Double Dragon (hacking group)

| Formation | 2012 |

|---|---|

| Type | Advanced persistent threat |

| Purpose | Cyberespionage, cyberwarfare, Cybercrime |

Region | China |

| Methods | spearphishing, malware, supply chain attack |

Official language | Mandarin |

Formerly called | APT 41, Barium, Winnti, Wicked Spider, Wicked Panda, TG-2633, Bronze Atlas, Red Kelpie, Blackfly |

Double Dragon ( (also known as APT41, Barium, Winnti, Wicked Panda, Wicked Spider,[1] TG-2633, Bronze Atlas, Red Kelpie, Blackfly[2]) is a hacking organization with alleged ties to China. Classified as an advanced persistent threat, the organization was named by the US Department of Justice in September 2020 in relation to charges brought against five Chinese and two Malaysian nationals for allegedly compromising more than 100 companies around the world.[3][4][5][6]

In 2019, the cybersecurity company FireEye stated with high confidence that the group was sponsored by the Chinese Communist Party while conducting operations for financial gain.[7] The name “Double Dragon” originates from the duality of their operation, as they engage in espionage and individual financial gain.[8] The devices they use are usually used for state-sponsored intelligence.

Investigations conducted by FireEye have found APT 41 operations in multiple sectors, such as healthcare, telecommunications, and technology.[7] The group conducts many of its financial activities in the video game industry, including development studios, distributors, and publishers.[9] The organisation has conducted multiple operations in 14 countries, most notably the United States of America. Such activities include incidents of tracking, the compromising of business supply chains, and collecting surveillance data.[10] APT 41’s operations are described as "moonlighting" due to their balance of espionage supported by the Chinese state and financially motivated activities outside of state authorisation in their downtime.[7][11] As such, it is harder to ascertain whether particular incidents are state-directed or not.[12]

Ties with Chinese Government

APT 41 uses cyber-espionage malware typically kept exclusive to the government.[13] This characteristic is not uncommon for other advanced persistent threats, as this allows them to derive information to spy on high-profile targets or make contact with them to gain information that benefits national interest.[14] APT 41 relation to the Chinese state can be evidenced by the fact that none of this information is on the dark web and may be obtained by the Chinese Communist Party.[15]

APT 41 targeting is consistent with the Chinese government’s national plans to move into high research and development fields and increase production capabilities. Such initiatives coincide with the Chinese government’s “Made in China 2025” plan, aiming to move Chinese production into high-value fields such as pharmacy, semi-conductors, and other high-tech sectors.[7][16]

FireEye has also evaluated “with moderate confidence” that APT 41 may engage in contract work associated with the Chinese government. Identified personas associated with the group have previously advertised their skills as hackers for hire. Their usage of HOMEUNIX and PHOTO in their personal, financially motivated operations, which are malware unaccessible to the public used by other state-sponsored espionage actors evidences this stance.[7] It is also recognised in China that more skilled hackers tend to work in the private sector under government contracts due to the higher pay.[17] The FireEye report also notes that the Chinese state has depended on contractors to assist with state operations focused on cyber-espionage, as demonstrated by prior Chinese advanced persistent threats like APT 10.[7][18] APT 41 is viewed by some as potentially made up of skilled Chinese citizens, who are utilised and employed by the Chinese government, leading to the assumptions that members of the group often work two jobs, which is supported by their operating hours.[7][19]

Espionage Activity

APT 41’s targeting is deemed by FireEye to correlate with China’s national strategies associated with the “Made in China 2025” plan.[7][19][20]The targeting of tech firms align with Chinese interest in developing high-tech instruments domestically, as demonstrated by the 12th and 13th Five-Year Plans.[7] The attack on organisations in various different sectors is believed by FireEye to be indicative of APT 41 fulfilling specifically assigned tasks. Campaigns attributed to APT 41 also demonstrate that the group is used to obtain information before major political and financial events.[7][20]

In a FireEye security academic conference, it was confirmed that the German company, TeamViewer AG, behind the popular software of the same name which allowed system control remotely, was hacked in June 2016 by APT 41. The group was able to access the systems of TeamViewer users around the world, gaining access to management details and information regarding businesses.[21]

Financially Motivated Activities

APT 41 has targeted the video-game industry for the majority of its activity focused on financial gain.[7] Chinese internet forums also indicate that associated members linked to APT 41 advertise their hacking skills outside of Chinese office hours for their own profits.[19] In one case, FireEye reported, the group was able to generate virtual game currency and sell it to buyers through underground markets and laundering schemes,[1][7][10] which could have sold for up to $300,000 USD.[20] Attempts in deploying ransomware to profit from their operations, although it is not a typical method used by the group for collecting money.[7]

