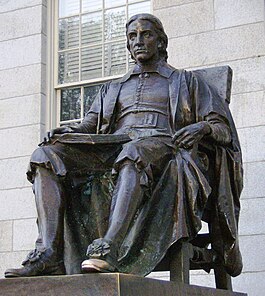

Statue of John Harvard

42°22′28″N 71°07′02″W / 42.37447°N 71.11719°W

| John Harvard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist |

|

| Year | 1884 |

| Type | Bronze |

| Dimensions |

|

| Location | Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Massachusetts |

John Harvard is a bronze sculpture by Daniel Chester French in Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Massachusetts honoring clergyman John Harvard (1607–1638), whose bequest, which included his personal library and a monetary gift, positioned him as the namesake for Harvard University.[2] After Harvard's death, Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered "that the Colledge agreed upon formerly to bee built at Cambridg shalbee called Harvard Colledge." [3]

French cast the sculpture in 1884. Without any references for Harvard's appearance, French used a Harvard undergraduate as a model for the sculpture's face.

The statue's inscription, which reads, JOHN HARVARD • FOUNDER • 1638, is the subject of a question, traditionally recited for visitors, as to whether John Harvard justly merits the honorific founder. According to a Harvard official[who?], the founding of the college was not the act of one but the work of many, and John Harvard is therefore considered not the founder, but rather a founder, of the school, though the timeliness and generosity of his contribution have made him the most honored of these.[citation needed]

Tourists often rub the toe of John Harvard's left shoe for luck, in the mistaken[citation needed] belief that doing so is a Harvard student tradition.

Composition

The New York Times described the statue at its unveiling:

The young clergyman is represented sitting, holding an open [book] on his knee. The costume is the simple clerical garb of the seventeenth century ... low shoes, long, silk hose, loose knee breeches, and a tunic belted at the waist, while a long cloak, thrown back, falls in broad, picturesque folds.[note 1]

John Harvard's gift to the school was £780 and—perhaps more importantly[M][11]—his 400-volume scholar's library:[12]

Partly under the chair, within easy reach, lie a pile of books.[note 1]

That he had died of tuberculosis, at about age thirty, was one of the few things known about John Harvard at the time of the statue's composition; as dedication orator George Edward Ellis put it:

Gently touched by the weakness which was wasting his immature life,[note 2] he rests for a moment from his converse with wisdom on the printed page, and raises his contemplative eye to the spaces of all wisdom.

Historian Laurel Ulrich suggests that John Harvard's general composition may have been inspired by Hendrik Goltzius' engraving of Clio, and that the figure's collar, buttons, tassel, and mustache may have been taken from a portrait of Plymouth Colony Governor Edward Winslow.[8]

History

On June 27, 1883, at the Commencement Day dinner of Harvard alumni a letter was read[M] from "a generous benefactor, General Samuel James Bridge, an adopted alumnus of the college":[9][note 3]

To the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Gentlemen, — I have the pleasure of offering you an ideal statue in bronze, representing your founder, the Rev. John Harvard, to be designed by Daniel C. French of Concord ... I am assured that the same can be in place by June 1, 1884.[M]

Bridge specified an "ideal" statue because there was then (as now)[2] nothing to indicate what John Harvard had looked like; thus when French began work in September he used Harvard student Sherman Hoar as inspiration for the figure's face. "In looking about for a type of the early comers to our shores," he wrote, "I chose a lineal descendant of them for my model in the general structure of the face. He has more of what I want than anybody I know." [16] (Through his father Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar—chairman[M] of Harvard's Board of Overseers—Sherman Hoar was descended from a brother of Harvard's fourth president Leonard Hoar,[note 4] as well as from Roger Sherman, a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.[8])

The commission weighed heavily on French even as the figure neared completion. "I am sometimes scared by the importance of this work. It is a subject that one might not have in a lifetime," wrote the sculptor—who thirty years later would create the statue of Abraham Lincoln for the Lincoln Memorial—"and a failure would be inexcusable. As a general thing, my model looks pretty well to me, but there are dark days."[17]

French's final model was ready the following May and realized in bronze by the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company over the next several months. The cost was reportedly more than $20,000.[18]

The statue was installed—"looking wistfully into the western sky", said Harvard president Charles W. Eliot[M]—at the western end of Memorial Hall on the triangular city block then known as the Delta .[19] At its October 15, 1884 unveiling[M] Ellis gave "a singularly felicitous address, telling the story of the life of John Harvard, who passes so mysteriously across the page of our early history." [20]

