Surfing

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|December 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Surfing is a surface water sport in which the participant is carried by a breaking wave on a surfboard. There are various kinds of surfing, based on the different methods or surf craft used to ride a wave. The basic categories include regular stand-up surfing, kneeboarding, bodyboarding, surf-skiing and bodysurfing. Further sub-divisions reflect differences in surfboard design, such as long-boards and short-boards. Tow-in surfing involves motorized craft to tow the surfer onto the wave. It is associated with surfing huge waves, which are extremely difficult to ride and sometimes impossible to catch by paddling down the face, due to their rapid forward motion.

Surfers and Surf Culture

Surfers represent a diverse culture that depends on the naturally occurring process of ocean waves. Some people practice surfing as a recreational activity while others demonstrate extreme devotion to the sport by making it the central focus of their lives.

The sport has become so popular that surfing now represents a multi-billion dollar industry. Some people make a career out of surfing by receiving corporate sponsorships, competing in contests, or marketing and selling surf related products, such as equipment and clothing. Other surfers separate themselves from any and all commercialism associated with surfing. These soul surfers, as they are often called, practice the sport purely for personal enjoyment and many even find a deeper meaning through involving themselves directly with naturally occurring wave patterns and subscribe to ecocentric philosophies, or ecosophies.

The Science of Surfing Waves

Several factors influence the shape and quality of breaking waves. These include the bathymetry of the surf break, the direction and size of the swell, the direction and strength of the wind and the ebb and flow of the tide.

Swell is generated when wind blows consistently over a large area of open water, called the wind's fetch. The size of a swell is determined by the strength of the wind, the length of its fetch and its duration. So, surf tends to be larger and more prevalent on coastlines exposed to large expanses of ocean traversed by intense low pressure systems.

Local wind conditions affect wave quality, since the rideable surface of a wave can become choppy in blustery conditions. Ideal surf conditions include a light to moderate strength "offshore" wind, since this blows into the front of the wave.

The factor which most determines wave shape is the topography of the seabed directly behind and immediately beneath the breaking wave. The contours of the reef or sand bank influence wave shape in two respects. Firstly, the steepness of the incline is proportional to the resulting upthrust. When a swell passes over a sudden steep slope, the force of the upthrust causes the top of the wave to be thrown forward, forming a curtain of water which plunges to the wave trough below. Secondly, the alignment of the contours relative to the swell direction determines the duration of the breaking process. When a swell runs along a slope, it continues to peel for as long as that configuration lasts. When swell wraps into a bay or around an island, the breaking wave gradually diminishes in size, as the wave front becomes stretched by diffraction. For specific surf spots, the state of the ocean tide can play a significant role in the quality of waves or hazards of surfing there. Tidal variations vary greatly among the various global surfing regions, and the effect the tide has on specific spots can vary greatly among the spots within each area. Locations such as Bali, Panama, and Ireland experience 2-3 meter tide fluctuations, whereas in Hawaii the difference between high and low tide is typically less than one meter.

In order to know a surf break, one must be sensitive to each of these factors. Each break is different, since the underwater topography of one place is unlike any other. At beach breaks, even the sandbanks change shape from week to week, so it takes commitment to get good waves (a skill dubbed "broceanography" by California surfers). That's why surfers have traditionally regarded surfing to be more of a lifestyle than a sport. Of course, you can sometimes be lucky and just turn up when the surf is pumping. But, it is more likely that you will be greeted with the dreaded: "You should have been here yesterday." Nowadays, however, surf forecasting is aided by advances in information technology, whereby mathematical modelling graphically depicts the size and direction of swells moving around the globe.

The regularity of swell varies across the globe and throughout the year. During winter, heavy swells are generated in the mid-latitudes, when the north and south polar fronts shift toward the Equator. The predominantly westerly winds generate swells that advance eastward. So, waves tend to be largest on west coasts during the winter months. However, an endless train of mid-latitude cyclones causes the isobars to become undulated, redirecting swells at regular intervals toward the tropics.

