Battle of Vukovar

| Battle of Vukovar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||

The Vukovar water tower, 2010. Heavily damaged in the battle, the tower has been preserved as a symbol of the conflict. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 36,000 | 1,800 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,103 killed, 2,500 wounded 110 tanks and armoured vehicles and 3 aircraft destroyed | 879 dead, 770 wounded | ||||||

| 1,131 civilians killed | |||||||

The Battle of Vukovar was an 87-day siege of Vukovar in eastern Croatia by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), supported by various paramilitary forces from Serbia, between August and November 1991. Before the Croatian War of Independence the Baroque town was a prosperous, mixed community of Croats, Serbs and other ethnic groups. As Yugoslavia began to break up, Serbia's President Slobodan Milošević and Croatia's President Franjo Tuđman began pursuing nationalist politics. In 1990, an armed insurrection was started by Croatian Serb militias, supported by the Serbian government and paramilitary groups, who seized control of Serb-populated areas of Croatia. The JNA began to intervene in favour of the rebellion, and conflict broke out in the eastern Croatian region of Slavonia in May 1991. In August, the JNA launched a full-scale attack against Croatian-held territory in eastern Slavonia, including Vukovar.

Vukovar was defended by around 1,800 lightly armed soldiers of the Croatian National Guard (ZNG) and civilian volunteers, against as many as 36,000 JNA soldiers and Serb paramilitaries equipped with heavy armour and artillery. During the battle, shells and rockets were fired into the town at a rate of up to 12,000 a day.[3] At the time, it was the fiercest and most protracted battle seen in Europe since 1945, and Vukovar was the first major European town to be entirely destroyed since the Second World War.[4][5] When Vukovar fell on 18 November 1991, several hundred soldiers and civilians were massacred by Serb forces and at least 20,000 inhabitants were expelled.[6] Overall, around 3,000 people died during the battle. Most of Vukovar was ethnically cleansed of its non-Serb population and became part of the self-declared proto-state Republic of Serbian Krajina. Several Serb military and political officials, including Milošević, were later indicted and in some cases jailed for war crimes committed during and after the battle.

The battle exhausted the JNA and proved a turning point in the Croatian war. A ceasefire was declared a few weeks later. Vukovar remained in Serb hands until 1998, when it was peacefully reintegrated into Croatia with the signing of the Erdut Agreement. It has since been rebuilt but has less than half of its pre-war population and many buildings are still scarred by the battle. Its two principal ethnic communities remain deeply divided and it has not regained its former prosperity.

Background

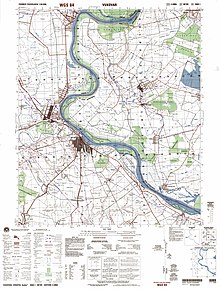

Vukovar is an important regional centre on Croatia's eastern border, situated in eastern Slavonia on the west bank of the Danube river. The area has a diverse population of Croats, Serbs, Hungarians, Slovaks, Ruthenians and many other nationalities, who had lived together for centuries in relative harmony before the Croatian War of Independence. It was also one of the wealthiest areas of Yugoslavia before the conflict.[7] Vukovar's long-standing prosperity was reflected in one of Croatia's finest ensembles of Baroque architecture.[8]

The region underwent major demographic changes following the Second World War, when its ethnic German inhabitants were expelled and replaced with settlers from elsewhere in Yugoslavia.[9] In 1991, the last Yugoslav census recorded the Vukovar municipality, which included the town and surrounding villages, as having 84,189 inhabitants, of whom 43.8 percent were Croats, 37.5 percent were Serbs and the remainder were members of other ethnic groups. The town's population was 47 percent Croat and 32.3 percent Serb.[10]

From 1945, Yugoslavia was governed as a federal socialist state comprising six newly created republics – Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia.[11] The current border between Serbia and Croatia was defined in 1945 by a Yugoslav federal government commission which assigned areas with a Serb majority to the Socialist Republic of Serbia and those with a Croat majority to the Socialist Republic of Croatia. Nevertheless, a sizable Serb minority remained within the latter.[12]

Following the death of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980, long-suppressed ethnic nationalism revived and the individual republics began to assert their authority more strongly as the federal government weakened. Slovenia and Croatia moved towards multi-party democracy and economic reform, but Serbia's authoritarian communist President Slobodan Milošević opposed reform and sought to increase the power of the Yugoslav government.[13] In 1990, Slovenia and Croatia held elections that ended communist rule and brought pro-independence nationalist parties to power in both republics. In Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) of Franjo Tuđman took power, with Tuđman as president.[14]

Tuđman's programme was opposed by many members of Croatia's Serb minority, towards whom he was overtly antagonistic.[14] Croatia's Serb Democratic Party (SDS), supported by Milošević, denounced the HDZ as a reincarnation of the nationalist-fascist Ustaše movement, which had massacred hundreds of thousands of Serbs during the Second World War.[15] From mid-1990, the SDS mounted an armed rebellion in Serb-inhabited areas of Croatia and set up the self-declared Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina, with covert support from the Serbian government and Serbian paramilitary groups. The Croatian government rapidly lost control of large swathes of the republic.[15] In February 1991, the Krajina Serbs declared independence from Croatia and announced that they would unite with Serbia. Other Serb communities in Croatia also announced that they would secede and established their own militias.[16]

Prelude to the battle

The conflict between Serbs and Croats spread to eastern Slavonia in early 1991. On 1 April, Serb villagers around Vukovar and other towns in eastern Slavonia began to erect barricades across main roads.[17] The White Eagles, a Serbian paramilitary group led by Vojislav Šešelj, moved into the Serb-populated village of Borovo Selo just north of Vukovar.[18] In mid-April 1991, an incident occurred in the outskirts of Borovo Selo when three Armbrust shoulder-launched anti-tank missiles were fired on Serb positions. There were allegations that Gojko Šušak, at the time the Deputy Minister of Defence, led the attack.[19] There were no casualties, but the attack aggravated and deepened ethnic tensions.[20] On 2 May, Serb paramilitaries ambushed two Croatian police buses in the centre of Borovo Selo, killing 12 policemen and injuring 22 more.[17] One Serb paramilitary was also killed.[21] The Battle of Borovo Selo represented the worst act of violence between the country's Serbs and Croats since the Second World War.[22] It enraged many Croatians and led to a surge of ethnic violence across Slavonia.[23]

Shortly after, Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) units moved into Borovo Selo. The army's intervention was welcomed by local Croatian leaders, but Croatia's Deputy Interior Minister, Milan Brezak, accused the JNA of preventing the Croatian police from dealing with the paramilitaries.[24][25] Gun battles broke out across the region between rival militias.[23] In Vukovar, Croatians harassed Serb residents, sometimes violently. Croatian police forcibly took over the local radio station, Radio Vukovar, and Serb members of the station's ethnically mixed staff were fired and replaced with Croats.[26] Serb militias systematically blocked transport routes in the predominantly Serb-inhabited countryside around Vukovar, and within days the town could only be reached by an unpaved track running through Croat-inhabited villages. The atmosphere in Vukovar was said to be "murderous".[27]

On 19 May 1991, the Croatian government held a nationwide referendum on a declaration of sovereignty. In Vukovar, as elsewhere in Croatia, hardline Serb nationalists urged Serbs to boycott the referendum, while moderates advocated using the poll to register opposition to independence. Many local Serbs did vote.[28] The referendum passed with 94 percent nationally voting in favour.[29]

Violence in and around Vukovar worsened after the independence referendum. Repeated gun and bomb attacks were reported in the town and surrounding villages.[30] Sporadic shelling of the city started in June, and increased in intensity throughout the summer. Borovo Naselje, the Croatian-held northern suburb of Vukovar, sustained a significant shelling on 4 July.[31] Serb paramilitaries expelled thousands of non-Serbs from their homes in the municipality.[32] Croatian paramilitaries, led by Tomislav Merčep, attacked Serbs in and around Vukovar. Between 30 and 86 Serbs disappeared or were killed, and thousands of others fled their homes.[33][34] A Croatian government representative in Vukovar told the Zagreb authorities that "the city is again [the] victim of terror, armed strife and provocative shoot-outs with potentially unfathomable consequences. The policy pursued so far has created an atmosphere of terror among the Croatian and Serbian population."[35] Gunmen from both sides burned and looted hundreds of houses and farms in the area.[36]

