A Fistful of Dollars

| A Fistful of Dollars | |

|---|---|

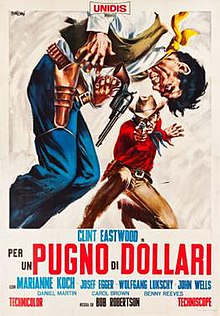

Italian theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sergio Leone |

| Based on | Yojimbo by Akira Kurosawa Ryūzō Kikushima (both uncredited) |

| Produced by | Arrigo Colombo Giorgio Papi[1] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Massimo Dallamano[1] |

| Edited by | Roberto Cinquini[1] |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Unidis |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 99 minutes[1] |

| Countries | |

| Languages | Italian English |

| Budget | $200,000–225,000[2] |

| Box office | $4,375,000 (Italy)[3] $14.5 million (US and Canada) |

A Fistful of Dollars (Template:Lang-it[1] titled on-screen as Fistful of Dollars) is a 1964 Spaghetti Western film directed by Sergio Leone and starring Clint Eastwood in his first leading role, alongside John Wells, Marianne Koch, W. Lukschy, S. Rupp, Jose Calvo, Antonio Prieto, and Joe Edger.[4] The film, an international co-production between Italy, West Germany, and Spain, was filmed on a low budget (reported to be $200,000), and Eastwood was paid $15,000 for his role.[5]

Released in Italy in 1964 and then in the United States in 1967, it initiated the popularity of the Spaghetti Western genre. It was followed by For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, also starring Eastwood. Collectively, the films are known as the "Dollars Trilogy", or the "Man with No Name Trilogy" after the United Artists publicity campaign referred to Eastwood's character in all three films as the "Man with No Name". All three films were later released in sequence in the United States in 1967, catapulting Eastwood into stardom.[6] The film has been identified as an unofficial remake of the Akira Kurosawa film Yojimbo (1961), which resulted in a successful lawsuit by Toho, Yojimbo's production company.

As few Spaghetti Westerns had yet been released in the United States, many of the European cast and crew took on American-sounding stage names. These included Leone himself ("Bob Robertson"), Gian Maria Volonté ("Johnny Wels"), and composer Ennio Morricone ("Dan Savio"). A Fistful of Dollars was shot in Spain, mostly near Hoyo de Manzanares[7] close to Madrid, but also (like its two sequels) in the Tabernas Desert and in the Cabo de Gata-Níjar Natural Park, both in the province of Almería.

Plot

An unnamed stranger[N 1] arrives at the little town of San Miguel, on the Mexico–United States border. Silvanito, the town's innkeeper, tells the Stranger about a feud between two smuggler families vying to gain control of the town: the Rojo brothers (Don Miguel, Esteban and Ramón), and the family comprising town sheriff John Baxter, his matriarchal wife Consuelo, and their son Antonio. The Stranger (in order to make money) decides to play these families against each other. He demonstrates his speed and accuracy with his gun, to both sides, by shooting with ease the four men who insulted him as he entered town.

The Stranger seizes an opportunity when he sees the Rojos massacre a detachment of Mexican soldiers who were escorting a chest of gold (which they had planned to exchange for a shipment of new rifles). He takes two of the dead bodies to a nearby cemetery and sells information to each of two groups, saying that two Mexican soldiers survived the attack. Each faction races to the cemetery, the Baxters to get the supposed survivors to testify against the Rojos and the Rojos to silence them; they engage in a gunfight, with Ramón appearing to kill the supposed survivors and Esteban capturing Antonio Baxter.

The Stranger then tells Marisol to go to Ramón, and Julio to take Jesús home. He learns from Silvanito that Ramón had framed Julio as cheating during a card game, and taken Marisol as a prisoner living with him. That night, while the Rojos are celebrating, the Stranger rides out and frees Marisol, shooting the guards and wrecking the house in which she is being held, creating an appearance of an attack by the Baxters. He gives money to Marisol, urging her and her family to leave the town.

When the Rojos discover the Stranger has freed Marisol, they capture and torture him; nevertheless, he escapes them. Believing he is protected by the Baxters, the Rojos set fire to the Baxter home, massacring them as they flee the burning building. Ramón kills John and Antonio Baxter, after pretending to spare them. Consuelo, John Baxter's wife, appears and curses the Rojos for killing these unarmed family members; she is shot to death by Esteban.

