Buxton

| Buxton | |

|---|---|

Buxton town centre | |

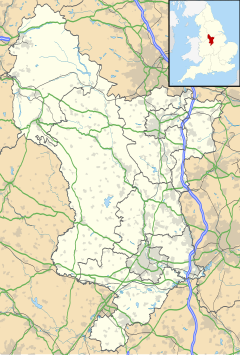

Location within Derbyshire | |

| Population | 22,215 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SK059735 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BUXTON |

| Postcode district | SK17 |

| Dialling code | 01298 |

| Police | Derbyshire |

| Fire | Derbyshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Buxton, a spa town in Derbyshire is the highest market town in England, some 1,000 feet (300 m) above sea level.[1][nb 1][citation needed] Buxton is close to the county boundaries of Cheshire to the west and Staffordshire to the south, on the edge of the Peak District National Park.[1] The municipal borough merged in 1974 with places that included Glossop to form the local government district and borough of High Peak. The town population was 22,115 at the 2011 Census. Sights include Poole's Cavern, a limestone cavern open to the public, St Ann's Well, fed by a geothermal spring bottled and sold by Buxton Mineral Water Company, and several Georgian buildings round John Carr's restored Buxton Crescent, including Buxton Baths. Also notable is the Frank Matcham-designed Buxton Opera House, which hosts music and theatre events. The Devonshire Campus of the University of Derby occupies historic buildings in the town. Buxton is twinned with Oignies, France, and Bad Nauheim, Germany.[2]

History

The origins of the town's name are uncertain. It may be derived from the Old English for Buck Stone or for Rocking Stone.[3] The town grew in importance in the late 18th century when it was developed by the Dukes of Devonshire, with a resurgence a century later as the Victorians were drawn to the reputed healing properties of the waters.[4]

Stone Age past

The first inhabitants of Buxton made their home at Lismore Fields 6,000 years ago. The Stone Age settlement (a Scheduled Monument) was discovered in 1984 with remains of a Mesolithic timber roundhouse & Neolithic longhouses.[5]

Roman settlement

The Romans developed a settlement known as Aquae Arnemetiae[1] (or the baths of the goddess of the grove). The discovery of coins indicates that the Romans were in Buxton throughout their occupation.[6] Batham Gate ("road to the bath town") is a Roman road from Templebrough Roman fort in South Yorkshire to Navio Roman Fort and on to Buxton.

Middle Ages

The town's name Buckestones was first recorded in the 12th-century as part of Peverel family's estate. From 1153 the town became part of the Duchy of Lancaster's Crown estate, close to the Royal Forest of the Peak (which lay on the Fairfield side of the River Wye). In the 1200s monastic farms were set up in Fairfield. In the 1300s the town's Royal ownership was reflected in its name of Kyngesbucstones. By 1460 Buxton's spring had been pronounced a holy well dedicated to St Anne (who was canonised in 1382) and a chapel had been built by 1498.[7]

Spa town boom

Built on the River Wye, and overlooked by Axe Edge Moor, Buxton has a history as a spa town due to its geothermal spring[8] which rises at a constant temperature of 28 °C. The spring waters are piped to St Ann's Well (a shrine to St. Anne since medieval times) at the foot of The Slopes, opposite the Crescent near the town centre.[9] The well was declared to be one of the Seven Wonders of the Peak by philosopher Thomas Hobbes in his 1636 book De Mirabilibus Pecci: Being The Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire.[10]

The Dukes of Devonshire have been closely involved with Buxton since 1780, when the 5th Duke used the profits from his copper mines to develop the town as a spa in the style of Bath. Their ancestor Bess of Hardwick had taken one of her four husbands, the Earl of Shrewsbury, to "take the waters" at Buxton shortly after he became the gaoler of Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1569, and they took Mary there in 1573.[citation needed] She called Buxton "La Fontagne de Bogsby", and stayed at the site of the Old Hall Hotel. The area features in the poetry of W. H. Auden and the novels of Jane Austen and Emily Brontë.[8]

Instrumental in the popularity of Buxton was the recommendation by Erasmus Darwin of the waters at Buxton and Matlock to Josiah Wedgwood I. The Wedgwood family often went to Buxton on holiday and recommended the area to their friends.[citation needed] Two of Charles Darwin's half-cousins, Edward Levett Darwin and Reginald Darwin, settled there.[11] The arrival of the railway in 1863 stimulated the town's growth: the population of 1,800 in 1861 had grown to over 6,000 by 1881.[12]

