Dahlonega, Georgia

Dahlonega, Georgia | |

|---|---|

City | |

Historic Lumpkin County Courthouse, which now houses the Dahlonega Gold Museum Historic Site | |

| Nickname: Gold City | |

Location in Lumpkin County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 34°32′N 83°59′W / 34.533°N 83.983°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Lumpkin |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sam Norton |

| • City Manager | Dan Halen |

| Area | |

• Total | 8.85 sq mi (22.93 km2) |

| • Land | 8.80 sq mi (22.79 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.14 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,450 ft (442 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

• Total | 5,242 |

• Estimate (2019)[2] | 7,294 |

| • Density | 829.05/sq mi (320.09/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 30533, 30597 |

| Area code | 706 |

| FIPS code | 13-21240[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0355420[4] |

| Website | dahlonega-ga |

The city of Dahlonega (/dəˈlɒnɪɡə/) is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States.[5] As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242,[6] and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.[7]

Dahlonega is located at the north end of Georgia 400, a freeway which connects Dahlonega to Atlanta. It was named as one of the best places to retire by the publication Real Estate Scorecard.[8]

Dahlonega was the site of the second discovery of gold in Georgia in 1828 (Villa Rica was first in 1826)[9] and only the second major gold rush in the United States. The Dahlonega Gold Museum Historic Site stands in the middle of the town square, housed in the 1836 Lumpkin County Courthouse. From its steps in 1849, Dahlonega Mint assayer Dr. M. F. Stephenson tried to persuade miners to stay in Dahlonega instead of joining the California Gold Rush, saying, "There's millions in it," often misquoted as "There's gold in them thar hills."[10][11]

Dahlonega is home to the oldest campus of the University of North Georgia, formerly North Georgia Agricultural College, then North Georgia College, then North Georgia College and State University.

History

Gold rush

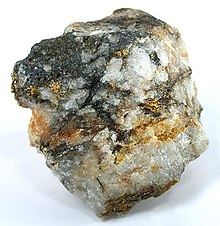

In the 1820s, Dahlonega was the site of the Georgia Gold Rush, the second significant gold rush in the United States, and became a boomtown.[12]

George Featherstonhough, an English geologist who visited the town in 1837, observed that the courthouse, designed by Ephriam Clayton,[13] was built upon a broad expanse of hornblende slate "and that the soil of the public square was impregnated with small specks of gold."[14] The courthouse building was paid for in part with gold bullion. It was made of bricks likely made locally, although possibly transported from Augusta. The foundation stone and timber were obtained locally.[13]

The spelling of the Cherokee word Da-lo-ni-ge-i was disputed by early correspondents; Featherstonhough, for example, wrote it as "Tahlonekay". The proper pronunciation of Dahlonega is (Dah-loe-nee-gee or Dah-lone-gay) in the Western Dialect of the Cherokee language. Da-lo-ni-ge'i does not mean gold but it simply means, Yellow. [15]

Since 1977, Cherokee descendants of Rachel Sabra Martin (1/4th Cherokee), organized as a tribe and are enrolled as members and have been recognized by the state as the Georgia Tribe of Eastern Cherokee. Dahlonega, Georgia, also has Native Americans who descend from historical Native American families, who migrated to the Oconaluftee Cherokees of North Carolina (Eastern Band Cherokee Indians of North Carolina) and to the Former Cherokee Nation. These Native Americans originated from Native American tribes from the Piedmont region, Eastern region of North Carolina and as well as regions of Virginia and South Carolina. These families became active citizens of the Oconaluftee Cherokees and the Former Cherokee Nation. When the Cherokee Rolls came out these Native Americans were not enrolled because they were not Cherokee by blood, yet they were Cherokee by culture, traditions and by language. Some of these Native Americans were forced on the 1838-39 Trail of Tears with the Cherokee Nation. Today, a handful of their descendants remain, who are scattered throughout the 30+ counties of North Georgia and are known as the SBOGAI – a traditional society and band.