With help from Piripero, the local coffin-maker, the Stranger escapes town, hiding in a coffin. He convalesces within a nearby mine, but when Piripero tells him that Silvanito has been captured, the Stranger returns to town, to confront the Rojos. With a steel chest-plate hidden beneath his poncho, he taunts Ramón to "aim for the heart" as Ramón's shots bounce off, and Ramón exhausts his Winchester rifle.

The Stranger shoots that weapon from Ramón's hand and kills Don Miguel, Rubio and the other Rojo men standing nearby. He then uses the last bullet in his gun to free Silvanito, tied hanging from a post. After challenging Ramón to reload his rifle, faster than he can reload his own revolver, the Stranger shoots and kills Ramón. Esteban Rojo aims for the Stranger's back from a nearby building, but is shot dead by Silvanito. The Stranger bids farewell, and rides away from town in the film's last shot.

Cast

- Clint Eastwood as "Joe", the Man with No Name

- Marianne Koch as Marisol

- Johnny Wels as Ramón Rojo

- W. Lukschy as Sheriff John Baxter

- S. Rupp as Esteban Rojo

- Joe Edger as Piripero

- Antonio Prieto as Don Miguel Rojo (Don Benito Rojo in the Italian version)

- Jose Calvo as Silvanito

- Margherita Lozano as Consuelo Baxter

- Daniel Martín as Julio

- Benny Reeves as Rubio

- Mario Brega as Chico

- Carol Brown as Antonio Baxter

- Aldo Sambreli as Manolo

Additional cast members include Raf Baldassarre as Juan De Dios, Nino del Arco as Jesus, Enrique Santiago as Fausto, Umberto Spadaro as Miguel, Fernando Sánchez Polack as Vicente, and José Riesgo as the Mexican cavalry captain. Members of the Baxter gang include Luis Barboo, Frank Braña, Antonio Molino Rojo, Lorenzo Robledo, and William R. Thompkins. Members of the Rojo gang include José Canalejas, Álvaro de Luna, Nazzareno Natale, and Antonio Pica.

Development

A Fistful of Dollars originally was called Il Magnifico Straniero (The Magnificent Stranger) before the title was changed to A Fistful of Dollars.[8] The film was at first intended by Leone to reinvent the western genre in Italy. In his opinion, the American westerns of the mid- to late-1950s had become stagnant, overly preachy and not believable. Despite the fact that even Hollywood began to gear down production of such films, Leone knew that there was still a significant market in Europe for westerns. He observed that Italian audiences laughed at the stock conventions of both American westerns and the pastiche work of Italian directors working behind pseudonyms. His approach was to take the grammar of Italian film and to transpose it into a western setting.[citation needed]

The production and development of A Fistful of Dollars from anecdotes was described by Italian film historian Roberto Curti as both contradictory and difficult to decipher.[9] Following the release of Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo in 1963 in Italy, Sergio Corbucci has claimed he told Leone to make the film after viewing the film with friends and suggesting it to Enzo Barboni.[9] Tonino Valerii alternatively said that Barboni and Stelvio Massi met Leone outside a theater in Rome where they had seen Yojimbo, suggesting to Leone that it would make a good Western.[9] Actor and friend of Leone Mimmo Palmara told a similar story to Valerii, saying that Barboni had told about Yojimbo to him and he would see it the next day with Leone and his wife Carla.[9][10] Following their screening, they discussed how it could be applied into a Western setting.[10]

Adriano Bolzoni stated in 1978 that he had the idea of making Yojimbo into a Western and brought the idea to Franco Palaggi, who sent Bolzoni to watch the film and take notes on it with Duccio Tessari.[10] Bolzoni then said both he and Tessari wrote a first draft which then moved on to Leone noting that Tessari wrote the majority of the script.[10]

Fernando di Leo also claimed authorship to the script noting that both A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More were written by him and Tessari and not Luciano Vincenzoni.[10] Di Leo claimed that after Leone had the idea for the film, Tessari wrote the script and he gave him a hand.[10] Di Leo would repeat this story in a later interview saying that he was at the first meetings between Tessari and Leone discussing what kind of film to make from Yojimbo.[10] Di Leo noted that Leone did not like the first draft of the script which led to him drastically re-writing it with Tessari.[10] Production papers for the film credit Spanish and German writers, but these were added on to play into co-production standards during this period in filmmaking in order to get more financing from the Spanish and West German companies.[10] Leone himself would suggest that he wrote the entire screenplay himself based on Tessari's treatment.[10]

