User:Qiushufang/sandbox

Han

Tang

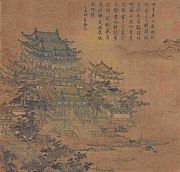

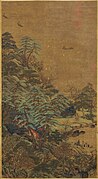

Li Zhaodao (675-758)

-

Luoyang Pavilion

-

Dragon boat race by Li Zhaodao (675-758)

Various

-

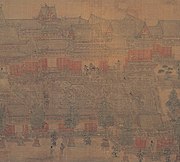

Li Sixun painting (651-716)

-

The Emperor's arrival at the summer palace Jiucheng by Li Sixun

-

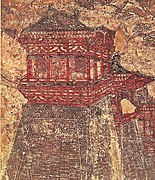

A guard tower in Prince Yide's tomb mural

-

The Yueyang Tower by Li Sheng (fl. 908-925), Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

-

Moung Kuanglu by Jing Hao (855-915)

-

A 10th-century mural painting in the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang showing monastic architecture from Mount Wutai, Tang dynasty

Song

Guo Zhongshu (929-977)

-

Summer Palace of Emperor Ming

-

Bringing a Lute to an Immortal's Pavilion

-

Riverside grain mill

-

Wangchuan villa

-

Wangchuan villa

Li Song (1190-1264)

Various

-

Streams and Mountains Under Fresh Snow by Gao Keming (1008-1053)

-

The Process of Making Silk by Liang Kai (12-13th c.)

-

Xiao Getting the Orchid Pavilion Scroll by Deception by Juran (960-)

-

A Solitary Temple Amid Clearing Peaks by Li Cheng(919–967)

-

Illustration to the Second Prose Poem on the Red Cliff by Qiao Zhongchang (960-1127)

-

Illustrations to six texts from the Xiaoya section of the Book of Songs by Ma Hezhi (12th c.)

-

Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety by Ma Hezhi (fl. 1131-1189)

-

Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety by Ma Hezhi (fl. 1131-1189)

-

Riverbank by Dong Yuan (c. 934 – c. 962)

-

A Palace by Zhao Boju (1120-1182)

-

Pure Summer at Liquan

-

Four Events from the Jingde Reign (1004-1007)

-

Burning Incense as an Offering by "Master" Li

-

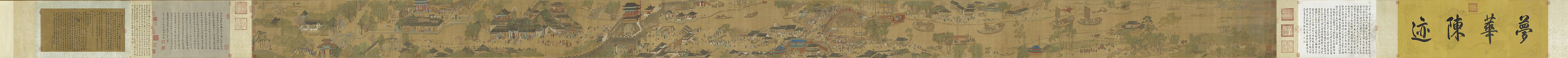

Games in the Jinming Pool by Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145)

Yuan

Xia Yong (14th c.)

-

Fengle lou

-

Yingshui Loutai

-

Lü Dongbin passing Yueyang Tower

-

The Yellow Tower

Wang Zhenpeng (14th c.)

-

Dragon Baot Regatta by Wang Zhenpeng, 1310

-

Daming Palace, attributed to Wang Zhenpeng but likely 15th century production

Various

-

Spring Dawn Over Elixir Terrace by Lu Guang, Yuan dynasty

-

View of Immortal Mountain Tower by Lu Guang, Yuan dynasty

-

Han yuan tu by Li Rongjin, Yuan dynasty

-

Jianzhang Palace, Yuan dynasty

-

Mountain Villa by Sheng Mao (1310-1360)

-

Clearing After Sudden Snow by Huang Gongwang (1269–1354)

-

:Landscape with Pavilion, attributed to Sun Junze

-

'Landscape with Buildings' by Sun Junze, early 14th c.

