Francesca da Rimini

Francesca da Rimini (Italian pronunciation: [franˈtʃeska da (r)ˈriːmini]) or Francesca da Polenta (IPA: [franˈtʃeska da (p)poˈlɛnta]);[1][2] 1255 – c. 1285) was the daughter of Guido da Polenta, lord of Ravenna. She was a historical contemporary of Dante Alighieri, who portrayed her as a character in the Divine Comedy.

Life and death

Daughter of Guido I da Polenta of Ravenna, Francesca was wedded in or around 1275 to the brave, yet crippled Giovanni Malatesta (also called Gianciotto or "Giovanni the Lame"), son of Malatesta da Verucchio, lord of Rimini.[3] The marriage was a political one; Guido had been at war with the Malatesta family, and the marriage of his daughter to Giovanni was a way to secure the peace that had been negotiated between the Malatesta and the Polenta families. While in Rimini, she fell in love with Giovanni's younger brother, Paolo. Though Paolo, too, was married, they managed to carry on an affair for some ten years, until Giovanni ultimately surprised them in Francesca's bedroom some time between 1283 and 1286, killing them both.[4][5]

In Inferno

In the first volume of The Divine Comedy, Dante and Virgil meet Francesca and her lover Paolo in the second circle of hell, reserved for the lustful. Here, the couple are trapped in an eternal whirlwind, doomed to be forever swept through the air just as they allowed themselves to be swept away by their passions. Dante calls out to the lovers, who are compelled briefly to pause before him, and he speaks with Francesca. She obliquely states a few of the details of her life and her death, and Dante, apparently familiar with her story, correctly identifies her by name. He asks her what led to her and Paolo's damnation, and Francesca's story strikes such a chord within Dante that he faints out of pity.

- Works of art inspired by the Inferno scene

-

Henry Fuseli: Dante Observing the Soaring Souls of Paolo and Francesca, pen and ink, c. 1800

-

Joseph Anton Koch: Dante and Virgil in the Second Circle in Hell, pen, ink and watercolor on paper, 1823

-

Giuseppe Fraschieri: Dante e Virgilio incontrano Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, 1846 (Civica Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Savona)

-

Joseph Noel Paton: Dante Meditating the Episode of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, oil on canvas, 1852 (Bury Art Museum)

-

Gustave Doré: The Souls of Paolo and Francesca, etching, 1857

-

Gustave Doré: The Souls of Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1863

-

George Frederic Watts: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1875 (Watts Gallery, Surrey)

-

Mosè Bianchi: Paolo and Francesca, watercolor and gold on paper, c. 1877 (Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan)

-

Henri-Jean Guillaume Martin: Paolo Malatesta et Francesca da Rimini aux enfers, oil on canvas, 1883 (Musée des beaux-arts, Carcassonne)

-

Auguste Rodin: Paolo et Francesca, or Couple damné (Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon)

-

Eugène Deully: Dante et Virgile aux Enfers, 1897

-

Amelia Bauerle: Paolo and Francesca, 1902

-

Umberto Boccioni: Il sogno, or Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, 1909 (Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna, Ferrara)

-

Gaetano Previati: Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, 1909

-

John Riley Wilmer: Paolo and Francesca, watercolor, gouache and ink, 1930

Reception after Dante

In the years following Dante's portrayal of Francesca, legends about Francesca began to appear. Chief among them was one put forth by poet Giovanni Boccaccio in his commentary on The Divine Comedy, Esposizioni sopra la Comedia di Dante; he stated that Francesca had been tricked into marrying Giovanni through the use of Paolo as a proxy. Guido, fearing that Francesca would never agree to marry the crippled Giovanni, had supposedly sent for the much more handsome Paolo in Giovanni's stead. It wasn't until the morning after the wedding that Francesca discovered the deception. This version of events, however, is very likely a fabrication. It would have been nearly impossible for Francesca not to know who both Giovanni and Paolo were, and that Paolo was already married, given the dealings the brothers had had with Ravenna and Francesca's family. Also, Boccaccio was born in 1313, some 27 years after Francesca's death, and while many Dante commentators after Boccaccio echoed his version of events, none before him had mentioned anything similar.[6]

In the 19th century, the story of Paolo and Francesca inspired numerous theatrical, operatic, and symphonic adaptations.