Techniques

The operating techniques of APT 41 are distinctive, particularly in their usage of passive backdoors compared to traditional backdoors. While traditional backdoors utilised by other advanced persistent threats are easily detectable, this technique is often much harder to detect.[7]

Techniques applied in financially motivated APT 41 activity include the application of software supply-chain compromises. This has allowed them to implement injected codes into legitimate files, which endanger other organisations by stealing data and altering systems.[22] Sophisticated malware is often deployed as well to remain undetected while extracting data.[19]

Bootkits are also malware used by the group, which is both difficult to detect and harder to find amongst other cyber espionage and cybercrime groups. This technique makes it harder to detect malicious code for security systems.[7]

Spearfishing emails are regularly utilised by APT 41 across both cyber espionage and financial attacks.[9] The group has sent many misleading and deceitful emails which attempt to take information from high-level targets after gathering personal data to increase the likelihood of success.[23] Targets have varied from media groups for espionage activities and bitcoin exchanges for financial gain.[7]

List of Malware Used

- ACEHASH

- ADORE.XSEC

- ASPXSPY

- BEACON

- CHINACHOP

- COLDJAVA

- CRACKSHOT

- CROSSWALK

- CROSSWALK.BIN

- DEADEYE

- DOWNTIME

- EASYNIGHT

- ENCRYPTORRAAS

- FRONTWHEEL

- GEARSHIFT

- GH0ST

- GOODLUCK

- HIGHNOON

- HIGHNOON.BIN

- HIGHNOON.LITE

- HIGHNOON.PASTEBOY

- HKDOOR

- HOMEUNIX

- HOTCHAI

- JUMPALL

- LATELUNCH

- LIFEBOAT

- LOWKEY

- njRAT

- PACMAN

- PHOTO

- POISONPLUG

- POISONPLUG.SHADOW

- POTROAST

- ROCKBOOT

- SAGEHIRE

- SWEETCANDLE

- SOGU

- TERA

- TIDYELF

- WIDETONE

- WINTERLOVE

- XDOOR

- XMRIG

- ZXSHELL[7]

Associated Personnel

In their earlier activities, APT 41 has used domains registered to the monikers “Zhang Xuguang” (simplified Chinese: 张旭光) and “Wolfzhi”. These online personas are associated with APT 41’s operations and specific online Chinese language forums, although the number of other individuals working for the group is unknown.[7] “Zhang Xuguang” has activity on the online forum Chinese Hackers Alliance (simplified Chinese: 华夏黑 客同盟). Information related to this individual includes his year of birth, 1989, and his former living in Inner Mongolia.[24] The persona has also posted on a forum regarding the Age of Wushu online game, using the moniker “injuriesa” in 2011.[7] Emails and online domains associated with “Wolfzhi” also lead to a data science community profile. Forum posts also suggest that the individual is from Beijing or the nearby province, Hebei.[7][24]

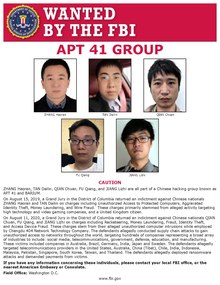

The FBI has also issued wanted posters for Haoran Zhang, Dailin Tan, Chuan Qian, Qiang Fu, and Lizhi Jiang, whom they have found to be linked with APT 41.[1] Zhang and Tan were indicted on August 15th, 2019, by the Grand Jury in the District of Columbia for charges associated with hacking offences, such as Unauthorised Access to Protected computers, Aggravated Identity Theft, Money Laundering and Wire Fraud.[25] These actions were conducted on high-tech companies, video-game companies and six unnamed individuals from the United States and the United Kingdom while the two worked together. The FBI also charged Qian, Fu, and Jiang on August 11th, 2020, for Racketeering, Money laundering, Fraud, and Identity Theft.[25] All three individuals were part of the management team of the Chengdu 404 Network Technology company, where the three and coworkers planned cyber attacks against companies and individuals in industries like communications, media, security, and government.[26] Such operations were to occur in countries like the United States, Brazil, Germany, India, Japan, Sweden, Tibet, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand.[1]