Eastwood was not the first actor approached to play the main character. Originally, Sergio Leone intended Henry Fonda to play the "Man with No Name".[11] However, the production company could not afford to employ a major Hollywood star. Next, Leone offered Charles Bronson the part. He, too, declined, arguing that the script was bad. Both Fonda and Bronson would later star in Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Other actors who turned the role down were Henry Silva, Rory Calhoun, Tony Russel,[12] Steve Reeves, Ty Hardin, and James Coburn.[13][14][15][16] Leone then turned his attention to Richard Harrison, an expatriate American actor who had recently starred in the very first Italian western, Duello nel Texas. Harrison, however, had not been impressed with his experience on that previous film and refused. The producers later presented a list of available, lesser-known American actors and asked Harrison for advice. Harrison suggested Eastwood, who he knew could play a cowboy convincingly.[17] Harrison later stated, "Maybe my greatest contribution to cinema was not doing A Fistful of Dollars and recommending Clint for the part."[18] Eastwood later spoke about transitioning from a television western to A Fistful of Dollars: "In Rawhide, I did get awfully tired of playing the conventional white hat ... the hero who kisses old ladies and dogs and was kind to everybody. I decided it was time to be an anti-hero."[19]

A Fistful of Dollars was an Italian/German/Spanish co-production, so there was a significant language barrier on set. Leone did not speak English,[20] and Eastwood communicated with the Italian cast and crew mostly through actor and stuntman Benito Stefanelli, who also acted as an uncredited interpreter for the production and would later appear in Leone's other pictures. Similar to other Italian films shot at the time, all footage was filmed silent, and the dialogue and sound effects were dubbed over in post-production.[21] For the Italian version of the film, Eastwood was dubbed by stage and screen actor Enrico Maria Salerno, whose "sinister" rendition of the Man with No Name's voice contrasted with Eastwood's cocksure and darkly humorous interpretation.[22]

Visual style

A Fistful of Dollars became the first film to exhibit Leone's famously distinctive style of visual direction. This was influenced by both John Ford's cinematic landscaping and the Japanese method of direction perfected by Akira Kurosawa. Leone wanted an operatic feel to his western, and so there are many examples of extreme close-ups on the faces of different characters, functioning like arias in a traditional opera. The rhythm, emotion, and communication within scenes can be attributed to Leone's meticulous framing of his close-ups.[23] This is quite different from Hollywood's use of close-ups that used them as reaction shots, usually to a line of dialogue that had just been spoken. Leone's close-ups are more akin to portraits, often lit with Renaissance-type lighting effects, and are considered by some as pieces of design in their own right.[24]

Eastwood was instrumental in creating the Man with No Name's distinctive visual style. He bought black jeans from a sport shop on Hollywood Boulevard, the hat came from a Santa Monica wardrobe firm, and the trademark cigars from a Beverly Hills store.[25] He also brought props from Rawhide including a Cobra-handled Colt, a gunbelt, and spurs.[26] The poncho was acquired in Spain.[27] It was Leone and costume designer Carlo Simi who decided on the Spanish poncho for the Man with No Name.[26] On the anniversary DVD for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, it was said that while Eastwood himself is a non-smoker, he felt that the foul taste of the cigar in his mouth put him in the right frame of mind for his character. Leone reportedly took to Eastwood's distinctive style quickly and commented that, "More than an actor, I needed a mask, and Eastwood, at that time, only had two expressions: with hat and no hat."[28]

Title design

Iginio Lardani created the film's title design.[29]

Soundtrack

The film's music was written by Ennio Morricone, credited as Dan Savio.

Leone requested Morricone to write a theme that would be similar to Dimitri Tiomkin's El Degüello (used in Rio Bravo, 1959). Although the two themes are similar, Morricone states that he used a lullaby he had composed before and developed the theme from that. He adds that what makes the two themes similar is the execution, not the arrangement.[30]

In 1962 expatriate American folk singer Peter Tevis recorded a version of Woody Guthrie's "Pastures of Plenty" that was arranged by Morricone. During a conference with Morricone over the music in the film a recording of Tevis's Pastures of Plenty was played. Sergio Leone said "That's it"[31] with Tevis claiming the tune and musical arrangements were copied for the music for the opening titles "Titoli".

