Religious satire

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

Religious satire is a form of satire that refers to religious beliefs and can take the form of texts, plays, films, and parody.[6] From the earliest times, at least since the plays of Aristophanes, religion has been one of the three primary topics of literary satire, along with politics and sex.[7][8][9] Satire which targets the clergy is a type of political satire, while religious satire is that which targets religious beliefs.[6] Religious satire is also sometimes called philosophical satire, and is thought to be the result of agnosticism or atheism. Notable works of religious satire surfaced during the Renaissance, with works by Geoffrey Chaucer, Erasmus and Albrecht Dürer.

Religious satire has been criticised and at times censored in order to avoid offence, for example the film Life of Brian was initially banned in Ireland, Norway, some states of the US, and some towns and councils of the United Kingdom. This potential for censorship often leads to debates on the issue of freedom of speech such as in the case of the Religious Hatred Bill in January 2006. Critics of the original version of the Bill (such as comedian Rowan Atkinson) feared that satirists could be prosecuted.

Notable examples of religious satire and satirists

- Brian Merriman

- Bill Maher

- George Carlin

- Bill Hicks

- Ricky Gervais

- Doug Stanhope

- Pat Condell

- Lenny Bruce

- Lucian of Samosata

- Dave Allen

- Hannibal Buress

- Jim Jeffries

- Richard Pryor

- Theo van Gogh

- Tim Minchin

- Douglas Adams

- Monty Python

- The Kids in the Hall

Films and documentaries

- St. Jorgen's Day, by Yakov Protazanov (1930)

- Elmer Gantry, by Richard Brooks (1961)

- Heavens Above!, by John and Roy Boulting (1963)

- The Holy Mountain (1973)

- Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

- Monty Python's Life of Brian (1979)

- Pray TV (1980)

- Monty Python's The Meaning of Life (1983)

- Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984)

- Orgazmo by Trey Parker and Matt Stone (1997)

- Dogma by Kevin Smith (1999)

- Saved! by Brian Dannelly (2004)

- Religulous by Larry Charles and Bill Maher (2008)

- Futurama: The Beast with a Billion Backs (2008)

- The Invention of Lying by Ricky Gervais and Matthew Robinson (2009)

- OMG – Oh My God by Umesh Shukla (2012)

- How to Lose Your Virginity (2013)

- PK by Rajkumar Hirani (2014)

- Sausage Party by Conrad Vernon and Greg Tiernan (2016)

Characters

- Zarquon is a legendary prophet from Douglas Adams' Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy who was worshipped by a number of people. His name was used as a substitute for "God".

Literature and publications

- Al-Fuṣūl wa Al-Ghāyāt ("Paragraphs and Periods"), a parody of the Quran by Al-Maʿarri[10] (10th-11th century)

- Collection of stories The Canterbury Tales (14th century) by Geoffrey Chaucer

- Essay The Praise of Folly (1509) by Desiderius Erasmus

- Novel A Tale of a Tub (1704) by Jonathan Swift

- Brian Merriman's Cúirt An Mheán Óiche (The Midnight Court) (c.1780), an Irish language comic poem which satirizes, among other things, the hypocrisy inherent in an 18th-century rural Ireland where Christian morality has collapsed

- Robert Burns' poem Holy Willie's Prayer (1785), which is an attack on self-righteousness and hypocrisy within the Calvinist Church of Scotland

- Chronicles of Barsetshire by Anthony Trollope (1855-67)

- Letters from the Earth, book of essays by Mark Twain

- Alexander the Oracle Monger, a parody and exposé of a false prophet by Lucian of Samosata

- The Screwtape Letters, by C. S. Lewis, 1943

- Christian satire and humor magazine The Wittenburg Door (1971-2008)

- Robert A. Heinlein's novel Job: A Comedy of Justice (1984)

- Christopher Moore's absurdist novel Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal (2002)

- The controversial "Islamophobic" Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons (2005)

Plays and musicals

- Tartuffe (1664) by Molière

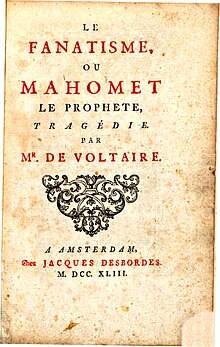

- Mahomet, ou Le fanatisme (1736) by Voltaire, notable for its critical depiction of Muhammad,[11] described as a self-deceived,[12] perverted[12] religious fanatic and manipulator,[11][12] and his hunger for political power behind the foundation of Islam.[11][12]

- Inherit the Wind (1955), which fictionalizes the Scopes Monkey Trial of the 1920s

- Mistero Buffo (1969) by Dario Fo.