In 1920 French wrote[21][22] to Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell desiring that the statue be relocated; in 1924[14][18][19] it was moved from Memorial Hall (then the college dining hall—a Harvard Lampoon drawing showed John Harvard dismounting his plinth, chair in tow, and holding his nose because he "couldn't stand the smell of 'Mem' any longer")[citation needed] to its current location on the west side of Harvard Yard's University Hall, facing Harvard Hall, Massachusetts Hall, and the Johnston Gate.[note 5] Later that year the Lampoon imagined the frustrations of the metallic, immobile John Harvard surrounded by Harvard undergraduates—[18]

Great men arise / Before my eyes / From yonder pile I founded

While I must sit / Quite out of it / My jealousy unbounded

—though twelve years later David McCord portrayed the founder as satisfied in his stationarity:[23]

"Is that you, John Harvard?" / I said to his statue.

"Aye, that's me," said John, / "And after you're gone."

Sometime in the 1990s tour guides began encouraging visitors to emulate a "student tradition"—nonexistent—of rubbing the toe of John Harvard's left shoe for luck, so that while the statue as a whole is darkly weathered the toe now "gleams almost throbbingly bright, as though from an excruciating inflammation of the bronze." [note 6] It is, however, traditional for seniors, as they process to graduation exercises on Commencement Day (), to remove their caps as they pass.[18][24]

The statue is depicted on the United States Postal Service's 1986 John Harvard stamp (part of its Great Americans series).[25]

Seals and inscriptions

The facts as to John Harvard's relation to the founding of the College ... are entirely compatible with the inscription on John Harvard's statue. There is no myth to be destroyed.

The monument's six-foot[15] granite plinth is by Boston architect Charles Howard Walker.[18] On its southern side (the side to the viewer's right), in bronze, is the seal of John Harvard's alma mater, the University of Cambridge's Emmanuel College; on the northern side is what Ellis called "that most felicitously chosen of all like devices, the three open books and the veritas of Harvard. The pupil of the one institution was the founder of the other, transferring learning from its foreign home to this once wilderness scene." [9][note 8] On the rear are the words GIVEN BY • SAMUEL JAMES BRIDGE • JUNE 17, 1883.[note 9]

The face of the plinth is inscribed (in letters originally gilt)[M] JOHN HARVARD • FOUNDER • 1638—words "hardly read before some smartass guide breezily informs the unsuspecting visitor that this is, after all, the 'Statue of the Three Lies'" (as Douglas Shand-Tucci put it)[14] because (as is ritually related to freshmen and visitors):[10]

- the statue is not a likeness of JOHN HARVARD;

- it was the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—not John Harvard—which first voted "to give 400£ towards a schoale or Colledge", preempting any claim for John Harvard as FOUNDER; and

- the Court's vote came in 1636, not in the inscription's 1638—the latter being merely the year of John Harvard's bequest to the school.

However (Shand-Tucci continues) "the idea of the three lies is at best a fourth, and by far the greater falsehood," [14] as detailed in a 1934 letter to the Harvard Crimson from the secretary of the Harvard Corporation and director of the school's then-upcoming Tercentenary Celebration:

The facts as to John Harvard's relation to the founding of the College are not at all in dispute nor can it be said that the statue in front of University Hall does any violence to them. No likeness of John Harvard having been preserved, the statue [is an "ideal" representation].

If the founding of a university must be dated to a split second of time, then the founding of Harvard should perhaps be fixed by the fall of the president's gavel in announcing the passage of the vote of October 28, 1636 [see History of Harvard University]. But if the founding is to be regarded as a process rather than as a single event [then John Harvard, by virtue of his bequest "at the very threshold of the College's existence and going further than any other contribution made up to that time to ensure its permanence"] is clearly entitled to be considered a founder. The General Court ... acknowledged the fact by bestowing his name on the College.

These are all familiar facts and it is well that they should be understood by the sons of Harvard. They are entirely compatible with the inscription on John Harvard's statue. There is no myth to be destroyed.[note 7]

Pranks

The work became the target of pranks soon after its unveiling.

