Cathedral school

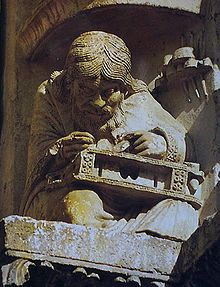

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these early cathedral schools, and more recent foundations, continued into modern times.

Early schools

In the later Roman Empire, as Roman municipal education declined, bishops began to establish schools associated with their cathedrals to provide the church with an educated clergy. The earliest evidence of a school established in this manner is in Visigothic Spain at the Second Council of Toledo in 527.[1] These early schools, with a focus on an apprenticeship in religious learning under a scholarly bishop, have been identified in other parts of Spain and in about twenty towns in Gaul (France) during the sixth and seventh centuries.[2]

During and after the mission of St Augustine to England, cathedral schools were established as the new dioceses were themselves created (Canterbury 597, Rochester 604, York 627 for example). This group of schools forms the oldest schools continuously operating. A significant function of cathedral schools was to provide boy trebles for the choirs, evolving into choir schools, some of which still function as such.

Charlemagne, king of the Franks and later Emperor, recognizing the importance of education to the clergy and, to a lesser extent, to the nobility, set out to restore this declining tradition by issuing several decrees requiring that education be provided at monasteries and cathedrals. In 789, Charlemagne's Admonitio Generalis required that schools be established in every monastery and bishopric, in which "children can learn to read; that psalms, notation, chant, computation, and grammar be taught."[3] Subsequent documents, such as the letter De litteris colendis, required that bishops select as teachers men who had "the will and the ability to learn and a desire to instruct others"[4] and a decree of the Council of Frankfurt (794) recommended that bishops undertake the instruction of their clergy.[5]

Subsequently, cathedral schools arose in major cities such as Chartres, Orleans, Paris, Laon, Reims or Rouen in France and Utrecht, Liege, Cologne, Metz, Speyer, Würzburg, Bamberg, Magdeburg, Hildesheim or Freising in Germany. Following in the earlier tradition, these cathedral schools primarily taught future clergy and provided literate administrators for the increasingly elaborate courts of the Renaissance of the 12th century. Speyer was renowned for supplying the Holy Roman Empire with diplomats.[6] The court of Henry I of England, himself an early example of a literate king, was closely tied to the cathedral school of Laon.[7]

Characteristics and development

Cathedral schools were mostly oriented around the academic welfare of the nobility's children. Because it was intended to train them for careers in the church, girls were excluded from the schools. Later on, many lay students who were not necessarily interested in seeking a career in the church wanted to enroll. Demand arose for schools to teach government, state, and other Church affairs. The schools, (some notable ones dating back to the eighth and ninth centuries) accepted fewer than 100 students. Pupils had to demonstrate substantial intelligence and be able to handle a demanding academic course load. Considering that books were also expensive, students were in the practice of memorizing their teachers' lectures. Cathedral schools at this time were primarily run by a group of ministers and divided into two parts: Schola minor which was intended for younger students would later become elementary schools. Then there was the schola major, which taught older students. These would later become secondary schools.

The subjects taught at cathedral schools ranged from literature to mathematics. These topics were called the seven liberal arts: grammar, astronomy, rhetoric (or speech), logic, arithmetic, geometry and music. In grammar classes, students were trained to read, write and speak Latin which was the universal language in Europe at the time. Astronomy was necessary for calculating dates and times. Rhetoric was a major component of a vocal education. Logic consisted of the criteria for sound or fallacious arguments, particularly in a theological context, and arithmetic served as the basis for quantitative reasoning. Students read stories and poems in Latin by authors such as Cicero and Virgil. Much as in the present day, cathedral schools were split into elementary and higher schools with different curricula. The elementary school curriculum was composed of reading, writing and psalmody, while the high school curriculum was trivium (grammar, rhetoric and dialect), the rest of the liberal arts, as well as scripture study and pastoral theology.

