Selimiye Mosque, Edirne

| Selimiye Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Edirne, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°40′41″N 26°33′34″E / 41.67806°N 26.55944°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Mimar Sinan |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Ottoman architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 1568 |

| Completed | 1574 |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 43 m (141 ft) |

| Dome dia. (outer) | 31.2 m (102 ft) |

| Minaret(s) | 4 |

| Minaret height | 83 m (272 ft)[1] |

| Materials | cut stone, marble |

| Official name: Selimiye Mosque and its Social Complex | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 2011 (35th session) |

| Reference no. | 1366 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Selimiye Mosque (Template:Lang-tr) is an Ottoman imperial mosque, which is located in the city of Edirne (formerly Adrianople), Turkey. The mosque was commissioned by Sultan Selim II, and was built by the imperial architect Mimar Sinan between 1568 and 1575.[2] It was considered by Sinan to be his masterpiece and is one of the highest achievements of Islamic architecture and Ottoman architecture.

It was added as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.

Description

This grand mosque stands at the center of a külliye (complex of a hospital, school, library and/or baths around a mosque) which comprises a medrese (Islamic academy teaches both Islamic and scientific lessons), a dar-ül hadis (Al-Hadith school), a timekeeper's room and an arasta (row of shops). In this mosque Sinan employed an octagonal supporting system that is created through eight pillars incised in a square shell of walls. The four semi domes at the corners of the square behind the arches that spring from the pillars, are intermediary sections between the huge encompassing dome (31.25 metres (102.5 feet) diameter with spherical profile) and the walls.

While conventional mosques were limited by a segmented interior, Sinan's effort at Edirne was a structure that made it possible to see the mihrab from any location within the mosque. Surrounded by four tall minarets, the Mosque of Selim II has a grand dome atop it. Around the rest of the mosque were many additions: libraries, schools, hospices, baths, soup kitchens for the poor, markets, hospitals, and a cemetery. These annexes were aligned axially and grouped, if possible. In front of the mosque sits a rectangular court with an area equal to that of the mosque. The innovation however, comes not in the size of the building, but from the organization of its interior. The mihrab is pushed back into an apse-like alcove with a space with enough depth to allow for window illumination from three sides. This has the effect of making the tile panels of its lower walls sparkle with natural light. The amalgamation of the main hall forms a fused octagon with the dome-covered square. Formed by eight massive dome supports, the octagon is pierced by four half dome covered corners of the square. The beauty resulting from the conformity of geometric shapes engulfed in each other was the culmination of Sinan's lifelong search for a unified interior space.

At the Bulgarian siege of Edirne in 1913, the dome of the mosque was hit by Bulgarian artillery. Owing to the dome's extremely sturdy construction, the mosque survived the assault with only minor damage. On Mustafa Kemal Pasha's order, it has not been restored since then, to serve as a warning for future generations.[citation needed] Some damage can be seen on the image of the dome above, at and near the dark red calligraph to the immediate left of the central blue area.

In the year 1865 Baha'u'llah,[3] The founder of The Baha'i Faith, arrived with his family to Edirne as prisoner of the Ottoman empire and resided in a house near Selimiye Mosque,[4] which he visited often until 1868. It was at Selimiye mosque[5] where He was supposed to have an open debate with Mirza Yahya, an important historical event distinguishing the Baha'i faith from the covenant breakers guided by Mirza Yahia.

Architecture

Exterior

Selimiye Mosque was built at the peak of Ottoman military and cultural power. As the empire started to grow, the emperor had found an immediate urge to centralize the city. Sinan was asked to help to construct the Selimiye Mosque, making the mosque distinctive and served the purpose of centralizing the city.[6]

Like all other Ottoman mosques in the earlier periods, the Selimiye Mosque had a multitude of little domes and half domes. However, the limit in building Selimiye was to viewing the mosque as a single unit from inside or outside rather than separate masses. Sinan believed that building a single dome would be the only resolution to achieve this. Hence, he ambitiously decided to replace the busy confused domes in the center with an enormous one. The author of Other Colors, Orhan Pamuk mentioned that he saw a connection between the wish of the central dome and the centralizing political and economic changes made by the empire, but the idea was later objected by another book written by Sinan’s friend, Sai, claiming that Sinan had taken his inspiration from Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia.[6] Perhaps lending more credence to this idea is a quote by Sinan in which he claims that he has built a taller dome than Hagia Sophia: "In this mosque...I [have] erected a dome six cubits higher and four cubits wider than the dome of Hagia Sophia."[7]