A few surnames of the original Native American families of Dahlonega, Lumpkin County, Georgia: Defore, Stargel, Holloway, Chambers, Dover, Bird, Chattin, Walker, Davis, Whitmire, Whitmore, Dix, Martin, Woody, Worley, Palmour, Helton, Seabolt, Fields, Mills, Corn, Ralston, Postell and many more.

Today, in Dahlonega, Georgia, the Cherokee language is spoken by several Cherokee by blood and Adoptee Cherokee individuals. Several members of the Chambers, Dover, Stargel, Dix, Martin and Seabolt families still speak the Cherokee language (Western and Eastern dialects).

[16]

Illegal mining

Numerous gold mines were illegally developed in the area. White miners, entering illegally into the Cherokee Nation lands, came into conflict with the Cherokee, whose territory they had trespassed. The Cherokee Nation had their own gold mines which the United States Government tried to buy, but Principal Chief John Ross rejected their offer. Gold was mined by Cherokees and other Native Americans in the area before and after the Cherokee Removal of 1838-39. The Cherokee lands were defined by the treaty between the federal government and the Cherokee Nation in the Treaty of Washington (1819). The miners raised political pressure against the Cherokee because they wanted to get the gold. The federal government forced the Native Americans west of the Mississippi River to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears during Indian removal. Dahlonega was founded two years before the Treaty of New Echota (1835), which made its founding a violation of the Treaty of Washington of 1819.[17][18]

Naming the city

The city was named "Talonega" by the Georgia General Assembly on December 21, 1833.[20] The name was changed from Talonega by the Georgia General Assembly on December 25, 1837 to "Dahlonega",[20] from the Cherokee-language word Dalonige, meaning "yellow" or "gold".[19][21] The city is 5 miles (8 km) northeast of Auraria; each claims to be the site of the first discovery of gold. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (7th Vice President of the United States) owned the Calhoun Mine, just south of the city square.

Coin minting

The United States Mint built a branch mint there, which it operated from 1838 to 1861. The Dahlonega Mint, like the one established in 1838 in Charlotte, North Carolina, only minted gold coins, in denominations of $1.00, $2.50 (quarter eagle), $3.00 (1854 only) and $5.00 (half eagle). It was cost-effective in consideration of the economics, time, and risk of shipping gold to the main mint in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Dahlonega Mint was a small operation, usually accounting for only a small fraction of the gold coinage minted annually in the US.

The government decided against re-opening the facility after the Civil War. By then, the U.S. government had established a mint in San Francisco. Given the large amount of gold discovered in California from the late 1840s on, that one handled the national needs of gold minting.

As a result, surviving Dahlonega coinage is today highly prized in American numismatics. The mint building burned in 1878. North Georgia College built Price Memorial Hall on its foundation.[22] The building has a gold-leaf steeple to refer to the history of the site.

Wine and tourism

In recent years, Dahlonega and Lumpkin County have been recognized as "the heart of the North Georgia Wine Country".[citation needed] The county features multiple vineyards and five licensed wineries that attract many tourists.[citation needed]

The historic Dahlonega Square is a popular destination, with gift shops, restaurants, art galleries and studios, and wine-tasting rooms. In 2015, Senator Steve Gooch introduced Georgia Senate Resolution 125 officially recognizing Lumpkin County as the Wine Tasting Room Capital of Georgia.

The city's local festivals draw many visitors. "Bear on the Square", an annual three-day festival held the third weekend in April, marks the day that a black bear wandered onto the square. It features bluegrass and old-time music. "Gold Rush Days", an annual two-day event the third weekend in October, attracts over 200,000 people.[23]

Dahlonega is home to the Holly Theatre.

Historical marker

Located at 384 Mountain Drive, WPA Historical Marker 19 B-7 explains:

This court house, built in 1836, replaced the small structure used since the establishment of Lumpkin County in 1832. The town was named Dahlonega in October, 1833, for the Cherokee word Talonega meaning "golden."