"Some of the music was written before the film, which is unusual. Leone's films were made like that because he wanted the music to be an important part of it, and he often kept the scenes longer simply because he didn't want the music to end. That's why the films are so slow—because of the music."[32]

Though not used in the completed film, Peter Tevis recorded lyrics to Morricone's main theme for the film. As a movie tie-in to the American release, United Artists Records released a different set of lyrics to Morricone's theme called Restless One by Little Anthony and the Imperials.

Tracks (2006 GDM version)[33]

- Titoli 2:58

- Quasi morto 1:40

- Musica sospesa 1:02

- Square dance 1:36

- Ramon 1:05

- Consuelo Baxter 1:18

- Doppi giochi 1:41

- Per un pugno di dollari (1) 1:26

- Scambio di prigionieri 0:55

- Cavalcata 3:29

- L'inseguimento 2:25

- Tortura 9:31

- Alla ricerca dell'evaso 1:22

- Senza pietà 2:08

- La reazione 2:36

- Per un pugno di dollari (2) 1:49

- Per un pugno di dollari (finale) 1:09

Release and reception

Box office

Promoting A Fistful of Dollars was difficult, because no major distributor wanted to take a chance on a faux-Western and an unknown director. The film ended up being released in Italy on 12 September 1964,[1] which was typically the worst month for sales.

Despite the initial negative reviews from Italian critics, at a grassroots level its popularity spread and over the film's theatrical release, grossing 2.7 billion lire (US$4.4 million) in Italy, more than any other Italian film up to that point,[34] from admissions of 14,797,275 ticket sales.[35][36] The film sold 4,383,331 tickets in France and 3,281,990 tickets in Spain,[37] for a total of 22,462,596 tickets sold in Europe.

The release of the film was delayed in the United States, because distributors feared being sued by Kurosawa. As a result, it was not shown in American cinemas until 18 January 1967.[38] The film grossed $4.5 million for the year.[34] In 1969, it was re-released, earning $1.2 million in theatrical rentals.[39] It eventually grossed $14.5 million in the United States and Canada.[40] This adds up to $18.9 million grossed in Italy and North America.

Critical response

The film was initially shunned by the Italian critics, who gave it extremely negative reviews. Some American critics felt differently from their Italian counterparts, with Variety praising it as having "a James Bondian vigor and tongue-in-cheek approach that was sure to capture both sophisticates and average cinema patrons".[38]

Upon the film's American release in 1967, both Philip French and Bosley Crowther were unimpressed with the film itself. Critic Philip French of The Observer stated:

"The calculated sadism of the film would be offensive were it not for the neutralising laughter aroused by the ludicrousness of the whole exercise. If one didn't know the actual provenance of the film, one would guess that it was a private movie made by a group of rich European Western fans at a dude ranch... A Fistful of Dollars looks awful, has a flat dead soundtrack, and is totally devoid of human feeling."[41]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times treated the film not as pastiche, but as camp-parody, stating that nearly every Western cliche could be found in this "egregiously synthetic but engrossingly morbid, violent film". He went on to patronize Eastwood's performance, stating: "He is simply another fabrication of a personality, half cowboy and half gangster, going through the ritualistic postures and exercises of each... He is a morbid, amusing, campy fraud".[42]

When the film was released on the televised network ABC on 23 February 1975,[43] a four and a half minute prolog was added to the film to contextualize the character and justify the violence. Written and directed by Monte Hellman, it featured an unidentified official (Harry Dean Stanton) offering the Man With No Name a chance at a pardon in exchange for cleaning up the mess in San Miguel. Close-ups of Eastwood's face from archival footage are inserted into the scene alongside Stanton's performance.[44][45] This prolog opened television presentations for a few years before disappearing; it reappeared on the Special Edition DVD and the more recent Blu-ray, along with an interview with Monte Hellman about its making.[46][47]

The retrospective reception of A Fistful of Dollars has been much more positive, noting it as a hugely influential film in regards to the rejuvenation of the Western genre. Howard Hughes, in his 2012 book Once Upon a Time in the Italian West, reflected by stating: "American and British critics largely chose to ignore Fistful's release, few recognising its satirical humour or groundbreaking style, preferring to trash the shoddy production values...".[48]

A Fistful of Dollars has achieved a 98% approval rating out of 48 critical reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 8.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "With Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo as his template, Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars helped define a new era for the Western and usher in its most iconic star, Clint Eastwood." It was also placed 8th on the site's 'Top 100 Westerns'.[49]

