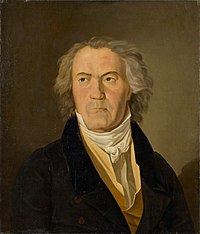

Ludwig van Beethoven

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

Ludwig van Beethoven (IPA: [lʊtvɪç va:n be:tovən], baptized December 17, 1770[1] – March 26, 1827) was a German composer. He is generally regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of music, and was the predominant figure in the transitional period between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western classical music. His reputation and genius have inspired — and in many cases intimidated — ensuing generations of composers, musicians, and audiences. While primarily known today as a composer, he was also a celebrated pianist and conductor, and an accomplished violinist.

Born in Bonn, Germany, he moved to Vienna, Austria, in his early twenties, and settled there, studying with Joseph Haydn and quickly gaining a reputation as a virtuoso pianist. In his late twenties he began to lose his hearing gradually, and yet he continued to produce notable masterpieces throughout his life, even when his deafness was almost total. Beethoven was one of the first composers who worked as a freelance — arranging subscription concerts, selling his compositions to publishers, and gaining financial support from a number of wealthy patrons — rather than being permanently employed by the church or by an aristocratic court.

Life

Beethoven was born at Bonngasse 515 (today Bonngasse 20) in Bonn, Germany to Johann van Beethoven (1740–1792) of Flemish origin and Magdalena Keverich van Beethoven (1744–1787) of Slavic ancestry. Beethoven was baptized on December 17, but his family and later his teacher Johann Albrechtsberger celebrated his birthday on December 16.

Beethoven's first music teacher was his father, a musician in the Electoral court at Bonn, who was apparently a harsh and unpredictable instructor. Johann would often come home from a bar in the middle of the night and pull young Ludwig out of bed to play for him and his friend. Beethoven's talent was recognized at a very early age. His first important teacher was Christian Gottlob Neefe. In 1787 young Beethoven traveled to Vienna for the first time, where he may have met and played for Mozart. He was forced to return home because his mother was dying of tuberculosis. Beethoven's mother died when he was 16, shortly followed by his sister, and for several years he was responsible for raising his two younger brothers because of his father's worsening alcoholism.

Beethoven moved to Vienna in 1792, where he studied for a time with Joseph Haydn, though he had wanted to study with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who had died the previous year. He received additional instruction from Johann Georg Albrechtsberger (Vienna's preeminent counterpoint instructor), and Antonio Salieri. Beethoven immediately established a reputation as a piano virtuoso. His first works with opus numbers, a set of three piano trios, appeared in 1795. He settled into the career pattern he would follow for the remainder of his life: rather than working for the church or a noble court (as most composers before him had done), he supported himself through a combination of annual stipends or single gifts from members of the aristocracy, income from subscription concerts, concerts, and lessons, and proceeds from sales of his works.

Loss of hearing

Around 1796, Beethoven began to lose his hearing.[2] He suffered a severe form of tinnitus, a "roar" in his ears that made it hard for him to perceive and appreciate music; he would also avoid conversation. The cause of Beethoven's deafness is unknown, but it has variously been attributed to syphilis, beatings from his father, lead poisoning, typhus, and even his habit of immersing his head in cold water to stay awake. The oldest explanation, from the autopsy of the time, is that he had a "distended inner ear" which developed lesions over time.

Russell Martin has shown from analysis done on a sample of Beethoven's hair that there were alarmingly high levels of lead in Beethoven's system. High concentrations of lead can lead to bizarre and erratic behaviour, including rages. Another symptom of lead poisoning is deafness. In Beethoven's time, lead was used widely without an understanding of the damage it could cause. It was used in sweetening wine, in finishes on porcelain dishes, and even in medicines. The investigation of this link was detailed in the book Beethoven's Hair: An Extraordinary Historical Odyssey and a Scientific Mystery Solved. However, while the likelihood of lead poisoning is very high, the deafness associated with it seldom takes the form that Beethoven exhibited.