In August of 2020, Wong Ong Hua and Ling Yang Ching, were both charged with racketeering, conspiracy, identity theft, aggravated identity theft and fraud amongst others.[1] The United States Department of Justice says that the two Malaysian businessmen were working with the Chinese hackers to target video game companies in the United States, France, South Korea, Japan and Singapore and profit from these operations.[27] These schemes, particularly a series of computer intrusions involving gaming industries, were conducted under the Malaysian Company Sea Gamer Mall, founded by Wong.[1] On September 14th 2020, Malaysian authorities arrested both individuals in Sitawan.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Seven International Cyber Defendants, Including "Apt41" Actors, Charged In Connection With Computer Intrusion Campaigns Against More Than 100 Victims Globally" (Press release). Washington. United States Department of Justice. September 16, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ "APT 41 - Threat Group Cards: A Threat Actor Encyclopedia". apt.thaicert.or.th. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ Cimpanu, Catalin. "US charges five hackers from Chinese state-sponsored group APT41". ZDNet. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ "FBI Deputy Director David Bowdich's Remarks at Press Conference on China-Related Cyber Indictments". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Rodzi, Nadirah H. (2020-09-17). "Malaysian digital game firm's top execs facing extradition after US accuses them of cyber crimes". The Straits Times. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Yong, Charissa (2020-09-16). "China acting as a safe haven for its cyber criminals, says US". The Straits Times. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t APT41: A Dual Espionage and Cyber Crime Operation (Report). FireEye. 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ "[Video] State of the Hack: APT41 - Double Dragon: The Spy Who Fragged Me". FireEye. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ a b Kendzierskyj, Stefan; Jahankhani, Hamid (2020), "Critical National Infrastructure, C4ISR and Cyber Weapons in the Digital Age", Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3–21, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-35746-7_1, ISBN 978-3-030-35745-0, retrieved 2021-05-25

- ^ a b Kianpour, Mazaher (2021). "Socio-Technical Root Cause Analysis of Cyber-enabled Theft of the U.S. Intellectual Property -- The Case of APT41". arXiv:2103.04901 [cs.CR].

- ^ Steffens, Timo (2020), "Advanced Persistent Threats", Attribution of Advanced Persistent Threats, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 3–21, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-61313-9_1, ISBN 978-3-662-61312-2, retrieved 2021-05-25

- ^ Bateman., Jon. War, Terrorism, and Catastrophe in Cyber Insurance: Understanding and Reforming Exclusions. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. OCLC 1229752520.

- ^ Naughton, Liam; Daly, Herbert (2020), "Augmented Humanity: Data, Privacy and Security", Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 73–93, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-35746-7_5, ISBN 978-3-030-35745-0, retrieved 2021-05-25

- ^ Lightfoot, Katie (2020). Examining Chinese Cyber-Attacks: Targets and Threat Mitigations (Msc). Utica College.

- ^ Chen, Ming Shen (2019). "China's Data Collection on US Citizens:Implications, Risks, and Solutions" (PDF). Journal of Science Policy & Governance. 15.

- ^ "Potential for China Cyber Response to Heightened U.S.–China Tensions" (Press release). Rosslyn. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. October 1, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Wong, Edward (2013-05-22). "Hackers Find China Is Land of Opportunity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Lyall, Nicholas (2018-03-01). "China's Cyber Militias". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Cyber Intelligence Lab - Macquarie University (2020). Australian Universities under Attack: A CiLab PACE Project (PDF) (Report). Macquarie University.

{{cite report}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|authors=(help) - ^ a b c Doffman, Zak. "Spies By Day, Thieves By Night—China's Hackers Using Espionage Tools For Personal Gain: Report". Forbes. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ Hu, Chunhui; Zhang, Ling; Luo, Xian; Chen, Jianfeng (2020-04-15). "Research of Global Strategic Cyberspace Security Risk Evaluation System Based on Knowledge Service". Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Geoinformatics and Data Analysis. New York, NY, USA: ACM: 140–146. doi:10.1145/3397056.3397084. ISBN 978-1-4503-7741-6.

- ^ Kim, Bong-Jae; Lee, Seok-Won (2020). "Understanding and recommending security requirements from problem domain ontology: A cognitive three-layered approach". Journal of Systems and Software. 169: 110695. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.110695. ISSN 0164-1212.

- ^ O'Leary, Daniel E. (2019). "What Phishing E-mails Reveal: An Exploratory Analysis of Phishing Attempts Using Text Analyzes". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3427436. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ a b Aug 2019, Max Eddy 7; P.m, 11 (2019-08-07). "APT41 Is Not Your Usual Chinese Hacker Group". PCMag Australia. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Chinese and Malaysian hackers charged by US over attacks". BBC News. 2020-09-16. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ Geller, Eric. "U.S. charges 5 Chinese hackers, 2 accomplices with broad campaign of cyberattacks". POLITICO. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ "DOJ says five Chinese nationals hacked into 100 U.S. companies". NBC News. Retrieved 2021-05-29.