Puertasaurus

| Puertasaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous

| |

|---|---|

| |

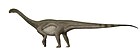

| Skeletal diagram with known material in white and unknown material restored in gray | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Lognkosauria |

| Genus: | †Puertasaurus Novas et al., 2005 |

| Type species | |

| Puertasaurus reuili Novas et al., 2005

| |

Puertasaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in South America during the Late Cretaceous Period. It is known from a single specimen recovered from sedimentary rocks of the Cerro Fortaleza Formation in southwestern Patagonia, Argentina, which probably is Campanian or Maastrichtian in age. The only species is Puertasaurus reuili. Described by the paleontologist Fernando Novas and colleagues in 2005, it was named in honor of Pablo Puerta and Santiago Reuil, who discovered and prepared the specimen. It consists of four well-preserved vertebrae, including one cervical, one dorsal, and two caudal vertebrae. Puertasaurus is a member of Titanosauria, the dominant group of sauropods during the Cretaceous.

Puertasaurus was a very large animal. Its size is difficult to estimate due of the scarcity of its remains, but current estimates place it around 30 meters (98 feet) long and 50 metric tons (55 short tons) in mass. The largest of the four preserved bones is the dorsal vertebra, which at 1.68 meters (5 ft 6 in) wide is the broadest known vertebra of any sauropod. The Cerro Fortaleza Formation is of uncertain age, due to the inconsistency of stratigraphic nomenclature in Patagonia. When Puertasaurus was alive, the Cerro Fortaleza Formation would have been a humid, forested landscape. Puertasaurus would have shared its habitat with other dinosaurs, including another large sauropod, Dreadnoughtus, in addition to other reptiles and fish.

Discovery and naming

The holotype and only known specimen of Puertasaurus reuili was discovered in the Santa Cruz Province of southern Patagonia, Argentina. The remains were recovered in Cerro Los Hornos, near the La Leona River, and were reported from the Cerro Fortaleza Formation (which, at the time, was referred to as the Pari Aike Formation).[1] The holotype was discovered in a grey sandstone lens that also preserved the carbonized remains of cycads and conifers. It was given the specimen number of MPM 10002, and consists of four disarticulated vertebrae, specifically one cervical, one dorsal, and two caudal vertebrae (about 3% of the skeleton).[2] Of this material, only the dorsal vertebra was complete. Most of the cervical vertebra was preserved, but only the centra of the caudal vertebrae are known. Puertasaurus reuilli was described by the paleontologists Fernando Novas, Leonardo Salgado, Jorge Calvo, and Federico Agnolin in 2005, and was named after the fossil hunters Pablo Puerta and Santiago Reuil, who discovered the holotype in January 2001 and prepared it afterwards. Its discovery was announced in July 2006, at the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences in Buenos Aires.[3] Puertasaurus was the first discovered giant titanosaur that preserved cervical vertebrae.[4]

Description

Due to a lack of better material, the size of Puertasaurus is difficult to estimate.[5] Novas estimated the new species was approximately 35 to 40 meters (115 to 131 ft) long and weighing between 80 and 100 metric tons (88 and 110 short tons).[3] This would place it as one of the largest dinosaurs, only rivaled in size by its relative Argentinosaurus, which has been estimated at up to 39.7 meters (130 ft) in length and 90 metric tons (99 short tons) in mass.[6][7] The discovery of the more complete Futalognkosaurus revealed these previous estimates were likely too high.[8] In 2012, Thomas Holtz estimated Puertasaurus to have been potentially 30 meters (98 feet) long and 72.5-80 tonnes (80-88 short tons).[9][10] In 2013, the entire neck was estimated to have been approximately 9 meters (30 feet) long by Mike Taylor and Matt Wedel.[11] Later the same year, Scott Hartman made a reconstruction that suggests a total length of 27 meters (89 feet), slightly shorter than other estimates.[12] In 2016, Gregory S. Paul estimated a length of 30 meters (98 feet) and a weight of at least 50 metric tons (55 short tons).[13] In 2017, paleontologist José Carballido and his colleagues estimated its mass at roughly 60 metric tons (66 short tons), which was lighter than Patagotitan, a more complete giant sauropod.[14] In 2019, Gregory S. Paul estimated the mass of Puertasaurus to be in the size range of Patagotitan at 45–55 tonnes (50–61 short tons).[15]

Vertebrae

Of the four vertebrae preserved in the holotype, the largest is the dorsal vertebra (thought to be a second dorsal vertebra), measuring 1.06 meters (3 ft 6 in) tall and 1.68 meters (5 ft 6 in) wide. This is the broadest sauropod vertebra known, and two-thirds of its width is made up of the huge transverse processes (structures projecting from the side of the vertebra), which are heavily expanded and have very deep bases, forming wing-like structures when viewed from the front. In other titanosaurs, such as Dreadnoughtus, they are far less wide and deep.[16] In Puertasaurus, these processes are perpendicular to the axial plane. Craniocaudally (front to back), however, the vertebra is rather short, shorter than average among titanosaurs. The centrum is especially opisthocoelous (having a convex front and a concave rear). The laminae in the neural arch are robust, although reduced. Hyposphene-hypantrum articulation (two structures on two vertebrae that fit into each other and form an extra joint) is not present, like other titanosaurs. The pre- and postspinal fossae are especially deep and broad. The pre- and postspinal laminae (structures on the upper half of the vertebra) are robust. The neural spine is oriented vertically (perpendicular to the centrum) but dorsoventrally (top to bottom) low, although it is extremely transversely (side to side) expanded. This orientation is unlike that of more derived titanosaurs, instead it is similar to basal ones (such as Argentinosaurus) and other sauropods, such as Euhelopus.[4]