20th century

During World War I, Buxton was a base for British and Canadian troops. Granville Military Hospital was set up at the Buxton Hydropathic Hotel and the Palace Hotel was used as an annexe to it. The author Vera Brittain trained as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse at the Devonshire Hospital in 1915. The Royal Engineers based in Buxton used the Pavilion Gardens' lakes for training exercises to build pontoon bridges.[7][13][14]

RAF Harpur Hill was established as an underground bomb storage facility during World War II and it became the largest munitions dump in the country. It was also the base for the Peak District section of the RAF Mountain Rescue Service.[15]

Following the decline of Buxton as a spa resort over the first half of the 20th century, the town saw a resurgence as an entertainment destination between the 1950s and 1970s. The Playhouse Theatre had its own reperatory company, pop concerts were held at the Octagon (including The Beatles in 1963[16]), the Opera House re-opened in 1979 with the launch of the Buxton Festival and the town became popular as a base for exploring the Peak District.[17]

Notable architecture

With the increasing popularity of Buxton's thermal waters in the 18th and 19th centuries, a number of buildings were commissioned to provide for the hospitality of tourists retreating to the town.

The Old Hall Hotel is one of the oldest buildings in Buxton. It was owned by George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. He and his wife, Bess of Hardwick, were the "gaolers" of Mary, Queen of Scots. She came to Buxton several times to take the waters, the last time in 1584. The present building dates from 1670 and has a five-bay front with a Tuscan doorway.[18]

The Grade I listed Crescent was built between 1780 and 1784, for William Cavendish, the 5th Duke of Devonshire, as part of his scheme to establish Buxton as a fashionable Georgian spa town. Modelled on Bath's Royal Crescent, it was designed by architect John Carr, along with the neighbouring irregular octagon and colonnade of the Great Stables.

The Great Stables were completed in 1789, but in 1859 were largely converted to a charity hospital for the 'sick poor' by the 7th Duke of Devonshire's architect Henry Currey, who also worked on St Thomas' Hospital in London. It became known as the Devonshire Royal Hospital in 1934. Later phases of the conversion following 1881 were by local architect Robert Rippon Duke. These included his design for The Devonshire Dome, which was the world's largest unsupported dome with a diameter of 144 feet (44 m), larger than the Pantheon at 141 feet (43 m), St Peter's Basilica at 138 feet (42 m) in Rome, and St Paul's Cathedral at 112 feet (34 m). The record was surpassed by space frame domes such as the Georgia Dome (840 feet (260 m)). The building and its surrounding Victorian villas are now part of the University of Derby.

Currey also designed the Grade-II-listed Buxton Baths, comprising the Natural Mineral Baths to the west of The Crescent, and Buxton Thermal Baths to the east, which opened in 1854 on the site of the original Roman baths, together with the 1884 Pump Room opposite. The Thermal Baths, closed in 1963 and at risk of demolition, were restored and converted into a shopping arcade by conservation architects Derek Latham and Company. Architectural artist Brian Clarke was commissioned to contribute to the refurbishment;[19][20] his scheme, designed in 1984 and completed in 1987, was for a landmark,[21] barrel-vaulted modern stained glass ceiling to enclose the former baths — at the time the largest stained glass window in Britain — creating an atrial space for what became the Cavendish Arcade.[21][22] Visitors could 'take the waters' at The Pump Room until 1981. Between 1981 and 1995 the building housed the unique Micrarium Exhibition.[23] The building is being refurbished as part of the National Lottery-funded Buxton Crescent and Thermal Spa re-development. Beside it, added in 1940, is St Ann's Well.

Nearby stands the elegant and imposing monument to Samuel Turner (1805–1878), treasurer of the Devonshire Hospital and Buxton Bath Charity, built in 1879 and accidentally lost for the latter part of the 20th century during construction work before being found and restored in 1994.[24] In October 2020 Ensana reopened the Crescent as a 5-star spa hotel, following its 17-year refurbishment.[25]

When the railways arrived in Buxton in 1863, Buxton railway station was opened under the design of Joseph Paxton, previously gardener and architect to William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire. Paxton also designed the layout of the Park Road circular estate; he is perhaps most famous for his design of the Crystal Palace in London.

