Viking program

Artist impression of a Viking orbiter releasing a lander descent capsule | |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Martin Marietta |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| Applications | Mars orbiter/lander |

| Specifications | |

| Launch mass | 3,527 kilograms (7,776 lb) |

| Power | Orbiters: 620 watts (solar array) Lander: 70 watts (two RTG units) |

| Regime | Areocentric |

| Design life | Orbiters: 4 years at Mars Landers: 4–6 years at Mars |

| Production | |

| Status | Retired |

| Built | 2 |

| Launched | 2 |

| Retired | Viking 1 orbiter August 17, 1980[1] Viking 1 lander July 20, 1976[1] (landing) to November 13, 1982[1] Viking 2 orbiter July 25, 1978[1] Viking 2 lander September 3, 1976[1] (landing) to April 11, 1980[1] |

| Maiden launch | Viking 1 August 20, 1975[1][2] |

| Last launch | Viking 2 September 9, 1975[1][3] |

The Viking program consisted of a pair of identical American space probes, Viking 1 and Viking 2, which landed on Mars in 1976.[1] Each spacecraft was composed of two main parts: an orbiter designed to photograph the surface of Mars from orbit, and a lander designed to study the planet from the surface. The orbiters also served as communication relays for the landers once they touched down.

The Viking program grew from NASA's earlier, even more ambitious, Voyager Mars program, which was not related to the successful Voyager deep space probes of the late 1970s. Viking 1 was launched on August 20, 1975, and the second craft, Viking 2, was launched on September 9, 1975, both riding atop Titan IIIE rockets with Centaur upper stages. Viking 1 entered Mars orbit on June 19, 1976, with Viking 2 following on August 7.

After orbiting Mars for more than a month and returning images used for landing site selection, the orbiters and landers detached; the landers then entered the Martian atmosphere and soft-landed at the sites that had been chosen. The Viking 1 lander touched down on the surface of Mars on July 20, 1976, more than two-weeks before Viking 2's arrival in orbit. Viking 2 then successfully soft-landed on September 3. The orbiters continued imaging and performing other scientific operations from orbit while the landers deployed instruments on the surface.

The project cost was roughly $1 billion at the time of launch,[4][5] equivalent to about 6 billion USD in 2023 dollars.[6] The mission was considered successful and is credited with helping to form most of the body of knowledge about Mars through the late 1990s and early 2000s.[7][8]

Science objectives

- Obtain high-resolution images of the Martian surface

- Characterize the structure and composition of the atmosphere and surface

- Search for evidence of life on Mars

Viking orbiters

The primary objectives of the two Viking orbiters were to transport the landers to Mars, perform reconnaissance to locate and certify landing sites, act as communications relays for the landers, and to perform their own scientific investigations. Each orbiter, based on the earlier Mariner 9 spacecraft, was an octagon approximately 2.5 m across. The fully fueled orbiter-lander pair had a mass of 3527 kg. After separation and landing, the lander had a mass of about 600 kg and the orbiter 900 kg. The total launch mass was 2328 kg, of which 1445 kg were propellant and attitude control gas. The eight faces of the ring-like structure were 0.4572 m high and were alternately 1.397 and 0.508 m wide. The overall height was 3.29 m from the lander attachment points on the bottom to the launch vehicle attachment points on top. There were 16 modular compartments, 3 on each of the 4 long faces and one on each short face. Four solar panel wings extended from the axis of the orbiter, the distance from tip to tip of two oppositely extended solar panels was 9.75 m.

Propulsion

The main propulsion unit was mounted above the orbiter bus. Propulsion was furnished by a bipropellant (monomethylhydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide) liquid-fueled rocket engine which could be gimballed up to 9 degrees. The engine was capable of 1,323 N (297 lbf) thrust, providing a change in velocity of 1480 m/s. Attitude control was achieved by 12 small compressed-nitrogen jets.

Navigation and communication

An acquisition Sun sensor, a cruise Sun sensor, a Canopus star tracker and an inertial reference unit consisting of six gyroscopes allowed three-axis stabilization. Two accelerometers were also on board. Communications were accomplished through a 20 W S-band (2.3 GHz) transmitter and two 20 W TWTAs. An X band (8.4 GHz) downlink was also added specifically for radio science and to conduct communications experiments. Uplink was via S band (2.1 GHz). A two-axis steerable parabolic dish antenna with a diameter of approximately 1.5 m was attached at one edge of the orbiter base, and a fixed low-gain antenna extended from the top of the bus. Two tape recorders were each capable of storing 1280 megabits. A 381-MHz relay radio was also available.