From its steps in 1849, Dr. M.F. Stephenson, assayer at the Mint, attempted to dissuade Georgia miners from leaving to join the California Gold Rush. His oration gave rise to the sayings: "There's millions in it," and "Thar's gold in them thar hills."[24]

Geography

Dahlonega is located in central Lumpkin County at 34°32′N 83°59′W / 34.533°N 83.983°W (34.5305, −83.9847).[25] U.S. Route 19 passes through the east side of the city, leading north 34 miles (55 km) to Blairsville and south 65 miles (105 km) to Atlanta. Georgia State Route 400, a freeway which runs concurrently with US-19 to Atlanta, has its northern terminus 5 miles (8 km) south of the center of Dahlonega. State Routes 9 and 52 run concurrently around the south side of Dahlonega, joining US 19 on the southeast side. State Route 9 leads southwest 14 miles (23 km) to Dawsonville, while State Route 52 leads west 18 miles (29 km) to Amicalola Falls State Park. To the east State Route 52 leads 16 miles (26 km) to Clermont.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.8 square miles (22.9 km2), of which 0.05 square miles (0.14 km2), or 0.60%, are water.[26] The city is centered on a low ridge, with the west side draining to Cane Creek and the east side to Yahoola Creek. Both creeks flow south to the Chestatee River, part of the Chattahoochee River watershed. 1,720-foot (520 m) Crown Mountain is in the southern part of the city.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 671 | — | |

| 1850 | 735 | 9.5% | |

| 1870 | 471 | — | |

| 1880 | 602 | 27.8% | |

| 1890 | 896 | 48.8% | |

| 1900 | 1,255 | 40.1% | |

| 1910 | 829 | −33.9% | |

| 1920 | 690 | −16.8% | |

| 1930 | 905 | 31.2% | |

| 1940 | 1,294 | 43.0% | |

| 1950 | 2,152 | 66.3% | |

| 1960 | 2,604 | 21.0% | |

| 1970 | 2,658 | 2.1% | |

| 1980 | 2,844 | 7.0% | |

| 1990 | 3,086 | 8.5% | |

| 2000 | 3,638 | 17.9% | |

| 2010 | 5,242 | 44.1% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 7,294 | [2] | 39.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 5,242 people and 2,392 households. The population density was 568.1 people per square mile (219.5/km2). There were 1,181 housing units at an average density of 184.4 per square mile (71.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.3% White, 3.1% African American, 0.04% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 2.0% from other races, and 1.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.0% of the population.

There were 1,060 households, out of which 23.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.1% were married couples living together, 9.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.4% were non-families. 31.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.96.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 13.5% under the age of 18, 42.9% from 18 to 24, 19.0% from 25 to 44, 13.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females, there were 73.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 69.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,636, and the median income for a family was $44,904. Males had a median income of $30,500 versus $22,917 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,572. About 11.4% of families and 24.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.4% of those under age 18 and 13.8% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Lumpkin County School District

The Lumpkin County School District holds pre-school to grade twelve, and consists of three elementary schools, a middle school, and a high school.[28] The district has 215 full-time teachers and over 3,511 students.[29]

- Lumpkin County Elementary School

- Long Branch Elementary School

- Blackburn Elementary School

- Lumpkin County Middle School

- Lumpkin County High School

Higher education

Dahlonega is home to University of North Georgia (formerly named North Georgia College and State University), North Georgia College and North Georgia Agricultural College, the Senior Military College of Georgia and the second oldest public university in the State of Georgia. The University of North Georgia is one of six senior military colleges (along with the Public Campuses of Texas A&M University, the Citadel, the Virginia Military Institute and Virginia Tech, and the Private Campus of Norwich University). The campus' administration building, Price Memorial Hall, is topped with a spire covered with gold leaf from the town. The rotunda dome of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta is also covered with Dahlonega gold.

