Hudson River Chains

The term Hudson River Chain may refer to either of two chain booms and two chevaux de frise constructed across the Hudson River at West Point by Colonial forces from 1776 to 1778 during the American Revolutionary War. These served as defenses preventing British naval vessels from sailing upriver, and were, along with the Hudson River itself, overseen by the Highlands Department of the Continental Army.

The first was captured and destroyed by British forces during and in the aftermath of the Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery in October of 1777.

The more significant and successful was the Great Chain, constructed in 1778, and used through war's end in 1782.

Background

Even before the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts both the Americans and British knew that passage on the Hudson River was strategically important to each sides’ war effort. The Americans were desperate to control the river, lest the colonies be divided from one another by its falling into British hands.

The immediate Americans plan was to slow or block ship traffic on the river by attacking British vessels with cannons and mortars from both shores. This anticipated batteries at both existing and planned defensive fortifications.

In late 1776 Henry Wisner, a resident of Goshen, New York and one of New York's representatives to the Continental Congress, along with Gilbert Livingston, sounded the Hudson River and, as part of a Secret Committee of the "Committee of Safety," recommended the placement of chains in strategic locations along the Hudson.[1]

Colonial forces eventually constructed three obstacles across the river: at northern Manhattan between Forts Washington and Lee in 1776; at the lower entrance to the Hudson Highlands, from newly constructed Fort Montgomery on the west bank at Popolopen Creek just north of the modern-day Bear Mountain Bridge to Anthony's Nose on the east bank in 1776–1777; and between West Point and Constitution Island, the Great Chain (1778–1782).

The first two were promptly captured by the British, while the last, the largest and most important of the projects, was reset each spring until the end of the war.

Attention was concentrated on the West Point area because the river narrowed and curved so sharply there that together with shifting winds, tides, and current, ships were slowed in navigating the passage, making them optimal targets.

Fort Lee to Fort Washington chevaux-de-frise (1776)

As part of the barriers erected across the river, the Army constructed chevaux-de-frise, an array of logs sunk underwater, between Fort Washington on the island of Manhattan, and Fort Lee across the river in New Jersey. The logs were intended to pierce and sink any British ships that passed over them. An opening was left for the passage of American ships.

After the British learned of the opening from a local residency they successfully passed through the barrier several times.[2] The British successfully captured both forts in the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776 and Battle of Fort Lee on November 20, putting the defensive barrier in their hands. A change which did not have as dramatic an impact as that may suggest, as the nascent American Navy lacked ships of the size and power of the British, leaving it to resort to small and more maneuverable vessels regardless.

Fort Montgomery Chain (1776–1777)

A chain and boom were stretched across the river from Fort Montgomery on the west bank, at the lower entrance to the Highlands just north of the modern-day Bear Mountain Bridge, to Anthony's Nose on the east bank.

Captain Machin headed the chain effort. In November 1776, a faulty link broke under stress induced by the river tides, highlighting some of the difficulties of trying to chain the Hudson.[3] It was repaired and reset.

After the British captured forts Montgomery and Clinton, a second fortress built opposite it at the mouth of Popolopen's Kill (today's Popolopen Creek) on its south bank, on October 6, 1777, they dismantled the chain [4] and raided upriver as far as Kingston.

Governor Clinton, one of the committee assigned by the New York Convention to devise means of defending the Hudson, was heartened as the British had never attempted to run ships through the chain.[5] He concluded that the basic idea of obstructing the river seemed sound. After Captain Machin recovered from wounds from battle with the British, he began work on the stronger Great Chain at West Point, which was constructed and installed in 1778.

Pollepel Island chevaux-de-frise (1776–1777)

Another chevaux-de-frise was undertaken across the Hudson between Plum Point on the east bank and Pollepel Island north of West Point. The defenses were never fully completed, and its importance was overshadowed by completion of the Great Chain at West Point the following year.

Great Chain (1778–1782)

In the spring of 1778 a heavy chain supported by huge log rafts was stretched across the Hudson from West Point to Constitution Island to impede the movement of British ships north of West Point.

It was constructed over six weeks at the Sterling Iron Works, in Warwick, Orange County, of chain links from Long Pond Iron Works in Ringwood, New Jersey.

The Hudson River's changing tides, strong current, and frequently unfavorable winds created adverse sailing conditions at West Point. Compounding this, the river’s narrow width and sharp "S-Curve" there forced any large ship to tack in order to navigate it. Cannons were placed in forts and artillery batteries on both sides of the river to attack ships when they were slowed to a halt by the Patriot barrier placed there.