Other architecture

Buxton Opera House was designed by Frank Matcham in 1903 and is the highest opera house in the country. Matcham was a prolific theatrical architect who designed several London theatres, including the London Palladium, the London Coliseum and the Hackney Empire. Opposite is an original Penfold octagonal post box. The opera house is attached to the Pavilion Gardens, Octagonal Hall (built in 1875) and the smaller Pavilion Arts Centre (previously called The Hippodrome and the Playhouse Theatre[26]). The Buxton Pavilion Gardens, designed by Edward Milner, contain 93,000 m² of gardens and ponds and were opened in 1871. The Pavilion Gardens is a Grade II* listed public park of Special Historic Interest and Milner's design was a development of Joseph Paxton's landscape design of the Serpentine Walks from the 1830s.[27]

The 122-room Palace Hotel, built in 1868, is a prominent feature of the Buxton skyline on the hill above the railway station. It was also designed by Currey.[28]

The town is overlooked by two landmarks. Atop Grin Low hill, 1,441 feet (439 m) above sea level, is Grinlow Tower (locally also called "Solomon's Temple"), a two-storey granite, crooked, crenelated folly built in 1834 by Solomon Mycock to provide work for the town's unemployed and restored in 1996 after a lengthy closure to the public. In the other direction, on Corbar Hill, 1,433 feet (437 m) above sea level, is Corbar Cross, a tall, wooden cross. Originally given to the Roman Catholic Church by the Duke of Devonshire in 1950 to commemorate Holy Year, it was replaced in the 1980s. In 2010, during the visit of Pope Benedict XVI to the UK, it was cut down as a protest against a long history of child abuse at the Catholic St Williams School in Market Weighton, Yorkshire.[30] The Buxton ecumenical group Churches Together organised several benefactors who replaced the cross with a smaller cross in May 2011.[29]

Many of the pubs and inns in Buxton are listed buildings and are an important part of the historical character of the town.[31]

Many prominent old buildings have been demolished. Lost buildings of Buxton include grand spa hotels, the Midland Railway station, the Picture House cinema and Cavendish Girls Grammar School.

Culture

Cultural events include the annual Buxton Festival, among other festivals and performances held in the Buxton Opera House, with shows running at other venues alongside this. Buxton Museum & Art Gallery offers year-round exhibitions.

Buxton Festival

The Buxton Festival, founded in 1979, is an opera and arts festival that runs for about three weeks in July at various venues including the Opera House.[32] The programme includes literary events in the mornings, concerts and recitals in the afternoon, and operas, many of them rarely performed, in the evenings.[33] There has been an increase in the quality of the operatic programme in recent years, after decades when, according to critic Rupert Christiansen, the festival featured "work of such mediocre quality that I just longed for someone to put it out of its misery."[34][35] Running alongside it is the Buxton Festival Fringe, known as a warm-up for the Edinburgh Fringe. The Buxton Fringe features drama, music, dance, comedy, poetry, art exhibitions and films in various venues around the town.[36] In 2018, 181 entrants signed up and comedy and theatre categories were at their largest.[37]

Other festivals

The week-long Four Four Time music festival is held every February and features a variety of rock, pop, folk, blues, jazz and world music.[38] The International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival, a three-week theatre festival from the end of July through most of August, was held in Buxton from 1994 to 2013; it moved to Harrogate in 2014.[39]

The Opera House has a year-long programme of drama, concerts, comedy and other events.[40] In September 2010, following a £2.5 million reconstruction, the former Paxton Suite in the Pavilion Gardens re-opened as a performance venue called the Pavilion Arts Centre. The centre, located behind the Opera House, includes a 369-seat auditorium. The stage area can be converted into a separate 93-seat studio theatre.[41][42]

Buxton Museum & Art Gallery has a permanent collection of local artefacts, geological and archaeological samples (including the William Boyd Dawkins collection) and 19th- and 20th-century paintings, including works by Brangwyn, Chagall, Chahine and their contemporaries. There are also regular exhibitions by local and regional artists and various other events.[43] The Pavilion Gardens hosts regular arts, crafts, antiques and jewellery fairs.[44]

Buxton's Well Dressing Festival takes place in the week running up to the second Saturday in July. The festival, in its current form, has been running since 1840 to celebrate the provision of fresh water to the high-point of the town's market place. As well as the dressing of the wells, the Festival involves a carnival procession and a funfair on the Market Place.[45] Well dressing is an ancient custom unique to the Peak District and Derbyshire, and is thought to date back to Roman and Celtic times, when communities would dress wells to give thanks for fresh water supplies.

Economy

Buxton's economy includes tourism, retail, quarrying, scientific research, light industry and mineral water bottling. The University of Derby is a significant employer.[citation needed] The town is surrounded by the Peak District National Park and offers a range of cultural events; tourism is a major industry, with more than a million visitors to Buxton each year. Buxton is the main centre for overnight accommodation within the Peak District, with more than 64% of the park's visitor bed space.[46]

The Buxton Mineral Water Company (owned by Nestlé) extracts and bottles mineral waters in Buxton.[47] A local newspaper, the Buxton Advertiser, is published weekly.