Other educational facilities

- Wahsega 4-H Center, an environmental education center and summer camp owned by the University of Georgia and administered through the UGA Cooperative Extension Service Georgia 4-H program

- Camp Glisson, a year-round retreat camp owned by the North Georgia Conference of the United Methodist Church

Residents

- Sara Christian, NASCAR's first female driver [citation needed]

- Steve Gooch, Georgia state senator and Majority Whip

- Dallas Kinney, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer

- Guy A. J. LaBoa, lieutenant general in the United States Army who commanded the 4th Infantry Division and First United States Army[30][31]

In popular culture

Corey Smith has a song titled "Dahlonega", in reference to the town and its landmarks, on his album While the Gettin' Is Good. The album was released on June 23, 2015.

Country music recording artist Ashley McBryde directly references the town in her debut single "A Little Dive Bar in Dahlonega", which was released in October 2017.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Dahlonega is twinned with:

References

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1), Dahlonega city, Georgia". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "Dahlonega, Georgia | Best Cities and Places to Live".

- ^ "First gold rush was in Villa Rica".

- ^ "Millions - Lumpkin County Historical Society".

- ^ ""Thar's Gold in Them Thar Hills": Gold and Gold Mining in Georgia, 1830s-1940s".

- ^ Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-915430-00-0.

- ^ a b Head, Sylvia Gailey; Etheridge, Elizabeth W. (2000). The Neighborhood Mint: Dahlonega in the Age of Jackson. Gold Rush Gallery, Alpharetta, Georgia. ISBN 978-0967976907.

- ^ Featherstonhough, George W. A Canoe Voyage Up the Minnay Sotor, 2 vols., London, 1847. Cited by Head, Sylvia and Etheridge, Elizabeth W.: The Neighborhood Mint: Dahlonega in the Age of Jackson, Gold Rush Gallery, Alpharetta, Georgia, 1986. (Quotation from Head and Etheridge.)

- ^ Coulter, E. Merton. Auraria, Athens, Georgia, 1956, pp. 99-100. (Cited by Head and Etheridge.)

- ^ Silavent, Joshua (February 21, 2016). "Fight over Cherokee blood line could be nearing resolution". Gainesville Times. Retrieved February 18, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ James Loewen, (1996).

- ^ "History - 1819 Treaty of Washington - GeorgiaInfo".

- ^ a b "English/Cherokee Dictionary". Retrieved April 17, 2012.(registration required)

- ^ a b Acts passed by the General Assembly, by J. Johnston, 1838

- ^ "The Names Stayed". Calhoun Times and Gordon County News. August 29, 1990. p. 64. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ Price Memorial Building State Historical Marker Archived September 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (accessed October 27, 2006)

- ^ Dahlonega Jaycees

- ^ Georgia Historical Markers Archived 12 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 27 October 2006)

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Gazetteer Files: 2019: Places: Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Georgia Board of Education[permanent dead link], Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ School Stats, Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ Stanford, Ken (March 3, 2004). "McCullough elected Dahlonega mayor". WDUN (AM). Gainesville, GA.

- ^ Bates, Diane (August 1, 2012). "Politics in Lumpkin County". Dahlonega and Beyond. Dahlonega, GA. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "Myślenice - Miasta partnerskie" [Myślenice - Partnership Cities] (in Polish). Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

Further reading

- "Gold-Mining in Georgia." Harper's New Monthly Magazine 59, Issue 352 (September 1879): 517–519. Available here

- I Remember Dahlonega: Memories of Growing Up in Lumpkin County, by Anne Dismukes Amerson (Chestatee Publishing: 1993)

- Williams, David (1993). The Georgia Gold Rush: Twenty-Niners, Cherokees, and Gold Fever. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-052-9.

- Williams, David, "'Such Excitement You Never Saw': Gold Mining in Nineteenth-Century Georgia", The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 76, No. 3 (Fall 1992), pp. 695–707, Georgia Historical Society. Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40582597