The conflict blurred ethnic lines. Many Serbs who had lived in Vukovar for generations – known as the starosedioci or "old settlers" – resisted the propaganda coming from Belgrade and Knin and continued to live peacefully with their Croatian neighbours. The došljaci, or "newcomers", whose families had relocated from southern Serbia and Montenegro to replace the deported Germans after 1945, were the most responsive to nationalist appeals. The journalist Paolo Rumiz describes how they "tried to win their coethnics over to the patriotic mobilization, and when they had no success with that, they killed them, plundered their property and goods, or drove them away. The old settlers would not let themselves be stirred up against other nationalities."[37] When Croats fled the fighting they often gave their house keys for safekeeping to their Serb neighbours, whom they trusted, rather than to the Croatian police. The political scientist Sabrina P. Ramet notes that a distinctive feature of the war in eastern Slavonia was "the mobilization of those who were not integrated into the multi-cultural life of the cities against urban multi-culturalism."[38] Former Belgrade mayor Bogdan Bogdanović characterised the attack on Vukovar as an act of urbicide, a deliberate assault on urbanism.[39]

Opposing forces

By the end of July 1991, an improvised Croatian defence force in Vukovar was almost surrounded by Serbian militias in the neighbouring villages. Paramilitaries, JNA soldiers and Serbian Territorial Defence (TO) conscripts were present in Serb-inhabited areas. There was a small JNA barracks in Vukovar's Sajmište district, surrounded by Croatian-controlled territory.[40] Although the two sides were commonly referred to as "Croatian" and "Serbian" or "Yugoslav", Serbs and Croats as well as many other of Yugoslavia's national groups fought on both sides. The first commander of the attacking force was Macedonian.[41] Serbs and members of other ethnicities made up a substantial portion of the Croatian defenders.[42]

Croatian forces

The Croatian force in Vukovar comprised 1,800 men assembled from units of the newly created Croatian National Guard, including 400 members of the 3rd Guards Brigade and the 1st Guards Brigade. The 4th Battalion of the 3rd Guards Brigade was stationed in the city from the beginning, while elements of the 1st Guards Brigade arrived retreating from elsewhere in western Syrmia. In addition to the guardsmen there were 300 police officers and 1,100 civilian volunteers from Vukovar and nearby communities.[43] The bulk of the force had initially been organised in an improvised manner.[44] In late September 1991, it was formally reorganised as the 204th Vukovar Brigade, also known as the 124th Brigade.[44]

Volunteers arrived from other parts of Croatia, including 58 members of the far-right paramilitary Croatian Defence Forces (HOS),[45] backed by Dobroslav Paraga's extreme nationalist Croatian Party of Rights (HSP).[46] The defenders were a cross-section of Vukovar society. As many as one-third were non-Croats, including Serbs, Ruthenians, Hungarians and members of other ethnicities.[42] About 100 of the defenders were Serbs. "We had complete confidence in them," one Croatian veteran later remarked. "They defended Vukovar alongside us."[47]

Croatian forces in Vukovar were commanded by Mile Dedaković, a former JNA officer who had joined the ZNG and volunteered to take charge of the town's defences.[48] During the battle, he went by the nom de guerre Jastreb ("Hawk").[49] Gojko Šušak, by now Croatia's Minister of Defence, used Dedaković as an example of how Serbs were also taking part in Vukovar's defence.[50] The claim was later reprinted by independent sources,[49] but was false.[50] Dedaković's second-in-command, Branko Borković, was another former JNA officer who had volunteered for service in Vukovar.[51] The two men established a unified command structure, organised the defenders into a single brigade and implemented an integrated defence system.[52] A defensive ring of six sectors was established, each assigned to one unit within the 204th Brigade.[53] The defenders used a network of cellars, canals, ditches and trenches to redeploy around the sectors as needed.[54]

At the start of the battle, they were poorly armed and many were equipped only with hunting rifles. They relied mostly on light infantry weapons, but obtained a few artillery pieces and anti-aircraft guns and improvised their own land mines.[55] They also obtained several hundred anti-tank weapons such as M79 and M80 rocket launchers, but were critically short of ammunition throughout the battle.[43][56] The capture of JNA barracks somewhat improved the situation as Vukovar had the priority in the supply of arms. It is estimated that the Vukovar battlefield consumed around 55–60 percent of all ammunition available to the Croatian forces.[57]

Yugoslav and Serb forces

The attacking force included JNA soldiers conscripted from across Yugoslavia, members of the TO, Chetniks (Serbian nationalist paramilitaries), local Serb militiamen and units of the Yugoslav Navy and the Yugoslav Air Force.[55] At their peak, the Yugoslav and Serb forces in the vicinity of Vukovar numbered about 36,000.[58] They were equipped with heavy artillery, rockets and tanks and supported by aircraft and naval vessels on the Danube.[55]

Although the battle was fought primarily by the federal Yugoslav military, the government of Serbia was directly involved. The Serbian secret police agency, the SDB, took part in military operations, and some of its officers commanded Serbian TO units fighting in Vukovar.[59] Serbia's Ministry of Internal Affairs directed the activities of the paramilitaries.[60] It was also responsible for arming and equipping them.[61] Slobodan Milošević was later accused of direct involvement. According to Veselin Šljivančanin, who was later convicted of war crimes committed at Vukovar, the order to shell Vukovar came "from Dedinje" – the elite Belgrade quarter where Milošević lived.[62]

At the start of the war in Slovenia, the army still saw itself as the defender of a federal, communist Yugoslavia, rather than an instrument of Serbian nationalism. Its head, General Veljko Kadijević, the Yugoslav Minister of Defence and a committed communist, initially sought to forcibly keep Yugoslavia together and proclaimed the army's neutrality in the Serb-Croat conflict.[63] The JNA leadership aimed to cut Croatia in two by seizing the Serb-inhabited inland regions, almost all of the Dalmatian coast and much of central and eastern Croatia. It aimed to force Croatia's political leadership to capitulate and renegotiate its membership of Yugoslavia.[64] The JNA's leadership was not yet dominated by ethnic Serbs, and these early goals reflected the Yugoslav outlook of its multiethnic leadership. Kadijević was half-Croat and half-Serb, his deputy was a Slovene, the commander of the JNA forces in the first phase of the battle was a Macedonian, and the head of the Yugoslav Air Force, which repeatedly bombed Vukovar during the battle, was a Croat.[41][65]

The loss of Slovenia in the Ten-Day War made it impossible to fulfil the original objective of keeping Yugoslavia intact. Many of the Serb members of the army no longer wanted to fight for a multiethnic Yugoslavia. The army developed an increasingly Serbian character as non-Serbs deserted or refused to be drafted.[63] Some JNA commanders overtly supported the Serb rebels in Croatia and provided them with weapons.[61] Although Kadijević and other senior JNA commanders initially argued that "the JNA must defend all the nations of Yugoslavia",[61] they eventually recognised that they had no chance of achieving their original goals, and threw their support behind the rebel Serbs of Croatia.[63]

Yugoslav and Serb propaganda portrayed Croatian separatists as genocidal Ustaše, who had illegally taken over Yugoslav territory and were threatening Serb civilians in a reprise of the anti-Serb pogroms of the Second World War.[40] Kadijević later justified the JNA's offensive against Vukovar on the grounds that it was part of the "backbone of the Croatian army" and had to be "liberated". The JNA's periodical Narodna Armija claimed after the battle that Vukovar "had for decades been prepared to support German military penetration down the Danube."[46] Šešelj declared: "We're all one army. This war is a great test for Serbs. Those who pass the test will become winners. Deserters cannot go unpunished. Not a single Ustaša must leave Vukovar alive."[66]

Phase I, August to September 1991

The Battle of Vukovar took place in two phases over about 90 days: from August to September 1991, before the town was fully surrounded, and from early October to mid-November, when the town was encircled then taken by the JNA.[53] Starting in June, Vukovar and neighbouring villages were subjected to daily or near-daily artillery and mortar fire.[40] In July, the JNA and TO began deploying in large numbers across eastern Slavonia, surrounding Vukovar from three sides.[53] Heavy fighting began at the end of August. On 23 August, Borovo Naselje came under heavy shellfire, and Croatian forces shot down two Yugoslav G-2 Galeb fighter aircraft using shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles. The following day, the JNA, the Yugoslav Air Force and the Yugoslav Navy launched a major attack using aircraft, naval vessels on the Danube, tanks and artillery. The attack, which was mounted from both sides of the border, caused extensive damage and resulted in many civilian casualties.[40]

On 14 September, the Croatian government ordered an attack against all JNA garrisons and arms depots in the country, an offensive dubbed the Battle of the Barracks. Vukovar's JNA barracks was among those attacked that day, but the JNA managed to defend it. In retaliation, Serb paramilitaries attacked areas to the southwest of Vukovar from the direction of Negoslavci, forcing about 2,000 people to flee. There were reports of mass killings and scores of civilian deaths.[67] Croatian forces outside the Vukovar perimeter received large quantities of arms and ammunition from depots captured elsewhere, enabling them to hold the line.[53]