In 1802, he became depressed, and considered committing suicide. He left Vienna for a time for the small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt, where he wrote his Heiligenstadt Testament. He resolved to continue living for and through his art. Over time, his hearing loss became profound: there is a well-attested story that, at the end of the premiere of his Ninth Symphony, he had to be turned around to see the tumultuous applause of the audience; hearing nothing, he began to weep. Beethoven's hearing loss did not affect his ability to compose music, but it made concerts — lucrative sources of income — increasingly difficult.

As a result of Beethoven's hearing loss, a unique historical record has been preserved: he kept conversation books discussing music and other issues, and giving an insight into his thought. Even today, the conversation books form the basis for investigation into how he felt his music should be performed, and his relationship to art — which he took very seriously.

Social difficulties

Beethoven's personal life was troubled. His encroaching deafness led him to think about suicide (documented in his Heiligenstadt Testament), as mentioned above. He was attracted to "unattainable" women (married or aristocratic); he never married. His only love affair with an identified woman began in 1805 with Josephine von Brunswick; most scholars think it ended by 1807 because she could not marry a commoner without losing custody of her children. In 1812 he wrote a long love letter to a woman only identified therein as the "Immortal Beloved". Several candidates have been suggested, but nobody knows for certain who she was. Some scholars believe his period of low productivity from about 1812 to 1816 was caused by depression resulting from Beethoven's realization that he would never marry.

Beethoven quarreled, often bitterly, with his relatives and others (including a painful and public custody battle over his nephew Karl). He frequently treated other people badly. He changed addresses often, and had strange personal habits, such as wearing dirty clothing even as he washed compulsively.[citation needed] Nonetheless, he had a close and devoted circle of friends all his life.

Many listeners perceive echoes of Beethoven's life in his music, which often depicts struggle followed by triumph. This description is often applied to Beethoven's creation of masterpieces in the face of his severe personal difficulties.

Personal beliefs and their musical influence

Beethoven was attracted to the ideals of the Enlightenment and by the growing Romanticism in Europe. He initially dedicated his third symphony, the Eroica (Italian for "heroic"), to Napoleon in the belief that the general would sustain the democratic and republican ideals of the French Revolution, but in 1804, when Napoleon's imperial ambitions became clear, he crossed out Napoleon's name on the title page. He renamed the symphony "Sinfonia Eroica, composta per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grand Uomo" ("Heroic Symphony, composed to celebrate the memory of a great man"). The fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony features an elaborate choral setting of Schiller's Ode An die Freude ("Ode To Joy"), an optimistic hymn championing the brotherhood of humanity. Since 1972, an orchestral version of the fourth movement has been the official anthem of the European Union.

Scholars disagree on Beethoven's religious beliefs and the role they played in his work. For discussion, see Ludwig van Beethoven's religious beliefs. It has been asserted, but not proven, that Beethoven was a Freemason.[3]

His music

- Main article: Beethoven's musical style and innovations

Beethoven was one of the greatest masters of musical construction, sometimes sketching the architecture of a movement before he had the subject-matter more than dimly in his mind. He was the first composer systematically and consistently to use interlocking thematic devices, or "germ-motives", to achieve inter-movement unity in long compositions. Equally remarkable was his use of "source-motives", which recurred in many different compositions and lent some unity to his life's work. He made innovations in almost every form of music he touched. For example, he diversified even such a well-crystallized form as the rondo, making it more elastic and spacious, which brought it closer to sonata form.

Beethoven's most recognized, concrete, and original contributions can be grouped into four types:

1) The sonata-form movement of titanic and elemental struggle (string quartets Op. 18 No. 4 and Op. 95; the Eroica, 5th, and 9th ("Choral") Symphonies; and the piano sonatas Pathetique, Appassionata, and C minor Op. 111).

2) The scherzo of tumultuous, headlong humor and intoxicating energy (string quartets Op. 18 No. 6, Op. 59 No. 1, Op. 130, and Op. 131; the 7th and 9th Symphonies; the piano sonata in G Op. 14; the violin sonata in F Op. 24; and the cello sonata in A Op. 69).

3) The ethereal slow movement of mystic glorification (9th symphony; string quartets Op. 59 No. 2, Op. 127, Op. 132, and Op. 135; the piano sonatas Op. 106 called the Hammerklavier, E Major Op. 109, and C minor Op. 111; the 5th piano concerto called the Emperor; the Benedictus of the Missa Solemnis; and the "Archduke" piano trio Op. 97).