The cervical vertebra was also notably large, with a transverse width of 140 centimeters (55 inches) (including the cervical ribs). It is thought to be the ninth vertebra in the neck. The cervical ribs are fused to the centrum. The centrum is especially dorsoventrally compressed. The pre- and postspinal fossae on the neural spine are wide and deep. This, along with the expanded distal (front) end of the vertebra, provide evidence of powerful neck ligaments and muscles. These features are also known in other titanosaurs but are extremely prominent in Puertasaurus. The neural spine was especially tall and laterally (sideways) expanded, to the point where it would exceed the length of the centrum. This would make it have one of the proportionately largest neural spines of any titanosaur. The apex of the neural spine was positioned on the posterior side of the vertebral midline.[16] The spinoprezygapophyseal laminae (the spike-like projection in front of the neural spine) are separated from each other and only touch the middle of the neural spine.[17] The zygapophyseal articulations, which connect two adjacent vertebrae, are located on the lower part the neural arch. The diapophyses and parapophyses (processes on the side of the vertebra) are strongly laterally projected. The cervical vertebra lacks pleurocoels (large cavities) and was not very pneumatic. The length of the restored centrum is estimated to be 105 centimeters (41 inches) long based on other titanosaurs.[4]

Two caudal vertebrae from the middle of the tail were also preserved. They are standard in shape for titanosaurs and are procoelous (having a concave front and a convex rear).[4] Little else is known about them since they were never described in detail.[18]

Classification

Puertasaurus is differentiated from other sauropods based on a unique combination of features. These features consist of the heavily expanded neural spines on the cervical vertebrae, which result in the neural spines being longer than the vertebral body. The neural spines possess strong dorsolateral (high on the side) ridges, robust spinoprezygapophyseal laminae (projections in front of the neural spine) of the posterior cervicals, anterior dorsals that are very short from front to back, and the animal's giant size.[4]

Puertasaurus belonged to the clade Titanosauria, one of the most diverse groups of sauropods. It is a member of the group Lognkosauria, which includes several other large titanosaurs, including Futalognkosaurus, Patagotitan, Argentinosaurus, Notocolossus, Mendozasaurus, and Quetecsaurus. Many of these animals, such as Argentinosaurus and Patagotitan, were especially massive. Puertasaurus is generally recovered as a stable (a firm member of the group) lognkosaur, although in 2017, Carballido found it (along with Quetecsaurus) to be the least stable members of the group.[2][14][19]

The following cladogram shows the position of Puertasaurus in Lognkosauria according to Gonzalez Riga and colleagues, 2018.[19]

Paleoecology

Puertasaurus is from the Late Cretaceous Period of southern Patagonia. However, which formation it was derived from and its geological age have been disputed, because of the inconsistent stratigraphic nomenclature of southern Patagonia. It was originally reported as being from the Pari Aike Formation, and Maastrichtian in age. The Pari Aike Formation was subsequently reassigned to the Mata Amarilla Formation and reinterpreted as being from the Cenomanian to Santonian.[20] More recent studies have stated that these deposits pertain to the Cerro Fortaleza Formation, which was dated to the Campanian or Maastrichtian.[16] The rocks of the formation mostly consist of sandstone beds, along with layers of mudstone and lignitic horizons.[1]

The Cerro Fortaleza Formation represents a terrestrial ecosystem. The presence of paleosols and lignite suggests a humid environment with high amounts of rainfall and a high water table. Avulsion surfaces, histosols, carbonaceous fossil roots, and silicified wood all provide evidence of a low-lying forested landscape with poor drainage.[4] Other dinosaurs from the same locality include the ornithopod Talenkauen, the theropods Orkoraptor and Austrocheirus, and the sauropod Dreadnoughtus.[16][21][22] Non-dinosaurian fauna known from the formation include crocodilians, turtles, bony fish, and lamniform sharks.[1][23][24]