1884 tarring

In 1884 The Harvard Crimson reported that, "Some ingenious persons covered the John Harvard statue last night with a coat of tar. The same persons presumably, marked a large '87 on the wall at the entrance of the chapel," [28] and in 1886 the Crimson mentions a further incident: "A graduate contributor to the Advocate suggests that the editors of the college papers ferret out the authors of the small disturbances, such as the painting of the John Harvard statue." [29]

1890 painting

Following a May 31, 1890 Harvard athletic victory, front-page headlines in the Boston Morning Globe declared: "Vandalism at Harvard; statue of John Harvard and college buildings daubed with red paint by drunken students; seniors and faculty indignant ... Riotous Mob Ruled the Campus." [30]

The next day the Globe further reported that a Harvard student observing graffiti-removal efforts "declared that no Harvard man ever daubed the impious phrase, 'To h—l with Yale.' He was of the opinion that a Harvard man would at least soften the profanity by varnishing it with Latin or Greek ... Two detectives who were requested to ferret out the perpetrators paid little heed to the discussion on swear words, but kept their eyes on several impressions that had been made on the paint when it was fresh. One thought they were made by a dog's paws, and as several students kept dogs the suspicion was magnified to the importance of a clue. A student, however, told the detectives that according to his view the impressions were made by barefoot boys walking on tip-toe." [31]

Out-of-state newspapers reporting the outrage, and to a greater or lesser degree following the subsequent investigation, included (among many others):

- The World (New York, New York; June 2, p. 2): "A Jocular Outrage — Harvard Students Exceed Decency in Celebrating."

- Evening Gazette (Sterling, Illinois; June 2, p. 4): "Harvard Students on an Outrageous Tear. — Slathers of Red Paint Used. — The Fine Statue of the College Founder Ruined by the Crazy Scapegraces."

- Fort Wayne Sentinel (Fort Wayne, Indiana; June 2, p. 5): "The faculty will expel the criminals and persecute [sic] them if found."

- The Philadelphia Record: "Painted Harvard Red — Disgraceful Antics of Rum-Crazed Students. — Cambridge is Horrified. — The Faculty Bent on Vengeance ... Last night the whole college celebrated a wild orgie [sic] ... There were suppers, bonfires, fish-horns and a general pandemonium; but, save the insane acts of two of the students, who, overcome with enthusiasm, deliberately threw their dress coats into the bonfire while dancing around the blaze, no great overt act was then committed ... It was during the small hours that the vandals were abroad ... [John Harvard's] face, hands, books, and shoes were bright crimson, and his clothes striped like a zebra." [32]

Despite a mass meeting of outraged Harvard men (who insisted the culprits must be outsiders or, failing that, freshmen), the hiring of detectives, and an apparently facetious report that Harvard President Charles W. Eliot was unavailable for comment because he had "gone out in the woods to cut switches" (all Globe, June 3), on June 22 an anonymous contributor (Globe, p. 20) intimated that while "the faculty claim that they have not found out any of the men who did the 'fine art' work ... I saw the ringleader on class day showing two very pretty girls around the 'yard'."

Other incidents

In March 1934 Harvard athletes were suspected in the disappearance of Yale's "ugly bulldog mascot", Handsome Dan.[33][34][35] The dog was recovered a few days later, though not before the Harvard Lampoon had photographed him licking John Harvard's boots,[36][37] which had been smeared with hamburger.[35] ("Dog licks man", a Crimson headline read.)[38]

"Some years ago some students painted [the statue] crimson and our cops caught them red-handed", Deputy Chief of the Harvard University Police Jack W. Morse told The Harvard Crimson in 1984, adding "I've been waiting a long time to use that." [18] (Crimson is Harvard's school color.)[39]

As the statue's hundredth anniversary approached, Harvard Lampoon president Conan O'Brien predicted that "we'll probably stuff it with cottage cheese, maybe also with some chives." [18] "I think it’s creative but I wish students would direct their creative energies elsewhere," a Harvard maintenance official said in 2002.[40]

"Idealization" dispute

The challenge of creating an idealized representation of John Harvard was discussed by Ellis at the October 1883 meeting of the Massachusetts Historical Society:[9]

A very exacting demand is to be made upon the genius and skill of the artist ... The work must be wholly ideal, guided by a few suggestive hints, all of which are in harmony with grace, delicacy, dignity, and reverential regard. There is necessarily much that is unsatisfactory in a wholly idealized representation by art of an historical person of whose form, features, and lineaments there are no certifications. But the few facts [known with certainty] concerning Harvard are certainly helpful to the artist.