The JNA responded by launching a major offensive in eastern Slavonia, from where it intended to progress west via Vinkovci and Osijek to Zagreb. The JNA did not bypass Vukovar because its leadership wished to relieve the besieged barracks and to eliminate a possible threat to their supply lines. The JNA did not intend to make Vukovar the main focus of the offensive, but as happened with Stalingrad in the Second World War, an initially inconsequential engagement became an essential political symbol for both sides.[1]

On 19 September, a JNA force consisting of at least 100 T-55 and M-84 tanks with armoured personnel carriers and heavy artillery pieces left Belgrade. It crossed into Croatia near the Serbian town of Šid on 20 September.[68] The Croatians were quickly routed and fell back to Vukovar. The JNA's 1st Guards Mechanised Brigade soon reached the Vukovar barracks and lifted the Croatian siege of the facility. They also moved to encircle Vukovar. By 30 September, the town was almost completely surrounded. All roads in and out were blocked, and the only route in was via a farm track through a perilously exposed cornfield.[69]

The JNA launched repeated assaults on Vukovar but failed to make any progress. Its armour, designed for combat in open country, was barely able to enter Vukovar's narrow streets. Support from regular infantry was lacking, and the TO's poorly trained and motivated troops were inadequate substitutes.[58] The JNA's soldiers appeared to have little understanding of how to conduct urban operations and its officers displayed slow and reactive decision-making on the ground.[70]

Croatian forces countered the JNA's attacks by mining approach roads, sending out mobile teams equipped with anti-tank weapons, deploying many snipers, and fighting back from heavily fortified positions.[58] The JNA initially relied on massing armoured spearheads which would advance along a street in a column followed by a few companies of infantry.[71] The Croatians responded by opening fire with anti-tank weapons at very close range – often as short as 20 metres (66 ft) – to disable the lead and rear vehicles, trapping the rest of the column, where it could be systematically disabled.[72] They tried to avoid completely destroying the JNA's armour, as the materiel they retrieved from disabled vehicles was an important source of resupply.[73] The Croatians employed a strategy of "active defence", carrying out hit-and-run attacks to keep the JNA off balance.[74] Anti-tank and anti-personnel mines hindered JNA manoeuvres. Unconventional tactics were used to undermine the JNA's morale, such as firing weather rockets[75] and sabotaging JNA tanks by planting mines underneath them while they were parked at night, causing them to explode when their crews started them in the morning.[76] JNA casualties were heavy. On one road, dubbed the "tank graveyard", about a hundred JNA armoured vehicles were destroyed, fifteen of them by Colonel Marko Babić.[77] The high casualties had a debilitating effect on morale all the way up the chain of command.[78]

The JNA began launching artillery and rocket barrages against the town. By the end of the battle, over 700,000 shells and other missiles had been fired at Vukovar[79] at a rate of up to 12,000 a day.[3] It is estimated that Vukovar as well as its surroundings were bombarded with more than 2.5 million shells over 20 millimetres (0.79 in).[80] Metre for metre, the bombardment was more intense than at Stalingrad.[51] The thousands of civilians remaining in Vukovar took shelter in cellars and bomb shelters that had been built during the Cold War.[69]

JNA weaknesses and adoption of new tactics

The JNA's lack of infantry support was due to a disastrously low level of mobilisation in the preceding months. Many reservists – who were drawn from all the Yugoslav republics, including Croatia – refused to report for duty, and many serving soldiers deserted rather than fight.[81] Serbia was never formally at war and no general mobilisation was carried out.[82] An estimated 150,000 Serbs went abroad to avoid conscription, and many others deserted or went into hiding.[83] Only 13 percent of conscripts reported for duty.[84] Another 40,000 staged rebellions in towns across Serbia; the Serbian newspaper Vreme commented in July 1991 that the situation was one of "total military disintegration".[85]

Morale on the battlefield was poor. JNA commanders resorted to firing on their own positions to motivate their men to fight. When the commander of a JNA unit at Vukovar demanded to know who was willing to fight and who wanted to go home, the unit split in two. One conscript, unable to decide which side to take, shot himself on the spot.[86] A JNA officer who served at Vukovar later described how his men refused to obey orders on several occasions, "abandoning combat vehicles, discarding weapons, gathering on some flat ground, sitting and singing Give Peace a Chance by John Lennon." In late October, an entire infantry battalion from Novi Sad in Serbia abandoned an attack on Borovo Naselje and fled. Another group of reservists threw away their weapons and went back to Serbia on foot across a nearby bridge.[87] A tank driver, Vladimir Živković, drove his vehicle from the front line at Vukovar to the Yugoslav parliament in Belgrade, where he parked on the steps in front of the building. He was arrested and declared insane by the authorities. His treatment enraged his colleagues, who protested by taking over a local radio station at gunpoint and issuing a declaration that "we are not traitors, but we do not want to be aggressors."[88]

In late September, Lieutenant Colonel General Života Panić was put in charge of the operation against Vukovar. He established new headquarters and command-and-control arrangements to resolve the disorganisation that had hindered the JNA's operations. Panić divided the JNA forces into Northern and Southern Areas of Responsibility (AORs). The northern AOR was assigned to Major General Mladen Bratić, while Colonel Mile Mrkšić was given charge of the south.[89] As well as fresh troops, paramilitary volunteers from Serbia were brought in. They were well armed and highly motivated but often undisciplined and brutal. They were formed into units of company and battalion size as substitutes for the missing reservists.[58] The commander of the Novi Sad corps was videotaped after the battle praising the Serb Volunteer Guard ("Tigers") of Željko Ražnatović, known as "Arkan":[90]

The greatest credit for this goes to Arkan's volunteers! Although some people accuse me of acting in collusion with paramilitary formations, these are not paramilitary formations here! They are men who came voluntarily to fight for the Serbian cause. We surround a village, he dashes in and kills whoever refuses to surrender. On we go![90]

Panić combined well-motivated paramilitary infantry with trained engineering units to clear mines and defensive positions, supported by heavy armour and artillery.[91] The paramilitaries spearheaded a fresh offensive that began on 30 September. The assault succeeded in cutting the Croatian supply route to Vukovar when the village of Marinci, on the route out of the town, was captured on 1 October. Shortly afterwards, the Croatian 204th Brigade's commander, Mile Dedaković, broke out with a small escort, slipping through the Serbian lines to reach the Croatian-held town of Vinkovci. His deputy, Branko Borković, took over command of Vukovar's defences. General Anton Tus, commander of the Croatian forces outside the Vukovar perimeter, put Dedaković in charge of a breakthrough operation to relieve the town and launched a counter-offensive on 13 October.[58][92] Around 800 soldiers and 10 tanks were engaged in the attack, which began in the early morning with artillery preparation. Special police forces entered Marinci before noon, but had to retreat as they did not have enough strength to hold their positions. Croatian tanks and infantry encountered heavy resistance from the JNA and were halted at Nuštar by artillery fire. The JNA's 252nd Armoured Brigade inflicted heavy losses on the Croatian forces and around 13:00 the attack was stopped by the HV General Staff. A humanitarian convoy of the Red Cross was let through to Vukovar.[93]

Phase II, October to November 1991

During the battle's final phase, Vukovar's remaining inhabitants, including several thousand Serbs, took refuge in cellars and communal bomb shelters, which housed up to 700 people each. A crisis committee was established, operating from a nuclear bunker beneath the municipal hospital. The committee assumed control of the town's management and organised the delivery of food, water and medical supplies. It kept the number of civilians on the streets to a minimum and ensured that each shelter was guarded and had at least one doctor and nurse assigned to it.[94]

Vukovar's hospital had to deal with hundreds of injuries. In the second half of September, the number of wounded reached between 16 and 80 per day, three-quarters of them civilians.[67] Even though it was marked with the Red Cross symbol, the hospital was struck by over 800 shells during the battle. Much of the building was wrecked, and the staff and patients had to relocate to underground service corridors. The intensive care unit was moved into the building's nuclear bomb shelter.[3] On 4 October, the Yugoslav Air Force attacked the hospital, destroying its operating theatre. One bomb fell through several floors, failed to explode and landed on the foot of a wounded man, without injuring him.[67]

Croatian forces adapted several Antonov An-2 biplanes to parachute supplies to Vukovar. The aircraft also dropped improvised bombs made of fuel cans and boilers filled with explosive and metal bars.[95] The crews used GPS to locate their targets, then pushed the ordnance through the side door.[96]