Cathedral schools today

While cathedral schools are no longer a significant site of higher education, many Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran cathedrals operate as primary or secondary schools. Most of those listed below are modern foundations, but a few trace their history to medieval schools.

Australia

- Bathurst – Cathedral Primary School

- Bunbury – Bunbury Cathedral Grammar School

- Perth – St George's Anglican Grammar School

- Rockhampton – The Cathedral College

- Sydney – St Andrew's Cathedral School

- Sydney – St Mary's Cathedral College

- Townsville – The Cathedral School of St Anne and St James

- Wangaratta – Cathedral College

Canada

Denmark

- Ribe – Ribe Katedralskole

- Aarhus – Aarhus Katedralskole

- Aalborg – Aalborg Katedralskole

- Viborg – Viborg Katedralskole

- Odense – Odense Katedralskole

- Roskilde – Roskilde Katedralskole

Finland

France

India

The Netherlands

Norway

- Bergen katedralskole

- Hamar katedralskole

- Kristiansand katedralskole

- Oslo katedralskole

- Stavanger katedralskole

- Trondheim katedralskole

Pakistan

- Punjab, Pakistan – Cathedral High School

South Africa

Sweden

- Linköping – Katedralskolan

- Lund – Katedralskolan

- Skara – Katedralskolan

- Uppsala – Katedralskolan

- Växjö – Katedralskolan

United Kingdom

England

- The seven King's Schools established, or re-endowed and renamed, by King Henry VIII in 1541, are located in Canterbury, Chester, Ely, Gloucester, Peterborough, Rochester and Worcester

- London – St Paul's Cathedral School (Anglican), Westminster Abbey Choir School (Anglican), Westminster Cathedral Choir School (Catholic)

- Bristol – Bristol Cathedral Choir School (a former cathedral school, it is now an academy)

- Chelmsford

- Chichester – The Prebendal School

- Durham – Chorister School

- Exeter – Exeter Cathedral School

- Hereford – Hereford Cathedral School

- Lichfield – Lichfield Cathedral School

- Oxford – Christ Church Cathedral School

- Salisbury – Salisbury Cathedral School

- Southwell – Southwell Minster School

- Wells – Wells Cathedral School

- Winchester – The Pilgrims' School

- York – The Minster School

Wales

- The Cathedral School, Llandaff

- St John's College, Cardiff (the United Kingdom's only Roman Catholic cathedral school which teaches up to Sixth Form)

United States

Among others:

- Arlington, Virginia – St. Thomas More Cathedral School

- Boston, Massachusetts – Cathedral High School

- Kalamazoo, Michigan – St. Augustine Cathedral School

- New York, New York – The Cathedral School, on the Upper East Side

- New York, New York – The Cathedral School of St. John the Divine

- Salt Lake City, Utah – St. Vincent DePaul Parish School

- Raleigh, North Carolina – Sacred Heart Cathedral School

- Washington D.C. – National Cathedral School (girls) / St. Albans School (Washington, D.C.) (boys) / Beauvoir School (elementary)

- Natchez, Mississippi - Cathedral Greenwave

See also

References

- ^ Riché 1978, pp. 126f.

- ^ Riché 1978, pp. 282–90

- ^ Pierre Riché, Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1988, p. 191. ISBN 0-8122-1096-4

- ^ Charlemagne: "De Litteris Colendis"

- ^ Pierre Riché, Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1988, pp. 192. ISBN 0-8122-1096-4

- ^ Geschichte der Stadt Speyer. Vol 1, Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-17-007522-5

- ^ C. Warren Hollister, Henry I (Yale English Monarchs), 2001 p. 25.

Sources

- NN (1999), "Domschulen", Lexikon des Mittelalters, vol. 3, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, p. columns 1226–1229

- Kottje, R. (1999), "Klosterschulen", Lexikon des Mittelalters, vol. 5, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, p. columns 1226–1228

- Riché, Pierre (1978), Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-376-8

External links

- [1]

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [2]