Power

The power to the two orbiter craft was provided by eight 1.57 × 1.23 m solar panels, two on each wing. The solar panels comprised a total of 34,800 solar cells and produced 620 W of power at Mars. Power was also stored in two nickel-cadmium 30-A·h batteries.

The combined area of the four panels was 15 square meters (160 square feet), and they provided both regulated and unregulated direct current power; unregulated power was provided to the radio transmitter and the lander.

Two 30-amp-hour, nickel-cadmium, rechargeable batteries provided power when the spacecraft was not facing the Sun, during launch, while performing correction maneuvers and also during Mars occultation.[9]

Main findings

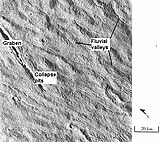

By discovering many geological forms that are typically formed from large amounts of water, the images from the orbiters caused a revolution in our ideas about water on Mars. Huge river valleys were found in many areas. They showed that floods of water broke through dams, carved deep valleys, eroded grooves into bedrock, and travelled thousands of kilometers. Large areas in the southern hemisphere contained branched stream networks, suggesting that rain once fell. The flanks of some volcanoes are believed to have been exposed to rainfall because they resemble those caused on Hawaiian volcanoes. Many craters look as if the impactor fell into mud. When they were formed, ice in the soil may have melted, turned the ground into mud, then flowed across the surface. Normally, material from an impact goes up, then down. It does not flow across the surface, going around obstacles, as it does on some Martian craters.[10][11][12] Regions, called "Chaotic Terrain," seemed to have quickly lost great volumes of water, causing large channels to be formed. The amount of water involved was estimated to ten thousand times the flow of the Mississippi River.[13] Underground volcanism may have melted frozen ice; the water then flowed away and the ground collapsed to leave chaotic terrain.

-

Streamlined islands show that large floods occurred on Mars.

(Lunae Palus quadrangle) -

Scour patterns were produced by flowing water. Dromore crater is at bottom.

(Lunae Palus quadrangle) -

Arandas crater may be on top of large quantities of water ice, which melted when the impact occurred, producing a mud-like ejecta.

(Mare Acidalium quadrangle) -

Branched channels in Thaumasia quadrangle provide possible evidence of past rain on Mars.

-

These branched channels provide possible evidence of past rain on Mars. (Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle)

Viking landers

Each lander comprised a six-sided aluminium base with alternate 1.09 and 0.56 m (3 ft 7 in and 1 ft 10 in) long sides, supported on three extended legs attached to the shorter sides. The leg footpads formed the vertices of an equilateral triangle with 2.21 m (7 ft 3 in) sides when viewed from above, with the long sides of the base forming a straight line with the two adjoining footpads. Instrumentation was attached inside and on top of the base, elevated above the surface by the extended legs.[14]

Each lander was enclosed in an aeroshell heat shield designed to slow the lander down during the entry phase. To prevent contamination of Mars by Earth organisms, each lander, upon assembly and enclosure within the aeroshell, was enclosed in a pressurized "bioshield" and then sterilized at a temperature of 111 °C (232 °F) for 40 hours. For thermal reasons, the cap of the bioshield was jettisoned after the Centaur upper stage powered the Viking orbiter/lander combination out of Earth orbit.[15]

Entry, Descent and Landing (EDL)

Each lander arrived at Mars attached to the orbiter. The assembly orbited Mars many times before the lander was released and separated from the orbiter for descent to the surface. Descent comprised four distinct phases, starting with a deorbit burn. The lander then experienced atmospheric entry with peak heating occurring a few seconds after the start of frictional heating with the Martian atmosphere. At an altitude of about 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) and traveling at a velocity of 900 kilometers per hour (600 mph), the parachute deployed, the aeroshell released and the lander's legs unfolded. At an altitude of about 1.5 kilometers (5,000 feet), the lander activated its three retro-engines and was released from the parachute. The lander then immediately used retrorockets to slow and control its descent, with a soft landing on the surface of Mars.[16]

At landing (after using rocket propellant) the landers had a mass of about 600 kg.

Propulsion

Propulsion for deorbit was provided by the monopropellant hydrazine (N2H4), through a rocket with 12 nozzles arranged in four clusters of three that provided 32 newtons (7.2 lbf) thrust, translating to a change in velocity of 180 m/s (590 ft/s). These nozzles also acted as the control thrusters for translation and rotation of the lander.