The European Community attempted to provide humanitarian aid to the 12,000 civilians trapped within the perimeter, but only one aid convoy made it through.[97] On 12 October, the Croatians suspended military action to allow the convoy to pass, but the JNA used the pause as cover to make further military gains. Once the convoy set off, the JNA delayed it for two days and used the time to lay mines, bring in reinforcements and consolidate JNA control of the road out of Vukovar.[98] When the convoy arrived, it delivered medical supplies to Vukovar's hospital and evacuated 114 wounded civilians.[97]

On 16 October, the JNA mounted a major attack against Borovo Naselje. It made some progress, but became bogged down in the face of determined Croatian resistance.[58] On 30 October, the JNA launched a fully coordinated assault, spearheaded by paramilitary forces, with infantry and engineering troops systematically forcing their way past the Croatian lines. The JNA's forces, divided into northern and southern operations sectors, attacked several points simultaneously and pushed the Croatians back.[91] The JNA also adopted new tactics, such as firing directly into houses and then driving tanks through them, as well as using tear gas and smoke bombs to drive out those inside. Buildings were also captured with the use of anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns.[99]

On 2 November, the JNA reached the strategic suburb of Lužac, between Borovo Naselje and Vukovar, cutting one of the two roads linking the town centre with its northern suburb.[100] Meanwhile, the ZNG (which had been renamed the Croatian Army) attempted to retake the villages of Marinci and Cerić to reopen the supply route to Vukovar. It mounted a heavy bombardment of the JNA's access routes to Vukovar and launched a tank attack on the JNA's lines. On 4 November, JNA General Mladen Bratić was killed when his tank was hit by a shell.[54] The JNA's advantage in artillery and rockets enabled it to halt the Croatian advance and inflict heavy casualties.[54]

Fall of Vukovar

JNA troops launched an amphibious assault across the Danube north of Lužac on 3 November to link up with Arkan's "Tigers". This attack split the Croatian perimeter in half and divided the main group of defenders in the town centre from a smaller stronghold in Borovo Naselje. The JNA's Operational Group South began systematically clearing the town centre, cutting off the remaining Croatian soldiers.[91] On 5 November, Croatian forces shelled the Serbian town of Šid, killing three civilians and wounding several others.[101] The JNA and paramilitaries captured a key hilltop, Milova Brda,[100] on 9 November, giving them a clear view of Vukovar. The assault was spearheaded by paramilitaries, with JNA soldiers and TO fighters playing a supporting role, especially in demining operations and close artillery support.[91] The Croatian-held village of Bogdanovci, just west of Vukovar, fell on 10 November.[100] As many as 87 civilians were killed after its capture.[102]

On 13 November, the JNA cut the last link between Borovo Naselje and Vukovar. Croatian forces outside the Vukovar perimeter mounted a last-ditch attempt to break the siege by attacking from the village of Nuštar, but were repelled by the JNA once again. By now, the Croatians were running out of ammunition and were exhausted from fighting around the clock without any prospect of relief.[100] They had been reduced to three separate pockets. With defeat now inevitable, several hundred Croatian soldiers and civilians attempted to break out over the course of several days, as the JNA mounted its final offensive.[100] Most of those in Borovo Naselje were unable to do so and were killed.[54]

On 18 November, the last Croatian soldiers in Vukovar's town centre surrendered.[91] By 18 November, many of Vukovar's civilian inhabitants were living in squalid conditions and nearing starvation. One woman told UN Special Envoy Cyrus Vance that she had spent the two previous months in a bomb shelter with her five children without toilets or water for washing. They lived on two slices of bread and a piece of pâté per day.[103] One of the Croatian soldiers described conditions as the battle reached its peak:

By early October, there were no cigarettes. People were smoking grape leaves or tea. There was no yeast for bread. My son was eating tinned food with me and my wife. There was less and less of that. The shelling became 24 hours a day, and the cease-fires were worse. When people came out of the shelters to go to the well during the cease-fires, the snipers shot them. You can't keep children in for two months, and when they ran outside, when there was sun in the morning, they shot at them, too.[104]

When the battle ended, the scale of the town's destruction shocked many who had not left their shelters in weeks. Siniša Glavašević, a reporter for Croatian Radio and a native of Vukovar, who had stayed in the town throughout the battle, described the scene as the survivors emerged:

The picture of Vukovar at the 22nd hour of the 87th day [of the siege] will stay forever in the memory of those who witnessed it. Unearthly scenes are endless, the smell of burning, under the feet the remnants of old roof tiles, building materials, glass, ruins, and a dreadful silence. ... We hope that the torments of Vukovar are over.[105]

Although active combat had ended in central Vukovar by 18 November, sporadic fighting continued for several days elsewhere in the town. Some Croatian soldiers continued to resist until 20 November and a few managed to slip away from Borovo Naselje as late as 23 November.[100] Foreign journalists and international monitors entered the town soon after the surrender and recorded what they saw. Blaine Harden of The Washington Post'' wrote:

Not one roof, door or wall in all of Vukovar seems to have escaped jagged gouges or gaping holes left by shrapnel, bullets, bombs or artillery shells – all delivered as part of a three-month effort by Serb insurgents and the Serb-led Yugoslav army to wrest the city from its Croatian defenders. Not one building appears habitable, or even repairable. Nearly every tree has been chopped to bits by firepower.[106]

Chuck Sudetic of The New York Times reported:

Only soldiers of the Serbian-dominated army, stray dogs and a few journalists walked the smoky, rubble-choked streets amid the ruins of the apartment buildings, stores and hotel in Vukovar's center. Not one of the buildings seen during a daylong outing could be described as habitable. In one park, shell fire had sheared thick trees in half like blades of grass cut by a mower. Across the street, the dome of an Orthodox Christian church had fallen onto the altar. Automatic weapons fire erupted every few minutes as the prowling Serbian soldiers, some of them drunk, took aim at land mines, pigeons and windows that had survived the fighting.[107]

Laura Silber and the BBC's Allan Little described how "corpses of people and animals littered the streets. Grisly skeletons of buildings still burned, barely a square inch had escaped damage. Serbian volunteers, wild-eyed, roared down the streets, their pockets full of looted treasures."[108] The JNA celebrated its victory, as Marc Champion of The Independent described:

The colonels who ran "Operation Vukovar" entertained more than 100 journalists inside the ruins of the Dunav Hotel at a kind of Mad Hatter's victory celebration. They handed out picture postcards of the old Vukovar as mementoes and served drinks on starched white tablecloths, as wind and rain blew in through shattered windows ... Inside the Dunav Hotel was an Alice in Wonderland world where Colonel [Miodrag] Gvero announced that the gaping holes in the walls had been blasted by the Croatian defenders. They had placed sticks of dynamite in the brickwork to make the army look bad, he said.[109]

Casualties

Overall, around 3,000 people died during the battle.[110] Croatia suffered heavy military and civilian casualties. The Croatian side initially reported 1,798 killed in the siege, both soldiers and civilians.[18] Croatian general Anton Tus later stated that about 1,100 Croatian soldiers were killed, and 2,600 soldiers and civilians were listed as missing. Another 1,000 Croatian soldiers were killed on the approaches to Vinkovci and Osijek, according to Tus. He noted that the fighting was so intense that losses in eastern Slavonia between September and November 1991 constituted half of all Croatian war casualties from that year.[54] According to figures published in 2006 by the Croatian Ministry of Defence, 879 Croatian soldiers were killed and 770 wounded in Vukovar.[111] The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) estimates Croatian casualties at around 4,000–5,000 dead across eastern Slavonia as a whole. The 204th Vukovar Brigade lost over 60 percent of its strength in the battle.[91] The CIA reports that 1,131 civilians were killed over the course of the fighting.[112] Among the dead were 86 children.[113] According to Croatian officials, in eastern Slavonia, 2,000 Croatians were killed, 800 went missing, 3,000 were taken prisoner and 42,852 were made refugees by the end of 1991.[114]

Although JNA losses were undoubtedly substantial, the exact numbers are unclear because of a lack of official data. The JNA officially acknowledged 1,279 killed in action, including 177 officers, during the entire war in Croatia. The military historian Norman Cigar contends that the actual number may have been considerably greater as casualties were consistently under-reported during the war.[115] According to Tus, the JNA's Novi Sad corps alone lost 1,300 soldiers during the campaign in eastern Slavonia. He extrapolates from this to estimate that between 6,000 and 8,000 soldiers and volunteers died in eastern Slavonia, with the loss of 600 armoured vehicles and heavy weapons, as well as over 20 aircraft.[54]