Potters of Buxton is the oldest department store in the town and surrounding area, established in 1860.[48]

Quarrying

The Buxton lime industry has shaped the town's development and landscape since its 17th-century beginnings. Buxton Lime Firms (BLF) was formed by 13 quarry owners in 1891. BLF became part of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in 1926 and Buxton was the headquarters for I.C.I. Lime Division until the 1970s.[49] Several limestone quarries are located close to Buxton,[50] including the "Tunstead Superquarry", the largest producer of high-purity industrial limestone in Europe, which employs 400 people.[51] The quarrying sector also provides employment in limestone processing[52] and distribution.[53] Other industrial employers include the Health & Safety Laboratory, which engages in health and safety research and incident investigations and maintains over 350 staff locally.[46][54][55]

Education

The town hosts a University of Derby campus at the site of the former Devonshire Royal Hospital, as well as the Buxton & Leek College formed by the August 2012 merger of the university with Leek College.

Secondary schools in the town include Buxton Community School (at the former College Road site of Buxton College) and St. Thomas More Catholic School.[56] Other nearby schools include Buxton Junior School,[57] St. Anne's Catholic Primary School,[58] Harpur Hill Primary School,[59] Buxton Infant School,[60] John Duncan School, Fairfield Infant & Nursery School, Burbage Primary School, Dove Holes C. E. Primary School, Fairfield Endowed Junior School, Peak Dale Primary School, Leek College, Old Sams Farm Independent School, Hollinsclough C.E Primary School, Flash C.E. Primary School, Earl Sterndale C of E Primary School, Peak Forest C of E Primary School and Combs Infant School.[61]

Sport and civic organisations

In the high land above the town there are two small speedway stadiums. Buxton Raceway (formerly High Edge Raceway), off the A53 Buxton to Leek road, is a motor sports circuit established in 1974, hosting banger and stock car racing, as well as drifting events.[62] It was the original home of the speedway team Buxton High Edge Hitmen in the mid-1990s before the team moved to the custom-built track immediately to the north of the original circuit. The original track at High Edge Raceway[63] was amongst the longest and trickiest tracks in the UK. The new track is of a more conventional shape and length with regular improvements to the venue being made. Buxton have been regular competitors in the Conference League.[64][65] With the recent addition of flood lighting, Buxton Raceway is due to hold the 2019 BriSCA F2 World Final at night which is expected to see large crowds.[66]

Buxton has a football club, Buxton F.C., who play at the Silverlands; a cricket club, Buxton Cricket Club, who play at the Park Road ground;[67] a Buxton Rugby Union club;[68] and a hockey club, Buxton Hockey Club.[69] In addition, four Hope Valley League football clubs are based in Buxton: Buxton Town, Peak Dale and Buxton Christians play at the Fairfield Centre, with Blazing Rag playing at the Kents Bank Recreation Ground.[citation needed]

There are two 18-hole golf courses in Buxton. On the western edge of the town is Cavendish Golf Club, which is ranked among the top 100 golf courses in England. Cavendish was designed by the renowned course architect Dr. Alister MacKenzie and dates from 1925.[70] In the eastern suburb of Fairfield is Buxton & High Peak Golf Club. Founded in 1887, on the site of the old Buxton Racecourse, it is the oldest in Derbyshire.[71]

The hillside around Solomon's Temple is a popular local bouldering venue with many small outcrops giving problems mainly in the lower grades. These are described in the 2003 guidebook High over Buxton: A Boulderer's Guide.[72] Hoffman Quarry at Harpur Hill, sitting prominently above Buxton, is a local venue for sport climbing.[73]

Youth groups include the Kaleidoscope Youth Theatre at the Pavilion Arts Centre,[74] Buxton Squadron Air Cadets,[75] Derbyshire Army Cadet Force and the Sea Cadet Corps, in addition to units from the Scouts & Guide Association.[citation needed]

Buxton is home to three Masonic Lodges, and one Royal Arch Chapter, which meet at the Masonic Hall in George Street. Phoenix Lodge of Saint Ann No.1235 was consecrated in 1865; Buxton Lodge No.1688 was consecrated in 1877 and High Peak Lodge No.1952 was consecrated in 1881. The Royal Arch Chapter is attached to Phoenix Lodge of Saint Ann, and bears the same name and number, it being consecrated in 1872.[76]

Media

Regional TV news is provided by Salford-based BBC North West and ITV Granada. Local radio stations are High Peak Radio on 106.4FM, and BBC Radio Derby on 96.0FM.