East coasts also receive heavy winter swells, when low pressure cells form in the sub-tropics, where their movement is inhibited by slow moving highs. These lows produce a shorter fetch than polar fronts, however they can still generate heavy swells, since their slower movement increases the duration of a particular wind direction. After all, the variables of fetch and duration both influence how long the wind acts over a wave as it travels, since a wave reaching the end of a fetch is effectively the same as the wind dying off.

During summer, heavy swells are generated when cyclones form in the tropics. Tropical cyclones form over warm seas, so their occurrence is influenced by El Niño & La Niña cycles. Their movements are unpredictable. They can even move westward, which is unique for a large scale weather system. In 1979, Tropical Cyclone Kerry wandered for 3 weeks across the Coral Sea and into Queensland, before dissipating.

The quest for perfect surf has given rise to a field of tourism based on the surfing adventure. Yacht charters and surf camps offer surfers access to the high quality surf found in remote, tropical locations, where tradewinds ensure offshore conditions. Since winter swells are generated by mid-latitude cyclones, their regularity coincides with the passage of these lows. So, the swells arrive in pulses, each lasting for a couple of days, with a couple of days between each swell. Since bigger waves break in a different configuration, a rising swell is yet another variable to consider when assessing how to approach a break.

Artificial Reefs

The value of good surf has even prompted the construction of artificial reefs and sand bars to attract surf tourism. Of course, there is always the risk that one's holiday coincides with a "flat spell". Wave pools aim to solve that problem, by controlling all the elements that go into creating perfect surf, however there are only a handful of wave pools that can simulate good surfing waves, owing primarily to construction and operation costs and potential liability.

To learn more about surf meteorology, see StormSurf's Tutorials.

The availability of free model data from the NOAA has allowed the creation of several surf forecasting websites. These automatically combine the above variables into a presentation of how good the surf will be.

Wave intensity classification

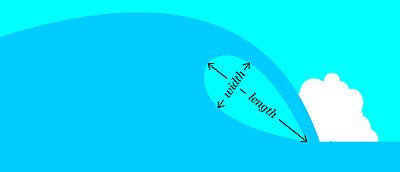

Surf breaks can be grouped according to their intensity. There are two variables to consider in determining the intensity of a surf break: the shape of the tube and the angle of the peel line. Tube shape indicates the degree of upthrust, which is roughly proportional to the volume of water being thrown over with the lip. The angle of the peel line reflects the speed of the tube. A fast, "down the line" tube has a peel line with a smaller angle than a slower, "bowly" tube.

Classification parameters

- Tube shape defined by length to width ratio

- Square: <1:1

- Round: 1-2:1

- Almond: >2:1

- Tube speed defined by angle of peel line

- Fast: 30°

- Medium: 45°

- Slow: 60°

| Fast | Medium | Slow | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Square | The Cobra | Teahupoo | Shark Island |

| Round | Speedies, Gnaraloo | Banzai Pipeline | |

| Almond | Lagundri Bay, Superbank | Jeffreys Bay, Bells Beach | Angourie Point |

Surfing maneuvers

Surfing begins with the surfer eyeing a rideable wave on the horizon and then matching its speed (by paddling or sometimes, in huge waves, by tow-in). A common problem for beginners is not even being able to catch the wave in the first place, and one sign of a good surfer is being able to catch a difficult wave that other surfers can not.

Once the wave has started to carry the surfer forward, the surfer will then quickly jump to his or her feet and proceeds to ride down the face of the wave, generally staying just ahead of the breaking part (white water) of the wave (in a place often referred to as "the pocket" or "the curl"). This is a difficult process in total, where often everything happens nearly simultaneously, making it hard for the uninitiated to follow the steps.

Surfers' skills are tested not only in their ability to control their board in challenging conditions and/or catch and ride challenging waves, but also by their ability to execute various maneuvers such as turning and carving. Some of the common turns have become recognizable tricks such as the "cutback" (turning back toward the breaking part of the wave), the "floater" (riding on the top of the breaking curl of the wave), and "off the lip" (banking off the top of the wave). A newer addition to surfing has been the progression of the "air" where a surfer is able to propel oneself off the wave and re-enter.