In order to accentuate and draw attention to the centralized structure of the mosque, the traditional placement of different sized minarets was abandoned from the design as Sinan believed that cascade of smaller domes and half-domes used earlier would play down the gigantic single-shell dome. Besides, four identical minarets were planted at each corner of the marble forecourt to enforce attention on the surrounded central dome. The four vertically fluted symmetrical minarets amplify the upward thrust, shooting towards the sky like rockets from each corner of the mosque, according to Ottoman scholar Gulru Necipoglu. With the great dome rising subtlety from the center, it had harmoniously interplayed with the half domes, weight towers, and buttresses crowded around it. It was believed that the circular architecture was to affirm the oneness in humanity and called out the simple ideology of circle of life. The visible and invisible symmetries that were called out from the exterior and interior of the mosque was to evoke God’s perfection through the plain and powerful structure of the dome and the bare stone.

Interior

The interior of the mosque received great recognitions from its clean, spare lines in the structure itself. With the monumental exteriors proclaiming the wealth and power of the Ottoman Empire, the plain symmetrical interiors reminded the sultans should always provide a humble and faithful heart in order to connect and communicate with God. To enter, it was to forget the power, determination, wealth and technical mastery of the Ottoman Empire. Lights were seeped through multitude of tiny windows, and the interchanging of the weak light and dark was interpreted as the insignificance of humanity. The Selimiye Mosque did not only amaze the public with the extravagant symmetrical exterior, it had also astonished the people with the plain symmetrical interior for it had summarized all Ottoman architectural thinking in one simple pure form.

The mosque was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 10,000 lira banknotes of 1982-1995.[8] The mosque, together with its külliye, was included on UNESCO's World Heritage List in 2011.

Gallery

-

Dome and Minarets

-

Interior view of the central dome

-

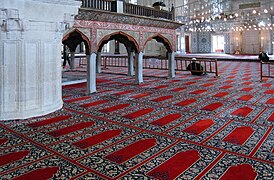

Selimiye Mosque interior

-

Ottoman period tombstones and a museum near the mosque.

-

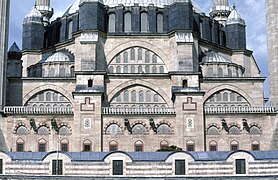

Selimiye, central part from the south

-

Selimiye, detail of south side

-

Selimiye courtyard

-

Selimiye, mihrab area

-

Selimiye, tiles at mihrab

-

Selimiye, dome

-

Selimiye, interior

-

exterior

See also

References

2a. Peter Francopan, The Silk Roads, page 232… (1564 - 1574) Selimiye mosque was built

- ^ Architecture, Jonathan Glancey, page 207, 2006

- ^ Kiuiper, Kathleen (2009). Islamic Art, Literature, and Culture. Rosen Education Service. pp. 201. ISBN 978-1-61530-019-8.

- ^ "Bahá'u'lláh", Wikipedia, 2019-06-03, retrieved 2019-06-12

- ^ The Bábí and Bahá'í religions 1844-1944 : some contemporary western accounts. Momen, Moojan. Oxford: G. Ronald. 1981. ISBN 0853981027. OCLC 10777195.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Momen, Moojan (1981). The Bábí and Bahá'í religions 1844-1944: some contemporary western accounts. Oxford: G. Ronald. ISBN 9780853981022. OCLC 10777195.

- ^ a b Pamuk, Orhan (2007). Other Colors. Alfred A. Knoff. ISBN 978-0-307-26675-0.

- ^ Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995-01-01). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300064659.

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-03 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group - Ten Thousand Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, II. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, III. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine & IV. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

External links

- World Heritage Sites in Turkey

- Religious buildings and structures completed in 1574

- Mimar Sinan buildings

- Ottoman architecture in Edirne

- Ottoman mosques in Edirne

- Religious buildings and structures with domes

- Mosques in Edirne

- Landmarks in Turkey

- Tourist attractions in Edirne

- 16th-century mosques

- Historic sites in Turkey