Round Oak rail accident

| Round Oak rail accident | |

|---|---|

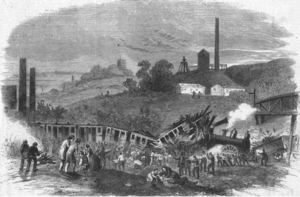

1858 print of 'The Accident on the Oxford and Worcester Railway, near Round Oak Station' | |

| Details | |

| Date | 23 August 1858 |

| Location | Round Oak, near Dudley |

| Coordinates | 52°28′59″N 2°07′39″W / 52.4830°N 2.1276°W |

| Country | England |

| Line | Oxford-Worcester-Wolverhampton Line |

| Cause | Train divided |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | 450 |

| Deaths | 14 |

| Injured | 50 |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

The Round Oak railway accident happened on 23 August 1858 between Brettell Lane and Round Oak railway stations, on the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway. The breakage of a defective coupling caused seventeen coaches and one brake van, containing about 450 passengers, of an excursion train to run backwards down the steep gradient between the stations, colliding with a following second portion of the excursion. 14 passengers were killed and 50 injured in the disaster. In the words of the Board of Trade accident inspector, Captain H. W. Tyler, it was at the time "decidedly the worst railway accident that has ever occurred in this country".

Circumstances of the accident

On 23 August 1858 the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway ran a special day excursion from Wolverhampton to Worcester and back. It was intended to be for school children and their teachers only, but this ruling was not adhered to and the train was packed with roughly equal numbers (about 750 of each) of children and adults. The train left Wolverhampton at 9.12 AM, comprising 42 four-wheeled coaches and four brake vans. Braking of the train was supplied entirely by manual application of brakes on the engine (and tender) and the four brake vans (each van manned by a guard).[a]

Guard Cooke was in the rear brake van of the train, together with six passengers, who should not have been there. Cooke and his passengers were drinking and smoking in the van, and Cooke invited passengers to apply the van handbrake.[1] Correct operation of the brake was necessary, not only to slow the train, but also to control the tension in the carriage couplings. There were three separate breakages of couplings ahead of the rear brake van on the outward journey: at Brettell Lane and Hagley both the main screw couplings and side safety chains failed, and at Droitwich it was found that another screw coupling was failed, but its associated side chains had held. Cooke made temporary repairs on all three occasions. To repair the first two breakages, Cooke managed to find spare three-link or screw couplings; but at Droitwich he was only able to patch up the side chains, which were not designed to hold the full weight of a train. On arrival at Worcester, the train was examined by the inspector of rolling stock: the repaired/replaced side chains were replaced by four-link goods couplings before the return journey, but no attempt was made to repair or replace failed centre couplings: these were difficult to access, and the inspector considered that a re-made screw coupling was weaker than the goods couplings (which he considered adequate).

The accident

On the return journey, the excursion train was divided into two portions: the first, with Guard Cooke in the rear brake van, comprised 28 coaches and two brake vans pulled by one locomotive as far as Stourbridge where a second locomotive was attached; and the second comprised 14 coaches and two brake vans, hauled by one locomotive. There was a 1 in 75 rising gradient between Brettell Lane and Round Oak, and the line was worked on the interval system, in which trains were allowed to follow the previous train without positive confirmation that it had reached the next station, relying instead on it having been an adequate (specified) time interval ahead at the last station. The first train reached Round Oak at about 8.10 pm; as it drew to a halt a foreman-platelayer heard a loud 'snap' as the coupling behind the eleventh coach broke and 17 coaches and the rear brake van began to roll back down the incline towards Brettell Lane. The booking clerk at Round Oak, seeing the runaway, attempted to telegraph Brettell Lane to give warning, but he was unable to attract the attention of the clerk there. The second train had reached Brettell Lane about eleven or twelve minutes behind the first, and therefore was clear to proceed to Round Oak. The line ran in a series of curves, limiting forward visibility, the night was dark, there were no lights in the coaches, excursion trains did not have to have a red light on the rearmost vehicle,[2] and smoke was blowing across the line from neighbouring factories; consequently the crew of the second train did not see the runaway coaches until they were about 300 yards away. The second train had virtually drawn to a standstill when the runaway coaches collided with it. The locomotive of the second train remained on the rails and was only superficially damaged; the same was not true of the runaway coaches. Cooke's brakevan and the two coaches next to it were, in the words of the inspector "broken all to pieces", killing 14 passengers and badly injuring 50 more.