"Tube riding" is when a surfer maneuvers into a position where the wave curls over the top of him or her, forming a "tube" (or "barrel"), with the rider inside the hollow cylindrical portion of the wave. This difficult and sometimes dangerous procedure is arguably the most coveted and sought after goal in surfing.

"Hanging Ten" and "Hanging Five" are moves usually specific to longboarding. Hanging Ten refers to having both feet on the front end of the board with all ten of the surfer's toes off the edge, also known as noseriding. Hanging Five is having just one foot near the front, and five toes off the edge.

Common Terms:

- Regular foot - Right foot on back of board

- Goofy foot - Left foot on back of board

- Take off - the start of a ride

- Drop in - dropping into (engaging) the wave, most often as part of standing up

- Drop in on (or "cut off") - taking off on a wave in front of someone else (considered inappropriate)

- Snaking - paddling around someone to get into the best position for a wave (in essence, stealing it)

- Bottom turn - the first turn at the bottom of the wave

- Shoulder - the unbroken part of the wave

- Cutback - a turn cutting back toward the breaking part of the wave

- Fade - on take off, aiming toward the breaking part of the wave, before turning sharply and surfing in the direction the wave is breaking towards

- Over the falls - out of control, going over the front of the wave and wiping out

- Pump - an up/down carving movement that generates speed along a wave

- Stall - slowing down from weight on the tail of the board or a hand in the water

- Floater - riding up on the top of the breaking part of the wave

- Hang-five/hang-ten - putting five or ten toes respectively over the nose of a longboard

- Re-entry - hitting the lip vertically and re-rentering the wave in quick succession.

- Switch-foot - having equal ability to surf regular foot or goofy foot -- like being ambidextrous

- Tube riding - riding inside the curl of a wave

- Carve - turns (often accentuated)

- Off the Top - a turn on the top of a wave, either sharp or carving

- Snap - a quick, sharp turn off the top of a wave

- Fins-free snap - a sharp turn where the fins slide off the top of the wave

- Air/Aerial - riding the board briefly into the air above the wave, landing back upon the wave, and continuing to ride.

Surfing equipment

Surfing can be done on various pieces of equipment, including surfboards, bodyboards, wave skis, kneeboards and surf mat. Surfboards were originally made of solid wood and were generally quite large and heavy (often up to 12 feet long and 100 pounds / 45 kg). Lighter balsa wood surfboards (first made in the late 1940s and early 1950s) were a significant improvement, not only in portability, but also in increasing maneuverability on the wave.

Most modern surfboards are made of polyurethane foam (with one or more wooden strips or "stringers"), fiberglass cloth, and polyester resin. An emerging surf technology is an epoxy surfboard, which are stronger and lighter than traditional fiberglass.

Equipment used in surfing includes a leash (to keep a surfer's board from washing to shore after a "wipeout", and to prevent it from hitting other surfers), surf wax and/or traction pads (to keep a surfers feet from slipping off the deck of the board), and "fins" (also known as "skegs") which can either be permanently attached ("glassed-on") or interchangeable. In warmer climates swimsuits, surf trunks or boardshorts are worn, and occasionally rash guards; in cold water surfers can opt to wear wetsuits, boots, hoods, and gloves to protect them against lower water temperatures.

There are many different surfboard sizes, shapes, and designs in use today. Modern longboards, generally 9 to 10 feet in length, are reminiscent of the earliest surfboards, but now benefit from all the modern innovations of surfboard shaping and fin design.

The modern shortboard began its life in the late 1960s evolving up to today's common "thruster" style shortboard, a three fin design, usually around 6 to 7 feet in length.