But Society president Robert Charles Winthrop harshly disapproved:

It must be altogether a fancy sketch, a 'counterfeit presentment,'—to use Shakespeare's phrase,—and in more senses of the word than one ... [S]uch attempts to make portrait statues of those of whom there are not only no portraits, but no records or recollections, are of very doubtful desireableness ... Such a course tends to the confusing and confounding of historic truth and leaves posterity unable to decide what is authentic and what is mere invention ... It seems to me of very questionable expediency to get up a fictitious likeness of him and make up a figure according to our ideas of the man.

A year later, in his oration[M] before the unveiling of what he called "a simulacrum ... a conception of what Harvard might have been in body and lineament, from what we know that he was in mind and in soul", Ellis answered Winthrop's criticism:

This exquisite moulding in bronze serves a purpose for the eye, the thought, and sentiment, through the ideal, in lack of the real ... It is by no means without allowed and approved precedent, that, in the lack of authentic portraitures of such as are to be commemorated, an ideal representation supplies the vacancy of a reality. It is one of the fair issues between poetry and prose.

The wise, the honored, the fair, the noble, and the saintly, are never grudged some finer touches of the artist in tint or feature, which etherialize their beauty, or magnify their elevation, as expressed in the actual body,—the eye, the brow, the lip, the moulding of the mortal clay. To flatter is not always to falsify.

Should there ever appear, however,

some authentic portraiture of John Harvard, the pledge may here and now be ventured, that some generous friend, such as, to the end, shall never fail our Alma Mater, notwithstanding her chronic poverty, will provide that this bronze shall be liquified again, and made to tell the whole known truth so as by fire.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "The John Harvard Statue" (PDF). The New York Times. October 18, 1884.

In quoting this passage the word book has been substituted for Bible per the unanimity of other sources,[M][4]: 279 [5][6]: 522 [7][8]

all of which refer to the volume held by the figure as a book or tome, but not specifically a Bible.

In the planning of the costume, "It was understood that Harvard was a clergyman educated at Cambridge, and, following as he did the fortunes of other clergymen who came to Massachusetts in the early period, he would be likely to be a Puritan of their stamp,—that is to say, not a Separatist. Pictures represent the Puritan minister of that day as wearing a somewhat closely fitting cloak, covering perhaps a cassock, with a broad linen collar and a skull-cap. The narrow bands and the wig came in later. No mistake could be made in the garment worn over the lower part of the body." [9]

That John Harvard is wearing a skullcap is frequently overlooked. "Edward T. Wilcox, A.M. '49 ... had a 38-year tenure at the College, during which he no doubt won many a highball with the following challenge [which he repeated during remarks at a 1974 ceremony honoring long-serving University employees]. 'How many of you would be prepared to bet one way or the other ... if I told you John Harvard is actually wearing a cap?'" [10]

Other subtle details are a slight mustache, tassels at the collar, and "roselike decorations" on the shoes.[8]

- ^ Per Memorial of John Harvard,[M] Ellis spoke of illness threatening Harvard's "immature" life, but the Crimson reporter understood Ellis to be speaking of Harvard's "miniature" life.[13]

"If I remember aright," French was quoted in 1899 as saying, John Harvard "is described as being 'reverend, godly, and a lover of learning,' and it is known that he died at an early age (about thirty) of consumption, which gave a clue to his physique." (French's daughter wrote[14] of the figure's "beautiful, wasted hand ... the hands were thin and nervous"; Shand-Tucci[14] mentions the "scrawny calves.") French continued, "It may possibly be of interest that my regular model for the statue, except the face, was a young Englishman, a graduate of Oxford, who was temporarily embarrassed financially and took this means of earning his bread." [15]

- ^ Joseph Hodges Choate, presiding at the dinner, "referred to the giver as 'a pious worshipper at Harvard's shrine, turning his face towards Mecca;' and, when the letter was read, the applause of the company compelled Mr. Bridge to make a silent acknowledgement".[M]

- ^ Nourse, Henry Stedman (1899). The Hoar Family in America. (See family tree at end of transcription.) "Leonard Hoar, designated in his father's will to be the scholar of the family and a teacher in the church," became in 1672 the first Harvard president to have also been a Harvard graduate. "In Sewall's Diary, June 15, 1674, is an account of the flogging of an undergraduate before the assembled students in the Library, President Hoar prefacing and closing the exercises with prayer. But this was not a very unusual discipline in those days and Dr. Hoar is not charged with undue severity."

