combined.

- ^ "Fintan O'Toole: Ireland is becoming the tax haven of choice for profit-shifting multinationals". Irish Times. 16 June 2018.

- ^ "Tax deals raise questions over Ireland's growth spurt". Financial Times. 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Irish overseas 'contract manufacturing' mainly tax avoidance". FinFacts Ireland. 16 February 2015.

- ^ Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (19 March 2015). "The Growth Effect of 'Contract Manufacturing'". Economic Incentives.

- ^ "Revealed Eight facts you may not know about the Apple Irish plant". Irish Independent. 15 December 2017.

- ^ "Apple's multi-billion dollar, low-tax profit hub: Knocknaheeny, Ireland". The Guardian. 29 May 2013.

- ^ "New report: is Apple paying less than 1% tax in the EU?". Tax Justice Network. 28 June 2018.

The use of private "unlimited liability company" (ULC) status, which exempts companies from filing financial reports publicly. The fact that Apple, Google and many others continue to keep their Irish financial information secret is due to a failure by the Irish government to implement the 2013 EU Accounting Directive, which would require full public financial statements, until 2017, and even then retaining an exemption from financial reporting for certain holding companies until 2022

- ^ "Ireland's playing games in the last chance saloon of tax justice". Richard Murphy. 4 July 2018.

Local subsidiaries of multinationals must always be required to file their accounts on public record, which is not the case at present. Ireland is not just a tax haven at present, it is also a corporate secrecy jurisdiction.

- ^ "Ireland has world's fourth largest shadow banking sector, hosting €2.02 trillion of assets". Irish Independent. 18 March 2018.

- ^ "How Russian Firms Funnelled €100bn through Dublin via Section 110 SPVs". The Sunday Business Post. 4 March 2018.

- ^ "More than €100bn in Russian Money funneled through Dublin in SPVs". The Irish Times. 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b "TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN: Ireland, Global Finance and the Russian Connection" (PDF). Professor Jim Stewart Cillian Doyle. 27 February 2018. p. 21.

Regulation has been described as light touch regulation/unregulated

- ^ "Loophole lets firms earning millions pay €250 tax, Dáil told". Irish Times. 6 July 2016.

- ^ "Vulture funds pay just €8,000 in tax on €10 billion of assets". thejournal.ie. 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Revealed: How vulture funds paid €20k in tax on assets of €20bn". The Sunday Business Post. 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Vulture funds using charities to avoid paying tax, says Donnelly". Irish Times. 14 July 2016.

- ^ "Why would a Vulture Fund own a Children's Charity". Dail Eireann. 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Kinsella: Charity status for vulture funds - someone shout stop!". Sunday Business Post. 24 July 2016.

- ^ "SECTION 110 and QIAIFs: How do vulture funds manage to pay practically no tax in Ireland?". Emma Clancy. 30 July 2016.

- ^ "How do vulture funds exploit Irish tax loopholes?". Irish Times. 17 October 2016.

SPVs, QIAIFs and ICAVs. They're acronyms only corporate wonks could love. But they have entered the lexicon of the Dáil in recent months as Opposition members have highlighted how these corporate structures have been used to great advantage by so-called vulture funds to minimise taxes on property bought at bargain basement prices in recent years.

- ^ a b c "Tax-free funds once favoured by 'vultures' fall €55bn: Regulator attributes decline to the decision of funds to exit their so-called 'section 110 status'". Irish Times. 28 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "New Report on Apple's New Irish Tax Structure". Tax Justice Network. June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Apple's Irish Tax Deals". European United Left–Nordic Green Left. June 2018.

- ^ "An Analysis of 2015 Corporation Tax Returns and 2016 Payments" (PDF). Revenue Commissioners. April 2017.

- ^ a b c "Irish Microsoft firm worth $100bn ahead of merger". Sunday Business Post. 24 June 2018.

- ^ "A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act". Tax Foundation. 3 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Mihir A. Desai (June 2018). "Tax Reform: Round One". Harvard Magazine.