Serbian sources disagree with this assessment. Following the war, Colonel Milisav Sekulić said that the battle resulted in the deaths of 1,180 JNA soldiers and TO personnel.[116] General Andrija Biorčević, the former commander of the Novi Sad corps, remarked that there were "[not] more than 1,500 killed on our side."[117] This sentiment was echoed by JNA General Života Panić, who shared a similar figure.[118] In 1997, the journalist Miroslav Lazanski, who has close ties to the Serbian military, wrote in the Belgrade newspaper Večernje novosti that "on the side of the JNA, Territorial Defence and volunteer units, exactly 1,103 members were killed." He cited losses of 110 armoured vehicles and two combat aircraft shot down, plus another destroyed due to technical failure. At the time, Lazanski's assessment was endorsed by three retired JNA generals.[117] According to Croatian Serb sources, 350 Vukovar Serbs perished in the battle, including 203 TO fighters and 147 civilians.[119]

War crimes

Many captured Croatian soldiers and civilians were summarily executed after the battle. Journalists witnessed one such killing in Vukovar's main street.[107] They also reported seeing the streets strewn with bodies in civilian attire.[120] BBC television reporters recorded Serbian paramilitaries chanting: "Slobodane, Slobodane, šalji nam salate, biće mesa, biće mesa, klaćemo Hrvate!" ("Slobodan [Milošević], Slobodan, send us some salad, [for] there will be meat, there will be meat, we will slaughter Croats").[121] A Serbian journalist embedded with the JNA reserve forces in Vukovar later reported:

After Vukovar fell, people were lined up and made to walk to detention areas. As the prisoners walked by, local Serbian paramilitaries pulled people out of the lines at random, claiming that they had to be executed because they were "war criminals." Most of these people were Croats who had spent the duration of the fighting in basements, particularly in the Vukovar hospital. The selection of those who were to be executed also was done as these people were leaving the shelters. They were removed from lines under the supervision, and with the apparent permission, of Major Veselin Šljivančanin, the JNA officer in charge of security after Vukovar's fall.[122]

Around 400 people from Vukovar's hospital – non-Serb patients, medical personnel, local political figures and others who had taken refuge there – were taken by the JNA. Although some were subsequently released, around 200 were transported to the nearby Ovčara farm and executed in what became known as the Vukovar massacre. At least 50 others were taken elsewhere and never seen again.[123] Thousands more were transferred to prison camps in Serbia and rebel-controlled Croatia. Further mass killings followed. At Dalj, north of Vukovar, where many inhabitants were previously massacred, numerous prisoners from Vukovar were subjected to harsh interrogations, beatings and torture, and at least 35 were killed.[124] The JNA imprisoned 2,000 people at the Velepromet industrial facility in Vukovar, 800 of whom were classified by the JNA as prisoners of war. Many were brutally interrogated, several were shot on the spot by TO members and paramilitaries, and others were sent to Ovčara, where they were killed in the massacre. The remaining prisoners were transferred to a JNA-run prison camp in Sremska Mitrovica.[125][126] They were stripped naked on arrival, beaten and interrogated, and forced to sleep for weeks on bare wooden floors. Most were released in January 1992 under an agreement brokered by UN envoy Cyrus Vance.[108] Others were kept prisoner until mid-1992.[127] Serbs who fought on the Croatian side were regarded as traitors by their captors and treated particularly harshly, enduring savage beatings.[47]

Detainees who were not suspected of involvement in military activities were evacuated from Vukovar to other locations in Serbia and Croatia.[125] The non-Serb population of the town and the surrounding region was systematically ethnically cleansed, and at least 20,000 of Vukovar's inhabitants were forced to leave, adding to the tens of thousands already expelled from across eastern Slavonia.[6] About 2,600 people went missing as a result of the battle.[128] As of November 2017[update], the whereabouts of more than 440 of these individuals are unknown.[129] There were also incidents of war rape, for which two soldiers were later convicted.[130][131][132]

Serb forces singled out a number of prominent individuals. Among them was Dr. Vesna Bosanac, the director of the town's hospital,[133] who was regarded as a heroine in Croatia but demonised by the Serbian media.[108][134] She and her husband were taken to Sremska Mitrovica prison, where she was locked up in a single room with more than 60 other women for several weeks. Her husband was subjected to repeated beatings. After appeals from the International Committee of the Red Cross,[108] the couple were eventually released in a prisoner exchange.[133] The journalist Siniša Glavašević was taken to Ovčara, severely beaten and shot along with the other victims of the massacre.[135][108]

Vukovar was systematically looted after its capture. A JNA soldier who fought at Vukovar told the Serbian newspaper Dnevni Telegraf that "the Chetnik [paramilitaries] behaved like professional plunderers, they knew what to look for in the houses they looted."[136] The JNA also participated in the looting; an official in the Serbian Ministry of Defence commented: "Tell me of even one reservist, especially if he is an officer, who has spent more than a month at the front and has not brought back a fine car filled with everything that would fit inside the car."[137] More than 8,000 works of art were looted during the battle, including the contents of the municipal museum, Eltz Castle, which was bombed and destroyed during the siege.[138] Serbia returned 2,000 pieces of looted art in December 2001.[139]

Indictments and trials

Three JNA officers – Mile Mrkšić, Veselin Šljivančanin and Miroslav Radić – were indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) on multiple counts of crimes against humanity and violations of the laws of war, having surrendered or been captured in 2002 and 2003. On 27 September 2007, Mrkšić was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment on charges of murder and torture, Šljivančanin was sentenced to five years' imprisonment for torture and Radić was acquitted.[140] Šljivančanin's sentence was increased to 17 years on appeal.[141] It was reduced to ten years after a second appeal and he was granted early release in July 2011.[142] Slavko Dokmanović, the Serb mayor of Vukovar, was also indicted and arrested for his role in the massacre, but committed suicide in June 1998, shortly before judgement was to be passed.[143]

Serbian paramilitary leader Vojislav Šešelj was indicted on war crimes charges, including several counts of extermination, for the Vukovar hospital massacre, in which his "White Eagles" were allegedly involved.[144] In March 2016, Šešelj was acquitted on all counts pending appeal.[145] On 11 April 2018, the Appeals Chamber of the follow-up Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals convicted him of crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 10 years' imprisonment for a speech delivered in May 1992 in which he called for the expulsion of Croats from Vojvodina. He was acquitted of the war crimes and crimes against humanity that he was alleged to have committed elsewhere, including in Vukovar.[146]

The ICTY's indictment of Slobodan Milošević characterised the overall JNA and Serb offensive in Croatia – including the fighting in eastern Slavonia – as a "joint criminal enterprise" to remove non-Serb populations from Serb-inhabited areas of Croatia. Milošević was charged with numerous crimes against humanity, violations of the laws of war, and breaches of the Geneva Conventions in relation to the battle and its aftermath.[6] He died in March 2006, before his trial could be completed.[147] The Croatian Serb leader Goran Hadžić was indicted for "wanton destruction of homes, religious and cultural buildings" and "devastation not justified by military necessity" across eastern Slavonia, and for deporting Vukovar's non-Serb population.[148] He was arrested in July 2011, after seven years on the run, and pleaded not guilty to 14 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity.[149] He died in July 2016, before his trial could be completed.[150]

In December 2005, a Serbian court convicted 14 former paramilitaries for their involvement in the hospital massacre.[151] In 2011, a Serbian court indicted more than 40 Croatians for alleged war crimes committed in Vukovar.[152] An earlier indictment against a Croatian soldier was dropped because of irregularities in the investigation.[153] Croatia also indicted a number of Serbs for war crimes committed in Vukovar,[154] including former JNA generals Veljko Kadijević and Blagoje Adžić.[155] Adžić died of natural causes in Belgrade in March 2012 and never faced trial.[156] Kadijević fled Yugoslavia following Milošević's overthrow and sought asylum in Russia. He was granted Russian citizenship in 2008 and died in Moscow in November 2014.[157] In 1999, Croatia sued Yugoslavia before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming that genocide had been committed in Vukovar. Following Serbia and Montenegro's dissolution in 2006, this suit was passed on to Serbia. In February 2015, the ICJ ruled that the battle and ensuing massacre did not constitute genocide, but affirmed that serious crimes had been committed by the JNA and Serb paramilitaries.[158][159]