The investigation

The accident was investigated by Captain Tyler of the Railway Inspectorate; there was also a coroner's inquest on those who had died in the crash. [b] Tyler showed by experiment that when a string of carriages matching the runaway train section was allowed to run back down the incline for quarter of a mile before the brake was applied, application of the brake then brought the carriages to rest well before the site of the collision. Furthermore, he considered that the severity of damage showed that no braking at all had been applied to the runaway. The brakescrew on the runaway brake van had been bent in the collision, and the nut was at the bottom of the working section of the screw, indicating that the brake had been off at the time of collision.

Tyler therefore rejected Cooke's evidence that he had applied the brake as the train was arriving at Round Oak; the coupling had failed when he released the brake, but he had reapplied the brake on becoming aware of the breakaway; this had initially had some effect, but the runaway had then skidded down the incline with gathering speed.[c] Instead, Tyler thought, Cooke had left the brake van as it arrived at Round Oak, without applying the brake, an obviously necessary precaution against a 'rebound of the buffers' (a shock loading on couplings as coaches hit and bounced back from the coach ahead): consequently a screw coupling had failed (the failed coupling had a grossly defective weld, as did many of the couplings examined on other coaches in the train) and the side chains had in their turn been unable to resist the shock loading. Cooke, thought Tyler, had been unable to regain the brakevan as the portion of the train to the rear of the failed coupling ran away but had either travelled down on the runaway or run after it sufficiently fast to reach the collision site soon after the collision.[3][d]

A very few words will suffice for summing up, in conclusion, the causes of this accident. A man was selected by the company for the important duty of head guard to a heavy train who proved to be anything but trustworthy and careful, and who, in not performing that duty with the attention that it required, caused the fracture of a defective coupling, and permitted the greater part of his train to run backwards down a steep gradient, on which it came into violent collision with a following train.

Tyler had not restricted his criticism to Cooke. The best insurance against failure of couplings was the selection of intelligent men of known character and steadiness for the execution of responsible duties. Cooke had worked for the company as a goods guard for eight years, and had acted as a guard on excursion trains over several summers.

It cannot for a moment be supposed that a man habitually trustworthy should on this occasion only have so far forgotten himself as to invite the passengers into his van, to smoke and drink with them, to employ them at his brake handle, and four times to fracture the couplings in one day by his carelessness; and if the company or their officers were not aware of his character previously, then it can only be said that they ought to have been aware of it, and that they ought to have used an amount of circumspection that would have prevented them from appointing a careless man, as he proves clearly to have been, to such important duties

For a train of 28 carriages, two brake vans were inadequate, more than 28 carriages were needed to hold a thousand pleasure-seeking excursionists without over-crowding, and to maintain good order in a thousand pleasure-seeking excursionists more was needed than two guards (who had their normal duties to perform). The accident would not have been avoided or mitigated by specifying a longer interval between trains, or by a greater use of the telegraph. Tyler also noted two points which, whilst having no bearing on the accident, were, he felt, indicative of 'a want of proper discipline in the administration of the company'

- the stipulation that the excursion was restricted to schoolchildren and their teachers had been systematically ignored

- the record-book at Round Oak station (which recorded the time of arrival and departure of trains - thereby recording whether the interval system was being correctly worked to) had been filled up some three weeks before the accident, and no replacement had yet been procured; for the three weeks before the accident no record had been kept.