-

Pavilion of Prince Teng by anonymous

-

Pavilion of Prince Teng by anonymous

-

Zhu Haogu's studio (14th century)

Ming

-

The Simple Retreat by Wang Meng (1308-1385)

-

Ming copy of Li Sixun's painting (651-716)

-

Ming copy of Emperor Ming (Emperor Xuanzong of Tang) goes to Shu by Li Sunxu (651-716)

-

The Yueyang tower during the Ming dynasty

-

Shanglin Park by Qiu Ying (1494-1552)

-

Han Palace Spring Daybreak by Qiu Ying

-

Viewing the Pass List by Qiu Ying

-

Fang zhao bo su hou chi bi by Wen Zhengming (1470-1559)

-

Morning Boat Jam by Yuan Shangtong (16th-17th c.)

-

Ming Emperor Xianzong Enjoying the Lantern Festival by Shang Xi, 1485

-

Mountain Hamlet Lofty Retreat by Li Zai (14-15th c.)

-

River Village in a Rainstorm by Lü-Wenying (c. 1500)

Along the River During the Qingming Festival

Religion in the Tang dynasty

Religion in the Tang dynasty (618-907) was primarily composed of three institutional religions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, in addition to Chinese folk religion.

Religion in the Song dynasty

Religion in the Song dynasty (960–1279) was primarily composed of three institutional religions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, in addition to Chinese folk religion.

Folk religion

During the Song dynasty, the three major religions and to an extent Neo-Confucianism, underwent a process of rationalizing Chinese folk religion by systematically incorporating and categorizing deities into a universal pantheon. This was encouraged by state policy, which also pruned religious conduct by sanctioning correct and incorrect religious practices. For example, the Neo-Confucian scholar-official Huang Zhen (1213-81) forbade rowing boats to welcome gods, destroyed 1300 such boats, and destroyed "perverse temples" and forbade the worship of epidemic gods.[1]

Buddhism

Tiantai Buddhism is synonymous with the development of lay Buddhism and Pure Land Buddhism.[1]

Taoism

Zhengyi Taoism shifted imperial interest from elite Maoshan to Zhengyi.[1] It was mainly exorcistic.[2]

Neo-Confucianism

Neo-Confucianism, also known as dao xue (Learning of the Way), li xue (Learning of the Principle), and xin xue (Learning of the Heart/Mind) was a major philosophical school that emerged during the Song dynasty as a response to the dominance of Taoism and Buddhism in intellectual and political arenas.[3] As a result, Neo-Confucianism was conceived among elite scholar-officials that sought to update Confucianism by rejecting superstitious and metaphysical elements influenced by Buddhism and Taoism.[4]

The Song pioneers of Neo-Confucianism include Shao Yong (1017-1077), Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073), Zhang Zai (1020-1077), Cheng Hao (1032-1085), Cheng Yi (1033-1107), Zhu Xi (1130-1200), and Lu Jiuyuan (1139-1192). They heavily emphasized the imperial examinations and the Confucian values exemplified in the writings of Tang scholars Liu Yuxi (772-842), Liu Zongyuan (773–819), and Han Yu (768-824).[3] Their efforts to produce systems of Confucian doctrine produced three new schools: Daoxue, Lixue, and Xinxue, collectively translated as Neo-Confucianism. Lixue emphasized studying the Classics in order to understand Principle, the source of moral norms. Xinxue argued that the heart/mind was the source of all moral values and understanding it was the only path to enlightenment.[3]

After Neo-Confucianism became the state orthodoxy in 1241, Neo-Confucian academies began to enjoy the same sponsorship as Buddhist and Taoist temples. These academies were often associated with shrines and sacrifices to Confucian scholars, in contrast to the deity worshiping Buddhist and Taoist temples.[5]

Shao Yong (1017-1077)