Midsize boards, often called funboards, provide more maneuverability than a longboard, with more floatation than a shortboard. While many surfers find that funboards live up to their name, providing the best of both surfing modes, others are critical. "It is the happy medium of mediocrity," writes Steven Kotler. "Funboard riders either have nothing left to prove or lack the skills to prove anything." [1]

There are also various niche styles, such as the "Egg", a longboard-style short board, the "Fish", a short and wide board with a split tail and two or four fins, and the "Gun", a long and pointed board specifically designed for big waves.

Surfing dangers

Surfing, like all water sports, has the obvious inherent danger of drowning, however this danger can be higher than in other water sports. When surfing, a surfer should not assume that they will always have their board to keep them buoyant - the leg rope could break or fall off some other way, and the board could become separated from the surfer by unpredictable wave crashes. A surfer needs to be confident that he/she can safely swim back to the beach unaided without his/her board. However, even if a surfer is confident in their swimming ability, there is always the possibility that the surfer could become unconscious through a head collision with another surfer, their own board, or rocks, reefs, or hard sand on the bottom of the water, in which case they won't be able to swim at all. This is why it's also important to surf with others you know, or at least have someone watching out for you from the beach.

Sharks are also a danger for surfers, with attacks reported from surfers every year.

Surf rage can be a problem in places where there are limited surfing breaks and many surfers trying to ride the breaks. This can be especially true if some unspoken agreement between the surfers about whose turn it is to take the break is not understood by one or more surfers, which can often be the case due to the informal and unspoken nature of this agreement.

Famous surf breaks

Some of the best known surf breaks:

- See also: List of surfing areas

Notable surfers

All-time top female surfers (not necessarily in contests)

- Rochelle Ballard

- Layne Beachley

- Lynne Boyer

- Bethany Hamilton

- Joyce Hoffman

- Keala Kennelly

- Sofia Mulanovich

- Margo Oberg

- Jericho Poppler

- Cori Schumacher

- Rell Sunn

- Freida Zamba

2005 World Tour Top 10

- Kelly Slater (USA) 7962 (World Champion: 1992, 1994-98, 2005-06)

- Andy Irons (Haw) 7860 (World Champion: 2002-04)

- Mick Fanning (Aus) 6650

- Damien Hobgood (USA) 6148

- Phillip MacDonald (Aus) 6060

- Trent Munro (Aus) 5748

- Taj Burrow (Aus) 5512

- Nathan Hedge (Aus) 5426

- CJ Hobgood (USA) 5248 (World Champion: 2001)

Previous world champions

- Midget Farrelly (Aus) (1964)

- Felipe Pomar (Peru)(1965)

- Nat Young (Aus) (1966)

- Fred Hemmings (Haw) (1968)

- Rolf Aurness (USA) (1970)

- James Blears (1972)

IPS tour

- Peter Townend (Aus) (1976)

- Shaun Tomson (SA) (1977)

- Wayne Bartholomew (Aus) (1978)

- Mark Richards (Aus) (1979-82)

ASP tour

- Tom Carroll (Aus) (1983, 84)

- Tom Curren (USA) (1985, 86,90)

- Damien Hardman (Aus) (1987,91)

- Barton Lynch (Aus) (1988)

- Martin Potter (SA) (1989)

- Derek Ho (Haw) (1993)

- Mark Occhilupo (Aus) (1999)

- Sunny Garcia (Haw) (2000)

Outside the contest context

- Miki Dora (USA)

- Gerry Lopez (Haw)

- Wayne Lynch (Aus)

- David Nuuhiwa (USA)

- Eddie Aikau (Haw)

- Bill Bragg (USA)

- Laird Hamilton (Haw)

- Rob Machado (Aus)

- Alan Stokes (GB)

References

- ^ West of Jesus, Surfing, Science and the Origins of Belief. Steven Kotler (2006).

See also

- History of surfing

- Surf forecasting

- World surfing champion

- ASP World Tour

- Surf culture

- Surf music

- River surfing

- Surf lifesaving, SLSC and nippers

- List of surfing topics

- List of surfing areas

- List of surfers

- Ecosystem

- Oceanography

- Ocean wave