Terminal descent (after use of a parachute) and landing utilized three (one affixed on each long side of the base, separated by 120 degrees) monopropellant hydrazine engines. The engines had 18 nozzles to disperse the exhaust and minimize effects on the ground, and were throttleable from 276 to 2,667 newtons (62 to 600 lbf). The hydrazine was purified in order to prevent contamination of the Martian surface with Earth microbes. The lander carried 85 kg (187 lb) of propellant at launch, contained in two spherical titanium tanks mounted on opposite sides of the lander beneath the RTG windscreens, giving a total launch mass of 657 kg (1,448 lb). Control was achieved through the use of an inertial reference unit, four gyros, a radar altimeter, a terminal descent and landing radar, and the control thrusters.

Power

Power was provided by two radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) units containing plutonium-238 affixed to opposite sides of the lander base and covered by wind screens. Each Viking RTG was 28 cm (11 in) tall, 58 cm (23 in) in diameter, had a mass of 13.6 kg (30 lb) and provided 30 watts continuous power at 4.4 volts. Four wet cell sealed nickel-cadmium 8 Ah (28,800 coulombs), 28 volt rechargeable batteries were also on board to handle peak power loads.

Payload

Communications were accomplished through a 20-watt S-band transmitter using two traveling-wave tubes. A two-axis steerable high-gain parabolic antenna was mounted on a boom near one edge of the lander base. An omnidirectional low-gain S-band antenna also extended from the base. Both these antennae allowed for communication directly with the Earth, permitting Viking 1 to continue to work long after both orbiters had failed. A UHF (381 MHz) antenna provided a one-way relay to the orbiter using a 30 watt relay radio. Data storage was on a 40-Mbit tape recorder, and the lander computer had a 6000-word memory for command instructions.

The lander carried instruments to achieve the primary scientific objectives of the lander mission: to study the biology, chemical composition (organic and inorganic), meteorology, seismology, magnetic properties, appearance, and physical properties of the Martian surface and atmosphere. Two 360-degree cylindrical scan cameras were mounted near one long side of the base. From the center of this side extended the sampler arm, with a collector head, temperature sensor, and magnet on the end. A meteorology boom, holding temperature, wind direction, and wind velocity sensors extended out and up from the top of one of the lander legs. A seismometer, magnet and camera test targets, and magnifying mirror are mounted opposite the cameras, near the high-gain antenna. An interior environmentally controlled compartment held the biology experiment and the gas chromatograph mass spectrometer. The X-ray fluorescence spectrometer was also mounted within the structure. A pressure sensor was attached under the lander body. The scientific payload had a total mass of approximately 91 kg (201 lb).

Biological experiments

The Viking landers conducted biological experiments designed to detect life in the Martian soil (if it existed) with experiments designed by three separate teams, under the direction of chief scientist Gerald Soffen of NASA. One experiment turned positive for the detection of metabolism (current life), but based on the results of the other two experiments that failed to reveal any organic molecules in the soil, most scientists became convinced that the positive results were likely caused by non-biological chemical reactions from highly oxidizing soil conditions.[17]

Although there was a pronouncement by NASA during the mission saying that the Viking lander results did not demonstrate conclusive biosignatures in soils at the two landing sites, the test results and their limitations are still under assessment. The validity of the positive 'Labeled Release' (LR) results hinged entirely on the absence of an oxidative agent in the Martian soil, but one was later discovered by the Phoenix lander in the form of perchlorate salts.[18][19] It has been proposed that organic compounds could have been present in the soil analyzed by both Viking 1 and Viking 2, but remained unnoticed due to the presence of perchlorate, as detected by Phoenix in 2008.[20] Researchers found that perchlorate will destroy organics when heated and will produce chloromethane and dichloromethane, the identical chlorine compounds discovered by both Viking landers when they performed the same tests on Mars.[21]

The question of microbial life on Mars remains unresolved. Nonetheless, on April 12, 2012, an international team of scientists reported studies, based on mathematical speculation through complexity analysis of the Labeled Release experiments of the 1976 Viking Mission, that may suggest the detection of "extant microbial life on Mars."[22][23] In addition, new findings from re-examination of the Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) results were published in 2018.[24]

Camera/imaging system

The leader of the imaging team was Thomas A. Mutch, a geologist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. The camera uses a movable mirror to illuminate 12 photo diodes. Each of the 12 silicon diodes are designed to be sensitive to different frequences of light. Several diodes are placed to focus accurately at distances between six and 43 feet away from the lander.