- ^ Bunting, Bainbridge (1998). Harvard: An Architectural History. p. 290, n.14. ISBN 9780674372917: "The transfer of the statue from its original site on the Delta to a position on axis with Charles McKim's Johnston Gate was intended to give a sense of large-scale planning to the Yard and also to ameliorate the awkwardness of the central portion of Bulfinch's facade of University Hall."

- ^ a b Though noting that "students do rub bronze body parts [including noses and 'pedal extremeties'] at many schools and colleges", and that Dean of Students Archie Epps confessed to having once "insinuated himself into a group of tourists admiring the statue and whispered, 'I wonder if you'd get good luck if you rubbed his foot'", Harvard Magazine attributed persistence of the Harvard rub-for-luck faux tradition to the "mythmaking" of tour guides, who "assure their flocks that undergraduates have traditionally rubbed John Harvard's foot for luck (before exams or a mixer). They invite the tourists to do the same, and the tourists, being game and having paid their nickel, rub with gusto." Based on the estimate of a professor of materials science that "the shoe can endure 10 million rubs before it is utterly consumed", Harvard Magazine concluded that "the situation is grave": if 20,000 visitors per year each contribute "three brisk rubs (conservative estimates, surely), in 166 years John's toes will be history." [10]

- ^ a b Excerpted from Greene, Jerome Davis (December 11, 1934). "Don't Quibble Sybil — The Mail" (Letter to the editor)". Harvard Crimson. ("Don't quibble, Sybil" is a line from Noël Coward's 1930 Private Lives.) Greene's scold to "the sons of Harvard" opens, "The quibble over the question whether John Harvard was entitled to be called the Founder of Harvard College seems to me one of the least profitable. The destruction of myths is a legitimate sport, but its only justification is the establishment of truth in place of error." Greene was responding to a November 26 Crimson item iconoclastically headlined "Memorial Society Honors Founder of College In the Name and Image of Two Other Men — College Founded By Grant of the Massachusetts General Court in the Year 1636" : "When the members of the Memorial Society place a wreath on the statue of John Harvard today, expecting to honor the memory and the image of the founder of Harvard College, they will be honoring the likeness of another man and the name of a man who was not the legal founder of the college."

- ^ The modern design of the Harvard College seal features the syllables ve • ri • tas ("truth") superimposed on three books opened face up, with their pages to the viewer. The seal on the plinth, however, is an earlier design (the "Quincy seal", itself based on a long-forgotten 17th-century design rediscovered by president Josiah Quincy in the 1830s)[27] in which the third book is opened face down, with the letters tas over cover, spine, cover.

- ^ [M] Additionally, on either side of base of the bronze sculpture are THE HENRY-BONNARD BRONZE CO. • NEW YORK 1884 and DANIEL C. FRENCH • 1884.[1]

Sources and further reading

- Further reading

- Other sources cited

- ^ a b "John Harvard (sculpture)". Smithsonian American Art Museum – Inventory of American Sculpture. Control number IAS 77000368

- ^ a b Conrad Edick Wright, John Harvard: Brief life of a Puritan philanthropist Harvard Magazine. January–February, 2000.

- ^ The Charter of the President and Fellows of Harvard College

- ^ "Sitting Statues. John Harvard". American Architect and Architecture. Vol. XIX, no. 546. J. R. Osgood & Company. June 12, 1886. pp. 279–81.

- ^ The National Cyclopedia of American Biography. Vol. VIII. J. T. White. 1898. p. 285.

- ^ Badger, Henry C. (July–August 1887). "Notes from Harvard College: Its physical basis and intellectual life". In Lamb, Martha J. (ed.). The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Vol. 18. A. S. Barnes. pp. 517–22.

- ^ Talmage, T. De Witt, ed. (April 1885). "Statue of John Harvard". Frank Leslie's Sunday Magazine. Vol. 17, no. 4. Frank Leslie's Publishing House. p. 353.

- ^ a b c d e Ireland, Corydon (October 2, 2013). "Biography of a bronze". Harvard Gazette.

Then there are the hard-to-see books scattered under the statue's chair, companions to the single volume on his lap. (It's not a Bible.)

- ^ a b c d "Communication by George E. Ellis on the proposed Statue of John Harvard." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. XX (1882–1883), pp 345–350.

- ^ a b c The College Pump: Toes Imperiled. Harvard Magazine May–June 1999.