4) The expansion and weight given to the 'symphonic' finale (the 3rd, 5th, and 9th symphonies; the "Waldstein" and "Hammerklavier" piano sonatas; and the Grosse Fuge - the original finale from the string quartet in B-flat, Op. 130).

Beethoven composed in a great variety of genres, including symphonies, concerti, piano sonatas, other sonatas (including for violin), string quartets and other chamber music, masses, an opera, lieder, and various other genres. He is viewed as one of the most important transitional figures between the Classical and Romantic eras of musical history.

As far as musical form is concerned, Beethoven worked from the principles of sonata form and motivic development that he had inherited from Haydn and Mozart, but greatly extended them, writing longer and more ambitious movements.

The three periods

Beethoven's career as a composer is usually divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods.

In the Early period, he is seen as emulating his great predecessors Haydn and Mozart, while concurrently exploring new directions and gradually expanding the scope and ambition of his work. Some important pieces from the Early period are the first and second symphonies, the first six string quartets, the first three piano concertos, and the first twenty piano sonatas, including the famous Pathétique and Moonlight.

The Middle period began shortly after Beethoven's personal crisis centering around his encroaching deafness. The period is noted for large-scale works expressing heroism and struggle; these include many of the most famous works of classical music. Middle-period works include six symphonies (Nos. 3–8), the fourth and fifth piano concertos, the triple concerto and violin concerto, five string quartets (Nos. 7–11), the next seven piano sonatas including the Waldstein, and Appassionata, and his only opera, Fidelio.

Beethoven's Late period began around 1816. The Late-period works are greatly admired for their characteristic intellectual depth, their intense and highly personal expression, and experimentation with forms (for example, the Quartet in C Sharp Minor has seven linked movements, and his Ninth Symphony adds choral forces to the orchestra in the last movement). Works of this period also includes the Missa Solemnis, the last five string quartets, and the last five piano sonatas.

Beethoven in popular culture

The composer appears frequently in film and other works of popular culture. For a list, see Ludwig van Beethoven in popular culture.

See also

- List of works by Beethoven, including links to all of the works with their own article

- Category: Compositions by Ludwig van Beethoven

- Cultural depictions of Ludwig van Beethoven

- Beethoven and his contemporaries

- List of historical sites associated with Ludwig van Beethoven

- Three-key exposition

- Beethoven Gesamtausgabe

Media

Piano solo Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item

Orchestral Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item

Chamber Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item

Other Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item

- Problems playing the files? See media help.

Notes

- ^ Beethoven was baptised on 17 December 1770. For many years he believed he had been born in 1772, because of his father's efforts to pass him off as a child prodigy similar to Mozart — the father tried to make him seem younger than he was. Children of that era were usually baptised the day after their birth, but there is no documentary evidence that this occurred in Beethoven's case. It is known that his family and his teacher Johann Albrechtsberger celebrated his birthday on 16 December. While the known facts support the probability that 16 December 1770 was Beethoven's date of birth, this cannot be stated with certainty.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ludwig van Beethoven - Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon

References

- Albrecht, Theodor, and Elaine Schwensen, "More Than Just Peanuts: Evidence for December 16 as Beethoven's birthday." The Beethoven Newsletter 3 (1988): 49, 60-63.

- Clive, Peter. Beethoven and His World: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-816672-9.

- Davies, Peter. The Character of a Genius: Beethoven in Perspective. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002. ISBN 0-313-31913-8.

- Oscar, Thompson. The International Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians. London: J.M.Dent & Sons LTD, 1975. ISBN 0-460-04235-1.

- _____. Beethoven in Person: His Deafness, Illnesses, and Death. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2001. ISBN 0-313-31587-6.

- DeNora, Tia. "Beethoven and the Construction of Genius: Musical Politics in Vienna, 1792-1803." Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1995. ISBN 0-520-21158-8.

- Geck, Martin. Beethoven. Translated by Anthea Bell. London: Haus, 2003. ISBN 1-904341-03-9 (h), ISBN 1-904341-00-4 (p).