The cameras scanned at a rate of five vertical scan lines per second, each composed of 512 pixels. The 300 degree panorama images were composed of 9150 lines. The cameras’ scan was slow enough that in a crew shot taken during development of the imaging system several members show up several times in the shot as they moved themselves as the camera scanned.[25][26]

Control systems

The Viking landers used a Guidance, Control and Sequencing Computer (GCSC) consisting of two Honeywell HDC 402 24-bit computers with 18K of plated-wire memory, while the Viking orbiters used a Command Computer Subsystem (CCS) using two custom-designed 18-bit serial processors.[27][28][29]

Financial cost of the Viking program

The two orbiters cost US$217 million (at the time), which is about 1 billion USD in year-2023 dollars.[30][31] The most expensive single part of the program was the lander's life-detection unit, which cost about 60 million then or 400 million USD in 2023 year-dollars.[30][31] Development of the Viking lander design cost US$357 million.[30] This was decades before NASA's "faster, better, cheaper" approach, and Viking needed to pioneer unprecedented technologies under national pressure brought on by the Cold War and the aftermath of the Space Race, all under the prospect of possibly discovering extraterrestrial life for the first time.[30] The experiments had to adhere to a special 1971 directive that mandated that no single failure shall stop the return of more than one experiment—a difficult and expensive task for a device with over 40,000 parts.[30]

The Viking camera system cost US$27.3 million to develop, or about 200 million in 2023 year-dollars.[30][31] When the Imaging system design was completed, it was difficult to find anyone who could manufacture its advanced design.[30] The program managers were later praised for fending off pressure to go with a simpler, less advanced imaging system, especially when the views rolled in.[30] The program did however save some money by cutting out a third lander and reducing the number of experiments on the lander.[30]

Overall NASA says that US$1 billion in 1970s dollars was spent on the program,[4][5] which when inflation-adjusted to 2023 dollars is about 6 billion USD.[31]

Mission end

The craft all eventually failed, one by one, as follows:[1]

| Craft | Arrival date | Shut-off date | Operational lifetime | Cause of failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viking 2 orbiter | August 7, 1976 | July 25, 1978 | 1 year, 11 months, 18 days | Shut down after fuel leak in propulsion system. |

| Viking 2 lander | September 3, 1976 | April 11, 1980 | 3 years, 7 months, 8 days | Shut down after battery failure. |

| Viking 1 orbiter | June 19, 1976 | August 17, 1980 | 4 years, 1-month, 19 days | Shut down after depletion of attitude control fuel. |

| Viking 1 lander | July 20, 1976 | November 13, 1982 | 6 years, 3 months, 22 days | Shut down after human error during software update caused the lander's antenna to go down, terminating power and communication. |

The Viking program ended on May 21, 1983. To prevent an imminent impact with Mars the orbit of Viking 1 orbiter was raised on August 7, 1980, before it was shut down 10 days later. Impact and potential contamination on the planet's surface is possible from 2019 onwards.[4]

The Viking 1 lander was found to be about 6 kilometers from its planned landing site by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in December 2006. [32]

Message artifact

(See also List of extraterrestrial memorials and Category:Message artifacts)

Each Viking lander carried a tiny dot of microfilm containing the names of several thousand people who had worked on the mission.[33] Several earlier space probes had carried message artifacts, such as the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record. Later probes also carried memorials or lists of names, such as the Perseverance rover which recognizes the almost 11 million people who signed up to include their names on the mission.

Viking lander locations

See also

- Composition of Mars – Branch of the geology of Mars

- Curiosity rover

- ExoMars – Astrobiology programme

- Exploration of Mars

- Life on Mars – Scientific assessments on the microbial habitability of Mars

- List of missions to Mars

- List of rocks on Mars – Alphabetical list of named rocks and meteorites found on Mars

- Mariner 9 – First spacecraft to enter orbit around Mars (1971–1972)

- Mars Science Laboratory – Robotic mission that deployed the Curiosity rover to Mars in 2012

- Mars Pathfinder – Mission including first robotic rover to operate on Mars (1997)

- Norman L. Crabill – NASA engineer (1926–2024)

- Opportunity rover

- Robotic spacecraft – Spacecraft without people on board

- Space exploration – Exploration of space, planets, and moons

- Spirit rover

- U.S. Space Exploration History on U.S. Stamps – Overview of ventures beyond Earth as depicted for ease of American postage

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Williams, David R. Dr. (December 18, 2006). "Viking Mission to Mars". NASA. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Nelson, Jon. "Viking 1". NASA. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Nelson, Jon. "Viking 2". NASA. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Viking 1 Orbiter spacecraft details". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. NASA. March 20, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "Viking 1: First U.S. Lander on Mars". Space.com. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ "The Viking Program". The Center for Planetary Science. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Viking Lander". California Science Center. July 3, 2014. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Sitemap – NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Hugh H. Kieffer (1992). Mars. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1257-7. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Raeburn, P. 1998. Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet Mars. National Geographic Society. Washington D.C.