- ^ a b c Ben Harris (economist) (25 May 2018). "6 ways to fix the tax system post TCJA". Brookings Institution.

- ^ "KPMG Ireland: QIAIFs" (PDF). KPMG. November 2015.

- ^ "A Guide to Investing in QIAIFs" (PDF). Dillon Eustace. November 2015.

- ^ "QIAIFs Davy Stockbrokers Fund Services" (PDF). Davy Stockbrokers. 2015.

- ^ "Establishing a QIAIF in Ireland" (PDF). Matheson (law firm). 2014.

- ^ "A third of Ireland's shadow banking subject to little or no oversight: A report published on Wednesday by the Swiss-based Financial Stability Board". The Irish Times. 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Former Irish Central Bank Deputy Governor says Irish politicians mindless of IFSC risks". The Irish Times. 5 March 2018.

Irish politicians are "mindlessly in favour" of growing the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), according to a former deputy governor of the Central Bank

- ^ "TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN: 'Section 110' Companies. A Success story for Ireland?" (PDF). Professor Jim Stewart Cillian Doyle. 12 January 2017. p. 20.

The same source in comparing different investment vehicles states that :- Another positive of the Section 110 Company is that there are no regulatory restrictions regarding lending as is the case with a QIF (Qualifying Investor Fund).

- ^ "IMF queries lawyers and bankers on hundreds of IFSC SPV boards". The Irish Times. 30 September 2016.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has raised concerns about instances where individual bankers and lawyers were appointed to hundreds of boards of unregulated special-purpose vehicles in Dublin's International Financial Services Centre.

- ^ "Powerful Central Bank secrecy laws limit public disclosure of key documents". Irish Times. January 2016.

- ^ "There are yet more Irish laws that allow foreign property investors to operate here tax-free". thejournal.ie. 10 September 2016.

Certain funds in operation here are seeing foreign property investors paying no tax on income. The value of property owned in these QIAIFs is in the region of €300 billion.

- ^ "Clerys owner exploits tax avoidance loophole: Majority of shuttered Dublin store owned by collective asset vehicle (ICAV)". Irish Times. 4 October 2016.

Icavs were introduced last year, following lobbying by the funds industry, to tempt certain types of offshore fund business to Ireland. It has since emerged, however, that the structures have been widely utilised to avoid tax on Irish property.

- ^ Mulligan, John (6 August 2016). "Kennedy Wilson firm pays no tax on its €1bn Irish property assets with QIAIFs". Irish Independent. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Central Bank landlord a vulture fund paying no Irish tax using a QIF, says SF". Irish Independent. 28 August 2016.

- ^ Nicholas Shaxson (29 May 2013). "Tax 'trickery' in Ireland: A safe haven you can bank on". Irish Times.

Ireland is a wonderful, special country in many ways. But when it comes to providing foreigners with lax financial regulation or tax trickery, it is a goddamned rogue state

- ^ "'Strong evidence' Ireland aiding EU banks' tax-avoidance schemes". Irish Independent. 28 March 2017.

The massive profitability levels of European banks in Ireland suggests that large profits may be reported in Ireland as a tax-avoidance strategy,

- ^ "Irish 'tax haven' benefits from offshore asset shifts, reports New York Federal Reserve". Irish Independent. 13 May 2018.

The massive profitability levels of European banks in Ireland suggests that large profits may be reported in Ireland as a tax-avoidance strategy,

- ^ "Ireland:Selected Issues". International Monetary Fund. June 2018. p. 20.

Figure 3. Foreign Direct Investment - Over half of Irish outbound FDI is routed to Luxembourg

- ^ "Ireland as a location for Distressed Debt: Orphaned Super QIF Example". Davy Stockbrokers. 2014.

- ^ "Irish SPV Taxation" (PDF). Grant Thornton. 30 September 2015.