Shao Yong was born in 1017 to a family of humble scholars in Fanyang (southwest of modern Beijing). Invasions by the Liao dynasty led the Shaos to eventually settle in Weizhou (modern Hui County, Henan). Shao Yong never participated in the imperial examinations nor did he pursue an official career, despite receiving at least two imperial summons (in 1061 and 1069). In 1049, Shao moved to Luoyang and taught Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi in the mid-1050s. In 1069, Wang Anshi began to implement his New Policies, which resulted in a number of detractors resigning and relocating to Luoyang, which became a refuge for the anti-Wang bureaucrats. Shao emerged as a sagely council this group. Despite, or because of his influence, Shao remained unemployed for the majority of his life, living off of his closest associates Sima Guang, Cheng Hao, and Lü Gongzhu, who provided him with basic necessities including his home, which he called his "nest of peace and happiness."[6]

Unlike later Neo-Confucianists, Shao Yong openly admired Taoist iconoclasts, did not emphasize the Confucian virtues of ren and yi, or hold li as the most important concept. Instead, Shao believed that shu (number) was the first useful tool created by the Taiji (Supreme Ultimate) that could be used to advance knowledge. He considered a the "teaching or learning of Before Heaven," a predictive knowledge based on the application of number, to be the most esteemed category of knowledge. Number was the most perfect mode to describe this type of knowledge because of its inherent regulative features. To understand and fully utilize the xin (heart/mind), Shao believed that number had to be used.[7]

Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073)

There is no indication that Zhou Dunyi ever participated in or passed the imperial examinations. However in 1036, he secured an official post as a keeper of records, likely owing to his substantial connections: both his father and maternal uncle were jinshi degree holders. Zhou did not assume his first post until 1040 due to his mother's death in 1037. Once he commenced his work, Zhou distinguished himself as an adjudicator of legal disputes and an erudite Confucianist. In the 1040s, Zhou attracted a number of pupils, including Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi from 1046-7. They evidently did no like him and referred to him as a "decrepit Chan stranger."[8] In 1060, he met and spent several days with Wang Anshi, who had a highly favorable impression of Zhou. In 1068, Zhou became assistant fiscal commissioner, and in 1071, a judicial commissioner. In 1072, he retired to Lushan in modern Dao County, Hunan, and died the following year.[8]

Zhou Dunyi is considered the founder of Daoxue (Learning of the Way), but he did not consciously seek to become the head of a movement, and only received the position upon posthumous elevation by Zhu Xi. According to Zhu, Zhou Dunyi was the linkage between the classical patriarchs of Confucianism that ended with Mengzi with their time. Zhou himself believed that the Taiji (Supreme Ultimate) was the progenitor of everything, and within the Taiji, the dao or Way and the li (Principle) are united by sincerity. Zhou heavily emphasized cultivating sincerity and that sincerity was the foundation of the sage ('sagehood is nothing more than sincerity').[9]

Zhang Zai (1020-1077)

Zhang Zai (1020-1077) was born in 1020 in Daliang, near Kaifeng. After the death of his father, his family moved to Hengqu (in modern Mei County, Shaanxi). During his youth, Zhang was infatuated with the study of military matters and even organized a militia force with the intent of capturing territory from the Western Xia. In 1040, Zhang was convinced by Fan Zhongyan to give up a career in the military, which led Zhang to forays in Buddhism and Taoism. In 1056, Zhang gave lectures on the Yijing in Kaifeng, the Song capital, and thus came to attention of several prominent scholars, including Sima Guang. After meeting his nephews, Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi, Zhang gave up on public lecturing because he felt their knowledge surpassed his own. After that, Zhang dedicated himself to Confucian learning.[10]

Zhang Zai and his nephew Cheng Hao obtained jinshi degrees in 1057. For the next decade, Zhang served in a number of provisional positions, including administrator in charge of laws. In 1069, Zhang was summoned for an audience with Emperor Shenzong of Song, who was pleased with his answers on how best to govern the empire. Shenzong requested Zhang to deliberate on Wang Anshi's New Policies, but Zhang was not keen on participating. Later when Wang tried to recruit him as a participant in implementing the New Policies, Zhang advised Wang to conduct himself properly and cease pursuing a policy of micro-management. Displeased with Zhang's attitude, Wang demoted him to the provinces and almost drove him to quitting office altogether. After the death of his brother, Zhang Jian (1030-1076), Zhang Zai resigned and spent the remaining year of his life devoted to study and teaching.[11]