- Jerry Springer: The Opera, notable for its irreverent treatment of Judeo-Christian themes

- A Very Merry Unauthorized Children's Scientology Pageant (2003), which makes fun of L. Ron Hubbard and Scientology

- Altar Boyz (2005) Off-Broadway musical about Christian Boysband

- Saturday's Voyeur is a parody of life in Utah and Mormon culture

- The Book of Mormon (2011) A broadway production about two young Mormon Missionaries sent to Uganda, written by South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone

- Letting Go of God (2004), Julia Sweeney, an autobiographical monologue taking aim at Catholicism and Mormonism

Television

- The Barchester Chronicles, 1982 television serial produced by the BBC, from the Anthony Trollope novels satirizing Victorian clergy

- Futurama episode "A Pharaoh to Remember" features a religious ceremony in which a priest chants, "Great Wall of Prophecy, reveal to us God's Will, that we might blindly obey!" and celebrants answer, "Free us from thought and responsibility."

- Curb Your Enthusiasm has episodes that have satirized Orthodox Judaism and Christianity

- South Park has satirized Christianity, Mormonism, Judaism, Islam, Scientology, and other religions

- Family Guy has satirized elements of Christianity and other religions in several episodes

- Satirical Australian documentary miniseries John Safran vs God (2004)

- British sitcom Father Ted, which lampooned the role of the Catholic Church in Ireland

- Blackadder episode "The Archbishop" sees Edmund invested as Archbishop of Canterbury amid a Machiavellian plot by the King to acquire lands from the Catholic Church. In Series 2, in the episode "Money", the Bishop of Bath and Wells comments "Never, in all my years, have I encountered such cruel and foul-minded perversity! Have you ever considered a career in the church?"

Characters

- Princess Clara of Drawn Together is a devout Christian who is often used to lampoon conservative Christian viewpoints

- Ned Flanders of The Simpsons is an Evangelical Christian who practices sola scriptura

On the web

- Sinfest, an internet comic strip by Tatsuya Ishida that frequently stresses religious issues (since 2000)

- Semiweekly comic Jesus and Mo (since 2005)

- Comedic short film series Mr. Deity, which stars God, his assistant, Jesus, Lucifer, and several other characters from the Bible (since 2006)

- The LOLCat Bible Translation Project, a wiki-based project by Martin Grondin (since 2007)

- Net Authority, a site that purported to be a Christian Internet censorship site (2001-2008).

- The Babylon Bee, a parody news site, mainly focusing on satirizing American Evangelical Christianity from a conservative Evangelical perspective (since 2016)

People

- Betty Bowers plays a character called "America's Best Christian". In the persona of a right-wing evangelical Christian, she references Bible verses, using the persona to point out the inconsistencies in the Bible

Parody religions

- The Satanic Temple is a left-wing activist group that uses satanic imagery to shock and protest primarily in support of the separation of church and state, reproductive rights, and social justice. They sought out and were granted tax-exempt status by the IRS in 2019 in an effort to bolster their perceived legitimacy in their numerous legal battles. Most famously, they are fighting against religious preference by the US government, and are attempting to use the same tactics that Christian groups use to persuade the US government to allow equal religious representation on government land, not just the religions they favor.

- Boogyism is a fun loving cult that follows the teachings of The Great Booga, an 8 ft stuffed bunny look-alike who created the entire universe after an accident involving an unattended barbecue. It has its own religious text, The Spiritual Arghh.

- The Flying Spaghetti Monster is the deity of the "Pastafarian" parody religion, which asserts that a supernatural creator resembling spaghetti with meatballs is responsible for the creation of the universe. Its purpose is to mock intelligent design.

- The Invisible Pink Unicorn is a goddess which takes the form of a unicorn that is paradoxically both invisible and pink. These attributes serve to satirize the apparent contradictions in properties which some attribute to a theistic God, specifically omniscience, omnipotence, and omnibenevolence.

- Discordianism is centered around the ancient Greco-Roman goddess of chaos, Eris, but draws much of its tone from Zen Buddhism, Christianity, and the beatnik and hippie countercultures of the 1950s and 1960s (respectively). Its main holy book, the Principia Discordia contains things such as a commandment to "not believe anything that you read," and a claim that all statements are both true and false at the same time.