Trial of the guard

A coroner's inquisition was also held. In his summing up, the coroner directed the jury as follows

Almost all the scientific witnesses agreed in thinking that if Cook, the guard, had applied his brake in a proper manner when the carriages separated at the Round Oak Station, he would have stopped the train and have prevented the collision, and thus have avoided the death of the unfortunate deceased. If you believe that Cook could have done that in the ordinary performance of his duties, as guard on that occasion, and did not do so, Cook will have been guilty of manslaughter[5]

The jury duly found that Cooke should be charged with manslaughter.[6] The case was considered by the Grand Jury at Staffordshire Assizes in November 1858. In his charge to the Grand Jury, Mr Baron Bramwell took a very different view of the case, and of the law, from the coroner:

It did so happen that persons in the situation of Cook were made scapegoats of, in order to mollify public indignation at such occurrences, though he would not say such was the case on this particular occasion. He might also say that it was a very easy thing for scientific gentlemen to get quietly into a train and make experiments, with the knowledge that the result could bring them into no trouble, and then to say what they could do about stopping a train. This was very different from what a man would do in the hurry of the moment, and under such circumstances in which Cook was placed. If the guard mismanaged his brake, not from want of any intention or opportunity, but because he became frightened, it might show that the man was unfit for his situation, but it could not make him guilty of manslaughter.

"His lordship, having observed … that there was evidence to show that the guard was doing his best to stop the train by applying the brake, went on to remark that"

when a man had a duty to perform, if he performed it negligently, and death ensued in consequence, he was liable for the consequences; but a man was not guilty of manslaughter merely because he did not do that which a stronger or more clever or cool-headed person would have done under similar circumstances. There must, in fact, be culpability or something blameable in the prisoner to warrant the grand jury in finding a true bill[7]

The grand jury found no case to answer; Cook was then charged on the basis of the coroner's inquisition, but no evidence was offered and he was duly acquitted.[e] Reporting this, the Worcestershire Chronicle noted "This result entirely fulfils our prognostications as to the failure of this unfounded and unjustifiable prosecution."[7]

See also

Notes

- ^ At least one of the coaches was a brake carriage, with a handbrake which could be attended to by a guard in a compartment separate from the passengers, but was not manned on the excursion train

- ^ One victim died of her injuries subsequently, and in the jurisdiction of a different coroner; there were therefore two inquests, but the second contained no significant new testimony

- ^ On a gradient such as that at Round Oak, ideally the train should have come to rest with slack in its couplings (ie with the rear van brake on and holding the train), so that the engine only progressively took up the full load of the train on restart. The guard in the rear van should not leave the van without checking that his brake was applied and holding the carriages; most easily achieved by easing the brake off and reapplying it as soon as the van eased back

- ^ At the coroner's inquest the OW&W produced witnesses from the management of the Midland Railway and the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to vouch for the OW&W's arrangements for excursion trains being consistent with those adopted on their lines. The assistant locomotive engineer of the Midland was also asked about technical aspects of the evidence: he agreed with Tyler that the brake had never been applied, but his belief was not that the guard had not been in the van during the runaway, but that he had been there but had panicked : "the break was never screwed on the right direction, but that the guard in the excitement of the moment screwed it off instead of on"[4] The judge at Staffordshire Assizes seems to have taken a similar view, and Tyler's report gives no reason for his belief that Cooke was not in the van.

- ^ He had been held in jail since the inquest verdict eight weeks earlier, and had incurred legal costs of £70. A public subscription was started to pay his legal bills. In the 1861 census he was living in Worcester, and a Railway Porter.

Sources

- ^ "The Railway Collision near Round Oak - The Coroner's Inquest". Worcestershire Chronicle. 1 September 1858. p. 1.

- ^ "The Railway Collision at Round Oak". Worcestershire Chronicle. 8 September 1858. p. 4.

- ^ Tyler, Captain H.W. (16 October 1858). Oxford, Worcester, and Wolverhampton Railway (PDF). London: Board of Trade. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ "The Railway Catastrophe near Dudley". Worcestershire Chronicle. 6 October 1858. p. 4.

- ^ "The Late Railway Collision". Worcester Journal. 9 October 1858. p. 9.

- ^ http://www.84f.com/chronology/1850s/18581006BP.html

- ^ a b "The Railway Accident at Round Oak: No Bill Against Cook, the Guard". Worcestershire Chronicle. 1 December 1858. p. 2.

- Rolt, L.T.C.; Kichenside, Geoffrey (1982) [1955]. Red for Danger (4th ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. pp. 178–181. ISBN 0-7153-8362-0.

External links

- Extracts from The Birmingham Post :

- The Railway Catastrophe near Dudley (1 October 1858)

- The Railway Accident near Bretell Lane, verdict of manslaughter against Cooke, the guard. (6 October 1858)