Political aspects

Propaganda

The Serbian and Croatian media waged a fierce propaganda struggle over the progress of the battle and the reasons behind it. Both sides' propaganda machines aimed to promote ultra-nationalist sentiments and denigrate the other side with no pretence of objectivity or self-criticism. The Croatian media described the Serbian forces as "Serb terrorists" and a "Serbo-Communist army of occupation" intent on crushing the thousand-year dream of an independent Croatia.[160] The propaganda reached peak intensity in the wake of Vukovar's fall. The Croatian newspaper Novi list denounced the Serbs as "cannibals" and "brutal Serb extremists". The Serbian media depicted the JNA and Serbian forces as "liberators" and "defenders" of the Serbian people, and the Croatian forces as "Ustashoid hordes", "blackshirts", "militants" and "drunk and stoned monsters". There were overt appeals to racial and gender prejudice, including claims that Croatian combatants had "put on female dress to escape from the town" and had recruited "black men".[161]

Victim status became a central aim for the propaganda machines of both sides, and the battle was used to support claims of atrocities. Victims became interchangeable as anonymous victims were identified as Croats by the Croatian media and as Serbs by the Serbian media. According to the Serbian opposition periodical Republika, the state-owned station TV Novi Sad was under orders to identify any bodies its reporters filmed as being "Serbian corpses".[162] After the battle, Belgrade television showed pictures of hundreds of corpses lined up outside Vukovar's hospital and claimed that they were Serbs who had been "massacred" by the Croats. According to Human Rights Watch, the bodies belonged to those who had died of their injuries at the hospital, whose staff had been prevented from burying them by the intense Serbian bombardment, and had been forced to leave them lying in the open. Serbian television continued to broadcast claims of "massacred Serbs in Vukovar" for some time after the town's fall.[163]

Such victim-centred propaganda had a powerful motivating effect. One Serbian volunteer said that he had never seen the town before the war, but had come to fight because "the Croats had a network of catacombs under the city where they killed and tortured children just because they were Serbs."[164] Reuters erroneously reported that 41 children had been massacred in Vukovar by Croatian soldiers. Although the claim was retracted a day later, it was used by the Serbian media to justify military action in Croatia.[165] Many of those fighting at Vukovar believed that they were engaged in a struggle to liberate the town from a hostile occupier.[166]

International reaction

The international community made repeated unsuccessful attempts to end the fighting. Both sides violated ceasefires, often within hours. Calls by some European Community members for the Western European Union to intervene militarily were vetoed by the British government. Instead, a Conference for Yugoslavia was established under the chairmanship of Lord Carrington to find a way to end the conflict. The United Nations (UN) imposed an arms embargo on all of the Yugoslav republics in September 1991 under Security Council Resolution 713, but this was ineffective, in part because the JNA had no need to import weapons. The European powers abandoned attempts to keep Yugoslavia united and agreed to recognise the independence of Croatia and Slovenia on 15 January 1992.[167]

International observers tried unsuccessfully to prevent the human rights abuses that followed the battle. A visit by UN envoys Marrack Goulding and Cyrus Vance was systematically obstructed by the JNA. Vance's demands to see the hospital, from which wounded patients were being dragged out to be killed, were rebuffed by one of the massacre's chief architects, Major Veselin Šljivančanin.[168] The major also blocked Red Cross representatives in an angry confrontation recorded by TV cameras: "This is my country, we have conquered this. This is Yugoslavia, and I am in command here!"[169]

There was no international media presence in Vukovar, as there was in the simultaneous Siege of Dubrovnik and the subsequent Siege of Sarajevo, and relatively little of the fighting in Vukovar was broadcast to foreign audiences. The British journalist Misha Glenny commented that the JNA, the Croatian Serb government and many ordinary Serbs were often hostile to the foreign media, while the Croatians were more open and friendly.[170]

Croatian reaction

The Croatian media gave heavy coverage to the battle, repeatedly airing broadcasts from the besieged town by the journalist Siniša Glavašević. Much popular war art focused on the "VukoWAR", as posters dubbed it.[171] The Croatian government began suppressing Glavašević's broadcasts when it became clear that defeat was inevitable,[171] despite the confident slogans of "Vukovar shall not fall" and "Vukovar must not fall." Two of the main daily newspapers, Večernji list and Novi list, failed to report the loss of Vukovar and, on 20 November, two days after it had fallen, repeated the official line that the fight was still continuing. News of the surrender was dismissed as Serbian propaganda.[172] Many Croatians soon saw Western satellite broadcasts of JNA soldiers and Serb paramilitaries walking freely through the town and detaining its inhabitants.[173] When the surrender could no longer be denied, the two newspapers interpreted the loss as a demonstration of Croatian bravery and resistance, blaming the international community for not intervening to help Croatia.[172]

The Croatian government was criticised for its approach to the battle.[172] Surviving defenders and right-wing politicians accused the government of betraying and deliberately sacrificing Vukovar to secure Croatia's international recognition. The only explanation that many were willing to accept for the town's fall was that it had been given up as part of a conspiracy.[174] The Croatian commanders in Vukovar, Mile Dedaković and Branko Borković, both survived the battle and spoke out publicly against the government's actions. In an apparent attempt to silence them, both men were briefly detained by the Croatian military police.[91] The Croatian government also suppressed an issue of the newspaper Slobodni tjednik that published a transcript of a telephone call from Vukovar, in which Dedaković had pleaded with an evasive Tuđman for military assistance. The revelations caused public outrage and reinforced perceptions that the defenders had been betrayed.[175]

From a military point of view, the outcome at Vukovar was not a disaster for Croatia's overall war effort. The battle broke the back of the JNA, leaving it exhausted and unable to press deeper into the country. Vukovar was probably indefensible, being almost completely surrounded by Serb-held territory and located closer to Belgrade than to Zagreb. Although the defeat was damaging to Croatian morale, in a strategic context, the damage and delays inflicted on the JNA more than made up for the loss of the town.[91]

Following the battle, Vukovar became a symbol of Croatian resistance and suffering. The survivors, veterans and journalists wrote numerous memoirs, songs and testimonies about the battle and its symbolism, calling it variously "the phenomenon", "the pride", "the hell" and "the Croatian knight". Writers appealed to the "Vukovar principle", the "spirituality of Vukovar" and "Vukovar ethics", the qualities said to have been exhibited by the defenders and townspeople.[174] Croatian war veterans were presented with medals bearing the name of Vukovar.[176] In 1994, when Croatia replaced the Croatian dinar with its new currency, the kuna, it used the destroyed Eltz Castle in Vukovar and the Vučedol Dove – an artefact from an ancient Neolithic culture centred on eastern Slavonia, which was discovered near Vukovar – on the new twenty-kuna note. The imagery emphasised the Croatian nature of Vukovar, which at the time was under Serb control.[177] In 1993 and 1994, there was a national debate on how Vukovar should be rebuilt following its reintegration into Croatia, with some Croatians suggesting that it should be preserved as a monument.[176]

The ruling HDZ made extensive use of popular culture relating to Vukovar as propaganda in the years before the region was reintegrated into Croatia.[178] In 1997, President Tuđman mounted a tour of eastern Slavonia, accompanied by a musical campaign called Sve hrvatske pobjede za Vukovar ("All Croatian victories for Vukovar"). The campaign was commemorated by the release of a compilation of patriotic music from Croatia Records.[179] When Vukovar was returned to Croatian control in 1998, its recovery was hailed as the completion of a long struggle for freedom and Croatian national identity.[180] Tuđman alluded to such sentiments when he gave a speech in Vukovar to mark its reintegration into Croatia:

Our arrival in Vukovar – the symbol of Croatian suffering, Croatian resistance, Croatian aspirations for freedom, Croatian desire to return to its eastern borders on the Danube, of which the Croatian national anthem sings – is a sign of our determination to really achieve peace and reconciliation.[180]

Serbian reaction

Although the battle had been fought in the name of Serbian defence and unity, reactions in Serbia were deeply divided. The JNA, the state-controlled Serbian media and Serbian ultra-nationalists hailed the victory as a triumph. The JNA even erected a triumphal arch in Belgrade through which its returning soldiers could march, and officers were congratulated for taking "the toughest and fiercest Ustaša fortress".[181] The Serbian newspaper Politika ran a front-page headline on 20 November announcing: "Vukovar Finally Free".[169] In January 1992, from the ruins of Vukovar, the ultranationalist painter Milić Stanković wrote an article for the Serbian periodical Pogledi ("Viewpoints"), in which he declared: "Europe must know Vukovar was liberated from the Croat Nazis. They were helped by Central European scum. They crawled from under the papal tiara, as a dart of the serpent's tongue that protruded from the bloated Kraut and overstretched Eurocommunal anus."[182]