- The Church of the SubGenius pokes fun at many different religions, particularly Scientology, Televangelism (and its associated scandals), and other modern beliefs.

- The worship of "Ceiling Cat" among Lolcats. Ceiling Cat's enemy is Basement Cat, a black cat representing the devil.

Miscellaneous

- Voltaire

- The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a street performance organization that uses Catholic imagery to call attention to sexual intolerance and satirize issues of gender and morality.

- The Brick Testament, a project in which the stories of the Bible are illustrated with Lego.

- Purim Torah, traditional parodies of Jewish life written out, and/or acted out, for the holiday of Purim.

- Sheep by progressive rock band Pink Floyd includes a humorous version of Psalm 23.

Reactions, criticism and censorship

Religious satire has been criticized by those who feel that sincerely held religious views should not be subject to ridicule. In some cases religious satire has been censored - for example, Molière's play Tartuffe was banned in 1664.

The film Life of Brian was initially banned in Ireland, Norway, some states of the US, and some towns and councils of the United Kingdom.[13] In an interesting case of life mirroring art, activist groups who protested the film during its release bore striking similarities to some bands of religious zealots within the film itself.[14] Like much religious satire, the intent of the film has been misinterpreted and distorted by protesters. According to the Pythons, Life of Brian is not a critique of religion so much as an indictment of the hysteria and bureaucratic excess that often surrounds it.[15]

The issue of freedom of speech was hotly debated by the UK Parliament during the passing of the Religious Hatred Bill in January 2006. Critics of the original version of the Bill (such as comedian Rowan Atkinson) feared that satirists could be prosecuted, but an amendment by the House of Lords making it clear that this was not the case was passed - by just one vote.[16]

In 2006, Rachel Bevilacqua, a member of the Church of the SubGenius, known as Rev. Magdalen in the SubGenius hierarchy, lost custody and contact with her son after a district court judge took offense at her participation in the Church's X-Day festival.[citation needed]

See also

- Anti-Catholic satire and humor

- The Bible and humor

- Discordianism

- Humour in Islam

- Jewish humour

- Parody religion

- Religion in The Simpsons

References

- ^ Oberman, Heiko Augustinus (1 January 1994). "The Impact of the Reformation: Essays". Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing – via Google Books.

- ^ Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 By Mark U. Edwards, Jr. Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8006-3735-4

- ^ In Latin, the title reads "Hic oscula pedibus papae figuntur"

- ^ "Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim ban, Und sey nicht so zorniger man. Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre, Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere"

- ^ Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 (2004), p. 199

- ^ a b Hodgart (2009) p.39

- ^ Clark (1991) pp.116-8 quotation:

...religion, politics, and sexuality are the primary stuff of literary satire. Among these sacret targets, matters costive and defecatory play an important part. ... from the earliest times, satirists have utilized scatological and bathroom humor. Aristophanes, always livid and nearly scandalous in his religious, political, and sexual references...

- ^ Clark, John R. and Motto, Anna Lydia (1973) Satire--that blasted art p.20

- ^ Clark, John R. and Motto, Anna Lydia (1980) Menippeans & Their Satire: Concerning Monstrous Leamed Old Dogs and Hippocentaurs, in Scholia satyrica, Volume 6, 3/4, 1980 p.45 quotation:

[Chapple's book Soviet satire of the twenties]...classifying the very topics his satirists satirized: housing, food, and fuel supplies, poverty, inflation, "hooliganism", public services, religion, stereotypes of nationals (the Englishman, German, &c), &c. Yet the truth of the matter is that no satirist worth his salt (Petronius, Chaucer, Rabelais, Swift, Leskov, Grass) ever avoids man's habits and living standards, or scants those delicate desiderata: religion, politics, and sex.

- ^ Editors (May 2018). "Al-Maʿarrī (Biography)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c Quinn, Frederick (2008). The Sum of All Heresies: The Image of Islam in Western Thought. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-0-19-532563-8.

- ^ a b c d Almond, Philip C. (1989). Heretic and Hero: Muhammad and the Victorians. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 33–35. ISBN 3-447-02913-7.

- ^ Vicar supports Life of Brian ban

- ^ Dyke, C: Screening Scripture, pp. 238-240. Trinity Press International, 2002

- ^ "The Secret Life of Brian". 2007.

- ^ "Votes on the Racial and Religious Hatred Bill". 2006.