References

- ^ a b c Schroeter, E.R.; Egerton, V.M.; Ibiricu, L.M.; Lacovara, K.J. (2014). "Lamniform Shark Teeth from the Late Cretaceous of Southernmost South America (Santa Cruz Province, Argentina)". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e104800. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j4800S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104800. PMC 4139311. PMID 25141301.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Calvo, J. O.; Porfiri, J. D.; González Riga, B. J.; Kellner, A. W. A. (2007). "Anatomy of Futalognkosaurus dukei Calvo, Porfiri, González Riga, & Kellner, 2007 (Dinosauria, Titanosauridae) from the Neuquen Group, Late Cretaceous, Patagonia, Argentina" (PDF). Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 65 (4): 511–526. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Roach, J. (2006). "Giant Dinosaur Discovered in Argentina". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on August 11, 2006. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Novas, Fernando E.; Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge; Agnolin, Federico (2005). "Giant titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia" (PDF). Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. N.S. 7 (1): 37–41. doi:10.22179/REVMACN.7.344. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2006. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ Hartman, Scott (June 20, 2013). "The Problem With Puertasaurus". Skeletal Drawing. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Sellers, W. I.; Margetts, L.; Coria, R. A. B.; Manning, P. L. (2013). Carrier, David (ed.). "March of the Titans: The Locomotor Capabilities of Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e78733. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878733S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078733. PMC 3864407. PMID 24348896.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Benson, Roger B. J.; Campione, Nicolás E.; Carrano, Matthew T.; Mannion, Phillip D.; Sullivan, Corwin; Upchurch, Paul; Evans, David C. (May 6, 2014). "Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage". PLOS Biology. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Calvo, Jorge O.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén D.; Porfiri, Juan D. (2008). "Re-sizing giants: estimation of body lenght [sic] of Futalognkosaurus dukei and implications for giant titanosaurian sauropods". Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología de Vertebrados. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Holtz, Tom (2012) Genus List for Holtz (2007) Dinosaurs

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Taylor, M.P.; Wedel, M.J. (2013). "Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks". PeerJ. 1: e36. doi:10.7717/peerj.36. PMC 3628838. PMID 23638372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hartman, Scott (2013). "The biggest of the big". Skeletal Drawing. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (2016) The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. 2nd ed. Princeton University Press p. 206

- ^ a b Carballido, José L.; et al. (2017). "A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs". Proc. R. Soc. B. 284 (1860): 20171219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1219. PMC 5563814. PMID 28794222.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2019). "Determining the largest known land animal: A critical comparison of differing methods for restoring the volume and mass of extinct animals" (PDF). Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 335–358.

- ^ a b c d Lacovara, Kenneth J.; Ibiricu, L.M.; Lamanna, M.C.; Poole, J.C.; Schroeter, E.R.; Ullmann, P.V.; Voegele, K.K.; Boles, Z.M.; Egerton, V.M.; Harris, J.D.; Martínez, R.D.; Novas, F.E. (September 4, 2014). "A Gigantic, Exceptionally Complete Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur from Southern Patagonia, Argentina". Scientific Reports. 4: 6196. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E6196L. doi:10.1038/srep06196. PMC 5385829. PMID 25186586.

- ^ González Riga, Bernardo J.; David, Leonardo Ortiz (2014). "A new titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous (Cerro Lisandro Formation) of Mendoza Province, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 51 (1): 3–25. doi:10.5710/AMEGH.26.12.1013.1889.

- ^ Fowler, Denver W.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2011). "The first giant titanosaurian sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 685–690. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0105.

- ^ a b Gonzalez Riga, B.J.; Mannion, P.D.; Poropat, S.F.; Ortiz David, L.; Coria, J.P. (2018). "Osteology of the Late Cretaceous Argentinean sauropod dinosaur Mendozasaurus neguyelap: implications for basal titanosaur relationships". Journal of the Linnean Society. 184 (1): 136–181. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx103. hdl:10044/1/53967.

- ^ Varela, Augusto N.; Poiré, Daniel G.; Martin, Thomas; Gerdes, Axel; Goin, Francisco J.; Gelfo, Javier N.; Hoffmann, Simone (2012). "U-Pb zircon constraints on the age of the Cretaceous Mata Amarilla Formation, Southern Patagonia, Argentina: its relationship with the evolution of the Austral Basin". Andean Geology. 39 (3): 359–379. doi:10.5027/andgeoV39n3-a01.

- ^ Novas, Fernando E.; Martín D. Ezcurra; Agustina Lecuona (2008). "Orkoraptor burkei nov. gen. et sp., a large theropod from the Maastrichtian Pari Aike Formation, Southern Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 29 (3): 468–480. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.01.001.

- ^ Ezcurra, M.D.; Agnolin, F.L.; Novas, F.E. (2010). "An abelisauroid dinosaur with a non-atrophied manus from the Late Cretaceous Pari Aike Formation of southern Patagonia" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2450: 1–25. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2450.1.1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Novas, Fernando E.; Cambiaso, Andrea V; Ambrioso, Alfredo (2004). "A new basal iguanodontian (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia". Ameghiniana. 41 (1): 75–82.

- ^ Goin, Francisco J.; et al. (2002). "Paleontología y Geología de los sedimentos del Cretácico Superior aflorantes al sur del río Shehuen (Mata Amarilla, Provincia de Santa Cruz, Argentina)". Actas del XV Congreso Geológico Argentino. 1.

External links

Media related to Puertasaurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Puertasaurus at Wikimedia Commons