Zhang Zai believed in a materialist conception of the world and theorized that the basic element of the universe was qi. Zhang believed that everything was made of qi and thus nothing could be truly empty. He used his belief in the universal presence of qi to caution against withdrawal from the world in the manner of Buddhis clerics. Zhang also emphasized a link between the heart/mind with the body, and that sincerity upheld the natural order. His primary contribution to the Neo-Confucianist movement was his argument against the Buddhist conception of nothingness, which he considered nothing more than a more dispersed state of qi.[11]

Cheng Hao (1032-1085)

Cheng Hao was born in Huangpo in present day Hubei to a highly educated family. Cheng Hao learned to read poetry by the age of eight and composed poems by the age of ten. At the age of 12 and 13, he was considered mature and likable while boarding at the county school. At the age of 15, he and his brother Yi studied under Zhou Dunyi, from whom their main takeaway was to disregard the examination standards and to see the Way. Cheng Hao spent around ten years learning from various schools. In 1057, Cheng Hao obtained the jinshi degree. From 1060-1062, he served as assistant magistrate in Huxian (in modern Shaanxi). In 1063, he was reappointed as assistant magistrate in Shangyuan (in modern Jiangsu) and magistrate in 1065. During his tenure, Cheng Hao balanced land distribution, reduced taxes, and arranged for ill soldiers to receive food and medicine. In his next appointment as magistrate of Jincheng in Zezhou (in modern Shaanxi), Cheng Hao promoted education, making his motto "every village should have a school."[12] In 1069, Cheng Hao was reappointed to the central government, where he came to disagree with Wang Anshi's New Policies. Cheng Hao submitted several memorials, one of which said that certain patterns of humane government did not change with time. Two years later, he was reassigned to probationary administrative assistant in Zhenning Commandery and Caocun in Chanzhou (modern Puyang County, Henan). There was flooding at the time along the Yellow River and Cheng Hao successfully led efforts to contain the floods and repair the dikes. His father died the next year, causing him to resign and return to Luoyang. In 1075 he was assigned to magistrate in Fugou (in modern Henan) where there was a drought. He stabilized commodity prices, dug wells for irrigation, and established schools. According to his disciple, he kept the motto "treat the people as if treating the wounded" next to his desk.[13]. In 1080, Cheng Hao was removed from office. He died in the summer of 1085.[13]

Cheng Hao linked human nature (xing) to qi. Hao believed that evil was a part of human nature. he emphasized the importance of ren (humaneness), and ren could only be achieved by regarding Heaven and Earth as part of one's body. It was paramount to communicate between the extremities of the body, such that the imperial court should be conscientious, aware, and sympathetic to the people's suffering.[13]

Zhu Xi (1130-1200)

One of the pioneers of Neo-Confucianism, Zhu Xi (1130-1200), believed in "local initiatives and a sense of compassion, encouraging mutual aid within local communities."[14] Zhu Xi believed that the act of reading

Citations

- ^ a b c Lagerwey 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Lagerwey 2019, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Yao 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Lagerwey 2019, p. 121.

- ^ Lagerwey 2019, p. 129.

- ^ Yao 2003, p. 540.

- ^ Yao 2003, p. 541.

- ^ a b Yao 2003, p. 833.

- ^ Yao 2003, p. 834.

- ^ Yao 2003, p. 803-804.

- ^ a b Yao 2003, p. 804.

- ^ Yao 2003, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Yao 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Lagerwey 2019, p. 128.

Bibliography

- Ebrey, Patricia (1993), Religion and Society in T'ang and Sung China