- Hatten, Robert S. Musical Meaning in Beethoven. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 372. ISBN 0-253-32742-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|tear=ignored (help) - Kropfinger, Klaus. Beethoven. Verlage Bärenreiter/Metzler, 2001. ISBN 3-7618-1621-9.

- Meredith, William. "The History of Beethoven's Skull Fragments." The Beethoven Journal 20 (2005): 3-46.

- Morris, Edmund. Beethoven: The Universal Composer. New York: Atlas Books / HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 0-06-075974-7.

- Solomon, Maynard. Beethoven, 2nd revised edition. New York: Schirmer Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8256-7268-6.

- _____. Late Beethoven: Music, Thought, Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 0-520-23746-3.

- Stanley, Glenn, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-58074-9 (hc), ISBN 0-521-58934-7 (pb).

- Thayer, A. W., rev and ed. Elliot Forbes. Thayer's Life of Beethoven. (2 vols.) Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09103-X

External links

- General reference

- Beethoven-Haus Bonn. Official website of Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, Germany. Links to extensive studio and digital archive, library holdings, the Beethoven-Haus Museum (including "internet exhibitions" and "virtual visits"), the Beethoven-Archiv research center, and information on Beethoven publications of interest to the specialist and general reader. Extensive collection of Beethoven's compositions and written documents, with sound samples and a digital reconstruction of his last house in Vienna.

- Raptus Association for Music Appreciation site on Beethoven

- One Stop Beethoven Resource - articles and facts about Beethoven from Aaron Green, guide to Classical Music at About.com.

- Analysis of the music and life of Beethoven on the All About Ludwig van Beethoven Page.

- The Beethoven Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61: Some Twentieth-Century Viewpoints

- Beethoven’s Personality and Music: The Introverted Romantic

- Keeping Score: Beethoven Symphony No. 3 multimedia website Rich multimedia website that explores the history and creation of Beethoven's Eroica Symphony. Presented by Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony

- Lists of Works

- University of Quebec In French. Contains links to the works arranged according to various criteria, and to a concordance of the various catalogues.

- Scores

- Beethoven Piano Sheet Music (out of copyright)

- Free scores by Ludwig van Beethoven in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Beethoven at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Works by Ludwig van Beethoven at Project Gutenberg, the oldest producer of public domain ebooks.

- Template:IckingArchive

- Recordings

- Musopen.com: Free Public Domain MP3 Files

- MP3 Creative Commons recordings from Magnatune

- Beethoven's Nine, The Philadelphia Orchestra performs all nine symphonies for NPR's Performance Today

- Piano Society — Beethoven. Many free recordings, articles and biography.

- Kunst der Fuge: hundreds of MIDI files

- The Unheard Beethoven - MIDI files of hundreds of Beethoven compositions never recorded and many that have never been published.

- Beethoven cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Ludwig van Beethoven discography at MusicBrainz, a collection of information about commercial recordings.

- Recording of the Ninth Symphony, with Maximianno Cobra directing the Europa Philharmonia Budapest Orchestra & Choir.

- Recording of the piano sonata opus 110, with extensive analysis

- Recording of the Quartets for Strings

- Recording of the Moonlight Sonata

- Specific topics

- Beethoven manuscripts at the British Library

- Contemporary reviews of Beethoven's works

- Pictures of "Beethoven in Vienna and Baden". In French.

- Beethoven's Hair - trace the journey of Beethoven's Hair.

- Für Elise - and other Beethoven resources.

- The Guevara Lock of Beethoven's Hair, from The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies.

- Hair analysis says Beethoven died of lead poisoning. CBC News, 18 October 2000.

- The Beethoven Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61: Some Twentieth-Century Viewpoints

- Related topics

- Beethoven's last apartment in Vienna, digitally reconstructed 2004, on Multimedia CD-ROM edited by Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Italic text

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Classical era composers

- Romantic composers

- German composers

- Opera composers

- Viennese composers

- German classical pianists

- The Enlightenment

- People with absolute pitch

- Suspected Freemasons

- Walhalla enshrinees

- Deaf people

- People from Bonn

- People buried at the Zentralfriedhof

- 1770 births

- 1827 deaths