- ^ Alfred C. Potter, "The College Library." Harvard Illustrated Magazine, vol. IV no. 6, March 1903, pp. 105–112.

- ^ Potter, Alfred Claghorn (1913). Catalogue of John Harvard's library. Cambridge: J. Wilson.

- ^ "The Unveiling of the Harvard Statue", Harvard Crimson, October 16, 1884.

- ^ a b c d e Shand-Tucci, Douglas (2001). The Campus Guide: Harvard University. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 46–​, 51. ISBN 9781568982809.

- ^ a b Freeman. D. Bosworth, Jr., "The Statue of John Harvard", The Harvard Illustrated Magazine, vol. I, no. 2 (Nov. 1899), pp. 28–31.

- ^ Bethell, John T., Hunt, Richard M., Shenton, Robert. Harvard A to Z. Harvard University Press. 2004.[better source needed]

- ^ Richman, Michael. Daniel Chester French, an American sculptor (1983), p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g Callan, Richard L. (April 28, 1984). "100 Dears of Solitude: John Harvard Finishes His First Century". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ a b John Harvard to Move from Memorial Region: Will Take Up Position Before University Hall Some Time in May Harvard Crimson. March 22, 1924.

- ^ Bacon, Edwin M. (1886). Bacon's Dictionary of Boston. Houghton, Mifflin. p. 185.

- ^ Harvard Alumni Bulletin. 26 (30): 844. May 1, 1924.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Harvard University. President's Office. Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1909-1933. UAI.5.160, Box 202, Folder #566. Harvard University Archives.

- ^ Bethell, John T. (July–August 1997). "David McCord: Fishing with barbless hook". Harvard Magazine. The quotation is the entirety of McCord's poem "Man from Emmanuel", originally published in the Harvard Lampoon (1936).

- ^ Rose, Cynthia (May 1999). "Reading the Regalia: A guide to deciphering the academic dress code". Harvard Magazine.

- ^ usstampgallery.com: John Harvard

- ^ John Harvard's Fiftieth Anniversary Approaches — Statue First Erected in Front of Memorial Hall in 1884". Harvard Crimson, March 13, 1934.

- ^ Harvard University. Corporation. Seals, 1650–[1926];. UAI 15.1310, Harvard University Archives.

- ^ "Fact and Rumor". Harvard Crimson. November 15, 1884.

- ^ "Untitled". Harvard Crimson. February 26, 1886.

- ^ "Vandalism at Harvard". Boston Globe. June 2, 1890. p. 1.

- ^ Boston Morning Globe, p. 1, June 3, 1890

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Painted Harvard Red". The Philadelphia Record. June 2, 1890. p. 1.

- ^ "Harvard Honors 'Yard Cop' Chief". The New York Times. February 7, 1940. p. 13.

- ^ "Bingham Denies Mermen Kidnaped Handsome Dan – Advises Farmer Athletes Are Not Connected With Affair". The Harvard Crimson. March 21, 1934.

- ^ a b Untitled. Vol. 36. 1934. p. 730.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- ^ "Yale's Pet Back, But Photographs Show Treachery". Berkeley Daily Gazette. March 26, 1934.

- ^ "Handsome Dan II To Appear In Newsreel at University – Apted Figures in Filming of Stolen Yale Mascot". The Harvard Crimson. March 28, 1934.

- ^ "First Eli Bulldog Barked at Opponents In 1890; Second Licked Harvard's Feet". The Harvard Crimson. November 25, 1950.

- ^ "Color – Identity Guidelines – Harvard Business School". Harvard Business School. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ Ury, Faryl (October 2, 2002). "John Harvard Statue Vandalized". The Harvard Crimson.

External links

- Harvard: America's Great University Now Leads the World Life, vol. 10, no. 18 (May 5, 1941), cover (showing "John Harvard [statue] & Freshman") and pp. 22, 89–99.

- Josiah Quincy, History of Harvard College (title page showing "Quincy seal")

- Smithsonian American Art Museum – Inventory of American Sculpture – John Harvard (sculpture) – Detailed technical inventory

- 1884 establishments in Massachusetts

- 1884 sculptures

- Bronze sculptures in Massachusetts

- Harvard University

- Monuments and memorials in Massachusetts

- Outdoor sculptures in Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Sculptures by Daniel Chester French

- Sculptures of men in Massachusetts

- Statues in Massachusetts

- Vandalized works of art in Massachusetts

- Books in art