Public transport

Buxton railway station is served by Northern. It has frequent trains to Stockport and the city of Manchester. The journey from Buxton to Manchester Piccadilly takes just under an hour.[77] Buxton had three railway stations, two under the LNWR (Buxton and Higher Buxton; the latter was next to Clifton Road and closed in 1951) plus the Buxton railway station (Midland Railway) next to the LNWR terminus. The Midland Railway station was closed on 6 March 1967, later becoming the site for the Spring Gardens shopping centre. The trackbed of the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway has in part been used as a walk and cycleway called the Monsal Trail. Peak Rail, a heritage railway group, have restored the section from Rowsley to Matlock, with the long-term objective of re-opening it back to Buxton.

The town's buses include services into the Peak District National Park. Other buses run to the nearby towns of Whaley Bridge, Chapel en le Frith, New Mills, Glossop and Ashbourne, and the High Peak 'Transpeak' service offers an hourly link southwards to Taddington, Bakewell, Matlock, Belper and Derby. There is also a High Peak bus directly from Manchester Airport to Buxton.[78] Other[79] services link Buxton with Macclesfield, Leek, Stoke-on-Trent,[80] Sheffield, Chesterfield and Meadowhall. [81]

The nearest airports are Manchester Airport (22 miles), Liverpool John Lennon Airport (48 miles), and East Midlands Airport (52 miles).

There are also taxi services based in the town.

Geography and geology

Although outside the National Park boundary, Buxton is geologically in the Peak District and built between the Lower Carboniferous limestone of the White Peak and the Upper Carboniferous shale, sandstone and gritstone of the Dark Peak.[82] The early settlement (of which only the parish church of St Anne, built in 1625, remains) was largely of limestone construction[citation needed] while the present buildings, of locally quarried sandstone, mostly date from the late 18th century.[citation needed]

At the southern edge of the town the River Wye has carved an extensive limestone cavern, known as Poole's Cavern. More than 330 yards (300 metres) of its chambers are open to the public. The cavern contains Derbyshire's largest stalactite and there are unique 'poached egg' stalagmites. A notorious local highwayman called Poole gave the cavern its name.[83]

Climate

At about 1,000 feet (300 m) above sea level,[84] Buxton is the highest market town in England.[nb 1] Due to this relatively high elevation, Buxton tends to be cooler and much wetter than surrounding towns, with daytime temperature typically around 2 °C lower than Manchester. A Met Office weather station has collected climate data for the town since 1867, with digitised data from 1959 available online.[85] In June 1975, the town was hit by a freak snowstorm that stopped play during a cricket match.[86]

Demographics

In the 2011 census, Buxton was 98.3% White, 0.6% Asian, 0.2% Black, 0.8% Mixed/multiple.[87]

Famous Buxtonians

- Orlando Jewitt (1799 in Buxton – 1869), architectural wood-engraver

19th century

- Charles Chetwynd-Talbot, 20th Earl of Shrewsbury (1860–1921), styled Viscount Ingestre. In the early 1880s he ran a daily Greyhound (i.e. fast) coach service the 20 miles from Buxton Spa to his house at Alton Towers.

- Henry Guppy CBE (1861–1948), Librarian of the John Rylands Library in Manchester from 1899 to 1948, lived in Buxton.

- Vera Brittain (1893–1970), author[88] of Testament of Youth and mother of Shirley Williams, went to school in Buxton.

- Rear Admiral Leonard Warren Murray, CB, CBE (1896–1971 in Buxton),[89] senior officer of the Royal Canadian Navy who played a significant role in the Battle of the Atlantic

20th century

- Hugh Molson, Baron Molson, PC (1903–1991), Conservative politician[90] and MP for High Peak 1939–61

- Robert Stevenson, (1905 in Buxton – 1986), director[91] of Disney films including Mary Poppins

- John Pilkington Hudson (1910 in Buxton – 2007), horticultural scientist[92] and bomb disposal expert

- Herbert Eisner (1921–2011), British-German scientist[93] high-expansion fire fighting foam, playwright, schooled and lived in Buxton

- John Buxton Hilton (1921 in Buxton – 1986), crime writer[94]

- Angela Flanders (1927 in Buxton – 2016), perfumer[95]

- Marjorie Lynette Sigley (1928 in Buxton – 1997), artist, writer, actress,[96] teacher, choreographer, theatre director and TV producer

- Elizabeth Spriggs, (1929 in Buxton – 2008), character actress[97] with the Royal Shakespeare Company

- Sir Spencer Le Marchant (1931–1986), Conservative politician[90] and MP for High Peak 1970 to 1983

- Christopher Hawkins (born 1937), Conservative politician[90] and MP for High Peak 1983 to 1992

- Tim Brooke-Taylor OBE (1940–2020), comic actor[98] in The Goodies

- David Fallows (born 1945 in Buxton), musicologist[99] specializing in music of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance

- Dave Lee Travis (born 1945 in Buxton), former disc jockey,[100] radio and TV presenter

- Tom Levitt (born 1954), Labour politician[101] and MP High Peak 1997 to 2010

- Tony Marchington (1955 in Buxworth – 2011), biotechnology entrepreneur[102] and owner of the Flying Scotsman

- Lloyd Cole (born 1961 in Buxton), musician,[103] songwriter, frontman of Lloyd Cole and the Commotions

- Andrew Bingham (born 1962 in Buxton), Conservative politician[104] and MP for High Peak 2010 to 2017

- Dan Rhodes (born 1972), writer,[105] awarded the E. M. Forster Award in 2010, lives in Buxton

- Bruno Langley (born 1983), actor,[106] played Adam Mitchell in Doctor Who and Todd Grimshaw in Coronation Street, brought up in Buxton

- Lucy Spraggan (born 1991), musician[107] (folk, acoustic, hip hop pop), went to school in Buxton.

- Kieren Parker (born 2002), professional model,[108] political activist

Sport

- William Shipton (1861 in Buxton – 1941 in Buxton), cricketer,[109] 1884 to 1893, later solicitor in Buxton

- Fred Smith (1887 in Buxton – 1957), footballer before WWI, mainly for Macclesfield

- Bobby Blood (1894 in Harpur Hill – 1988 in Harpur Hill), footballer for Port Vale, West Brom and Stockport

- George Bailey (1906 in Buxton – 2000), steeplechaser,[110] competed at the 1932 Summer Olympics

- Frank Soo (1914 in Buxton – 1991), Stoke City F.C. footballer[111] (173 pro appearances) and first mixed-race professional to represent England

- John Tarrant (1932–1975), long-distance runner,[112] nicknamed "The Ghost Runner", lived in Buxton

- Mick Andrews (born 1944 in Buxton), former international[113] motorcycle trials rider

- Les Bradd (born 1947 in Buxton), former footballer,[114] over 580 pro appearances, all-time leading goalscorer for Notts County

- Carl Mason (born 1953 in Buxton), professional golfer[115]

- Mark Higgins (born 1958 in Buxton), former Everton, Bury and Stoke footballer, 265 pro appearances

- Lorraine Winstanley (born 1975), BDO darts player,[116] lives in Buxton

- Dean Winstanley (born 1981), BDO darts player,[117] lives in Buxton

- Ben Burgess (born 1981 in Buxton), Irish footballer,[118] played for Hull City F.C. and Blackpool F.C.

Literature

A series of four recent novels by Sarah Ward – In Bitter Chill (2015), A Deadly Thaw (2017), A Patient Fury (2018) and The Shrouded Path (2019) – feature the fictional town of Bampton, which the author states "is partly based on Buxton with its Georgian architecture, Bakewell, a well-heeled market town... and Cromford with its canal and fantastic industrial heritage."[119]

See also

- Buxton Hospital

- Cavendish Hospital

- Lightwood Reservoir

- Macclesfield group power stations

- Pubs and inns in Buxton

Sources

Notes

- ^ a b Alston, Cumbria also claims this, but lacks a regular market.

- ^ This is a photo of the cross before it was cut down in 2010. It has since been restored.

References

- ^ a b c "Buxton – in pictures" Archived 19 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC Radio Derby, March 2008, accessed 3 June 2013.

- ^ "towntwinning.org.uk". ww38.towntwinning.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ Buxton Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Key to English Place Names, Institute for Name Studies, University of Nottingham, accessed 12 May 2011

- ^ Robertson, William Henry (1859). A Guide To The Use Of The Buxton Waters. ISBN 9781318591060.

- ^ "Lismore Fields Buxton Spa History Ancient Settlement Civilisation". lismore-fields. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ About Buxton Archived 16 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, History of Buxton, accessed June 2009

- ^ a b Leach, John (1987). The Book of Buxton. Baracuda Books Limited. pp. 35–43, 124–125. ISBN 0 86023 286 7.

- ^ a b Dunn, Paul. "Great British Weekend: Buxton", Archived 22 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Sunday Times, 17 April 2010, accessed 20 September 2011

- ^ Historic England. "The Slopes, Buxton (1001456)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "De Mirabilibus Pecci: Being the Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire". www.wondersofthepeak.org.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Darwin, Charles, Frederick Burkhardt and Sydney Smith. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985 ISBN 0-521-25587-2

- ^ Railways of the Peak District, Blakemore & Mosley, 2003 ISBN 1-902827-09-0

- ^ "Canadian Red Cross Special Hospital Buxton 1915 – 1919". Buxton Museum and Art Gallery. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "BBC - World War One At Home, Buxton Pavilion Gardens, Derbyshire: Bridge Building Practice". BBC. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "R.A.F. Maintenance Unit 28 - Harpur Hill". Buxton Civic Association. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "The Beatles Bible - Live: Pavilion Gardens Ballroom, Buxton". The Beatles Bible. 6 April 1963. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Langham, Mike (2001). Buxton: A Peoples’ History. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing Ltd. p. 217-219. ISBN 1859360866.