The 67th Cannes Film Festival, held in 2014, celebrated the "50th anniversary of the birth of the Spaghetti Western... by showing A Fistful of Dollars".[50] Quentin Tarantino, prior to hosting the event, in a press-release described the film as "the greatest achievement in the history of Cinema".[50]

Legal dispute

The film was effectively an unofficial and unlicensed remake of Akira Kurosawa's 1961 film Yojimbo (written by Kurosawa and Ryūzō Kikushima), lifting traditional themes and character tropes usually typified within a Jidaigeki film. Kurosawa insisted that Leone had made "a fine movie, but it was my movie."[51] Leone ignored the resulting lawsuit, but eventually settled out of court, reportedly for 15% of the worldwide receipts of A Fistful of Dollars and over $100,000.[52][53]

British critic Sir Christopher Frayling identifies three principal sources for A Fistful of Dollars: "Partly derived from Kurosawa's samurai film Yojimbo, partly from Dashiell Hammett's novel Red Harvest (1929), but most of all from Carlo Goldoni's eighteenth-century play Servant of Two Masters."[54] Leone has cited these alternate sources in his defense. He claims a thematic debt, for both Fistful and Yojimbo, to Carlo Goldoni's Servant of Two Masters—the basic premise of the protagonist playing two camps against each other. Leone asserted that this rooted the origination of Fistful/Yojimbo in European, and specifically Italian, culture. The Servant of Two Masters plot can also be seen in Hammett's detective novel Red Harvest. The Continental Op hero of the novel is, significantly, a man without a name. Leone himself believed that Red Harvest had influenced Yojimbo: "Kurosawa's Yojimbo was inspired by an American novel of the serie-noire so I was really taking the story back home again."[55]

Leone also referenced numerous American Westerns in the film, most notably Shane[56] (1953) and My Darling Clementine (1946) which differs from Yojimbo.

Digital restoration

In 2014, the film was digitally restored by Cineteca di Bologna and Unidis Jolly Film for its Blu-ray debut and 50th anniversary. Frame-by-frame digital restoration by Prasad Corporation removed dirt, tears, scratches and other defects.[57][58] The directorial credit for Leone, which replaced the "Bob Robertson" card years ago, has been retained, but otherwise, the original credits (with pseudonyms, including "Dan Savio" for Morricone) remain the same.

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Curti, Roberto (2016). Tonino Valerii: The Films. McFarland. p. 192. ISBN 978-1476626185.

- ^ Sources that refer to the budget of Fistful of Dollars include:

- "Per un pugno di dollari - Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- "Sergio Leone Factoids". Fistful of Leone. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Hicks, Christopher (25 January 1990). "Eastwood Remembers 'Fistful of Dollars' Director". Deseret News. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Top Italian Film Grossers". Variety. 11 October 1967. p. 33.

- ^ Variety film review; 18 November 1964, page 22.

- ^ "Ennio Morricone" by Jerry McCulley, essay in the 1995 CD "The Ennio Morricone Anthology", Rhino DRC2-1237

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (2015). Clint: The Life and Legend (updated and revised). New York: OR Books. ISBN 978-1-939293-96-1.

- ^ Caldito, Angel (3 September 2008). "Los primeros decorados del Oeste en España, en Hoyo de Manzanares" (in Spanish). Historias Matritenses. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Ciardiello, Joe (28 June 2014). "A 'Fistful' of cinematic history". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c d Curti, Roberto (2016). Tonino Valerii: The Films. McFarland. p. 25. ISBN 978-1476626185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Curti, Roberto (2016). Tonino Valerii: The Films. McFarland. p. 26. ISBN 978-1476626185.

- ^ Frayling 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Barnum, Michael The Wild Wild Interview: Tony Russel Our Man On Gamma 1 Video Watchdog No. 128 Dec/Feb 2007

- ^ Hughes, p.3

- ^ "Steve Reeves Interview Pt 2". drkrm. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Carrerowbonanza, Jack (11 June 2004). "Relive the thrilling days of the Old West in film". Tahoe Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Williams, Tony (October 2003). "A Fistful of Dollars". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Richard Harrison sur Nanarland TV" (in French). Nanarland TV. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Entretien avec Richard Harrison (English version)". Nanarland. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Hughes, p.4

- ^ "More Than A Fistful of Interview: Christopher Frayling on Sergio Leone". Fistful of Leone. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Munn, p. 48

- ^ Christopher Frayling, For a Few Dollars More audio commentary. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Frayling 2006. p. 100

- ^ Sir Christopher Frayling, A Fistful of Dollars audio commentary (Blu-ray version). Retrieved on 15 September 2014.