Irish withholding tax on transfers to Luxembourg can be avoided if structured as a Eurobond

- ^ "Mason Hayes and Curran:Silver Linings from Ireland's Financial Clouds with QIAIFs and Section 110 SPVs" (PDF). Mason Hayes & Curran Law. May 2016.

- ^ "How foreign firms are making a killing in buying Irish property". Irish examiner. 22 August 2016.

The Irish Collective Asset-management Vehicle was a nifty little tax structure introduced last year. Designed to primarily facilitate the transfer of US funds into Dublin, it allows foreign investors to channel their investments through Ireland while paying no tax.

- ^ "Fears over tax leakage via investors' ICAV vehicles". Sunday Times. 26 February 2017.

Internal Department of Finance briefing documents reveal that officials believe there has been "extremely significant" tax leakage due to investors using special purpose vehicles.

- ^ "New Irish Fund Vehicle to Facilitate US Investment – the ICAV". Walkers (law firm). 2015.

- ^ "The ICAV – Maples and Calder Checks the Box". Maples and Calder. March 2016.

Since then we have retained our position as the leading Irish counsel on ICAVs and to date have advised on 30% of all ICAV sub-funds authorised by the Central Bank, which is nearly twice as many as our nearest rival.

- ^ "IRISH FUNDS ASSOCIATION: ICAV Breakfast Seminar New York" (PDF). Irish Funds Association. November 2015. p. 16.

ANDREA KELLY (PwC Ireland): "We expect most Irish QIAIFs to be structured as ICAVs from now on and given that ICAVs are superior tax management vehicles to the to Cayman Island SPCs, Ireland should attract substantial re-domiciling business

- ^ "Conversion of a BVI or Cayman Fund to an Irish ICAV". William Fry Law Firm. 1 October 2015.

- ^ "FEARGAL O'ROURKE: Man Making Ireland Tax Avoidance Hub Proves Local Hero". Bloomberg News. 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Tax Justice Network: Captured State". Tax Justice Network. November 2015.

How Ireland became an offshore financial centre

- ^ "State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth up to €13 billion". EU Commission. 30 August 2016.

The Commission's investigation concluded that Ireland granted illegal tax benefits to Apple, which enabled it to pay substantially less tax than other businesses over many years. In fact, this selective treatment allowed Apple to pay an effective corporate tax rate of 1 percent on its European profits in 2003 down to 0.005 percent in 2014.

- ^ Barrera, Rita; Bustamante, Jessica (2 August 2017). "The Rotten Apple: Tax Avoidance in Ireland". The International Trade Journal. 32. The International Trade Journal: 150. doi:10.1080/08853908.2017.1356250.

- ^ "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments". Council on Foreign Relations. 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Change in tax treatment of intellectual property and subsequent and reversal hard to fathom". Irish Times. 8 November 2017.

- ^ a b "CENTRAL BANK OF IRELAND: Enhancements to the L-QIAIF regime announced". Matheson (law firm). 29 November 2016.

- ^ "Turning the Tide: The OECD's Multilateral Instrument Has Been Signed" (PDF). SquirePattonBoggs. July 2017.

- ^ a b "Ireland resists closing corporation tax 'loophole'". Irish Times. 10 November 2017.

- ^ "After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits". New York Times. 6 November 2017.

A key architect [for Apple] was Baker McKenzie, a huge law firm based in Chicago. The firm has a reputation for devising creative offshore structures for multinationals and defending them to tax regulators. It has also fought international proposals for tax avoidance crackdowns.

- ^ a b "Tax Sandwich: Ireland's OECD-compliant tax tools" (PDF). Mason Hayes & Curran. 2014.

- ^ a b "Ireland as a domicile for QIAIFs" (PDF). Matheson (law firm). August 2016.

- ^ Nicholas Shaxson (2011). "Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Med who Stole the World". Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ "Official Statistics and Data Protection Legislation". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). 2018.