- ^ Information about Buxton buildings Archived 25 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harrod, Tanya (2015). The real thing: essays on making in the modern world. London: Hyphen Press. pp. 134–137.

- ^ Lyttleton, Celia (1984). "In the Wake of William Morris & Co". Ritz Magazine: Art Inside. No. 5.

- ^ a b Hills, Ann (April 1987). "Buxton's New Landmark". Building Refurbishment.

- ^ "Natural Mineral Baths, Buxton" Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, BritishListedBuildings.co.uk, accessed 4 May 2012

- ^ "The Micrarium Story". www.micrariumenterprises.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008.

- ^ "Historic agreement paves way for Crescent development" Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, High Peak Borough Council, 2 April 2012

- ^ "Georgian hotel opens in Buxton 17 years after work begins". BBC. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Heritage Open Days to raise curtain on history of Buxton stage". www.buxtonadvertiser.co.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Pavilion Gardens, Buxton (Grade II*) (1000675)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Palace Hotel Buxton | Britannia Hotels". www.britanniahotels.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b Corbar cross rises again Archived 4 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Buxton Advertiser, 20 May 2011

- ^ Symbol of Suffering Archived 25 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Buxton Advertiser, 23 September 2010

- ^ "BUXTON CONSERVATION AREAS Character Appraisal" (PDF). High Peak Borough Council. April 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Buxton Festival 2010 Programme Archived 13 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Buxton Festival Website, September 2010

- ^ Buxton Festival Archived 17 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine Buxton Opera House Website, September 2010

- ^ Christiansen, Rupert. "The Buxton Festival: aiming for peak performance" Archived 1 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Telegraph Online, July 2010

- ^ Canning, Hugh. Buxton Festival Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine,Times Online, July 2008

- ^ "About Us". Buxton Festival Fringe. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Party to celebrate bumper Buxton Festival Fringe!". Buxton Festival Fringe. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Four four time" Archived 21 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Buxton Opera House website, September 2010

- ^ Chalmers, Graham. "Harrogate wins topsy-turvy battle over G&S Festival" Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Wetherby News, 5 June 2014

- ^ Whats On Archived 21 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Buxton Opera House, September 2010

- ^ "The Pavilion Arts Centre" Archived 15 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Pavilion Gardens website, September 2010

- ^ Woolman, Natalie. "Buxton Opera House to open new Pavilion arts venue" Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Stage, 7 September 2010

- ^ "Buxton Museum and Art Gallery" Archived 20 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Derbyshire County Council

- ^ "Fairs & Events" Archived 9 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Pavilion Gardens website

- ^ "Buxton Well Dressing Festival". Buxton Well Dressing Festival website. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ a b High Peak Profile Archived 26 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine, High Peak Borough Council, September 2010

- ^ "Buxton Water" Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, official website, March 2012

- ^ "About Us". www.pottersofbuxton.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015.

- ^ "BLF Buxton Lime Firms". www.derbyshireheritage.co.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Quarries visible as large white areas in satellite image, Google Maps, September 2010

- ^ Superquarries: Tunstead Archived 6 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, British Geological Survey website, September 2010

- ^ "Buxton Lime" Archived 23 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Tarmac company website, September 2010

- ^ Hailstone, Laura. "Lomas Distribution consolidates sites with new depot" Archived 7 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Commercialmotor.com, 1 July 2008, accessed 29 August 2012

- ^ About HSL Archived 30 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, HSL Website, September 2010

- ^ Health & Safety Laboratory Archived 1 September 2011 at archive.today, Northern Defence Industries Website

- ^ "St. Thomas More Catholic School" Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 February 2014

- ^ "Buxton Junior School" Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 February 2014

- ^ "St. Anne's Catholic Primary School" Archived 25 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 February 2014

- ^ "Harpur Hill Primary School" Archived 17 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 6 July 2017

- ^ "Buxton Infant School" Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 February 2014

- ^ "Schools and Colleges Near Buxton, Derbyshire" Archived 8 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 February 2014

- ^ "Buxton Raceway". Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "About Us" Archived 28 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Buxton Raceway website

- ^ "Speedway in Derbyshire", Archived 18 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine You and Yesterday, accessed on 16 December 2007

- ^ Hubbert, Neil. "Victory for the Hitmen", Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Buxton Advertiser, 2 August 2007

- ^ "BriSCA F2 World Championship 2019". buxtonraceway.com. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Buxton Cricket Club". archive.org. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Buxton Rugby Club Archived 8 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 10 December 2011

- ^ "Buxton Hockey Club – Website for Buxton Hockey Club". www.buxtonhockeyclub.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Cavendish Golf Club - Award-winning golf club in Buxton, Derbyshire". Cavendish Golf Club. Archived from the original on 6 November 2008.