Related works

Poetry

- Dante, Divine Comedy – Inferno, Canto V, lines 73–142 (1308–1321)

- Leigh Hunt, The Story of Rimini (1816)

Theatre and opera

- Silvio Pellico, Francesca da Rimini, tragedy (1818)

- Feliciano Strepponi, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Padua 1823)

- Luigi Carlini, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Naples 1825)

- Saverio Mercadante, Francesca da Rimini, opera (Madrid 1831)

- Pietro Generali, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Paolo Pola (Venice 1828)

- Gaetano Quilici, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Lucca 1829)

- Giuseppe Staffa, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Naples 1831)

- Giuseppe Fournier-Gorre, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Livorno 1832)

- Giuseppe Tamburini, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Rimini 1835)

- Francesco Morlacchi, Francesca da Rimini, opera (composed for Venice 1836, but unperformed)

- Emanuele Borgatta, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Genoa 1837)

- Gioacchino Maglioni, Francesca da Rimini, opera (Genoa 1840)

- Eugen Nordal (pseudonym of Johann Arnold-Gruber), Francesca da Rimini, opera after Paolo Pola (Linz 1840; performed posthumously)

- Salvatore Papparlado, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts (Genoa 1840; unperformed)

- Francesco Cannetti, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Felice Romani (Vicenza 1843)

- Vincenzo Sassaroli, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Felice Romani (Catania 1846)

- George Henry Boker, Francesca da Rimini, play (1853)

- Giovanni Franchini, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Lisbon 1857)

- Jan Neruda, Francesca di Rimini, play (1860)

- Giuseppe Marcarini, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Benvenuti (Piacenza 1870)

- Hermann Goetz, Francesca von Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by the composer (Mannheim 1877; overture and act III completed by Ernst Frank)

- Antonio Cagnoni, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts, libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni (Turin 1878)

- Gabriele D'Annunzio, Francesca da Rimini, tragedy (1901; written for D'Annunzio's mistress, Eleonora Duse)

- Ambroise Thomas, Françoise de Rimini, opera (Paris 1882)

- Antonio Scontrino, Francesca da Rimini, "tragedia" (in fact an opera) in five acts, libretto after D'Annunzio (Rome 1901)

- Stephen Phillips, Paolo and Francesca, play (1902)[7]

- Francis Marion Crawford, Francesca da Rimini, play in five acts (1902)

- Marcel Schwob, Francesca da Rimini, play, translation of Crawford (given with music by Gabriel Pierné Paris 1902, Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt)

- Eduard Nápravník, Francesca da Rimini, opera (St. Petersburg 1902)

- Sergei Rachmaninoff, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts, libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky (Moscow 1906)

- Luigi Mancinelli, Paolo e Francesca, opera in one act (1907)[8]

- Emil Ábrányi, Paolo és Francesca, opera in three acts, libretto after Dante by Emil Ábrányi, Sr. (Budapest 1912)

- Franco Leoni, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three tableaux, based on Crawford's play (Paris 1914, Opéra-Comique)

- Primo Riccitelli, Francesca da Rimini, opera

- Riccardo Zandonai, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts, libretto by Tito Ricordi, based on D'Annunzio (Turin 1914)

- Nino Berrini, Francesca da Rimini, play (1924)

Music

- Gioachino Rossini, "Farò come colui che piange e dice", aria (musical setting of Inferno, Canto 5, lines 126ff., 1848)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Francesca da Rimini, symphonic poem (1876)

- Arthur Foote, Symphonic Prologue Francesca da Rimini, Op. 24 (1890)

- Antonio Bazzini, Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Poem, Op. 77 (Berlin 1890)

- Pierre Maurice, Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Poem, Op. 6 (1899)

- Paul von Klenau, Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Poem (1913, revised 1919)

- Olga Gorelli, Paolo e Francesca, guitar duo from the album Hausmusik. 20th Century Chamber Music for the Home (2000)

- Mediæval Bæbes, "The Circle of the Lustful" from The Rose album (2002)

- Saverio Mercadante, "Francesca da Rimini" Opera 1830-31

Film

- Paolo e Francesca, 1950 film by Raffaello Matarazzo

Art

- Joseph Anton Koch, Paolo and Francesca Surprised by Gianciotto, watercolor (1805; Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen)

- Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie, The Tragic Love of Francesca da Rimini, oil on canvas (1812; Napoleonmuseum, Arenberg)

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas (1819;Musée des Beaux-Arts, Angers, France)

- Ary Scheffer, Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta Appraised by Dante and Virgil, oil on canvas (1835; Wallace Collection, London; an 1855 version is in the Louvre, Paris), and there are other versions

- Gustave Doré, Francesca da Rimini, several illustrations to Dante's Inferno (1857)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1862)

- Alexandre Cabanel, The Death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, oil on canvas (1870; Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

- George Frederic Watts, Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas (between 1872 and 1884; private collection)

- Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, marble sculpture (1888; Musée Rodin, Paris)

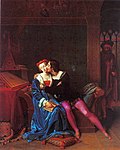

- The tête-à-tête

-

William Dyce: Francesca da Rimini, oil on canvas, 1837 (Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh)

-

Anselm Feuerbach: Paolo und Francesca, study, 1864 (Kunsthalle Mannheim)

-

Anselm Feuerbach: Paolo und Francesca, sketch, 1864

-

Anselm Feuerbach: Paolo und Francesca, oil on canvas, 1864 (Schackgalerie, Munich)

-

Amos Cassioli: Paolo e Francesca or Il Bacio, 1870

-

Charles Edward Hallé: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas

-

Ludwik Wiesiołowski: Francesca i Paolo, oil on canvas, 1885

-

Arnold Böcklin: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1893 (Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur)

-

Frank Dicksee: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1894

- The dagger scene and the lovers' death

-

Joseph Anton Koch: Paolo da Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini surprised by Gianciotto Malatesta, pen, ink and watercolor on paper, 1805 (Thorvaldsen Museum)

-

Bartolomeo Pinelli: La Franceschina di Rimini, c. 1809 (Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen)

-

Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie: The Tragic Love of Francesca da Rimini, 1812 (Napoleonmuseum, Arenenberg, Constance)

-

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: Gianciotto Discovers Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1819 (Musée Bonnat, Bayonne)

-

Eugène Delacroix: Paolo et Francesca, watercolor, 1825

-

Gustave Doré: Illustration of Inferno, Canto 5 (lines 134–135), 1857

-

Francisco Díaz Carreño: Francisca de Rímini, oil on canvas, 1866 (Prado, Madrid)

-

Gaetano Previati: Paolo e Francesca, or Morte di Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, c. 1887 (Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti di Bergamo)

References

Notes

- ^ Luciano Canepari. "Francesca". DiPI Online (in Italian). Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Luciano Canepari. "Polenta". DiPI Online (in Italian). Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2003). The Divine Comedy. New York: New American Library. p. 52. Translation and commentary by John Ciardi.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2000). The Inferno. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 106–107. Translation and commentary by Robert and Jean Hollander.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda (January 2000). "Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender". Speculum. 75 (1): 3. doi:10.2307/2887423. JSTOR 2887423.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda (January 2000). "Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender". Speculum. 75 (1): 16. doi:10.2307/2887423. JSTOR 2887423.

- ^ Produced by Sir George Alexander at the St James's Theatre beginning 6 March 1902. Mason, p. 237. See William Calin, "Dante on the Edwardian Stage: Stephen Phillips's Paolo and Francesca." In: Medievalism in the Modern World. Essays in Honour of Leslie J. Workman, ed. Richard Utz and Tom Shippey (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998), pp. 255–61.

- ^ Paolo e Francesca, opera by Luigi Mancinelli, booklet (synopsis, libretto), 2004 recording Naxos Records

General references

- Mason, A. E. W. (1935). Sir George Alexander & The St. James' Theatre. Reissued 1969, New York: Benjamin Blom.

- Hollander, Robert and Jean (2000). The Inferno. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-49698-2.

Further reading

- Singleton, Charles S. (1970). The Divine Comedy, Inferno/Commentary. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01895-2.

External links

- World of Dante, multimedia website that includes gallery of images of the Paolo and Francesca episode

- WisdomPortal, includes images of related artworks

- The Story of Rimini, Google Books edition of Leigh Hunt's poem

- Website of the Giornate Internazionali Francesca da Rimini at the Centro Internazionale di Studi Francesca da Rimini, Los Angeles (including one more image gallery)