The Serbian geographer Jovan Ilić set out a vision for the future of the region, envisaging it being annexed to Serbia and its expelled Croatian population being replaced with Serbs from elsewhere in Croatia. The redrawing of Serbia's borders would unite all Serbs in a single state, and would cure Croats of opposition to Serbian nationalism, which Ilić termed an "ethno-psychic disorder". Thus, Ilić argued, "the new borders should primarily be a therapy for the treatment of ethno-psychic disorders, primarily among the Croatian population." Other Serbian nationalist writers acknowledged that the historical record showed that eastern Slavonia had been inhabited by Croats for centuries, but accused the region's Croat majority of "conversion to Catholicism, Uniating and Croatisation", as well as "genocidal destruction". Most irredentist propaganda focused on the region's proximity to Serbia and its sizeable Serb population.[183]

The Croatian Serb leadership also took a positive view of the battle's outcome. Between 1991 and 1995, while Vukovar was under the control of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), the city's fall was officially commemorated as "Liberation Day". The battle was portrayed as a successful struggle by local Serbs to defend their lives and property from the aggression of the Croatian state. Thousands of Vukovar Serbs that had suffered alongside their Croatian neighbours, sheltering in basements or bomb shelters for three months in appalling conditions, were now denigrated as podrumaši, the "people from the basement". Serb civilian dead were denied recognition, and the only people buried in the Serbian memorial cemetery at Vukovar were local Serbs who had fought with or alongside the JNA.[184]

In contrast, many in Serbia were strongly opposed to the battle and the wider war, and resisted efforts by the state to involve them in the conflict.[185] Multiple anti-war movements appeared in Serbia as Yugoslavia began to disintegrate. In Belgrade, sizeable anti-war protests were organized in opposition to the battle. The protesters demanded that a referendum be held on a formal declaration of war, as well as an end to conscription.[186] When the JNA tried to call up reservists, parents and relatives gathered around barracks to prevent their children taking part in the operation.[185] Resistance to conscription became widespread across Serbia, ranging from individual acts of defiance to collective mutinies by hundreds of reservists at a time. A number of Serbian opposition politicians condemned the war. Desimir Tošić of the Democratic Party accused Milošević of "using the conflict to cling to power", and Vuk Drašković, the leader of the Serbian Renewal Movement, appealed to JNA soldiers to "pick up their guns and run".[187] After the fall of Vukovar, he condemned what had been done in the name of Yugoslavia, writing in the daily newspaper Borba:

I cannot applaud the Vukovar victory, which is so euphorically celebrated in the war propaganda of intoxicated Serbia. I cannot, for I won't violate the victims, thousands of dead, nor the pain and misfortune of all Vukovar survivors ... [Vukovar] is the Hiroshima of both Croatian and Serbian madness ... Everyone in this state, Serbs but especially Croats, have established days of the greatest shame and fall.[188]

By late December 1991, just over a month after victory had been proclaimed in Vukovar, opinion polls found that 64 percent wanted to end the war immediately and only 27 percent were willing for it to continue. Milošević and other senior Serbian leaders decided against continuing the fighting, as they saw it as politically impossible to mobilise more conscripts to fight in Croatia. Desertions from the JNA continued as the well-motivated and increasingly well-equipped Croatian Army became more difficult to counter. By the end of 1991, Serbia's political and military leadership concluded that it would be counter-productive to continue the war. The looming conflict in Bosnia also required that the military resources tied up in Croatia be freed for future use.[189]

Although the battle was publicly portrayed as a triumph, it profoundly affected the JNA's character and leadership behind the scenes. The army's leaders realised that they had overestimated their ability to pursue operations against heavily defended urban targets, such as the strategic central Croatian town of Gospić, which the JNA assessed as potentially a "second Vukovar". The "Serbianisation" of the army was greatly accelerated, and, by the end of 1991, it was estimated to be 90 percent Serb. Its formerly pro-communist, pan-Yugoslav identity was abandoned, and new officers were now advised to "love, above all else, their unit, their army and their homeland – Serbia and Montenegro". The JNA's failure enabled the Serbian government to tighten its control over the military, whose leadership was purged and replaced with pro-Milošević nationalists. After the battle, General Veljko Kadijević, commander of the JNA, was forced into retirement for "health reasons", and in early 1992, another 38 generals and other officers were forced to retire, with several put on trial for incompetence and treason.[190]

Many individual JNA soldiers who took part in the battle were revolted by what they had seen and protested to their superiors about the behaviour of the paramilitaries. Colonel Milorad Vučić later commented that "they simply do not want to die for such things". The atrocities that they witnessed led some to experience subsequent feelings of trauma and guilt. A JNA veteran told a journalist from the Arabic-language newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat:

'I was in the Army and I did my duty. Vukovar was more of a slaughter than a battle. Many women and children were killed. Many, many.' I asked him: 'Did you take part in the killing?' He answered: 'I deserted.' I asked him: 'But did you kill anyone?' He replied: 'I deserted after that ... The slaughter of Vukovar continues to haunt me. Every night I imagine that the war has reached my home and that my own children are being butchered.'[137]

Other Yugoslav reaction

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, President Alija Izetbegović made a televised appeal to Bosnian citizens to refuse the draft on the grounds that "this is not our war". He called it their "right and duty" to resist the "evil deeds" being committed in Croatia and said: "Let those who want it, wage it. We do not want this war."[96] When JNA troops transferred to the front via the Višegrad region of north-eastern Bosnia, local Bosnian Croats and Muslims set up barricades and machine-gun posts. They halted a column of 60 JNA tanks but were dispersed by force the following day. More than 1,000 people had to flee the area. This action, nearly seven months before the start of the Bosnian War, caused the first casualties of the Yugoslav Wars in Bosnia.[191]

Macedonia's parliament adopted a declaration of independence from Yugoslavia in January 1991, but it did not take effect until a referendum in September 1991 confirmed it. A group of Macedonian JNA officers secretly sought to prevent soldiers from Macedonia being sent to Croatia, and busloads of soldiers' parents, funded by the Macedonian government, travelled to Montenegro to find their sons and bring them home.[192] Meanwhile, Macedonians continued to be conscripted into the JNA and serve in the war in Croatia.[192] The commander of JNA forces in the first phase of the battle, General Aleksandar Spirkovski, was a Macedonian. His ethnicity was probably a significant factor in the decision to replace him with Života Panić, a Serb.[41] In 2005, the Macedonian Army's Chief of Staff, General Miroslav Stojanovski, became the focus of international controversy after it was alleged that he had been involved in possible war crimes following the battle.[193]

Occupation, restoration and reconstruction

Vukovar suffered catastrophic damage in the battle. Croatian officials estimated that 90 percent of its housing stock was damaged or destroyed,[114] accounting for 15,000 housing units in total.[194] The authorities placed the cost of reconstruction at $2.5 billion.[195] The town barely recovered during its seven years under Serb control.[196] Marcus Tanner of The Independent described post-battle Vukovar as:

a silent, ghostly landscape, consisting of mile upon mile of bricks, rusting cars, collapsed roofs, telegraph poles and timber beams poking out from the rubble. The wind whistles through the deserted warehouses along the river front. By next spring, grass and saplings will be sprouting and birds nesting in these piles, and hope of rebuilding will be over.[197]

When Michael Ignatieff visited Vukovar in 1992, he found the inhabitants living in squalor:

Such law and order as there is administered by warlords. There is little gasoline, so ... everyone goes about on foot. Old peasant women forage for fuel in the woods, because there is no heating oil. Food is scarce, because the men are too busy fighting to tend the fields. In the desolate wastes in front of the bombed-out high rise flats, survivors dig at the ground with hoes. Every man goes armed.[198]

The population increased to about 20,000 as Serb refugees from other parts of Croatia and Bosnia were relocated by RSK authorities. They initially lived without water or electricity, in damaged buildings patched up with plastic sheeting and wooden boards.[199] Residents scavenged the ruins for fragments of glass that they could stick back together to make windows for themselves.[200] The main sources of income were war profiteering and smuggling, though some were able to find jobs in eastern Slavonia's revived oil industry.[201] Reconstruction was greatly delayed by economic sanctions and lack of international aid.[202]

After the Erdut Agreement was signed in 1995, the United Nations Transitional Authority for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium (UNTAES) was established to enable the return of Croatian refugees and to prepare the region for reintegration into Croatia. This UN peacekeeping force provided security during the transition period between 1996 and 1998.[79] It was only in 1999 that Croats began returning to Vukovar in significant numbers, and many of the pre-war inhabitants never returned. By March 2001, the municipality was recorded as having 31,670 inhabitants – less than half the pre-war total – of whom 18,199 (57.46 percent) were Croats and 10,412 (32.88 percent) were Serbs. The community did not recover its mixed character: Croats and Serbs now lived separate social lives. Public facilities such as shops, cafés, restaurants, sports clubs, schools, non-governmental organisations and radio stations were re-established on segregated lines, with separate facilities for each community.[174]