- ^ "Home". Buxton and High Peak Golf Club. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

- ^ Warren, Daniel and Graham Warren. High over Buxton: A Boulderer's Guide, Raven Rock Books (2003) ISBN 0-9530352-1-2

- ^ Gibson, Gary. From Horseshoe to Harpur Hill, BMC (2004) ISBN 0-903908-72-7

- ^ "Kaleidoscope" Archived 8 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Buxton Opera House, accessed 12 May 2011

- ^ "home". 2517sqn.org.uk.

- ^ United Grand Lodge of England (2006) Directory of Lodges and Chapters London

- ^ National Rail Departures Board Archived 10 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved Feb 2017

- ^ High Peak Skyline 199 service Archived 11 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved Feb 2017

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) High Peak Routes list] Retrieved Feb 2017 - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Staffs CC Leek and Moorlands bus route maps and timetables] Retrieved Feb 2017 - ^ "Timetable Information" Archived 15 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, High Peak Buses, accessed 1 July 2012

- ^ "Buxton". Peak District Online. Peak District Online. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Oldham, T. "History of Poole's Cavern" Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Showcaves.com (2002)

- ^ elevationmap.net. "Town Hall Buxton Sk17 Uk on the Elevation Map. Topographic Map of Town Hall Buxton Sk17 Uk". elevationmap.net. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- ^ Hilton, Michael. "The Buxton Meteorological Station: A Brief History". BuxtonWeather.com. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Francis, Tony. "June Snow" Archived 4 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph, 22 June 2005

- ^ "United Kingdom: East of England (Local Authority Districts and Wards) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ Biography and List of Works at Litweb website archive retrieved January 2018

- ^ Canadian Encyclopedia – Murray, Leonard Warren Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ a b c Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs Archived 9 January 2012 at Wikiwix retrieved January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 15 February 2004 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 201

- ^ The Guardian, 8 February 2008, Obituary, John Hudson Archived 5 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Telegraph obituary, 28 Jul 2011, Herbert Eisner Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Curtis Brown website, literary and talent agency Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ "Angela Flanders, perfumer – obituary". Daily Telegraph. 22 May 2016. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 17 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 26 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Research page, University of Manchester Archived 21 December 2015 at Wikiwix retrieved January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ TheyWorkForYou website, Tom Levitt MP Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Flying Scotsman Steams into Derbyshire, aboutderbyshire.co.uk, June 23, 2007 Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Lloyd Cole at AllMusic website, profile Archived 14 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ TheyWorkForYou website, profile Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ A writer's life:Dan Rhodes, The Telegraph, 22 Mar 2003 Archived 24 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ IMDb Database Archived 17 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ http://modelmode.amvp.co.uk/catalog/search

- ^ Wisden Obituaries in 1941 Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ George Bailey, Olympics at Sports-Reference.com Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ The Wanderer–Just who was Frank Soo, The Football Pink Archived 21 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Amazing Story of the Ghost Runner[permanent dead link], Derby Telegraph, 11 December 2011, Retrieved 14 September 2015

- ^ MickAndrews.net website Archived 23 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Player profile Football_england.com archive retrieved January 2018

- ^ "Carl Mason" Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Player biographies, The PGA European Tour, accessed 1 July 2012

- ^ Player profile on Lorraine Winstanley from Dartsdatabase Archived 15 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Player profile on Dean Winstanley from Dartsdatabase Archived 18 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ SoccerBase Database Archived 27 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 2018

- ^ Faber publications. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

Further reading

- W. Bemrose. Guide to Buxton and Neighbourhood, Bemrose & Sons (London, 1869).

- Black's Guide to Buxton and the Peak country of Derbyshire, A. and C. Black, 1898

- Aitken, Tom. One Hundred & One Beautiful Towns in Great Britain, Rizzoli, 2008

- Gifford-Bennet, Robert Ottiwell (2009) [1892]. Buxton and its Medicinal Waters. London: John Heywood.

- Langham, Mike. Buxton: A People's History, Carnegie Publishing, 2001

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Buxton Newsdesk, Latest Buxton and High Peak News

- Visit Buxton.co.uk

- Explore Buxton