- ^ Munn, p. 46

- ^ a b Hughes, p.5

- ^ Munn, p. 47

- ^ Mininni, Francesco. "Intervista: Sergio Leone". Cinema Del Silenzio (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "A Fistful of Dollars title sequence". Watch the Titles. Submarine Channel. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Viva Leone!. BBC (Documentary). 1989.

- ^ Cumbow, Robert C. The Films of Sergio Leone Scarecrow Press, 15 February 2008

- ^ "Q&A - Ennio Morricone". The Observer. Guardian News and Media. 18 March 2007. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "GDM Music S.r.l." www.gdmmusic.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ a b Hughes, p.7

- ^ "La classifica dei film più visti di sempre al cinema in Italia". movieplayer.it. 25 January 2016. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Monaco, Eitel (11 October 1967). "Italian Films Succeed Alone And With U.S.A.". Variety. p. 29.

- ^ "Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars) (1964)". JP's Box-Office (in French). Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ a b McGillagan (1999), p.144

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1969". Variety. 7 January 1970.

- ^ "A Fistful of Dollars (1967)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ French, Philip (11 June 1967). "Under Western disguise". The Observer. Guardian News and Media. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (2 February 1967). "Screen: 'A Fistful of Dollars' Opens; Western Film Cliches All Used in Movie Cowboy Star From TV Featured as Killer". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Merrick, Amy (24 August 2014). "A Fistful of Dollars Ad". The TV Guide Historian. Blogspot. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Stevens, Brad (2003). Monte Hellman: His Life and Films. McFarland. p. 200.

- ^ Chasman (5 July 1998). "A Fistful of Dollars Prologue". Fistful of Leone. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Sutton, Mike (10 April 2005). "A Fistful Of Dollars (Special Edition)". The Digital Fix. Poisonous Monkey. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Rich, Jamie S. (29 August 2011). "A Fistful of Dollars (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Hughes, Howard (2006). Once Upon A Time in the Italian West: The Filmgoers' Guide to Spaghetti Westerns. I.B. Tauris & Co. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-85773-045-9.

- ^ "A Fistful of Dollars (Per un Pugno di Dollari) (1964)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ a b Chilton, Martin. "A Fistful of Dollars to be shown at Cannes Film Festival". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Galbraith IV, Stuart (2001). The Emperor and the Wolf. New York: Faber and Faber. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- ^ Gelten, Simon. "FISTFUL - The Whole Story, part 2 - The Spaghetti Western Database". Spaghetti Western Database. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "A Fistful of Dollars and Yojimbo". Side B Magazine. 14 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ The BFI Companion to the Western, 1988.

- ^ Frayling 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Fridlund, Bert (2005). "Classical American Western and Spaghetti Western: A Comparison of Shane and A Fistful of Dollars". 2003 Film & History CD-ROM Annual. Cleveland: Film & History.

- ^ "Services: Digital Film Restoration". Prasad Group. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (13 May 2014). "Cannes: Quentin Tarantino to Host Screening of 'A Fistful of Dollars'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

Text notes

- ^ The character, notably publicised as "the Man with No Name", is listed in the credits as "Joe" and is so called, in multiple instances, by the character Piripero; nevertheless, that may not be his real name.

References

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- Munn, Michael (1992). Clint Eastwood: Hollywood's Loner. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-790-X.

- Frayling, Christopher (2006). Spaghetti westerns : cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone (Revised paperback ed.). London: I. B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 978-1845112073.

- Giusti, Marco (2007). Dizionario del western all'italiana (1. ed. Oscar varia. ed.). Milano: Oscar Mondadori. ISBN 978-88-04-57277-0.

External links

- A Fistful of Dollars at IMDb

- A Fistful of Dollars at the TCM Movie Database

- Template:Amg movie

- A Fistful of Dollars at Box Office Mojo

- A Fistful of Dollars at the Spaghetti Western Database

- A Comparison of Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars and Last Man Standing

- 1964 films

- 1964 Western (genre) films

- Adaptations of works by Akira Kurosawa

- Dollars Trilogy

- Films scored by Ennio Morricone

- Films directed by Sergio Leone

- Films set in Mexico

- Films shot in Madrid

- Italian-language films

- Italian Western (genre) films

- Italian films

- Films involved in plagiarism controversies

- West German films

- Spaghetti Western films

- Films shot in Almería

- Constantin Film films