- ^ Moore, P. et al. 1990. The Atlas of the Solar System. Mitchell Beazley Publishers NY, NY.

- ^ Morton, O. 2002. Mapping Mars. Picador, NY, NY

- ^ Hearst Magazines (June 1976). "Amazing Search for Life On Mars". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. pp. 61–63.

- ^ Soffen, G. A., and C. W. Snyder, First Viking mission to Mars, Science, 193, 759–766, August 1976.

- ^ "Viking". astro.if.ufrgs.br.

- ^ BEEGLE, LUTHER W.; et al. (August 2007). "A Concept for NASA's Mars 2016 Astrobiology Field Laboratory". Astrobiology. 7 (4): 545–577. Bibcode:2007AsBio...7..545B. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0153. PMID 17723090.

- ^ Johnson, John (August 6, 2008). "Perchlorate found in Martian soil". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Martian Life Or Not? NASA's Phoenix Team Analyzes Results". Science Daily. August 6, 2008.

- ^ Navarro–Gonzáles, Rafael; Edgar Vargas; José de la Rosa; Alejandro C. Raga; Christopher P. McKay (December 15, 2010). "Reanalysis of the Viking results suggests perchlorate and organics at midlatitudes on Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. Vol. 115, no. E12010. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ^ Than, Ker (April 15, 2012). "Life on Mars Found by NASA's Viking Mission". National Geographic. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Bianciardi, Giorgio; Miller, Joseph D.; Straat, Patricia Ann; Levin, Gilbert V. (March 2012). "Complexity Analysis of the Viking Labeled Release Experiments". IJASS. 13 (1): 14–26. Bibcode:2012IJASS..13...14B. doi:10.5139/IJASS.2012.13.1.14.

- ^ Klotz, Irene (April 12, 2012). "Mars Viking Robots 'Found Life'". DiscoveryNews. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ Guzman, Melissa; McKay, Christopher P.; Quinn, Richard C.; Szopa, Cyril; Davila, Alfonso F.; Navarro‐González, Rafael; Freissinet, Caroline (2018). "Identification of Chlorobenzene in the Viking Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer Data Sets: Reanalysis of Viking Mission Data Consistent With Aromatic Organic Compounds on Mars" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 123 (7): 1674–1683. Bibcode:2018JGRE..123.1674G. doi:10.1029/2018JE005544. ISSN 2169-9100.

- ^ The Viking Lander Imaging Team (1978). "Chapter 8: Cameras Without Pictures". The Martian Landscape. NASA. p. 22.

- ^ McElheny, Victor K. (July 21, 1976). "Viking Cameras Light in Weight, Use Little Power, Work Slowly". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ Tomayko, James (April 1987). "Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience". NASA. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ Holmberg, Neil A.; Robert P. Faust; H. Milton Holt (November 1980). "NASA Reference Publication 1027: Viking '75 spacecraft design and test summary. Volume 1 – Lander design" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ Holmberg, Neil A.; Robert P. Faust; H. Milton Holt (November 1980). "NASA Reference Publication 1027: Viking '75 spacecraft design and test summary. Volume 2 – Orbiter design" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McCurdy, Howard E. (2001). Faster, Better, Cheaper: Low-Cost Innovation in the U.S. Space Program. JHU Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8018-6720-0.

- ^ a b c d As the Viking program was a government expense, the inflation index of the United States Nominal Gross Domestic Product per capita is used for the inflation-adjusting calculation.

- ^ Chandler, David (December 5, 2006). "Probe's powerful camera spots Vikings on Mars". New Scientist. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ "Visions of Mars: Then and Now". The Planetary Society.

Further reading

|

External links

- NASA Mars Viking Mission

- Viking Mission to Mars (NASA SP-334) Archived August 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Solar Views Project Viking Fact Sheet

- Viking Mission to Mars Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Video

- A diagram of the Viking and its flight profile

- Article at Smithsonian Air and Space Website

- The Viking Mars Missions Education & Preservation Project (VMMEPP)

- VMMEPP Online exhibit