Although the Croatian government sponsored reconstruction efforts in and around Vukovar, the Serb-populated town centre remained in ruins until 2003. Both Croat and Serb residents believed the government had neglected it deliberately, in order to punish the Serb community.[79] Human Rights Watch noted that, of 4,000 homes that had been rebuilt, none of them were inhabited by Serbs.[203] Unemployment was high because of the destruction of the town's major industries, and many of the inhabitants could not sell their houses.[204] Most houses and many of Vukovar's historic buildings had been restored by 2011.[205]

Commemorations and memorials

Signs of the battle are still widely apparent in Vukovar, where many buildings remain visibly scarred by bullets and shrapnel. The town hospital presents an exhibition and reconstruction of the conditions in the building during the battle. At Ovčara, the site of the massacre is marked by a mass grave and exhibition about the atrocity. Local guides, some of whom lived through the battle, offer tourists the opportunity to visit these and other sites on walking and bicycle tours. The riverside water tower was long preserved in its badly damaged state as a war memorial.[206] In 2016, a campaign was launched to restore the water tower to its pre-war state. The reconstructed water tower was opened to the public in October 2020.[207]

Every November, Vukovar's authorities hold four days of festivities to commemorate the town's fall, culminating in a "Procession of Memory" held on 18 November. This represents the expulsion of the town's Croat inhabitants and involves a five-kilometre (3.1 mile) walk from the city's hospital to the Croatian Memorial Cemetery of Homeland War Victims. It is attended by tens of thousands of people from across Croatia.[208] Local Serbs have avoided participating in the Croatian commemorations, often preferring either to leave the town or stay indoors on 18 November. Until 2003, they held a separate, low-key commemoration at the Serbian military cemetery on 17 November.[209] Such commemorations have been held on 18 November since then. The RSK-era term "Liberation Day" has been dropped, but Serbs also avoid using the Croatian terminology, instead calling it simply "18 November".[210] The issue of how to remember the Serb dead has posed particular difficulties. Local Serbs who died fighting alongside the JNA were buried by the Croatian Serb authorities on a plot of land where Croatian houses had once stood.[209] The gravestones were originally topped with a sculptural evocation of the V-shaped Serbian military cap, or šajkača. After Vukovar's reintegration into Croatia, the gravestones were repeatedly vandalised. The Serb community replaced them with more neutral gravestones without overt military connotations.[211] Vukovar Serbs report feeling marginalised and excluded from places associated with Croatian nationalist sentiment, such as war monuments. The Croatian sociologist Kruno Kardov gives the example of a prominent memorial, a large cross made from white stone, where the Vuka flows into the Danube. According to Kardov, Serbs rarely if ever go there, and they feel great stress if they do. A Serb boy spoke of how he wanted to know what was written on the monument but was too frightened to go and read the inscription; one day he got up the courage, ran to the monument, read it and immediately ran back to "safety". As Kardov puts it, Vukovar remains divided by an "invisible boundary line ... inscribed only on the cognitive map of the members of one particular group."[212]

The battle is widely commemorated in Croatia. Almost every town has streets named after Vukovar.[176] In 2009, the lead vessel of the Croatian Navy's two newly launched Helsinki-class missile boats was named after the town.[213] The Croatian Parliament has declared 18 November to be the "Remembrance Day of the Sacrifice of Vukovar in 1991", when "all those who participated in the defence of the city of Vukovar – the symbol of Croatian freedom – are appropriately honoured with dignity."[176]

As a symbol of Croatia's national identity, Vukovar has become a place of pilgrimage for people from across Croatia who seek to evoke feelings of "vicarious insideness", as Kardov describes them, in the suffering endured during the country's war of independence. Some gather in front of the town's main memorial cross on New Year's Eve to pray as the year ends, though such sentiments have attracted criticism from local Croats for not allowing them to "rejoice for even a single night", as one put it.[209] The town has thus become, in Kardov's words, "the embodiment of a pure Croatian identity" and the battle "the foundational myth of the Croatian state". This has led to it becoming as much an "imagined place", a receptacle for Croatian national sentiment and symbolism, as a real place. Kardov concludes that it is questionable whether Vukovar can ever once again be "one place for all its citizens".[214]

In November 2010, Boris Tadić became the first President of Serbia to travel to Vukovar, when he visited the massacre site at Ovčara and expressed his "apology and regret".[215]

Films and books

The battle was portrayed in the Serbian films Dezerter (The Deserter) (1992),[216] Kaži zašto me ostavi (Why Have You Left Me?) (1993)[216] and Vukovar, jedna priča (Vukovar: A Story) (1994);[217] in the Croatian films Vukovar se vraća kući (Vukovar: The Way Home) (1994)[218] and Zapamtite Vukovar (Remember Vukovar) (2008); and in the French film Harrison's Flowers (2000).[219] A 2006 Serbian documentary film about the battle, Vukovar – Final Cut, won the Human Rights Award at the 2006 Sarajevo Film Festival.[220] The battle is also at the centre of Serbian writer Vladimir Arsenijević's 1995 novel U potpalublju (In the Hold).[221]

Notes

- ^ a b Central Intelligence Agency Office of Russian and European Analysis 2000, p. 99

- ^ Woodward 1995, p. 258

- ^ a b c Horton 2003, p. 132

- ^ Notholt 2008, p. 7.28

- ^ Borger, 2011

- ^ a b c Prosecutor v. Milosevic, 23 October 2002

- ^ Prosecutor v. Mrkšić, Radić & Šljivančanin – Judgement, 27 September 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Ivančević 1986, p. 157

- ^ Gow 2003, pp. 159–160

- ^ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, p. 249

- ^ BBC News, 28 January 2003

- ^ Cvitanic 2011, p. 107

- ^ Goldman 1997, p. 310

- ^ a b Boduszyński 2010, pp. 79–80

- ^ a b Bassiouni, Annex IV. 28 December 1994

- ^ Bell 2003, p. 180

- ^ a b O'Shea 2005, p. 11

- ^ a b Bassiouni, Annex III. 28 December 1994

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 49

- ^ Hockenos 2003, pp. 58–59

- ^ Thompson 1999, p. 30

- ^ Stefanovic, 4 May 1991

- ^ a b Thomas & Mikulan 2006, p. 46

- ^ Tanner, 3 May 1991

- ^ Sudetic, 27 August 1991

- ^ Sremac 1999, p. 47

- ^ Tanner, 6 May 1991

- ^ Tanner, 20 May 1991

- ^ Sudetic, 20 May 1991

- ^ Stankovic, 20 June 1991

- ^ Prosecutor v. Mrkšić, Radić & Šljivančanin – Judgement, 27 September 2007, pp. 12–13.

- ^ BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, 9 July 1991

- ^ Jelinić, 31 July 2006

- ^ Stover 2007, p. 146

- ^ Woodward 1995, p. 492

- ^ Lekic, 24 July 1991

- ^ Ramet 2005, pp. 230–231

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 391

- ^ Coward 2009, p. 37

- ^ a b c d Prosecutor v. Mrkšić, Radić & Šljivančanin – Judgement, 27 September 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Central Intelligence Agency Office of Russian and European Analysis 2000, p. 195

- ^ a b Thompson 1992, p. 300

- ^ a b Šebetovsky 2002, p. 11

- ^ a b Marijan 2002, p. 370

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 29

- ^ a b Sikavica 2000, p. 144

- ^ a b Slobodna Dalmacija, 26 September 2009

- ^ Malović & Selnow 2001, p. 132

- ^ a b Gow 2003, p. 239

- ^ a b Butković, 2010

- ^ a b Merrill 1999, p. 119

- ^ Nation 2003, p. 117

- ^ a b c d Tus 2001, p. 54

- ^ a b c d e f Tus 2001, p. 60

- ^ a b c Prosecutor v. Mrkšić, Radić & Šljivančanin – Judgement, 27 September 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Šebetovsky 2002, p. 12

- ^ Marijan 2004, pp. 278–282

- ^ a b c d e f Central Intelligence Agency Office of Russian and European Analysis 2000, p. 100

- ^ Armatta 2010, p. 193

- ^ Kelly 2005, p. 106

- ^ a b c Central Intelligence Agency Office of Russian and European Analysis 2000, p. 92

- ^ Sell 2002, p. 334

- ^ a b c Gibbs 2009, pp. 88–89

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency Office of Russian and European Analysis 2000, pp. 97–98

- ^ Gibbs 2009, p. 252