Confidentiality and use of information for statistical purposes: Information obtained under the Statistics Act is strictly confidential, under Section 33 of the Statistics Act, 1993. It may only be accessed by Officers of Statistics, who are required to sign a Declaration of Secrecy under Section 21.

- ^ "IRISH EX. TAOISEACH BERTIE AHERN: Revenue 'kept Apple tax deal from cabinet'". Sunday Times. 14 November 2016.

- ^ "FactCheck: Is Apple really the "largest taxpayer in Ireland"?". journal.ie. 4 September 2016.

Revenue said: "Interactions between Revenue and individual taxpayers are subject to the taxpayer confidentiality provisions of Section 851A".

- ^ "The capture of tax haven Ireland: "the bankers, hedge funds got virtually everything they wanted"". Nicholas Shaxson. May 2013.

- ^ Professor Philip Alston (13 February 2015). "'Nobody believes Ireland is not a tax haven' - UN official". Irish Times.

"The Irish authorities knew exactly what was going on, long before the international community finally blew the whistle.

- ^ "Irish Taoiseach rebuts Oxfam claim that Ireland is a tax haven". Irish Times. 14 December 2016.

But Mr Kenny noted that Oxfam included Ireland's 12.5 per cent corporation tax rate as one of the factors for deeming it a tax haven. "The 12.5 per cent is fully in line with the OECD and international best practice in having a low rate and applying it to a very wide tax base."

- ^ "'Ireland is not a tax haven': Department of Finance dismisses 'tax haven' research findings". thejournal.ie. 13 June 2018.

Suggestions that Ireland are a tax haven simply because of our longstanding 12.5% corporate tax rate are totally out of line with the agreed global consensus that a low corporate tax rate applied to a wide tax base is good economic policy for attracting investment and supporting economic growth.

- ^ "Effective Corporate Tax in Ireland: April 2014" (PDF). Department of Finance. April 2014.

- ^ "Effective Corporate Tax calculations: 2.2%". Irish Times. 14 February 2014.

A study by James Stewart, associate professor in finance at Trinity College Dublin, suggests that in 2011 the subsidiaries of US multinationals in Ireland paid an effective tax rate of 2.2 per cent.

- ^ "Ireland: Where Profits Pile Up, Helping Multinationals Keep Taxes Low". Bloomberg News. October 2013.

Meanwhile, the tax rate reported by those Irish subsidaries of U.S. companies plummeted to 3% from 9% by 2010

- ^ "Pinning Down Apple's Alleged 0.005% Tax Rate in Ireland Is Nearly Impossible". Bloomberg News. 1 September 2016.

- ^ "'Double Irish' and 'Dutch Sandwich' saved Google $3.7bn in tax in 2016". Irish Times. 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Facebook Ireland pays tax of just €30m on €12.6bn". Irish Examiner. 29 November 2017.

- ^ "Oracle paid just €11m tax on Irish turnover of €7bn". Irish Independent. 28 April 2014.

- ^ "Maples and Calder Irish Intellectual Property Tax Regime - 2.5% Effective Tax". Maples and Calder. February 2018.

Structure 1: The profits of the Irish company will typically be subject to the corporation tax rate of 12.5% if the company has the requisite level of substance to be considered trading. The tax depreciation and interest expense can reduce the effective rate of tax to a minimum of 2.5%.

- ^ "Ireland as a European gateway jurisdiction for China – outbound and inbound investments" (PDF). Matheson. March 2013.

The tax deduction can be used to achieve an effective tax rate of 2.5% on profits from the exploitation of the IP purchased. Provided the IP is held for five years, a subsequent disposal of the IP will not result in a clawback.

- ^ "Uses of Ireland for German Companies: Irish "Intellectual Property" Tax of 2.5%" (PDF). Arthur Cox Law Firm. January 2012. p. 3.

Intellectual Property: The effective corporation tax rate can be reduced to as low as 2.5% for Irish companies whose trade involves the exploitation of intellectual property. The Irish IP regime is broad and applies to all types of IP. A generous scheme of capital allowances in Ireland offers significant incentives to companies who locate their activities in Ireland. A well-known global company [Accenture in 2009] recently moved the ownership and exploitation of an IP portfolio worth approximately $7 billion to Ireland.