When completed the 600 yd (550 m) chain contained iron links two feet in length and weighing 114 pounds (52 kg). The links were carted to New Windsor, New York, where they were put together and floated down the river to West Point on logs late in April. Including swivels, clevises, and anchors, the chain weighed 65 tons. For buoyancy, 40-foot (12 m) logs were cut into 16-foot (4.9 m) sections, waterproofed, and joined by fours into rafts fastened to one-another with 12-foot (3.7 m) timbers. Short sections of chain (10 links, a swivel, and a clevis) were attached across each raft then joined to create a continuous boom of chains and rafts once afloat.

Captain Thomas Machin, the artillery officer and engineer who had installed the chain at Fort Montgomery, directed installation across the river on 30 April 1778. Both ends were anchored to log cribs filled with rocks, the southern at a small cove on the west bank and northern at Constitution Island. The West Point side was protected by the Chain Battery and the Constitution Island side by the Marine Battery.

A system of pulleys, rollers, ropes, and mid-stream anchors were used to adjust the chain's tension to overcome the effects of river current and changing tide. Until 1783 the chain was removed each winter and reinstalled each spring to avoid destruction by ice. A second log "boom" (resembling a ladder in construction) spanned the river about 100 yards (91 m) downstream (south of the chain) to absorb the impact of any ship attempting to breach the barrier.

The British never attempted to run the chain, in spite of then still a Colonial general and soon to be traitor Benedict Arnold claiming in correspondence with them that "a well-loaded ship could break the chain."[6] Polish engineer and Patriot volunteer Thaddeus Kościuszko contributed to the system of fortifications at West Point.[7]: 52–70

Memorials

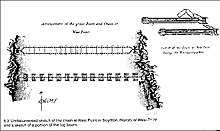

After the Revolution part of the chain was saved for posterity and the rest relegated to the West Point Foundry furnaces near Cold Spring, New York, to be melted down for other uses.[8] A saved portion was first displayed at the West Point ordnance compound, along with a captured mortar, as shown in the 1905 drawing.[9]

More recently, thirteen links worth have been displayed at Trophy Point, each representing one of Colonies turned founding States of the USA. Also included are a swivel and clevis. The exhibit is maintained and preserved by the West Point Museum.[10] A section of boom recovered from the river in 1855 is displayed at Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site in Newburgh, New York.

Two links of the original chain are also at Raynham Hall in Oyster Bay, New York, the home of Robert Townsend, a cousin of iron works owner Peter Townsend, and (as "Culper Jr") a member of George Washington’s Culper spy ring.

Bilking the gullible, John C. Abbey,[who?] and later Pollepel Island owner Francis Bannerman, sold counterfeit chain links to collectors and museums.[11]

Bibliography

- "Hudson River Chain", Harper's Encyclopedia of United States History, Vol. IV, p. 447, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1905.

- Information plaques at Trophy Point at West Point, New York.

- "West Point Fortifications", Scribd

- U.S. Military Academy Department of History, West Point Fortifications Staff Ride Notecards, second edition (1998)

References

- ^ Letter from Henry Wisner and Gilbert Livingston to New-York Committee of Safety: Soundings of Hudson river in the Highlands American Archives Series 5, Volume 3, Page 0812 November 22, 1776. http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.27283 Archived 2014-12-04 at the Wayback Machine Accessed February 19, 2015.

- ^ Diamant, Chaining The Hudson, 1989

- ^ Diamant, Chaining the Hudson, 1989, p 105

- ^ West Point Fortifications Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Diamant, Chaining the Hudson, p. 122

- ^ "The Great Chain" Archived 2008-09-07 at the Wayback Machine, University of North Carolina

- ^ Storozynski, A., 2009, The Peasant Prince, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 9780312388027

- ^ The Chaining of the Hudson

- ^ West Point Museum e-mail correspondence

- ^ "USMA: West Point Museum". Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ Diamant, The Chaining of the Hudson -- And Profiteering on History, Hudson River[clarification needed]

External links

- Merle Sheffield, The Chain and Boom, Hudson River Valley, official website

- West Point Fortifications

- The Great Chain

- Chaining of the Hudson in 1778

- The Great Chain

- Chaining The Hudson

- George Washington's letter about the strategic importance of the Hudson[permanent dead link]

- Contract for the forging of The Great Chain[permanent dead link]

- New York Times Article about The Chain February 17, 1895

- Chain Salvaging Blurb

- "Revolutionary West Point: 'The Key to the Continent'",