- ^ "World Intellectual Property Day: IRELAND'S 2.5% IP Tax Rate (Section 4.1.1)". Mason Hayes and Curran. April 2013.

- ^ "Tax Strategy Group: Irish Corporate Taxation" (PDF). October 2011. p. 3.

- ^ "Extension of SARP Scheme Tax incentives for foreign staff rejected". 29 December 2017.

Under the arrangement – known as the special assignee relief (Sarp) – 30% of income above €75,000 is exempt from income tax. Those who benefit are also allowed a €5,000 per child tax-free allowance for school fees, if those fees are paid by their employer

- ^ "Understanding the rationale for compiling 'tax haven' lists" (PDF). EU Parliament Research. December 2017. p. 3.

There is no single definition of a tax haven, although there are a number of commonalities in the various concepts used

- ^ "Irish Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe insists Ireland is not 'world's biggest tax haven': Report finds more multinational profits moved through Republic than the Caribbean". Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

IFAC member and economist Martina Lawless said on the basis of the OECD's criteria for tax havens, which are internationally recognised, Ireland was not one.

- ^ a b Gary Tobin (Finance); Keith Walsh (Revenue) (September 2013). "What Makes a Country a Tax Haven? An Assessment of International Standards Shows Why Ireland Is Not a Tax Haven" (PDF). Department of Finance (Ireland)/Economic and Social Research Institute Review. p. 403.

- ^ "Tom Maguire Tax Partner DELOITTE: Why Ireland's transparency and tax regime means it is not a haven". Irish Independent. February 2018.

The OECD outlined certain factors which in its view described a tax haven.

- ^ "Suzanne Kelly PAST PRESIDENT IRISH TAX INSTITUTE: There is a definition of a tax haven - and Ireland doesn't make that grade". Irish Independent. 2 February 2016.

The OECD stated that for a country to be a tax haven, it had to have certain characteristics.

- ^ "Trinidad & Tobago left as the last blacklisted tax haven". Financial Times. September 2013.

Alex Cobham of the Tax Justice Network said: It's disheartening to see the OECD fall back into the old pattern of creating 'tax haven' blacklists on the basis of criteria that are so weak as to be near enough meaningless, and then declaring success when the list is empty."

- ^ "Activists and experts ridicule OECD's tax havens 'blacklist' as a farce". Humanosphere. 30 June 2017.

One of the criteria, for example, is that a country must be at least "largely compliant" with the Exchange Of Information on Request standard, a bilateral country-to-country information exchange. According to Turner, this standard is outdated and has been proven to not really work.

- ^ "Oxfam disputes opaque OECD failing just one tax haven on transparency". Oxfam. 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue" (PDF). OECD. 1998.

- ^ "Towards Global Tax Co-Operation" (PDF). OECD. 2000.

- ^ "Financial Times Lexicon: Definition of tax haven:". Financial Times. June 2018.

A country with little or no taxation that offers foreign individuals or corporations residency so that they can avoid tax at home.

- ^ "Tax haven definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

A tax haven is a country or place which has a low rate of tax so that people choose to live there or register companies there in order to avoid paying higher tax in their own countries.

- ^ "Tax haven definition and meaning | Cambridge English Dictionary". Cambridge English Dictionary. 2018.

a place where people pay less tax than they would pay if they lived in their own country

- ^ "Empty OECD 'tax haven' blacklist undermines progress". Tax Justice Network. 26 June 2017.

- ^ "OECD tax chief: 'Ireland is not a tax haven'". thejournal.ie. 23 July 2013.

- ^ "EU blacklist names 17 tax havens and puts Caymans and Jersey on notice". The Guardian. 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Outbreak of 'so whatery' over EU tax haven blacklist". Irish Times. 7 December 2017.